cardiovascular disease

Immune Resilience is Key to a Long and Healthy Life

Posted on by Lawrence Tabak, D.D.S., Ph.D.

Do you feel as if you or perhaps your family members are constantly coming down with illnesses that drag on longer than they should? Or, maybe you’re one of those lucky people who rarely becomes ill and, if you do, recovers faster than others.

It’s clear that some people generally are more susceptible to infectious illnesses, while others manage to stay healthier or bounce back more quickly, sometimes even into old age. Why is this? A new study from an NIH-supported team has an intriguing answer [1]. The difference, they suggest, may be explained in part by a new measure of immunity they call immune resilience—the ability of the immune system to rapidly launch attacks that defend effectively against infectious invaders and respond appropriately to other types of inflammatory stressors, including aging or other health conditions, and then quickly recover, while keeping potentially damaging inflammation under wraps.

The findings in the journal Nature Communications come from an international team led by Sunil Ahuja, University of Texas Health Science Center and the Department of Veterans Affairs Center for Personalized Medicine, both in San Antonio. To understand the role of immune resilience and its effect on longevity and health outcomes, the researchers looked at multiple other studies including healthy individuals and those with a range of health conditions that challenged their immune systems.

By looking at multiple studies in varied infectious and other contexts, they hoped to find clues as to why some people remain healthier even in the face of varied inflammatory stressors, ranging from mild to more severe. But to understand how immune resilience influences health outcomes, they first needed a way to measure or grade this immune attribute.

The researchers developed two methods for measuring immune resilience. The first metric, a laboratory test called immune health grades (IHGs), is a four-tier grading system that calculates the balance between infection-fighting CD8+ and CD4+ T-cells. IHG-I denotes the best balance tracking the highest level of resilience, and IHG-IV denotes the worst balance tracking the lowest level of immune resilience. An imbalance between the levels of these T cell types is observed in many people as they age, when they get sick, and in people with autoimmune diseases and other conditions.

The researchers also developed a second metric that looks for two patterns of expression of a select set of genes. One pattern associated with survival and the other with death. The survival-associated pattern is primarily related to immune competence, or the immune system’s ability to function swiftly and restore activities that encourage disease resistance. The mortality-associated genes are closely related to inflammation, a process through which the immune system eliminates pathogens and begins the healing process but that also underlies many disease states.

Their studies have shown that high expression of the survival-associated genes and lower expression of mortality-associated genes indicate optimal immune resilience, correlating with a longer lifespan. The opposite pattern indicates poor resilience and a greater risk of premature death. When both sets of genes are either low or high at the same time, immune resilience and mortality risks are more moderate.

In the newly reported study initiated in 2014, Ahuja and his colleagues set out to assess immune resilience in a collection of about 48,500 people, with or without various acute, repetitive, or chronic challenges to their immune systems. In an earlier study, the researchers showed that this novel way to measure immune status and resilience predicted hospitalization and mortality during acute COVID-19 across a wide age spectrum [2].

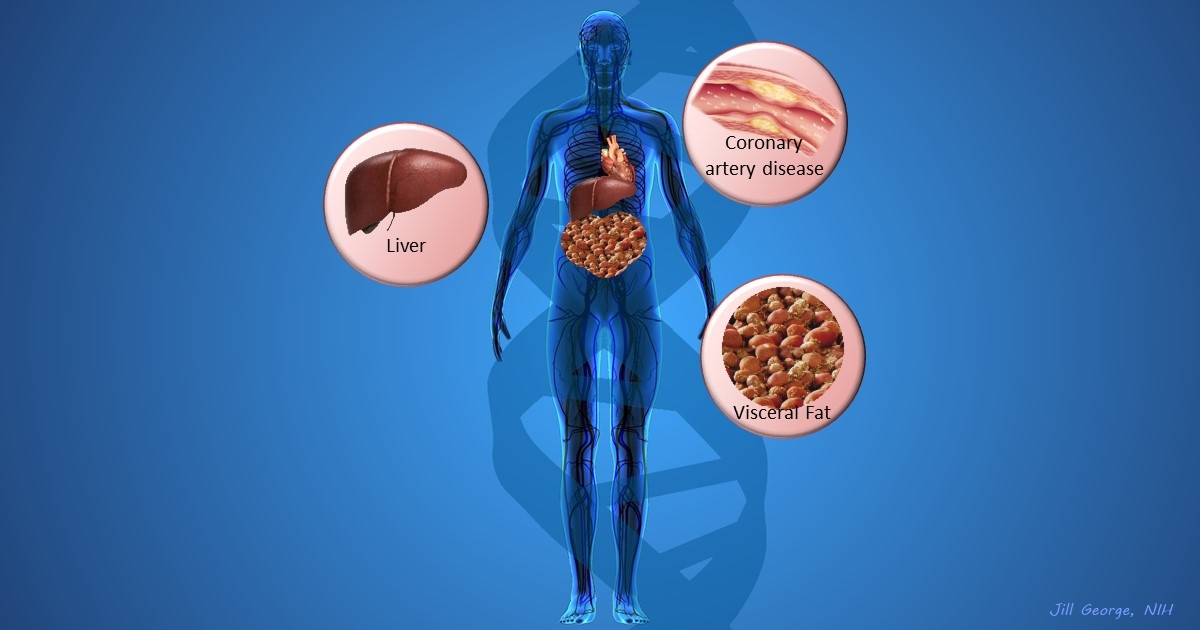

The investigators have analyzed stored blood samples and publicly available data representing people, many of whom were healthy volunteers, who had enrolled in different studies conducted in Africa, Europe, and North America. Volunteers ranged in age from 9 to 103 years. They also evaluated participants in the Framingham Heart Study, a long-term effort to identify common factors and characteristics that contribute to cardiovascular disease.

To examine people with a wide range of health challenges and associated stresses on their immune systems, the team also included participants who had influenza or COVID-19, and people living with HIV. They also included kidney transplant recipients, people with lifestyle factors that put them at high risk for sexually transmitted infections, and people who’d had sepsis, a condition in which the body has an extreme and life-threatening response following an infection.

The question in all these contexts was the same: How well did the two metrics of immune resilience predict an individual’s health outcomes and lifespan? The short answer is that immune resilience, longevity, and better health outcomes tracked together well. Those with metrics indicating optimal immune resilience generally had better health outcomes and lived longer than those who had lower scores on the immunity grading scale. Indeed, those with optimal immune resilience were more likely to:

- Live longer,

- Resist HIV infection or the progression from HIV to AIDS,

- Resist symptomatic influenza,

- Resist a recurrence of skin cancer after a kidney transplant,

- Survive COVID-19, and

- Survive sepsis.

The study also revealed other interesting findings. While immune resilience generally declines with age, some people maintain higher levels of immune resilience as they get older for reasons that aren’t yet known, according to the researchers. Some people also maintain higher levels of immune resilience despite the presence of inflammatory stress to their immune systems such as during HIV infection or acute COVID-19. People of all ages can show high or low immune resilience. The study also found that higher immune resilience is more common in females than it is in males.

The findings suggest that there is a lot more to learn about why people differ in their ability to preserve optimal immune resilience. With further research, it may be possible to develop treatments or other methods to encourage or restore immune resilience as a way of improving general health, according to the study team.

The researchers suggest it’s possible that one day checkups of a person’s immune resilience could help us to understand and predict an individual’s health status and risk for a wide range of health conditions. It could also help to identify those individuals who may be at a higher risk of poor outcomes when they do get sick and may need more aggressive treatment. Researchers may also consider immune resilience when designing vaccine clinical trials.

A more thorough understanding of immune resilience and discovery of ways to improve it may help to address important health disparities linked to differences in race, ethnicity, geography, and other factors. We know that healthy eating, exercising, and taking precautions to avoid getting sick foster good health and longevity; in the future, perhaps we’ll also consider how our immune resilience measures up and take steps to achieve or maintain a healthier, more balanced, immunity status.

References:

[1] Immune resilience despite inflammatory stress promotes longevity and favorable health outcomes including resistance to infection. Ahuja SK, Manoharan MS, Lee GC, McKinnon LR, Meunier JA, Steri M, Harper N, Fiorillo E, Smith AM, Restrepo MI, Branum AP, Bottomley MJ, Orrù V, Jimenez F, Carrillo A, Pandranki L, Winter CA, Winter LA, Gaitan AA, Moreira AG, Walter EA, Silvestri G, King CL, Zheng YT, Zheng HY, Kimani J, Blake Ball T, Plummer FA, Fowke KR, Harden PN, Wood KJ, Ferris MT, Lund JM, Heise MT, Garrett N, Canady KR, Abdool Karim SS, Little SJ, Gianella S, Smith DM, Letendre S, Richman DD, Cucca F, Trinh H, Sanchez-Reilly S, Hecht JM, Cadena Zuluaga JA, Anzueto A, Pugh JA; South Texas Veterans Health Care System COVID-19 team; Agan BK, Root-Bernstein R, Clark RA, Okulicz JF, He W. Nat Commun. 2023 Jun 13;14(1):3286. doi: 10.1038/s41467-023-38238-6. PMID: 37311745.

[2] Immunologic resilience and COVID-19 survival advantage. Lee GC, Restrepo MI, Harper N, Manoharan MS, Smith AM, Meunier JA, Sanchez-Reilly S, Ehsan A, Branum AP, Winter C, Winter L, Jimenez F, Pandranki L, Carrillo A, Perez GL, Anzueto A, Trinh H, Lee M, Hecht JM, Martinez-Vargas C, Sehgal RT, Cadena J, Walter EA, Oakman K, Benavides R, Pugh JA; South Texas Veterans Health Care System COVID-19 Team; Letendre S, Steri M, Orrù V, Fiorillo E, Cucca F, Moreira AG, Zhang N, Leadbetter E, Agan BK, Richman DD, He W, Clark RA, Okulicz JF, Ahuja SK. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2021 Nov;148(5):1176-1191. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2021.08.021. Epub 2021 Sep 8. PMID: 34508765; PMCID: PMC8425719.

Links:

COVID-19 Research (NIH)

HIV Info (NIH)

Sepsis (National Institute of General Medical Sciences/NIH)

Sunil Ahuja (University of Texas Health Science Center, San Antonio)

Framingham Heart Study (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute/NIH)

“A Secret to Health and Long Life? Immune Resilience, NIAID Grantees Report,” NIAID Now Blog, June 13, 2023

NIH Support: National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases; National Institute on Aging; National Institute of Mental Health; National Institute of General Medical Sciences; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute

Aging Research: Blood Proteins Show Your Age

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

How can you tell how old someone is? Of course, you could scan their driver’s license or look for signs of facial wrinkles and gray hair. But, as researchers just found in a new study, you also could get pretty close to the answer by doing a blood test.

That may seem surprising. But in a recent study in Nature Medicine, an NIH-funded research team was able to gauge a person’s age quite reliably by analyzing a blood sample for levels of a few hundred proteins. The results offer important new insights into what happens as we age. For example, the team suggests that the biological aging process isn’t steady and appears to accelerate periodically—with the greatest bursts coming, on average, around ages 34, 60, and 78.

These findings indicate that it may be possible one day to devise a blood test to identify individuals who are aging faster biologically than others. Such folks might be at risk earlier in life for cardiovascular problems, Alzheimer’s disease, osteoarthritis, and other age-related health issues.

What’s more, this work raises hope for interventions that may slow down the “proteomic clock” and perhaps help to keep people biologically younger than their chronological age. Such a scenario might sound like pure fantasy, but this same group of researchers showed a few years ago that it’s indeed possible to rejuvenate an older mouse by infusing blood from a much younger mouse.

Those and other earlier findings from the lab of Tony Wyss-Coray, Stanford School of Medicine, Palo Alto, CA, raised the tantalizing possibility that certain substances in young blood can revitalize the aging brain and other parts of the body. In search of additional clues in the new study, the Wyss-Coray team tracked how the protein composition of blood changes as people age.

To find those clues, they isolated plasma from more than 4,200 healthy individuals between ages 18 and 95. The researchers then used data from more than half of the participants to assemble a “proteomic clock” of aging. Within certain limits, the clock could accurately predict the chronological age of the study’s remaining 1,446 participants. The best predictions relied on just 373 of the clock’s almost 3,000 proteins.

As further validation, the clock also reliably predicted the correct chronological age of four groups of people not in the study. Interestingly, it was possible to make a decent age prediction based on just nine of the clock’s most informative proteins.

The findings show that telltale proteomic changes arise with age, and they likely have important and as-yet unknown health implications. After all, those proteins found circulating in the bloodstream come not just from blood cells but also from cells throughout the body. Intriguingly, the researchers report that people who appeared biologically younger than their actual chronological age based on their blood proteins also performed better on cognitive and physical tests.

Most of us view aging as a gradual, linear process. However, the protein evidence suggests that, biologically, aging follows a more complex pattern. Some proteins did gradually tick up or down over time in an almost linear fashion. But the levels of many other proteins rose or fell more markedly over time. For instance, one neural protein in the blood stayed constant until around age 60, when its levels spiked. Why that is so remains to be determined.

As noted, the researchers found evidence that the aging process includes a series of three bursts. Wyss-Coray said he found it especially interesting that the first burst happens in early mid-life, around age 34, well before common signs of aging and its associated health problems would manifest.

It’s also well known that men and women age differently, and this study adds to that evidence. About two-thirds of the proteins that changed with age also differed between the sexes. However, because the effect of aging on the most important proteins of the clock is much stronger than the differences in gender, the proteomic clock still could accurately predict the ages in all people.

Overall, the findings show that protein substances in blood can serve as a useful measure of a person’s chronological and biological age and—together with Wyss-Coray’s earlier studies—that substances in blood may play an active role in the aging process. Wyss-Coray reports that his team continues to dig deeper into its data, hoping to learn more about the origins of particular proteins in the bloodstream, what they mean for our health, and how to potentially turn back the proteomic clock.

Reference:

[1] Undulating changes in human plasma proteome profiles across the lifespan. Lehallier B, Gate D, Schaum N, Nanasi T, Lee SE, Yousef H, Moran Losada P, Berdnik D, Keller A, Verghese J, Sathyan S, Franceschi C, Milman S, Barzilai N, Wyss-Coray T. Nat Med. 2019 Dec;25(12):1843-1850.

Links:

What Do We Know About Healthy Aging? (National Institute on Aging/NIH)

Cognitive Health (NIA)

Wyss-Coray Lab (Stanford University, Palo Alto, CA)

NIH Support: National Institute on Aging

Study Finds No Benefit for Dietary Supplements

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

More than half of U.S. adults take dietary supplements [1]. I don’t, but some of my family members do. But does popping all of these vitamins, minerals, and other substances really lead to a longer, healthier life? A new nationwide study suggests it doesn’t.

Based on an analysis of survey data gathered from more than 27,000 people over a six-year period, the NIH-funded study found that individuals who reported taking dietary supplements had about the same risk of dying as those who got their nutrients through food. What’s more, the mortality benefits associated with adequate intake of vitamin A, vitamin K, magnesium, zinc, and copper were limited to food consumption.

The study, published in the Annals of Internal Medicine, also uncovered some evidence suggesting that certain supplements might even be harmful to health when taken in excess [2]. For instance, people who took more than 1,000 milligrams of supplemental calcium per day were more likely to die of cancer than those who didn’t.

The researchers, led by Fang Fang Zhang, Tufts University, Boston, were intrigued that so many people take dietary supplements, despite questions about their health benefits. While the overall evidence had suggested no benefits or harms, results of a limited number of studies had suggested that high doses of certain supplements could be harmful in some cases.

To take a broader look, Zhang’s team took advantage of survey data from tens of thousands of U.S. adults, age 20 or older, who had participated in six annual cycles of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) between 1999-2000 and 2009-2010. NHANES participants were asked whether they’d used any dietary supplements in the previous 30 days. Those who answered yes were then asked to provide further details on the specific product(s) and how long and often they’d taken them.

Just over half of participants reported use of dietary supplements in the previous 30 days. Nearly 40 percent reported use of multivitamins containing three or more vitamins.

Nutrient intake from foods was also assessed. Each year, the study’s participants were asked to recall what they’d eaten over the last 24 hours. The researchers then used that information to calculate participants’ nutrient intake from food. Those calculations indicated that more than half of the study’s participants had inadequate intake of vitamins D, E, and K, as well as choline and potassium.

Over the course of the study, more than 3,600 of the study’s participants died. Those deaths included 945 attributed to cardiovascular disease and 805 attributed to cancer. The next step was to look for any association between the nutrient intake and the mortality data.

The researchers found the use of dietary supplements had no influence on mortality. People with adequate intake of vitamin A, vitamin K, magnesium, zinc, and copper were less likely to die. However, that relationship only held for nutrient intake from food consumption.

People who reported taking more than 1,000 milligrams of calcium per day were more likely to die of cancer. There was also evidence that people who took supplemental vitamin D at a dose exceeding 10 micrograms (400 IU) per day without a vitamin D deficiency were more likely to die from cancer.

It’s worth noting that the researchers did initially see an association between the use of dietary supplements and a lower risk of death due to all causes. However, those associations vanished when they accounted for other potentially confounding factors.

For example, study participants who reported taking dietary supplements generally had a higher level of education and income. They also tended to enjoy a healthier lifestyle. They ate more nutritious food, were less likely to smoke or drink alcohol, and exercised more. So, it appears that people who take dietary supplements are likely to live a longer and healthier life for reasons that are unrelated to their supplement use.

While the study has some limitations, including the difficulty in distinguishing association from causation, and a reliance on self-reported data, its findings suggest that the regular use of dietary supplements should not be recommended for the general U.S. population. Of course, this doesn’t rule out the possibility that certain subgroups of people, including perhaps those following certain special diets or with known nutritional deficiencies, may benefit.

These findings serve up a reminder that dietary supplements are no substitute for other evidence-based approaches to health maintenance and eating nutritious food. Right now, the best way to live a long and healthy life is to follow the good advice offered by the rigorous and highly objective reviews provided by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force [3]. Those tend to align with what I hope your parents offered: eat a balanced diet, including plenty of fruits, veggies, and healthy sources of calcium and protein. Don’t smoke. Use alcohol in moderation. Avoid recreational drugs. Get plenty of exercise.

References:

[1] Trends in Dietary Supplement Use Among US Adults From 1999-2012. Kantor ED, Rehm CD, Du M, White E, Giovannucci EL. JAMA. 2016 Oct 11;316(14):1464-1474.

[2] Association among dietary supplement use, nutrient intake, and mortality among U.S. adults. Chen F, Du M, Blumberg JB, Ho Chui KK, Ruan M, Rogers G, Shan Z, Zeng L, Zhang. Ann Intern Med. 2019 Apr 9. [Epub ahead of print].

[3] Vitamin Supplementation to Prevent Cancer and CVD: Preventive Medication. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, February 2014.

Links:

Office of Dietary Supplements (NIH)

Healthy Eating Plan (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute/NIH)

National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta)

U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (Rockville, MD)

Fang Fang Zhang (Tufts University, Boston)

NIH Support: National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities

An Aspirin a Day for Older People Doesn’t Prolong Healthy Lifespan

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Credit: iStock/thodonal

Many older people who’ve survived a heart attack or stroke take low-dose aspirin every day to help prevent further cardiovascular problems [1]. There is compelling evidence that this works. But should perfectly healthy older folks follow suit?

Most of us would have guessed “yes”—but the answer appears to be “no” when you consider the latest scientific evidence. Recently, a large, international study of older people without a history of cardiovascular disease found that those who took a low-dose aspirin daily over more than 4 years weren’t any healthier than those who didn’t. What’s more, there were some unexpected indications that low-dose aspirin might even boost the risk of death.

Creative Minds: A New Mechanism for Epigenetics?

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

To learn more about how DNA and inheritance works, Keith Maggert has spent much of his nearly 30 years as a researcher studying what takes place not just within the DNA genome but also the subtle modifications of it. That’s where a stable of enzymes add chemical marks to DNA, turning individual genes on or off without changing their underlying sequence. What’s really intrigued Maggert is these “epigenetic” modifications are maintained through cell division and can even get passed down from parent to child over many generations. Like many researchers, he wants to know how it happens.

Maggert thinks there’s more to the story than scientists have realized. Now an associate professor at the University of Arizona College of Medicine, Tucson, he suspects that a prominent subcellular structure in the nucleus called the nucleolus also exerts powerful epigenetic effects. What’s different about the nucleolus, Maggert proposes, is it doesn’t affect genes one by one, a focal point of current epigenetic research. He thinks under some circumstances its epigenetic effects can activate many previously silenced, or “off” genes at once, sending cells and individuals on a different path toward health or disease.

Maggert has received a 2016 NIH Director’s Transformative Research Award to pursue this potentially new paradigm. If correct, it would transform current thinking in the field and provide an exciting new perspective to track epigenetics and its contributions to a wide range of human diseases, including cancer, cardiovascular disease, and neurodegenerative disorders.

Study Finds No Safe Level of Smoking

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Thinkstock\Nastco

Many Americans who’ve smoked cigarettes have been successful in their efforts to quit. But there’s some bad news for those who’ve settled for just cutting back: new evidence shows there’s no safe amount of smoking. One cigarette a day, or even less than that, still poses significant risks to your health.

A study conducted by NIH researchers of more than 290,000 adults between the ages of 59 and 82 found that those who reported smoking less than one cigarette per day, on average, for most of their lives were nine times more likely to die from lung cancer than those who never smoked. The outlook was even worse for those who smoked between one and 10 cigarettes a day. Compared to never-smokers, they faced a 12 times greater risk of dying from lung cancer and 1½ times greater risk of dying of cardiovascular disease.

Next Page