immune system

Immune Checkpoint Discovery Has Implications for Treating Cancer and Autoimmune Diseases

Posted on by Dr. Monica M. Bertagnolli

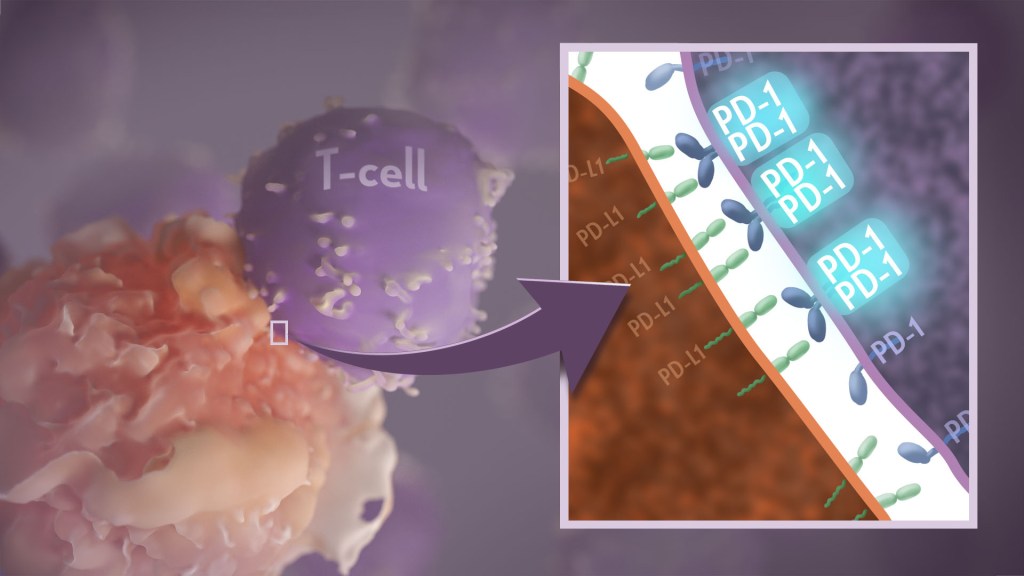

Your immune system should ideally recognize and attack infectious invaders and cancerous cells. But the system requires safety mechanisms, or brakes, to keep it from damaging healthy cells. To do this, T cells—the immune system’s most powerful attackers—rely on immune “checkpoints” to turn immune activation down when they receive the right signal. While these interactions have been well studied, a research team supported in part by NIH has made an unexpected discovery into how a key immune checkpoint works, with potentially important implications for therapies designed to boost or dampen immune activity to treat cancer and autoimmune diseases.1

The checkpoint in question is a protein called programmed cell death-1 (PD-1). Here’s how it works: PD-1 is a receptor on the surface of T cells, where it latches onto certain proteins, known as PD-L1 and PD-L2, on the surface of other cells in the body. When this interaction occurs, a signal is sent to the T cells that stops them from attacking these other cells.

Cancer cells often take advantage of this braking system, producing copious amounts of PD-L1 on their surface, allowing them to hide from T cells. An effective class of immunotherapy drugs used to treat many cancers works by blocking the interaction between PD-1 and PD-L1, to effectively release the brakes on the immune system to allow the T cells to unleash an assault on cancer cells. Researchers have also developed potential treatments for autoimmune diseases that take the opposite tact: stimulating PD-1 interaction to keep T cells inactive. These PD-1 “agonists” have shown promise in clinical trials as treatments for certain autoimmune diseases.

However, to fulfill the promise of these approaches for treating cancer and autoimmune diseases, a better understanding of precisely how PD-1 works to suppress T cell activity is still needed. The thinking has long been that individual PD-1 receptors act alone. But, as reported in Science Immunology, it turns out that this may not usually be the case. A team led by Jun Wang and Xiangpeng Kong of New York University Langone Health’s Perlmutter Cancer Center, with Elliot Philips of NYU and Michael Dustin of the University of Oxford, U.K., used sophisticated techniques to look for evidence of what happens when PD-1 proteins work together in pairs.

They found that PD-1’s tendency to link, or not link, with a second PD-1 protein to form what’s known as a “dimer” depends on interactions with portions of the protein that cross the immune cell membrane. They also found that, when PD-1 receptors pair up, they do a better job of squashing immune responses. The findings also showed that a single change in the amino acid structure in the portion of PD-1 that crosses the cell membrane can strengthen or weaken immune responses.

One reason why these fundamental discoveries are exciting is they suggest that interfering with PD-1’s ability to form dimers might make immunotherapy treatments for cancer more effective. In addition, treatments that strengthen interactions between paired PD-1 receptors might aid in the design of promising new drug classes that are intended to tamp down inflammation seen in people with some autoimmune diseases, including rheumatoid arthritis, lupus, and type 1 diabetes. The research team now plans to conduct further investigations of PD-1 blockers and agonists to explore whether these findings could eventually lead to more effective treatments for both cancer and autoimmune diseases.

Reference:

[1] Philips EA, et al. Transmembrane domain-driven PD-1 dimers mediate T cell inhibition. Science Immunology. DOI: 10.1126/sciimmunol.ade6256 (2024).

NIH Support: National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Cancer Institute, National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases, National Institute of General Medical Sciences

Immune Resilience is Key to a Long and Healthy Life

Posted on by Lawrence Tabak, D.D.S., Ph.D.

Do you feel as if you or perhaps your family members are constantly coming down with illnesses that drag on longer than they should? Or, maybe you’re one of those lucky people who rarely becomes ill and, if you do, recovers faster than others.

It’s clear that some people generally are more susceptible to infectious illnesses, while others manage to stay healthier or bounce back more quickly, sometimes even into old age. Why is this? A new study from an NIH-supported team has an intriguing answer [1]. The difference, they suggest, may be explained in part by a new measure of immunity they call immune resilience—the ability of the immune system to rapidly launch attacks that defend effectively against infectious invaders and respond appropriately to other types of inflammatory stressors, including aging or other health conditions, and then quickly recover, while keeping potentially damaging inflammation under wraps.

The findings in the journal Nature Communications come from an international team led by Sunil Ahuja, University of Texas Health Science Center and the Department of Veterans Affairs Center for Personalized Medicine, both in San Antonio. To understand the role of immune resilience and its effect on longevity and health outcomes, the researchers looked at multiple other studies including healthy individuals and those with a range of health conditions that challenged their immune systems.

By looking at multiple studies in varied infectious and other contexts, they hoped to find clues as to why some people remain healthier even in the face of varied inflammatory stressors, ranging from mild to more severe. But to understand how immune resilience influences health outcomes, they first needed a way to measure or grade this immune attribute.

The researchers developed two methods for measuring immune resilience. The first metric, a laboratory test called immune health grades (IHGs), is a four-tier grading system that calculates the balance between infection-fighting CD8+ and CD4+ T-cells. IHG-I denotes the best balance tracking the highest level of resilience, and IHG-IV denotes the worst balance tracking the lowest level of immune resilience. An imbalance between the levels of these T cell types is observed in many people as they age, when they get sick, and in people with autoimmune diseases and other conditions.

The researchers also developed a second metric that looks for two patterns of expression of a select set of genes. One pattern associated with survival and the other with death. The survival-associated pattern is primarily related to immune competence, or the immune system’s ability to function swiftly and restore activities that encourage disease resistance. The mortality-associated genes are closely related to inflammation, a process through which the immune system eliminates pathogens and begins the healing process but that also underlies many disease states.

Their studies have shown that high expression of the survival-associated genes and lower expression of mortality-associated genes indicate optimal immune resilience, correlating with a longer lifespan. The opposite pattern indicates poor resilience and a greater risk of premature death. When both sets of genes are either low or high at the same time, immune resilience and mortality risks are more moderate.

In the newly reported study initiated in 2014, Ahuja and his colleagues set out to assess immune resilience in a collection of about 48,500 people, with or without various acute, repetitive, or chronic challenges to their immune systems. In an earlier study, the researchers showed that this novel way to measure immune status and resilience predicted hospitalization and mortality during acute COVID-19 across a wide age spectrum [2].

The investigators have analyzed stored blood samples and publicly available data representing people, many of whom were healthy volunteers, who had enrolled in different studies conducted in Africa, Europe, and North America. Volunteers ranged in age from 9 to 103 years. They also evaluated participants in the Framingham Heart Study, a long-term effort to identify common factors and characteristics that contribute to cardiovascular disease.

To examine people with a wide range of health challenges and associated stresses on their immune systems, the team also included participants who had influenza or COVID-19, and people living with HIV. They also included kidney transplant recipients, people with lifestyle factors that put them at high risk for sexually transmitted infections, and people who’d had sepsis, a condition in which the body has an extreme and life-threatening response following an infection.

The question in all these contexts was the same: How well did the two metrics of immune resilience predict an individual’s health outcomes and lifespan? The short answer is that immune resilience, longevity, and better health outcomes tracked together well. Those with metrics indicating optimal immune resilience generally had better health outcomes and lived longer than those who had lower scores on the immunity grading scale. Indeed, those with optimal immune resilience were more likely to:

- Live longer,

- Resist HIV infection or the progression from HIV to AIDS,

- Resist symptomatic influenza,

- Resist a recurrence of skin cancer after a kidney transplant,

- Survive COVID-19, and

- Survive sepsis.

The study also revealed other interesting findings. While immune resilience generally declines with age, some people maintain higher levels of immune resilience as they get older for reasons that aren’t yet known, according to the researchers. Some people also maintain higher levels of immune resilience despite the presence of inflammatory stress to their immune systems such as during HIV infection or acute COVID-19. People of all ages can show high or low immune resilience. The study also found that higher immune resilience is more common in females than it is in males.

The findings suggest that there is a lot more to learn about why people differ in their ability to preserve optimal immune resilience. With further research, it may be possible to develop treatments or other methods to encourage or restore immune resilience as a way of improving general health, according to the study team.

The researchers suggest it’s possible that one day checkups of a person’s immune resilience could help us to understand and predict an individual’s health status and risk for a wide range of health conditions. It could also help to identify those individuals who may be at a higher risk of poor outcomes when they do get sick and may need more aggressive treatment. Researchers may also consider immune resilience when designing vaccine clinical trials.

A more thorough understanding of immune resilience and discovery of ways to improve it may help to address important health disparities linked to differences in race, ethnicity, geography, and other factors. We know that healthy eating, exercising, and taking precautions to avoid getting sick foster good health and longevity; in the future, perhaps we’ll also consider how our immune resilience measures up and take steps to achieve or maintain a healthier, more balanced, immunity status.

References:

[1] Immune resilience despite inflammatory stress promotes longevity and favorable health outcomes including resistance to infection. Ahuja SK, Manoharan MS, Lee GC, McKinnon LR, Meunier JA, Steri M, Harper N, Fiorillo E, Smith AM, Restrepo MI, Branum AP, Bottomley MJ, Orrù V, Jimenez F, Carrillo A, Pandranki L, Winter CA, Winter LA, Gaitan AA, Moreira AG, Walter EA, Silvestri G, King CL, Zheng YT, Zheng HY, Kimani J, Blake Ball T, Plummer FA, Fowke KR, Harden PN, Wood KJ, Ferris MT, Lund JM, Heise MT, Garrett N, Canady KR, Abdool Karim SS, Little SJ, Gianella S, Smith DM, Letendre S, Richman DD, Cucca F, Trinh H, Sanchez-Reilly S, Hecht JM, Cadena Zuluaga JA, Anzueto A, Pugh JA; South Texas Veterans Health Care System COVID-19 team; Agan BK, Root-Bernstein R, Clark RA, Okulicz JF, He W. Nat Commun. 2023 Jun 13;14(1):3286. doi: 10.1038/s41467-023-38238-6. PMID: 37311745.

[2] Immunologic resilience and COVID-19 survival advantage. Lee GC, Restrepo MI, Harper N, Manoharan MS, Smith AM, Meunier JA, Sanchez-Reilly S, Ehsan A, Branum AP, Winter C, Winter L, Jimenez F, Pandranki L, Carrillo A, Perez GL, Anzueto A, Trinh H, Lee M, Hecht JM, Martinez-Vargas C, Sehgal RT, Cadena J, Walter EA, Oakman K, Benavides R, Pugh JA; South Texas Veterans Health Care System COVID-19 Team; Letendre S, Steri M, Orrù V, Fiorillo E, Cucca F, Moreira AG, Zhang N, Leadbetter E, Agan BK, Richman DD, He W, Clark RA, Okulicz JF, Ahuja SK. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2021 Nov;148(5):1176-1191. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2021.08.021. Epub 2021 Sep 8. PMID: 34508765; PMCID: PMC8425719.

Links:

COVID-19 Research (NIH)

HIV Info (NIH)

Sepsis (National Institute of General Medical Sciences/NIH)

Sunil Ahuja (University of Texas Health Science Center, San Antonio)

Framingham Heart Study (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute/NIH)

“A Secret to Health and Long Life? Immune Resilience, NIAID Grantees Report,” NIAID Now Blog, June 13, 2023

NIH Support: National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases; National Institute on Aging; National Institute of Mental Health; National Institute of General Medical Sciences; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute

Encouraging First-in-Human Results for a Promising HIV Vaccine

Posted on by Lawrence Tabak, D.D.S., Ph.D.

In recent years, we’ve witnessed some truly inspiring progress in vaccine development. That includes the mRNA vaccines that were so critical during the COVID-19 pandemic, the first approved vaccine for respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), and a “universal flu vaccine” candidate that could one day help to thwart future outbreaks of more novel influenza viruses.

Inspiring progress also continues to be made toward a safe and effective vaccine for HIV, which still infects about 1.5 million people around the world each year [1]. A prime example is the recent first-in-human trial of an HIV vaccine made in the lab from a unique protein nanoparticle, a molecular construct measuring just a few billionths of a meter.

The results of this early phase clinical study, published recently in the journal Science Translational Medicine [2] and earlier in Science [3], showed that the experimental HIV nanoparticle vaccine is safe in people. While this vaccine alone will not offer HIV protection and is intended to be part of an eventual broader, multistep vaccination regimen, the researchers also determined that it elicited a robust immune response in nearly all 36 healthy adult volunteers.

How robust? The results show that the nanoparticle vaccine, known by the lab name eOD-GT8 60-mer, successfully expanded production of a rare type of antibody-producing immune B cell in nearly all recipients.

What makes this rare type of B cell so critical is that it is the cellular precursor of other B cells capable of producing broadly neutralizing antibodies (bnAbs) to protect against diverse HIV variants. Also very good news, the vaccine elicited broad responses from helper T cells. They play a critical supportive role for those essential B cells and their development of the needed broadly neutralizing antibodies.

For decades, researchers have brought a wealth of ideas to bear on developing a safe and effective HIV vaccine. However, crossing the finish line—an FDA-approved vaccine—has proved profoundly difficult.

A major reason is the human immune system is ill equipped to recognize HIV and produce the needed infection-fighting antibodies. And yet the medical literature includes reports of people with HIV who have produced the needed antibodies, showing that our immune system can do it.

But these people remain relatively rare, and the needed robust immunity clocks in only after many years of infection. On top of that, HIV has a habit of mutating rapidly to produce a wide range of identity-altering variants. For a vaccine to work, it most likely will need to induce the production of bnAbs that recognize and defend against not one, but the many different faces of HIV.

To make the uncommon more common became the quest of a research team that includes scientists William Schief, Scripps Research and IAVI Neutralizing Antibody Center, La Jolla, CA; M. Juliana McElrath, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center, Seattle; and Kristen Cohen, a former member of the McElrath lab now at Moderna, Cambridge, MA. The team, with NIH collaborators and support, has been plotting out a stepwise approach to train the immune system into making the needed bnAbs that recognize many HIV variants.

The critical first step is to prime the immune system to make more of those coveted bnAb-precursor B cells. That’s where the protein nanoparticle known as eOD-GT8 60-mer enters the picture.

This nanoparticle, administered by injection, is designed to mimic a small, highly conserved segment of an HIV protein that allows the virus to bind and infect human cells. In the body, those nanoparticles launch an immune response and then quickly vanish. But because this important protein target for HIV vaccines is so tiny, its signal needed amplification for immune system detection.

To boost the signal, the researchers started with a bacterial protein called lumazine synthase (LumSyn). It forms the scaffold, or structural support, of the self-assembling nanoparticle. Then, they added to the LumSyn scaffold 60 copies of the key HIV protein. This louder HIV signal is tailored to draw out and engage those very specific B cells with the potential to produce bnAbs.

As the first-in-human study showed, the nanoparticle vaccine was safe when administered twice to each participant eight weeks apart. People reported only mild to moderate side effects that went away in a day or two. The vaccine also boosted production of the desired B cells in all but one vaccine recipient (35 of 36). The idea is that this increase in essential B cells sets the stage for the needed additional steps—booster shots that can further coax these cells along toward making HIV protective bnAbs.

The latest finding in Science Translational Medicine looked deeper into the response of helper T cells in the same trial volunteers. Again, the results appear very encouraging. The researchers observed CD4 T cells specific to the HIV protein and to the LumSyn in 84 percent and 93 percent of vaccine recipients. Their analyses also identified key hotspots that the T cells recognized, which is important information for refining future vaccines to elicit helper T cells.

The team reports that they’re now collaborating with Moderna, the developer of one of the two successful mRNA-based COVID-19 vaccines, on an mRNA version of eOD-GT8 60-mer. That’s exciting because mRNA vaccines are much faster and easier to produce and modify, which should now help to move this line of research along at a faster clip.

Indeed, two International AIDS Vaccine Initiative (IAVI)-sponsored clinical trials of the mRNA version are already underway, one in the U.S. and the other in Rwanda and South Africa [4]. It looks like this team and others are now on a promising track toward following the basic science and developing a multistep HIV vaccination regimen that guides the immune response and its stepwise phases in the right directions.

As we look back on more than 40 years of HIV research, it’s heartening to witness the progress that continues toward ending the HIV epidemic. This includes the recent FDA approval of the drug Apretude, the first injectable treatment option for pre-exposure prevention of HIV, and the continued global commitment to produce a safe and effective vaccine.

References:

[1] Global HIV & AIDS statistics fact sheet. UNAIDS.

[2] A first-in-human germline-targeting HIV nanoparticle vaccine induced broad and publicly targeted helper T cell responses. Cohen KW, De Rosa SC, Fulp WJ, deCamp AC, Fiore-Gartland A, Laufer DS, Koup RA, McDermott AB, Schief WR, McElrath MJ. Sci Transl Med. 2023 May 24;15(697):eadf3309.

[3] Vaccination induces HIV broadly neutralizing antibody precursors in humans. Leggat DJ, Cohen KW, Willis JR, Fulp WJ, deCamp AC, Koup RA, Laufer DS, McElrath MJ, McDermott AB, Schief WR. Science. 2022 Dec 2;378(6623):eadd6502.

[4] IAVI and Moderna launch first-in-Africa clinical trial of mRNA HIV vaccine development program. IAVI. May 18, 2022.

Links:

Progress Toward an Eventual HIV Vaccine, NIH Research Matters, Dec. 13, 2022.

NIH Statement on HIV Vaccine Awareness Day 2023, Auchincloss H, Kapogiannis, B. May, 18, 2023.

HIV Vaccine Development (National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases/NIH)

International AIDS Vaccine Initiative (IAVI) (New York, NY)

William Schief (Scripps Research, La Jolla, CA)

Julie McElrath (Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center, Seattle, WA)

McElrath Lab (Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center, Seattle, WA)

NIH Support: National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases

Teaching the Immune System to Attack Cancer with Greater Precision

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

To protect humans from COVID-19, the Pfizer and Moderna mRNA vaccines program human cells to translate the injected synthetic messenger RNA into the coronavirus spike protein, which then primes the immune system to arm itself against future appearances of that protein. It turns out that the immune system can also be trained to spot and attack distinctive proteins on cancer cells, killing them and leaving healthy cells potentially untouched.

While these precision cancer vaccines remain experimental, researchers continue to make basic discoveries that move the field forward. That includes a recent NIH-funded study in mice that helps to refine the selection of protein targets on tumors as a way to boost the immune response [1]. To enable this boost, the researchers first had to discover a possible solution to a longstanding challenge in developing precision cancer vaccines: T cell exhaustion.

The term refers to the immune system’s complement of T cells and their capacity to learn to recognize foreign proteins, also known as neoantigens, and attack them on cancer cells to shrink tumors. But these responding T cells can exhaust themselves attacking tumors, limiting the immune response and making its benefits short-lived.

In this latest study, published in the journal Cell, Tyler Jacks and Megan Burger, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, help to explain this phenomenon of T cell exhaustion. The researchers found in mice with lung tumors that the immune system initially responds as it should. It produces lots of T cells that target many different cancer-specific proteins.

Yet there’s a problem: various subsets of T cells get in each other’s way. They compete until, eventually, one of those subsets becomes the dominant T cell type. Even when those dominant T cells grow exhausted, they still remain in the tumor and keep out other T cells, which might otherwise attack different neoantigens in the cancer.

Building on this basic discovery, the researchers came up with a strategy for developing cancer vaccines that can “awaken” T cells and reinvigorate the body’s natural cancer-fighting abilities. The strategy might seem counterintuitive. The researchers vaccinated mice with neoantigens that provide a weak but encouraging signal to the immune cells responsible for presenting the distinctive cancer protein target, or antigen, to T cells. It’s those T cells that tend to get suppressed in competition with other T cells.

When the researchers vaccinated the mice with one of those neoantigens, the otherwise suppressed T cells grew in numbers and better targeted the tumor. What’s more, the tumors shrank by more than 25 percent on average.

Research on this new strategy remains in its early stages. The researchers hope to learn if this approach to cancer vaccines might work even better when used in combination with immunotherapy drugs, which unleash the immune system against cancer in other ways.

It’s also possible that the recent and revolutionary success of mRNA vaccines for preventing COVID-19 actually could help. An important advantage of mRNA is that it’s easy for researchers to synthesize once they know the specific nucleic acid sequence of a protein target, and they can even combine different mRNA sequences to make a multiplex vaccine that primes the immune system to recognize multiple neoantigens. Now that we’ve seen how well mRNA vaccines work to prompt a desired immune response against COVID-19, this same technology can be used to speed the development and testing of future vaccines, including those designed precisely to fight cancer.

Reference:

[1] Antigen dominance hierarchies shape TCF1+ progenitor CD8 T cell phenotypes in tumors. Burger ML, Cruz AM, Crossland GE, Gaglia G, Ritch CC, Blatt SE, Bhutkar A, Canner D, Kienka T, Tavana SZ, Barandiaran AL, Garmilla A, Schenkel JM, Hillman M, de Los Rios Kobara I, Li A, Jaeger AM, Hwang WL, Westcott PMK, Manos MP, Holovatska MM, Hodi FS, Regev A, Santagata S, Jacks T. Cell. 2021 Sep 16;184(19):4996-5014.e26.

Links:

Cancer Treatment Vaccines (National Cancer Institute/NIH)

The Jacks Lab (Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge)

NIH Support: National Cancer Institute; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute

Immune Macrophages Use Their Own ‘Morse Code’

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

In the language of Morse code, the letter “S” is three short sounds and the letter “O” is three longer sounds. Put them together in the right order and you have a cry for help: S.O.S. Now an NIH-funded team of researchers has cracked a comparable code that specialized immune cells called macrophages use to signal and respond to a threat.

In fact, by “listening in” on thousands of macrophages over time, one by one, the researchers have identified not just a lone distress signal, or “word,” but a vocabulary of six words. Their studies show that macrophages use these six words at different times to launch an appropriate response. What’s more, they have evidence that autoimmune conditions can arise when immune cells misuse certain words in this vocabulary. This bad communication can cause them incorrectly to attack substances produced by the immune system itself as if they were a foreign invaders.

The findings, published recently in the journal Immunity, come from a University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) team led by Alexander Hoffmann and Adewunmi Adelaja. As an example of this language of immunity, the video above shows in both frames many immune macrophages (blue and red). You may need to watch the video four times to see what’s happening (I did). Each time you run the video, focus on one of the highlighted cells (outlined in white or green), and note how its nuclear signal intensity varies over time. That signal intensity is plotted in the rectangular box at the bottom.

The macrophages come from a mouse engineered in such a way that cells throughout its body light up to reveal the internal dynamics of an important immune signaling protein called nuclear NFκB. With the cells illuminated, the researchers could watch, or “listen in,” on this important immune signal within hundreds of individual macrophages over time to attempt to recognize and begin to interpret potentially meaningful patterns.

On the left side, macrophages are responding to an immune activating molecule called TNF. On the right, they’re responding to a bacterial toxin called LPS. While the researchers could listen to hundreds of cells at once, in the video they’ve randomly selected two cells (outlined in white or green) on each side to focus on in this example.

As shown in the box in the lower portion of each frame, the cells didn’t respond in precisely the same way to the same threat, just like two people might pronounce the same word slightly differently. But their responses nevertheless show distinct and recognizable patterns. Each of those distinct patterns could be decomposed into six code words. Together these six code words serve as a previously unrecognized immune language!

Overall, the researchers analyzed how more than 12,000 macrophage cells communicated in response to 27 different immune threats. Based on the possible arrangement of temporal nuclear NFκB dynamics, they then generated a list of more than 900 pattern features that could be potential “code words.”

Using an algorithm developed decades ago for the telecommunications industry, they then monitored which of the potential words showed up reliably when macrophages responded to a particular threatening stimulus, such as a bacterial or viral toxin. This narrowed their list to six specific features, or “words,” that correlated with a particular response.

To confirm that these pattern features contained meaning, the team turned to machine learning. If they taught a computer just those six words, they asked, could it distinguish the external threats to which the computerized cells were responding? The answer was yes.

But what if the computer had five words available, instead of six? The researchers found that the computer made more mistakes in recognizing the stimulus, leading the team to conclude that all six words are indeed needed for reliable cellular communication.

To begin to explore the implications of their findings for understanding autoimmune diseases, the researchers conducted similar studies in macrophages from a mouse model of Sjögren’s syndrome, a systemic condition in which the immune system often misguidedly attacks cells that produce saliva and tears. When they listened in on these cells, they found that they used two of the six words incorrectly. As a result, they activated the wrong responses, causing the body to mistakenly perceive a serious threat and attack itself.

While previous studies have proposed that immune cells employ a language, this is the first to identify words in that language, and to show what can happen when those words are misused. Now that researchers have a list of words, the next step is to figure out their precise definitions and interpretations [2] and, ultimately, how their misuse may be corrected to treat immunological diseases.

References:

[1] Six distinct NFκB signaling codons convey discrete information to distinguish stimuli and enable appropriate macrophage responses. Adelaja A, Taylor B, Sheu KM, Liu Y, Luecke S, Hoffmann A. Immunity. 2021 May 11;54(5):916-930.e7.

[2] NF-κB dynamics determine the stimulus specificity of epigenomic reprogramming in macrophages. Cheng QJ, Ohta S, Sheu KM, Spreafico R, Adelaja A, Taylor B, Hoffmann A. Science. 2021 Jun 18;372(6548):1349-1353.

Links:

Overview of the Immune System (National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases/NIH)

Sjögren’s Syndrome (National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research/NIH)

Alexander Hoffmann (UCLA)

NIH Support: National Institute of General Medical Sciences; National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases

Building a Better Bacterial Trap for Sepsis

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Spiders spin webs to catch insects for dinner. It turns out certain human immune cells, called neutrophils, do something similar to trap bacteria in people who develop sepsis, an uncontrolled, systemic infection that poses a major challenge in hospitals.

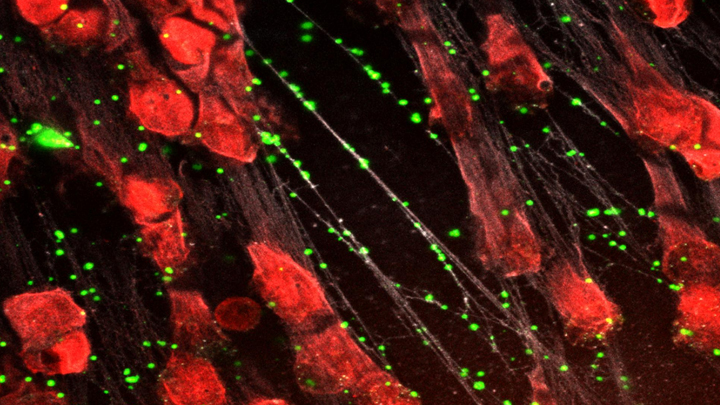

When activated to catch sepsis-causing bacteria or other pathogens, neutrophils rupture and spew sticky, spider-like webs made of DNA and antibacterial proteins. Here in red you see one of these so-called neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) that’s ensnared Staphylococcus aureus (green), a type of bacteria known for causing a range of illnesses from skin infections to pneumonia.

Yet this image, which comes from Kandace Gollomp and Mortimer Poncz at The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, is much more than a fascinating picture. It demonstrates a potentially promising new way to treat sepsis.

The researchers’ strategy involves adding a protein called platelet factor 4 (PF4), which is released by clot-forming blood platelets, to the NETs. PF4 readily binds to NETs and enhances their capture of bacteria. A modified antibody (white), which is a little hard to see, coats the PF4-bound NET above. This antibody makes the NETs even better at catching and holding onto bacteria. Other immune cells then come in to engulf and clean up the mess.

Until recently, most discussions about NETs assumed they were causing trouble, and therefore revolved around how to prevent or get rid of them while treating sepsis. But such strategies faced a major obstacle. By the time most people are diagnosed with sepsis, large swaths of these NETs have already been spun. In fact, destroying them might do more harm than good by releasing entrapped bacteria and other toxins into the bloodstream.

In a recent study published in the journal Blood, Gollomp’s team proposed flipping the script [1]. Rather than prevent or destroy NETs, why not modify them to work even better to fight sepsis? Their idea: Make NETs even stickier to catch more bacteria. This would lower the number of bacteria and help people recover from sepsis.

Gollomp recalled something lab member Anna Kowalska had noted earlier in unrelated mouse studies. She’d observed that high levels of PF4 were protective in mice with sepsis. Gollomp and her colleagues wondered if the PF4 might also be used to reinforce NETs. Sure enough, Gollomp’s studies showed that PF4 will bind to NETs, causing them to condense and resist break down.

Subsequent studies in mice and with human NETs cast in a synthetic blood vessel suggest that this approach might work. Treatment with PF4 greatly increased the number of bacteria captured by NETs. It also kept NETs intact and holding tightly onto their toxic contents. As a result, mice with sepsis fared better.

Of course, mice are not humans. More study is needed to see if the same strategy can help people with sepsis. For example, it will be important to determine if modified NETs are difficult for the human body to clear. Also, Gollomp thinks this approach might be explored for treating other types of bacterial infections.

Still, the group’s initial findings come as encouraging news for hospital staff and administrators. If all goes well, a future treatment based on this intriguing strategy may one day help to reduce the 270,000 sepsis-related deaths in the U.S. and its estimated more than $24 billion annual price tag for our nation’s hospitals [2, 3].

References:

[1] Fc-modified HIT-like monoclonal antibody as a novel treatment for sepsis. Gollomp K, Sarkar A, Harikumar S, Seeholzer SH, Arepally GM, Hudock K, Rauova L, Kowalska MA, Poncz M. Blood. 2020 Mar 5;135(10):743-754.

[2] Sepsis, Data & Reports, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Feb. 14, 2020.

[3] National inpatient hospital costs: The most expensive conditions by payer, 2013: Statistical Brief #204. Torio CM, Moore BJ. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) Statistical Briefs. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2016 May.

Links:

Sepsis (National Institute of General Medical Sciences/NIH)

Kandace Gollomp (The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, PA)

Mortimer Poncz (The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, PA)

NIH Support: National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute

Genes, Blood Type Tied to Risk of Severe COVID-19

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Credit: National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, NIH

Many people who contract COVID-19 have only a mild illness, or sometimes no symptoms at all. But others develop respiratory failure that requires oxygen support or even a ventilator to help them recover [1]. It’s clear that this happens more often in men than in women, as well as in people who are older or who have chronic health conditions. But why does respiratory failure also sometimes occur in people who are young and seemingly healthy?

A new study suggests that part of the answer to this question may be found in the genes that each one of us carries [2]. While more research is needed to pinpoint the precise underlying genes and mechanisms responsible, a recent genome-wide association (GWAS) study, just published in the New England Journal of Medicine, finds that gene variants in two regions of the human genome are associated with severe COVID-19 and correspondingly carry a greater risk of COVID-19-related death.

The two stretches of DNA implicated as harboring risks for severe COVID-19 are known to carry some intriguing genes, including one that determines blood type and others that play various roles in the immune system. In fact, the findings suggest that people with blood type A face a 50 percent greater risk of needing oxygen support or a ventilator should they become infected with the novel coronavirus. In contrast, people with blood type O appear to have about a 50 percent reduced risk of severe COVID-19.

These new findings—the first to identify statistically significant susceptibility genes for the severity of COVID-19—come from a large research effort led by Andre Franke, a scientist at Christian-Albrecht-University, Kiel, Germany, along with Tom Karlsen, Oslo University Hospital Rikshospitalet, Norway. Their study included 1,980 people undergoing treatment for severe COVID-19 and respiratory failure at seven medical centers in Italy and Spain.

In search of gene variants that might play a role in the severe illness, the team analyzed patient genome data for more than 8.5 million so-called single-nucleotide polymorphisms, or SNPs. The vast majority of these single “letter” nucleotide substitutions found all across the genome are of no health significance, but they can help to pinpoint the locations of gene variants that turn up more often in association with particular traits or conditions—in this case, COVID-19-related respiratory failure. To find them, the researchers compared SNPs in people with severe COVID-19 to those in more than 1,200 healthy blood donors from the same population groups.

The analysis identified two places that turned up significantly more often in the individuals with severe COVID-19 than in the healthy folks. One of them is found on chromosome 3 and covers a cluster of six genes with potentially relevant functions. For instance, this portion of the genome encodes a transporter protein known to interact with angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ACE2), the surface receptor that allows the novel coronavirus that causes COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2, to bind to and infect human cells. It also encodes a collection of chemokine receptors, which play a role in the immune response in the airways of our lungs.

The other association signal popped up on chromosome 9, right over the area of the genome that determines blood type. Whether you are classified as an A, B, AB, or O blood type, depends on how your genes instruct your blood cells to produce (or not produce) a certain set of proteins. The researchers did find evidence suggesting a relationship between blood type and COVID-19 risk. They noted that this area also includes a genetic variant associated with increased levels of interleukin-6, which plays a role in inflammation and may have implications for COVID-19 as well.

These findings, completed in two months under very difficult clinical conditions, clearly warrant further study to understand the implications more fully. Indeed, Franke, Karlsen, and many of their colleagues are part of the COVID-19 Host Genetics Initiative, an ongoing international collaborative effort to learn the genetic determinants of COVID-19 susceptibility, severity, and outcomes. Some NIH research groups are taking part in the initiative, and they recently launched a study to look for informative gene variants in 5,000 COVID-19 patients in the United States and Canada.

The hope is that these and other findings yet to come will point the way to a more thorough understanding of the biology of COVID-19. They also suggest that a genetic test and a person’s blood type might provide useful tools for identifying those who may be at greater risk of serious illness.

References:

[1] Characteristics of and important lessons from the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: Summary of a report of 72 314 cases from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Wu Z, McGoogan JM, et. al. 2020 Feb 24. [published online ahead of print]

[2] Genomewide association study of severe Covid-19 with respiratory failure. Ellinghaus D, Degenhardt F, et. a. NEJM. June 17, 2020.

Links:

The COVID-19 Host Genetics Initiative

Andre Franke (Christian-Albrechts-University of Kiel, Germany)

Tom Karlsen (Oslo University Hospital Rikshospitalet, Norway)

New Study Points to Targetable Protective Factor in Alzheimer’s Disease

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

If you’ve spent time with individuals affected with Alzheimer’s disease (AD), you might have noticed that some people lose their memory and other cognitive skills more slowly than others. Why is that? New findings indicate that at least part of the answer may lie in differences in their immune responses.

Researchers have now found that slower loss of cognitive skills in people with AD correlates with higher levels of a protein that helps immune cells clear plaque-like cellular debris from the brain [1]. The efficiency of this clean-up process in the brain can be measured via fragments of the protein that shed into the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). This suggests that the protein, called TREM2, and the immune system as a whole, may be promising targets to help fight Alzheimer’s disease.

The findings come from an international research team led by Michael Ewers, Institute for Stroke and Dementia Research, Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München, Germany, and Christian Haass, Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München, Germany and German Center for Neurodegenerative Diseases. The researchers got interested in TREM2 following the discovery several years ago that people carrying rare genetic variants for the protein were two to three times more likely to develop AD late in life.

Not much was previously known about TREM2, so this finding from a genome wide association study (GWAS) was a surprise. In the brain, it turns out that TREM2 proteins are primarily made by microglia. These scavenging immune cells help to keep the brain healthy, acting as a clean-up crew that clears cellular debris, including the plaque-like amyloid-beta that is a hallmark of AD.

In subsequent studies, Haass and colleagues showed in mouse models of AD that TREM2 helps to shift microglia into high gear for clearing amyloid plaques [2]. This animal work and that of others helped to strengthen the case that TREM2 may play an important role in AD. But what did these data mean for people with this devastating condition?

There had been some hints of a connection between TREM2 and the progression of AD in humans. In the study published in Science Translational Medicine, the researchers took a deeper look by taking advantage of the NIH-funded Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI).

ADNI began more than a decade ago to develop methods for early AD detection, intervention, and treatment. The initiative makes all its data freely available to AD researchers all around the world. That allowed Ewers, Haass, and colleagues to focus their attention on 385 older ADNI participants, both with and without AD, who had been followed for an average of four years.

Their primary hypothesis was that individuals with AD and evidence of higher TREM2 levels at the outset of the study would show over the years less change in their cognitive abilities and in the volume of their hippocampus, a portion of the brain important for learning and memory. And, indeed, that’s exactly what they found.

In individuals with comparable AD, whether mild cognitive impairment or dementia, those having higher levels of a TREM2 fragment in their CSF showed a slower decline in memory. Those with evidence of a higher ratio of TREM2 relative to the tau protein in their CSF also progressed more slowly from normal cognition to early signs of AD or from mild cognitive impairment to full-blown dementia.

While it’s important to note that correlation isn’t causation, the findings suggest that treatments designed to boost TREM2 and the activation of microglia in the brain might hold promise for slowing the progression of AD in people. The challenge will be to determine when and how to target TREM2, and a great deal of research is now underway to make these discoveries.

Since its launch more than a decade ago, ADNI has made many important contributions to AD research. This new study is yet another fine example that should come as encouraging news to people with AD and their families.

References:

[1] Increased soluble TREM2 in cerebrospinal fluid is associated with reduced cognitive and clinical decline in Alzheimer’s disease. Ewers M, Franzmeier N, Suárez-Calvet M, Morenas-Rodriguez E, Caballero MAA, Kleinberger G, Piccio L, Cruchaga C, Deming Y, Dichgans M, Trojanowski JQ, Shaw LM, Weiner MW, Haass C; Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative. Sci Transl Med. 2019 Aug 28;11(507).

[2] Loss of TREM2 function increases amyloid seeding but reduces plaque-associated ApoE. Parhizkar S, Arzberger T, Brendel M, Kleinberger G, Deussing M, Focke C, Nuscher B, Xiong M, Ghasemigharagoz A, Katzmarski N, Krasemann S, Lichtenthaler SF, Müller SA, Colombo A, Monasor LS, Tahirovic S, Herms J, Willem M, Pettkus N, Butovsky O, Bartenstein P, Edbauer D, Rominger A, Ertürk A, Grathwohl SA, Neher JJ, Holtzman DM, Meyer-Luehmann M, Haass C. Nat Neurosci. 2019 Feb;22(2):191-204.

Links:

Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Dementias (National Institute on Aging/NIH)

Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (University of Southern California, Los Angeles)

Ewers Lab (University Hospital Munich, Germany)

Haass Lab (Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München, Germany)

German Center for Neurodegenerative Diseases (Bonn)

Institute for Stroke and Dementia Research (Munich, Germany)

NIH Support: National Institute on Aging

Next Page