cognition

Human Brain Compresses Working Memories into Low-Res ‘Summaries’

Posted on by Lawrence Tabak, D.D.S., Ph.D.

You have probably done it already a few times today. Paused to remember a password, a shopping list, a phone number, or maybe the score to last night’s ballgame. The ability to store and recall needed information, called working memory, is essential for most of the human brain’s higher cognitive processes.

Researchers are still just beginning to piece together how working memory functions. But recently, NIH-funded researchers added an intriguing new piece to this neurobiological puzzle: how visual working memories are “formatted” and stored in the brain.

The findings, published in the journal Neuron, show that the visual cortex—the brain’s primary region for receiving, integrating, and processing visual information from the eye’s retina—acts more like a blackboard than a camera. That is, the visual cortex doesn’t photograph all the complex details of a visual image, such as the color of paper on which your password is written or the precise series of lines that make up the letters. Instead, it recodes visual information into something more like simple chalkboard sketches.

The discovery suggests that those pared down, low-res representations serve as a kind of abstract summary, capturing the relevant information while discarding features that aren’t relevant to the task at hand. It also shows that different visual inputs, such as spatial orientation and motion, may be stored in virtually identical, shared memory formats.

The new study, from Clayton Curtis and Yuna Kwak, New York University, New York, builds upon a known fundamental aspect of working memory. Many years ago, it was determined that the human brain tends to recode visual information. For instance, if passed a 10-digit phone number on a card, the visual information gets recoded and stored in the brain as the sounds of the numbers being read aloud.

Curtis and Kwak wanted to learn more about how the brain formats representations of working memory in patterns of brain activity. To find out, they measured brain activity with functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) while participants used their visual working memory.

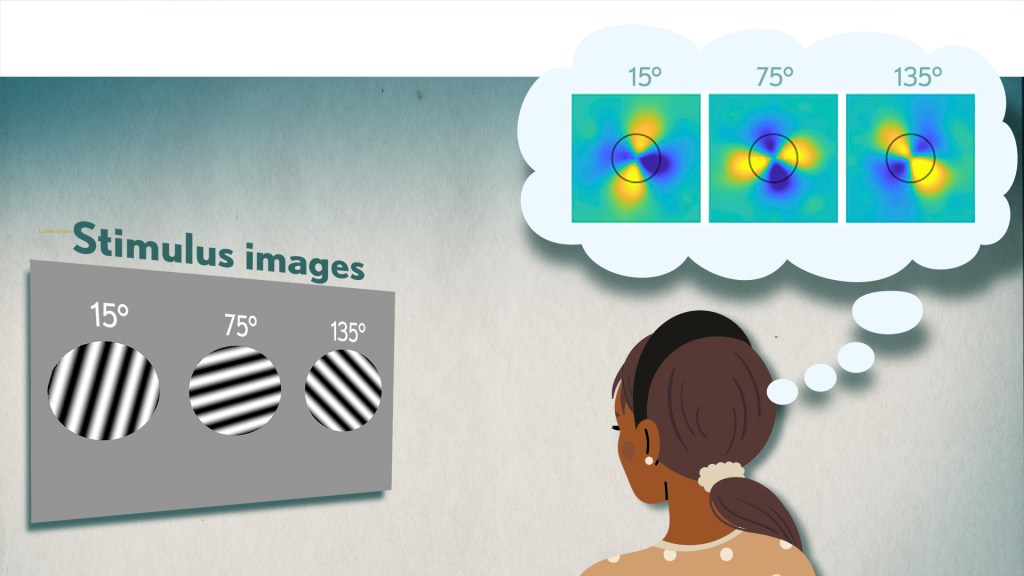

In each test, study participants were asked to remember a visual stimulus presented to them for 12 seconds and then make a memory-based judgment on what they’d just seen. In some trials, as shown in the image above, participants were shown a tilted grating, a series of black and white lines oriented at a particular angle. In others, they observed a cloud of dots, all moving in a direction to represent those same angles. After a short break, participants were asked to recall and precisely indicate the angle of the grating’s tilt or the dot cloud’s motion as accurately as possible.

It turned out that either visual stimulus—the grating or moving dots—resulted in the same patterns of neural activity in the visual cortex and parietal cortex. The parietal cortex is a part of the brain used in memory processing and storage.

These two distinct visual memories carrying the same relevant information seemed to have been recoded into a shared abstract memory format. As a result, the pattern of brain activity trained to recall motion direction was indistinguishable from that trained to recall the grating orientation.

This result indicated that only the task-relevant features of the visual stimuli had been extracted and recoded into a shared memory format. But Curtis and Kwak wondered whether there might be more to this finding.

To take a closer look, they used a sophisticated model that allowed them to project the three-dimensional patterns of brain activity into a more-informative, two-dimensional representation of visual space. And, indeed, their analysis of the data revealed a line-like pattern, similar to a chalkboard sketch that’s oriented at the relevant angles.

The findings suggest that participants weren’t actually remembering the grating or a complex cloud of moving dots at all. Instead, they’d compressed the images into a line representing the angle that they’d been asked to remember.

Many questions remain about how remembering a simple angle, a relatively straightforward memory formation, will translate to the more-complex sets of information stored in our working memory. On a technical level, though, the findings show that working memory can now be accessed and captured in ways that hadn’t been possible before. This will help to delineate the commonalities in working memory formation and the possible differences, whether it’s remembering a password, a shopping list, or the score of your team’s big victory last night.

Reference:

[1] Unveiling the abstract format of mnemonic representations. Kwak Y, Curtis CE. Neuron. 2022, April 7; 110(1-7).

Links:

Working Memory (National Institute of Mental Health/NIH)

The Curtis Lab (New York University, New York)

NIH Support: National Eye Institute

New Study Points to Targetable Protective Factor in Alzheimer’s Disease

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

If you’ve spent time with individuals affected with Alzheimer’s disease (AD), you might have noticed that some people lose their memory and other cognitive skills more slowly than others. Why is that? New findings indicate that at least part of the answer may lie in differences in their immune responses.

Researchers have now found that slower loss of cognitive skills in people with AD correlates with higher levels of a protein that helps immune cells clear plaque-like cellular debris from the brain [1]. The efficiency of this clean-up process in the brain can be measured via fragments of the protein that shed into the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). This suggests that the protein, called TREM2, and the immune system as a whole, may be promising targets to help fight Alzheimer’s disease.

The findings come from an international research team led by Michael Ewers, Institute for Stroke and Dementia Research, Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München, Germany, and Christian Haass, Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München, Germany and German Center for Neurodegenerative Diseases. The researchers got interested in TREM2 following the discovery several years ago that people carrying rare genetic variants for the protein were two to three times more likely to develop AD late in life.

Not much was previously known about TREM2, so this finding from a genome wide association study (GWAS) was a surprise. In the brain, it turns out that TREM2 proteins are primarily made by microglia. These scavenging immune cells help to keep the brain healthy, acting as a clean-up crew that clears cellular debris, including the plaque-like amyloid-beta that is a hallmark of AD.

In subsequent studies, Haass and colleagues showed in mouse models of AD that TREM2 helps to shift microglia into high gear for clearing amyloid plaques [2]. This animal work and that of others helped to strengthen the case that TREM2 may play an important role in AD. But what did these data mean for people with this devastating condition?

There had been some hints of a connection between TREM2 and the progression of AD in humans. In the study published in Science Translational Medicine, the researchers took a deeper look by taking advantage of the NIH-funded Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI).

ADNI began more than a decade ago to develop methods for early AD detection, intervention, and treatment. The initiative makes all its data freely available to AD researchers all around the world. That allowed Ewers, Haass, and colleagues to focus their attention on 385 older ADNI participants, both with and without AD, who had been followed for an average of four years.

Their primary hypothesis was that individuals with AD and evidence of higher TREM2 levels at the outset of the study would show over the years less change in their cognitive abilities and in the volume of their hippocampus, a portion of the brain important for learning and memory. And, indeed, that’s exactly what they found.

In individuals with comparable AD, whether mild cognitive impairment or dementia, those having higher levels of a TREM2 fragment in their CSF showed a slower decline in memory. Those with evidence of a higher ratio of TREM2 relative to the tau protein in their CSF also progressed more slowly from normal cognition to early signs of AD or from mild cognitive impairment to full-blown dementia.

While it’s important to note that correlation isn’t causation, the findings suggest that treatments designed to boost TREM2 and the activation of microglia in the brain might hold promise for slowing the progression of AD in people. The challenge will be to determine when and how to target TREM2, and a great deal of research is now underway to make these discoveries.

Since its launch more than a decade ago, ADNI has made many important contributions to AD research. This new study is yet another fine example that should come as encouraging news to people with AD and their families.

References:

[1] Increased soluble TREM2 in cerebrospinal fluid is associated with reduced cognitive and clinical decline in Alzheimer’s disease. Ewers M, Franzmeier N, Suárez-Calvet M, Morenas-Rodriguez E, Caballero MAA, Kleinberger G, Piccio L, Cruchaga C, Deming Y, Dichgans M, Trojanowski JQ, Shaw LM, Weiner MW, Haass C; Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative. Sci Transl Med. 2019 Aug 28;11(507).

[2] Loss of TREM2 function increases amyloid seeding but reduces plaque-associated ApoE. Parhizkar S, Arzberger T, Brendel M, Kleinberger G, Deussing M, Focke C, Nuscher B, Xiong M, Ghasemigharagoz A, Katzmarski N, Krasemann S, Lichtenthaler SF, Müller SA, Colombo A, Monasor LS, Tahirovic S, Herms J, Willem M, Pettkus N, Butovsky O, Bartenstein P, Edbauer D, Rominger A, Ertürk A, Grathwohl SA, Neher JJ, Holtzman DM, Meyer-Luehmann M, Haass C. Nat Neurosci. 2019 Feb;22(2):191-204.

Links:

Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Dementias (National Institute on Aging/NIH)

Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (University of Southern California, Los Angeles)

Ewers Lab (University Hospital Munich, Germany)

Haass Lab (Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München, Germany)

German Center for Neurodegenerative Diseases (Bonn)

Institute for Stroke and Dementia Research (Munich, Germany)

NIH Support: National Institute on Aging

Sleep Loss Encourages Spread of Toxic Alzheimer’s Protein

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

In addition to memory loss and confusion, many people with Alzheimer’s disease have trouble sleeping. Now an NIH-funded team of researchers has evidence that the reverse is also true: a chronic lack of sleep may worsen the disease and its associated memory loss.

The new findings center on a protein called tau, which accumulates in abnormal tangles in the brains of people with Alzheimer’s disease. In the healthy brain, active neurons naturally release some tau during waking hours, but it normally gets cleared away during sleep. Essentially, your brain has a system for taking the garbage out while you’re off in dreamland.

The latest findings in studies of mice and people further suggest that sleep deprivation upsets this balance, allowing more tau to be released, accumulate, and spread in toxic tangles within brain areas important for memory. While more study is needed, the findings suggest that regular and substantial sleep may play an unexpectedly important role in helping to delay or slow down Alzheimer’s disease.

It’s long been recognized that Alzheimer’s disease is associated with the gradual accumulation of beta-amyloid peptides and tau proteins, which form plaques and tangles that are considered hallmarks of the disease. It has only more recently become clear that, while beta-amyloid is an early sign of the disease, tau deposits track more closely with disease progression and a person’s cognitive decline.

Such findings have raised hopes among researchers including David Holtzman, Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, that tau-targeting treatments might slow this devastating disease. Though much of the hope has focused on developing the right drugs, some has also focused on sleep and its nightly ability to reset the brain’s metabolic harmony.

In the new study published in Science, Holtzman’s team set out to explore whether tau levels in the brain naturally are tied to the sleep-wake cycle [1]. Earlier studies had shown that tau is released in small amounts by active neurons. But when neurons are chronically activated, more tau gets released. So, do tau levels rise when we’re awake and fall during slumber?

The Holtzman team found that they do. The researchers measured tau levels in brain fluid collected from mice during their normal waking and sleeping hours. (Since mice are nocturnal, they sleep primarily during the day.) The researchers found that tau levels in brain fluid nearly double when the animals are awake. They also found that sleep deprivation caused tau levels in brain fluid to double yet again.

These findings were especially interesting because Holtzman’s team had already made a related finding in people. The team found that healthy adults forced to pull an all-nighter had a 30 percent increase on average in levels of unhealthy beta-amyloid in their cerebrospinal fluid (CSF).

The researchers went back and reanalyzed those same human samples for tau. Sure enough, the tau levels were elevated on average by about 50 percent.

Once tau begins to accumulate in brain tissue, the protein can spread from one brain area to the next along neural connections. So, Holtzman’s team wondered whether a lack of sleep over longer periods also might encourage tau to spread.

To find out, mice engineered to produce human tau fibrils in their brains were made to stay up longer than usual and get less quality sleep over several weeks. Those studies showed that, while less sleep didn’t change the original deposition of tau in the brain, it did lead to a significant increase in tau’s spread. Intriguingly, tau tangles in the animals appeared in the same brain areas affected in people with Alzheimer’s disease.

Another report by Holtzman’s team appearing early last month in Science Translational Medicine found yet another link between tau and poor sleep. That study showed that older people who had more tau tangles in their brains by PET scanning had less slow-wave, deep sleep [2].

Together, these new findings suggest that Alzheimer’s disease and sleep loss are even more intimately intertwined than had been realized. The findings suggest that good sleep habits and/or treatments designed to encourage plenty of high quality Zzzz’s might play an important role in slowing Alzheimer’s disease. On the other hand, poor sleep also might worsen the condition and serve as an early warning sign of Alzheimer’s.

For now, the findings come as an important reminder that all of us should do our best to get a good night’s rest on a regular basis. Sleep deprivation really isn’t a good way to deal with overly busy lives (I’m talking to myself here). It isn’t yet clear if better sleep habits will prevent or delay Alzheimer’s disease, but it surely can’t hurt.

References:

[1] The sleep-wake cycle regulates brain interstitial fluid tau in mice and CSF tau in humans. Holth JK, Fritschi SK, Wang C, Pedersen NP, Cirrito JR, Mahan TE, Finn MB, Manis M, Geerling JC, Fuller PM, Lucey BP, Holtzman DM. Science. 2019 Jan 24.

[2] Reduced non-rapid eye movement sleep is associated with tau pathology in early Alzheimer’s disease. Lucey BP, McCullough A, Landsness EC, Toedebusch CD, McLeland JS, Zaza AM, Fagan AM, McCue L, Xiong C, Morris JC, Benzinger TLS, Holtzman DM. Sci Transl Med. 2019 Jan 9;11(474).

Links:

Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Dementias (National Institute on Aging/NIH)

Accelerating Medicines Partnership: Alzheimer’s Disease (NIH)

Holtzman Lab (Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis)

NIH Support: National Institute on Aging; National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke; National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences; National Cancer Institute; National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering

New Evidence Suggests Aging Brains Continue to Make New Neurons

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

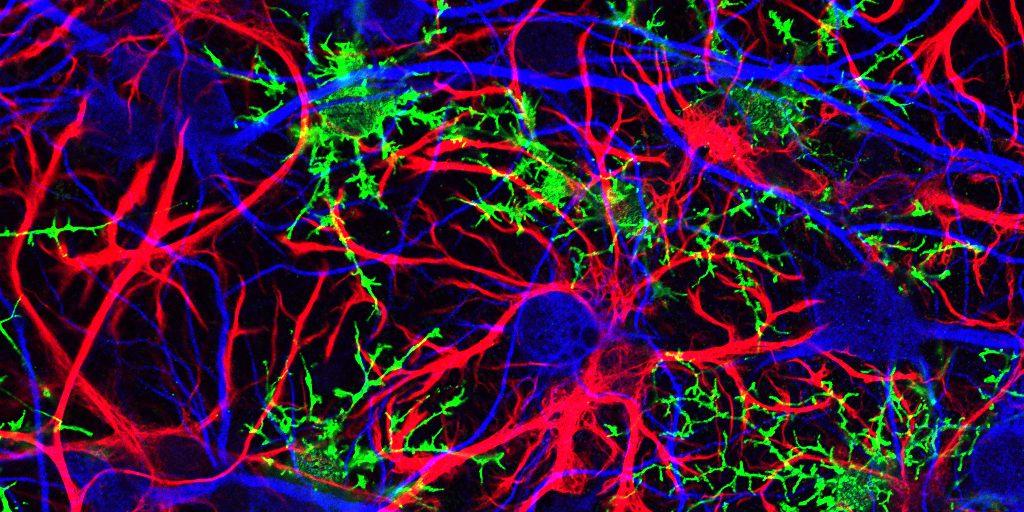

Caption: Mammalian hippocampal tissue. Immunofluorescence microscopy showing neurons (blue) interacting with neural astrocytes (red) and oligodendrocytes (green).

Credit: Jonathan Cohen, Fields Lab, Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, NIH

There’s been considerable debate about whether the human brain has the capacity to make new neurons into adulthood. Now, a recently published study offers some compelling new evidence that’s the case. In fact, the latest findings suggest that a healthy person in his or her seventies may have about as many young neurons in a portion of the brain essential for learning and memory as a teenager does.

As reported in the journal Cell Stem Cell, researchers examined the brains of healthy people, aged 14 to 79, and found similar numbers of young neurons throughout adulthood [1]. Those young neurons persisted in older brains that showed other signs of decline, including a reduced ability to produce new blood vessels and form new neural connections. The researchers also found a smaller reserve of quiescent, or inactive, neural stem cells in a brain area known to support cognitive-emotional resilience, the ability to cope with and bounce back from stressful circumstances.

While more study is clearly needed, the findings suggest healthy elderly people may have more cognitive reserve than is commonly believed. However, the findings may also help to explain why even perfectly healthy older people often find it difficult to face new challenges, such as travel or even shopping at a different grocery store, that wouldn’t have fazed them earlier in life.

Creative Minds: Helping More Kids Beat Anxiety Disorders

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

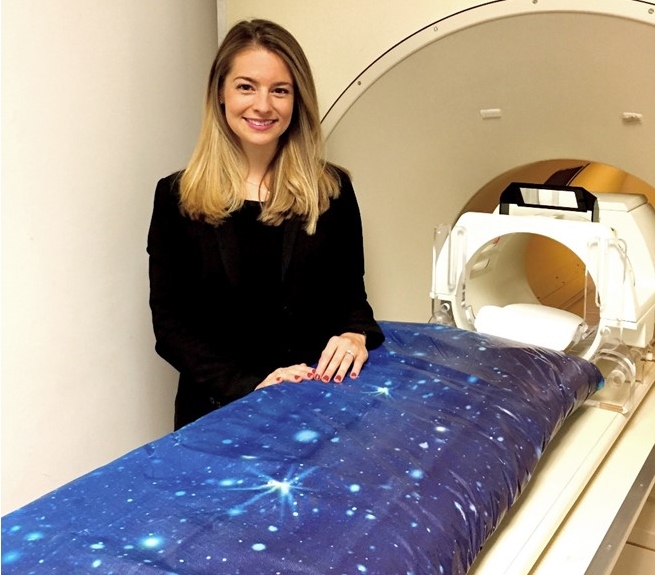

Dylan Gee

While earning her Ph.D. in clinical psychology, Dylan Gee often encountered children and adolescents battling phobias, panic attacks, and other anxiety disorders. Most overcame them with the help of psychotherapy. But not all of the kids did, and Gee spent many an hour brainstorming about how to help her tougher cases, often to find that nothing worked.

What Gee noticed was that so many of the interventions she pondered were based on studies in adults. Little was actually known about the dramatic changes that a child’s developing brain undergoes and their implications for coping under stress. Gee, an assistant professor at Yale University, New Haven, CT, decided to dedicate her research career to bridging the gap between basic neuroscience and clinical interventions to treat children and adolescents with persistent anxiety and stress-related disorders.

Making the Connections: Study Links Brain’s Wiring to Human Traits

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Caption: The wiring diagram of a human brain, measured in a healthy individual, where the movement of water molecules is measured by diffuse tensor magnetic resonance imaging, revealing the connections. This is an example of the type of work being done by the Human Connectome Project.

Source: Courtesy of the Laboratory of Neuro Imaging and Martinos Center for Biomedical Imaging, Consortium of the Human Connectome Project

For questions about why people often think, act, and perceive the world so differently, the brain is clearly an obvious place to look for answers. However, because the human brain is packed with tens of billions of neurons, which together make trillions of connections, knowing exactly where and how to look remains profoundly challenging.

Undaunted by these complexities, researchers involved in the NIH-funded Human Connectome Project (HCP) have been making progress, as shown by some intriguing recent discoveries. In a study published in Nature Neuroscience [1], an HCP team found that the brains of individuals with “positive” traits—such as strong cognitive skills and a healthy sense of well-being—show stronger connectivity in certain areas of the brain than do those with more “negative” traits—such as tendencies toward anger, rule-breaking, and substance use. While these findings are preliminary, they suggest it may be possible one day to understand, and perhaps even modify, the connections within the brain that are associated with human behavior in all its diversity.

Next Page