genome

All of Us: Release of Nearly 100,000 Whole Genome Sequences Sets Stage for New Discoveries

Posted on by Joshua Denny, M.D., M.S., and Lawrence Tabak, D.D.S., Ph.D.

Nearly four years ago, NIH opened national enrollment for the All of Us Research Program. This historic program is building a vital research community within the United States of at least 1 million participant partners from all backgrounds. Its unifying goal is to advance precision medicine, an emerging form of health care tailored specifically to the individual, not the average patient as is now often the case. As part of this historic effort, many participants have offered DNA samples for whole genome sequencing, which provides information about almost all of an individual’s genetic makeup.

Earlier this month, the All of Us Research Program hit an important milestone. We released the first set of nearly 100,000 whole genome sequences from our participant partners. The sequences are stored in the All of Us Researcher Workbench, a powerful, cloud-based analytics platform that makes these data broadly accessible to registered researchers.

The All of Us Research Program and its many participant partners are leading the way toward more equitable representation in medical research. About half of this new genomic information comes from people who self-identify with a racial or ethnic minority group. That’s extremely important because, until now, over 90 percent of participants in large genomic studies were of European descent. This lack of diversity has had huge impacts—deepening health disparities and hindering scientific discovery from fully benefiting everyone.

The Researcher Workbench also contains information from many of the participants’ electronic health records, Fitbit devices, and survey responses. Another neat feature is that the platform links to data from the U.S. Census Bureau’s American Community Survey to provide more details about the communities where participants live.

This unique and comprehensive combination of data will be key in transforming our understanding of health and disease. For example, given the vast amount of data and diversity in the Researcher Workbench, new diseases are undoubtedly waiting to be uncovered and defined. Many new genetic variants are also waiting to be identified that may better predict disease risk and response to treatment.

To speed up the discovery process, these data are being made available, both widely and wisely. To protect participants’ privacy, the program has removed all direct identifiers from the data and upholds strict requirements for researchers seeking access. Already, more than 1,500 scientists across the United States have gained access to the Researcher Workbench through their institutions after completing training and agreeing to the program’s strict rules for responsible use. Some of these researchers are already making discoveries that promote precision medicine, such as finding ways to predict how to best to prevent vision loss in patients with glaucoma.

Beyond making genomic data available for research, All of Us participants have the opportunity to receive their personal DNA results, at no cost to them. So far, the program has offered genetic ancestry and trait results to more than 100,000 participants. Plans are underway to begin sharing health-related DNA results on hereditary disease risk and medication-gene interactions later this year.

This first release of genomic data is a huge milestone for the program and for health research more broadly, but it’s also just the start. The program’s genome centers continue to generate the genomic data and process about 5,000 additional participant DNA samples every week.

The ultimate goal is to gather health data from at least 1 million or more people living in the United States, and there’s plenty of time to join the effort. Whether you would like to contribute your own DNA and health information, engage in research, or support the All of Us Research Program as a partner, it’s easy to get involved. By taking part in this historic program, you can help to build a better and more equitable future for health research and precision medicine.

Note: Joshua Denny, M.D., M.S., is the Chief Executive Officer of NIH’s All of Us Research Program.

Links:

All of Us Research Program (NIH)

Join All of Us (NIH)

A New View of the 3D Genome

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

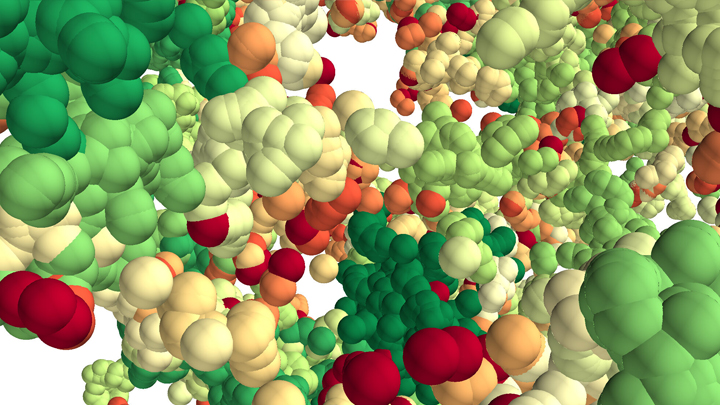

This lush panoply of color might stir up daydreams of getting away to explore a tropical rain forest. But what you see here is a new model that’s enabling researchers to explore something equally amazing: how a string of DNA that measures 6 feet long can be packed into the microscopic nucleus of a human cell. Fitting that much DNA in a nucleus is like fitting a thread the length of the Empire State building underneath your fingernail!

Scientists have known for a while that that the answer lies in how DNA is folded onto spool-like complexes called chromatin, but many details of the process still remain to be worked out. Recently, an NIH-funded team, led by Vadim Backman and Igal Szleifer, Northwestern University, Evanston, IL, developed this new model of chromatin folding by pairing sophisticated mathematical modeling and optical imaging.In a study published in the journal Science Advances [1], the team found that chromatin is folded into a variety of tree-like domains along a chromatin backbone, which they liken to an aggregation of trees growing from the forest floor. The colorful spheres you see above represent trees of varying sizes.

Earlier models of chromatin folding had suggested that DNA folds into regular and orderly fibers. In the new study, the Northwestern researchers used their own specially designed Partial Wave Spectroscopic microscope. This high-powered system, coupled with electron imaging, allowed them to peer deep inside living cells to “sense” real-time alterations in chromatin packing. What makes their new view on chromatin so interesting is it suggests our DNA is packaged in a way that’s much more disorderly and unpredictable than initially thought.

As Backman notes, it is reasonable to assume that a forest would be filled with trees of varying sizes and shapes. But you couldn’t predict the exact location of each tree or its particular size and configuration. The same appears to be true of these tree-like structures within chromatin. Their precise location and size vary, seemingly unpredictably, from cell to cell.

This apparently random DNA packing structure might seem surprising given chromatin’s importance in influencing the expression and function of our genes. But the researchers think such variability likely has its advantages.

Here’s the idea: If all of our cells responded to stressful conditions (such as heat or a toxic exposure) in exactly the same way and that way happened to be suboptimal, the whole tissue or organ might fail. But if differences in chromatin structure lead each cell to respond somewhat differently to the same stimulus, then some cells might be more likely to survive or even thrive under the stress. It’s a built-in way for cells to hedge their bets.

These new findings offer a fundamentally new three-dimensional view of the human genome. They might also inspire innovative strategies to understand and fight cancer, as well as other diseases. And, while most of us probably won’t be venturing off into the rain forest anytime soon, this work does give us all something to think about next time we’re enjoying the great outdoors in our own neck of the woods.

Reference:

[1] Physical and data structure of 3D genome. Huang K, Li Y, Shim AR, Virk RKA, Agrawal V, Eshein A, Nap RJ, Almassalha LM, Backman V, Szleifer I. Sci Adv. 2020 Jan 10;6(2):eaay4055.

Links:

Deoxyribonucleic Acid (DNA) (National Human Genome Research Institute/NIH)

4D Nucleome (Common Fund/NIH)

Vadim Backman (Northwestern University, Evanston, IL)

Igal Szleifer (Northwestern University, Evanston, IL)

NIH Support: National Cancer Institute

Genes, Blood Type Tied to Risk of Severe COVID-19

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Credit: National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, NIH

Many people who contract COVID-19 have only a mild illness, or sometimes no symptoms at all. But others develop respiratory failure that requires oxygen support or even a ventilator to help them recover [1]. It’s clear that this happens more often in men than in women, as well as in people who are older or who have chronic health conditions. But why does respiratory failure also sometimes occur in people who are young and seemingly healthy?

A new study suggests that part of the answer to this question may be found in the genes that each one of us carries [2]. While more research is needed to pinpoint the precise underlying genes and mechanisms responsible, a recent genome-wide association (GWAS) study, just published in the New England Journal of Medicine, finds that gene variants in two regions of the human genome are associated with severe COVID-19 and correspondingly carry a greater risk of COVID-19-related death.

The two stretches of DNA implicated as harboring risks for severe COVID-19 are known to carry some intriguing genes, including one that determines blood type and others that play various roles in the immune system. In fact, the findings suggest that people with blood type A face a 50 percent greater risk of needing oxygen support or a ventilator should they become infected with the novel coronavirus. In contrast, people with blood type O appear to have about a 50 percent reduced risk of severe COVID-19.

These new findings—the first to identify statistically significant susceptibility genes for the severity of COVID-19—come from a large research effort led by Andre Franke, a scientist at Christian-Albrecht-University, Kiel, Germany, along with Tom Karlsen, Oslo University Hospital Rikshospitalet, Norway. Their study included 1,980 people undergoing treatment for severe COVID-19 and respiratory failure at seven medical centers in Italy and Spain.

In search of gene variants that might play a role in the severe illness, the team analyzed patient genome data for more than 8.5 million so-called single-nucleotide polymorphisms, or SNPs. The vast majority of these single “letter” nucleotide substitutions found all across the genome are of no health significance, but they can help to pinpoint the locations of gene variants that turn up more often in association with particular traits or conditions—in this case, COVID-19-related respiratory failure. To find them, the researchers compared SNPs in people with severe COVID-19 to those in more than 1,200 healthy blood donors from the same population groups.

The analysis identified two places that turned up significantly more often in the individuals with severe COVID-19 than in the healthy folks. One of them is found on chromosome 3 and covers a cluster of six genes with potentially relevant functions. For instance, this portion of the genome encodes a transporter protein known to interact with angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ACE2), the surface receptor that allows the novel coronavirus that causes COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2, to bind to and infect human cells. It also encodes a collection of chemokine receptors, which play a role in the immune response in the airways of our lungs.

The other association signal popped up on chromosome 9, right over the area of the genome that determines blood type. Whether you are classified as an A, B, AB, or O blood type, depends on how your genes instruct your blood cells to produce (or not produce) a certain set of proteins. The researchers did find evidence suggesting a relationship between blood type and COVID-19 risk. They noted that this area also includes a genetic variant associated with increased levels of interleukin-6, which plays a role in inflammation and may have implications for COVID-19 as well.

These findings, completed in two months under very difficult clinical conditions, clearly warrant further study to understand the implications more fully. Indeed, Franke, Karlsen, and many of their colleagues are part of the COVID-19 Host Genetics Initiative, an ongoing international collaborative effort to learn the genetic determinants of COVID-19 susceptibility, severity, and outcomes. Some NIH research groups are taking part in the initiative, and they recently launched a study to look for informative gene variants in 5,000 COVID-19 patients in the United States and Canada.

The hope is that these and other findings yet to come will point the way to a more thorough understanding of the biology of COVID-19. They also suggest that a genetic test and a person’s blood type might provide useful tools for identifying those who may be at greater risk of serious illness.

References:

[1] Characteristics of and important lessons from the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: Summary of a report of 72 314 cases from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Wu Z, McGoogan JM, et. al. 2020 Feb 24. [published online ahead of print]

[2] Genomewide association study of severe Covid-19 with respiratory failure. Ellinghaus D, Degenhardt F, et. a. NEJM. June 17, 2020.

Links:

The COVID-19 Host Genetics Initiative

Andre Franke (Christian-Albrechts-University of Kiel, Germany)

Tom Karlsen (Oslo University Hospital Rikshospitalet, Norway)

Biomedical Research Highlighted in Science’s 2018 Breakthroughs

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

A Happy New Year to one and all! While many of us were busy wrapping presents, the journal Science announced its much-anticipated scientific breakthroughs of 2018. In case you missed the announcement [1], it was another banner year for the biomedical sciences.

The 2018 Breakthrough of the Year went to biomedical science and its ability to track the development of life—one cell at a time—in a variety of model organisms. This newfound ability opens opportunities to understand the biological basis of life more systematically than ever before. Among Science’s “runner-up” breakthroughs, more than half had strong ties to the biomedical sciences and NIH-supported research.

Sound intriguing? Let’s take a closer look at some of the amazing science conducted in 2018, starting with Science’s Breakthrough of the Year.

Development Cell by Cell: For millennia, biologists have wondered how a single cell develops into a complete multicellular organism, such as a frog or a mouse. But solving that mystery was almost impossible without the needed tools to study development systematically, one cell at a time. That’s finally started to change within the last decade. I’ve highlighted the emergence of some of these powerful tools on my blog and the interesting ways that they were being applied to study development.

Over the past few years, all of this technological progress has come to a head. Researchers, many of them NIH-supported, used sophisticated cell labeling techniques, nucleic acid sequencing, and computational strategies to isolate thousands of cells from developing organisms, sequence their genetic material, and determine their location within that developing organism.

In 2018 alone, groundbreaking single-cell analysis papers were published that sequentially tracked the 20-plus cell types that arise from a fertilized zebrafish egg, the early formation of organs in a frog, and even the creation of a new limb in the Axolotl salamander. This is just the start of amazing discoveries that will help to inform us of the steps, or sometimes missteps, within human development—and suggest the best ways to prevent the missteps. In fact, efforts are now underway to gain this detailed information in people, cell by cell, including the international Human Cell Atlas and the NIH-supported Human BioMolecular Atlas Program.

An RNA Drug Enters the Clinic: Twenty years ago, researchers Andrew Fire and Craig Mello showed that certain small, noncoding RNA molecules can selectively block genes in our cells from turning “on” through a process called RNA interference (RNAi). This work, for the which these NIH grantees received the 2006 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, soon sparked a wave of commercial interest in various noncoding RNA molecules for their potential to silence the expression of a disease-causing gene.

After much hard work, the first gene-silencing RNA drug finally came to market in 2018. It’s called Onpattro™ (patisiran), and the drug uses RNAi to treat the peripheral nerve disease that can afflict adults with a rare disease called hereditary transthyretin-mediated amyloidosis. This hard-won success may spark further development of this novel class of biopharmaceuticals to treat a variety of conditions, from cancer to cardiovascular disorders, with potentially greater precision.

Rapid Chemical Structure Determination: Last October, two research teams released papers almost simultaneously that described an incredibly fast new imaging technique to determine the structure of smaller organic chemical compounds, or “small molecules“ at atomic resolution. Small molecules are essential components of molecular biology, pharmacology, and drug development. In fact, most of our current medicines are small molecules.

News of these papers had many researchers buzzing, and I highlighted one of them on my blog. It described a technique called microcrystal electron diffraction, or MicroED. It enabled these NIH-supported researchers to take a powder form of small molecules (progesterone was one example) and generate high-resolution data on their chemical structures in less than a half-hour! The ease and speed of MicroED could revolutionize not only how researchers study various disease processes, but aid in pinpointing which of the vast number of small molecules can become successful therapeutics.

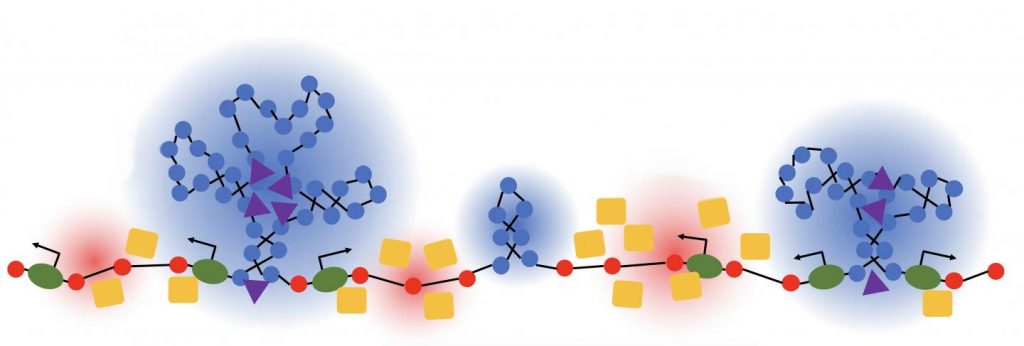

How Cells Marshal Their Contents: About a decade ago, researchers discovered that many proteins in our cells, especially when stressed, condense into circumscribed aqueous droplets. This so-called phase separation allows proteins to gather in higher concentrations and promote reactions with other proteins. The NIH soon began supporting several research teams in their groundbreaking efforts to explore the effects of phase separation on cell biology.

Over the past few years, work on phase separation has taken off. The research suggests that this phenomenon is critical in compartmentalizing chemical reactions within the cell without the need of partitioning membranes. In 2018 alone, several major papers were published, and the progress already has some suggesting that phase separation is not only a basic organizing principle of the cell, it’s one of the major recent breakthroughs in biology.

Forensic Genealogy Comes of Age: Last April, police in Sacramento, CA announced that they had arrested a suspect in the decades-long hunt for the notorious Golden State Killer. As exciting as the news was, doubly interesting was how they caught the accused killer. The police had the Golden Gate Killer’s DNA, but they couldn’t determine his identity, that is, until they got a hit on a DNA profile uploaded by one of his relatives to a public genealogy database.

Though forensic genealogy falls a little outside of our mission, NIH has helped to advance the gathering of family histories and using DNA to study genealogy. In fact, my blog featured NIH-supported work that succeeded in crowdsourcing 600 years of human history.

The researchers, using the online profiles of 86 million genealogy hobbyists with their permission, assembled more than 5 million family trees. The largest totaled more than 13 million people! By merging each tree from the crowd-sourced and public data, they were able to go back about 11 generations—to the 15th century and the days of Christopher Columbus. Though they may not have caught an accused killer, these large datasets provided some novel insights into our family structures, genes, and longevity.

An Ancient Human Hybrid: Every year, researchers excavate thousands of bone fragments from the remote Denisova Cave in Siberia. One such find would later be called Denisova 11, or “Denny” for short.

Oh, what a fascinating genomic tale Denny’s sliver of bone had to tell. Denny was at least 13 years old and lived in Siberia roughly 90,000 years ago. A few years ago, an international research team found that DNA from the mitochondria in Denny’s cells came from a Neanderthal, an extinct human relative.

In 2018, Denny’s family tree got even more interesting. The team published new data showing that Denny was female and, more importantly, she was a first generation mix of a Neanderthal mother and a father who belonged to another extinct human relative called the Denisovans. The Denisovans, by the way, are the first human relatives characterized almost completely on the basis of genomics. They diverged from Neanderthals about 390,000 years ago. Until about 40,000 years ago, the two occupied the Eurasian continent—Neanderthals to the west, and Denisovans to the east.

Denny’s unique genealogy makes her the first direct descendant ever discovered of two different groups of early humans. While NIH didn’t directly support this research, the sequencing of the Neanderthal genome provided an essential resource.

As exciting as these breakthroughs are, they only scratch the surface of ongoing progress in biomedical research. Every field of science is generating compelling breakthroughs filled with hope and the promise to improve the lives of millions of Americans. So let’s get started with 2019 and finish out this decade with more truly amazing science!

Reference:

[1] “2018 Breakthrough of the Year,” Science, 21 December 2018.

NIH Support: These breakthroughs represent the culmination of years of research involving many investigators and the support of multiple NIH institutes.

Building a 3D Map of the Genome

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

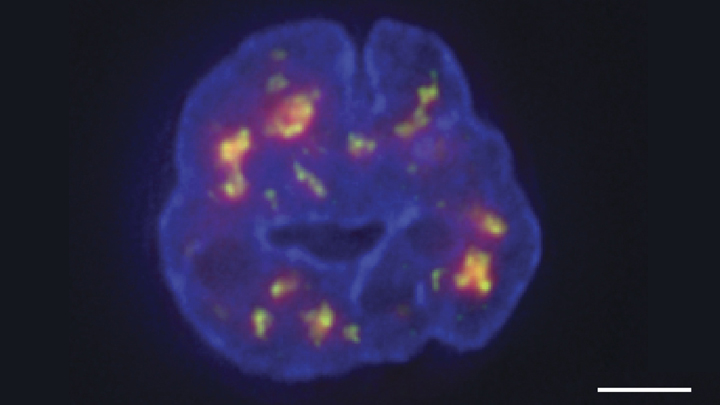

Credit: Chen et al., 2018

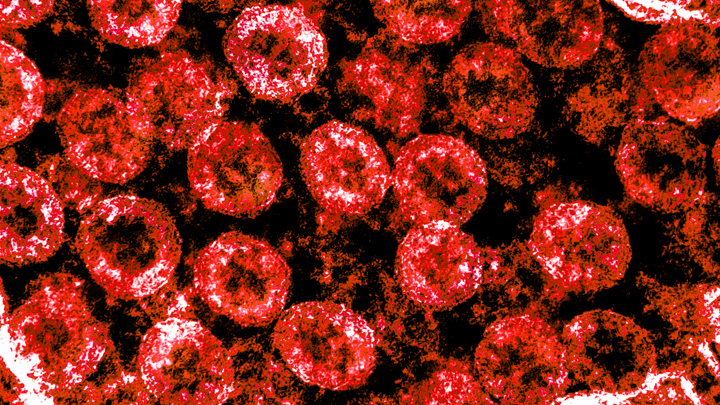

Researchers have learned a lot in recent years about how six-plus feet of human DNA gets carefully packed into a tiny cell nucleus that measures less than .00024 of an inch. Under those cramped conditions, we’ve been learning more and more about how DNA twists, turns, and spatially orients its thousands of genes within the nucleus and what this positioning might mean for health and disease.

Thanks to a new technique developed by an NIH-funded research team, there is now an even more refined view [1]. The image above features the nucleus (blue) of a human leukemia cell. The diffuse orange-red clouds highlight chemically labeled DNA found in close proximity to the tiny nuclear speckles (green). You’ll need to look real carefully to see the nuclear speckles, but these structural landmarks in the nucleus have long been thought to serve as storage sites for important cellular machinery.

Creative Minds: Studying the Human Genome in 3D

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

As a kid, Jesse Dixon often listened to his parents at the dinner table discussing how to run experiments and their own research laboratories. His father Jack is an internationally renowned biochemist and the former vice president and chief scientific officer of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. His mother Claudia Kent Dixon, now retired, did groundbreaking work in the study of lipid molecules that serve as the building blocks of cell membranes.

So, when Jesse Dixon set out to pursue a career, he followed in his parents’ footsteps and chose science. But Dixon, a researcher at the Salk Institute, La Jolla, CA, has charted a different research path by studying genomics, with a focus on understanding chromosomal structure. Dixon has now received a 2016 NIH Director’s Early Independence Award to study the three-dimensional organization of the genome, and how changes in its structure might contribute to diseases such as cancer or even to physical differences among people.

Creative Minds: A New Mechanism for Epigenetics?

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

To learn more about how DNA and inheritance works, Keith Maggert has spent much of his nearly 30 years as a researcher studying what takes place not just within the DNA genome but also the subtle modifications of it. That’s where a stable of enzymes add chemical marks to DNA, turning individual genes on or off without changing their underlying sequence. What’s really intrigued Maggert is these “epigenetic” modifications are maintained through cell division and can even get passed down from parent to child over many generations. Like many researchers, he wants to know how it happens.

Maggert thinks there’s more to the story than scientists have realized. Now an associate professor at the University of Arizona College of Medicine, Tucson, he suspects that a prominent subcellular structure in the nucleus called the nucleolus also exerts powerful epigenetic effects. What’s different about the nucleolus, Maggert proposes, is it doesn’t affect genes one by one, a focal point of current epigenetic research. He thinks under some circumstances its epigenetic effects can activate many previously silenced, or “off” genes at once, sending cells and individuals on a different path toward health or disease.

Maggert has received a 2016 NIH Director’s Transformative Research Award to pursue this potentially new paradigm. If correct, it would transform current thinking in the field and provide an exciting new perspective to track epigenetics and its contributions to a wide range of human diseases, including cancer, cardiovascular disease, and neurodegenerative disorders.

Next Page