brain

Study Suggests Treatments that Unleash Immune Cells in the Brain Could Help Combat Alzheimer’s

Posted on by Dr. Monica M. Bertagnolli

In Alzheimer’s disease, a buildup of sticky amyloid proteins in the brain clump together to form plaques, causing damage that gradually leads to worsening dementia symptoms. A promising way to change the course of this disease is with treatments that clear away damaging amyloid plaques or stop them from forming in the first place. In fact, the Food and Drug Administration recently approved the first drug for early Alzheimer’s that moderately slows cognitive decline by reducing amyloid plaques.1 Still, more progress is needed to combat this devastating disease that as many as 6.7 million Americans were living with in 2023.

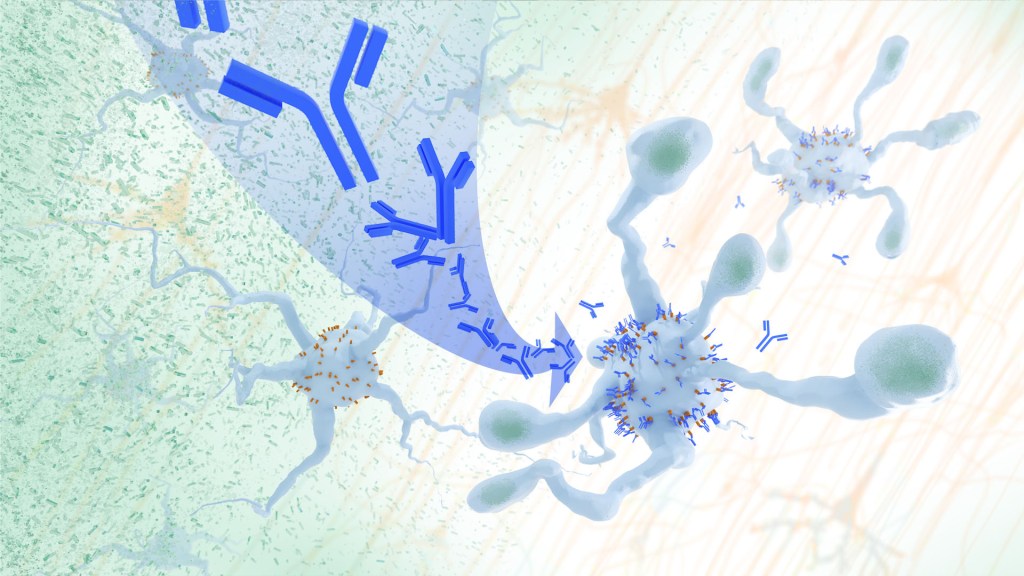

Recent findings from a study in mice, supported in part by NIH and reported in Science Translational Medicine, offer another potential way to clear amyloid plaques in the brain. The key component of this strategy is using the brain’s built-in cleanup crew for amyloid plaques and other waste products: immune cells known as microglia that naturally help to limit the progression of Alzheimer’s. The findings suggest it may be possible to develop immunotherapies—treatments that use the body’s immune system to fight disease—to activate microglia in the brains of people with Alzheimer’s and clear amyloid plaques more effectively.2

In their report, the research team—including Marco Colonna, Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, and Jinchao Hou, now at Children’s Hospital of Zhejiang University School of Medicine in Zhejiang Province, China—wrote that microglia in the brain surround plaques to create a barrier that controls their spread. Microglia can also destroy amyloid plaques directly. But how microglia work in the brain depends on a fine-tuned balance of signals that activate or inhibit them. In people with Alzheimer’s, microglia don’t do their job well enough.

The researchers suspected this might have something to do with a protein called apolipoprotein E (APOE). This protein normally helps carry cholesterol and other fats in the bloodstream. But the gene encoding the protein is known for its role in influencing a person’s risk for developing Alzheimer’s, and in the Alzheimer’s brain, the protein is a key component of amyloid plaques. The protein can also inactivate microglia by binding to a receptor called LILRB4 found on the immune cells’ surfaces.

Earlier studies in mouse models of Alzheimer’s showed that the LILRB4 receptor is expressed at high levels in microglia when amyloid plaques build up. This suggested that treatments targeting this receptor on microglia might hold promise for treating Alzheimer’s. In the new study, the research team looked for evidence that an increase in LILRB4 receptors on microglia plays an important role in the brains of people with Alzheimer’s.

To do this, the researchers first studied brain tissue samples from people who died with this disease and discovered unusually high amounts of the LILRB4 receptor on the surfaces of microglia, similar to what had been seen in the mouse models. This could help explain why microglia struggle to control amyloid plaques in the Alzheimer’s brain.

Next, the researchers conducted studies of mouse brains with accumulating amyloid plaques that express the LILRB4 receptor to see if an antibody targeting the receptor could lower amyloid levels by boosting activity of immune microglia. Their findings suggest that the antibody treatment blocked the interaction between APOE proteins and LILRB4 receptors and enabled microglia to clear amyloid plaques. Intriguingly, the team’s additional studies found that this clearing process also changed the animals’ behavior, making them less likely to take risks. That’s important because people with Alzheimer’s may engage in risky behaviors as they lack memories of earlier experiences that they could use to make decisions.

There’s plenty more to learn. For instance, the researchers don’t know yet whether this approach will affect the tau protein, which forms damaging tangles inside neurons in the Alzheimer’s brain. They also want to investigate whether this strategy of clearing amyloid plaques might come with other health risks.

But overall, these findings add to evidence that immunotherapies of this kind could be a promising way to treat Alzheimer’s. This strategy may also have implications for treating other neurodegenerative conditions characterized by toxic debris in the brain, such as Parkinson’s disease, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), and Huntington’s disease. The hope is that this kind of research will ultimately lead to more effective treatments for Alzheimer’s and other conditions affecting the brain.

References:

[1] FDA Converts Novel Alzheimer’s Disease Treatment to Traditional Approval. U.S. Food and Drug Administration (2023).

[2] Hou J, et al. Antibody-mediated targeting of human microglial leukocyte Ig-like receptor B4 attenuates amyloid pathology in a mouse model. Science Translational Medicine. DOI: 10.1126/scitranslmed.adj9052 (2024).

NIH Support: National Institute of General Medical Sciences, National Institute on Aging

Fear Switch in the Brain May Point to Target for Treating Anxiety Disorders Including PTSD

Posted on by Dr. Monica M. Bertagnolli

There’s a good reason you feel fear creep in when you’re walking alone at night in an unfamiliar place or hear a loud and unexpected noise ring out. In those moments, your brain triggers other parts of your nervous system to set a stress response in motion throughout your body. It’s that fear-driven survival response that keeps you alert, ready to fight or flee if the need arises. But when acute anxiety or traumatic events lead to fear that becomes generalized—occurring often and in situations that aren’t threatening—this can lead to debilitating anxiety disorders, including post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

Just what happens in the brain’s circuitry to turn a healthy fear response into one that’s harmful hasn’t been well understood. Now, research findings by a team led by Nicholas Spitzer and Hui-Quan Li at the University of California San Diego and reported in the journal Science have pinpointed changes in the biochemistry of the brain and neural circuitry that lead to generalized fear.1 The intriguing findings, from research supported in part by NIH, raise the possibility that it might be possible to prevent or reverse this process with treatments targeting this fear “switch.”

To investigate generalized fear in the brain, the researchers first studied mice in the lab, looking at parts of the brain known to be linked to panic-like fear responses, including an area of the brainstem known as the dorsal raphe. They found that, in the mouse brain, acute stress led to a switch in the chemical messengers, or neurotransmitters, in some neurons within this portion of the mouse brain. Specifically, the chemical signals in the neurons flipped from producing excitatory glutamate neurotransmitters to inhibitory GABA neurotransmitters, and this led to a generalized fear response. They also found that the neurons that had undergone this switch are connected to brain regions that are known to play a role in fear responses including the amygdala and lateral hypothalamus. Interestingly, the researchers also showed they could avert generalized fear responses by preventing the production of GABA in the mouse brain.

To further support their research, the study team then examined postmortem brains of people who had PTSD and confirmed a similar switch in neurotransmitters to what happened in the mice. Next, they wanted to find out if they could block the switch by treating mice with the commonly used antidepressant fluoxetine. They found that when mice were treated with fluoxetine in their drinking water promptly after a stressful event, the neurotransmitter switch and subsequent generalized fear were prevented.

The researchers made even more findings about the timing of the switch that could lead to better treatments. They found that in mice, the switch to generalized fear persisted for four weeks after an acutely stressful event—a period that for the mice may be the equivalent of three years in people. This suggests that treatments may prevent generalized fear and the development of anxiety disorders when given before the brain undergoes a neurotransmitter switch. The findings may also explain why treatment doesn’t seem to be as effective in people who are initially treated for PTSD after having it for a long time.

Going forward, the researchers want to explore targeted approaches to reversing this fear switch after it has taken place. The hope is to discover new ways to rid the brain of generalized fear responses and help treat anxiety disorders including PTSD, a condition which will affect more than six in every 100 people at some point in their lives.2

References:

[1] Li HQ, et al. Generalized fear after acute stress is caused by change in neuronal cotransmitter identity. Science. DOI: 10.1126/science.adj5996 (2024).

[2] Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). National Institute of Mental Health.

NIH Support: National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke

Study Suggests During Sleep, Neural Process Helps Clear the Brain of Damaging Waste

Posted on by Dr. Monica M. Bertagnolli

We’ve long known that sleep is a restorative process necessary for good health. Research has also shown that the accumulation of waste products in the brain is a leading cause of numerous neurological disorders, including Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases. What hasn’t been clear is how the healthy brain “self-cleans,” or flushes out that detrimental waste.

But a new study by a research team supported in part by NIH suggests that a neural process that happens while we sleep helps cleanse the brain, leading us to wake up feeling rested and restored. Better understanding this process could one day lead to methods that help people function well on less sleep. It could also help researchers find potential ways to delay or prevent neurological diseases related to accumulated waste products in the brain.

The findings, reported in Nature, show that, during sleep, neural networks in the brain act like an array of miniature pumps, producing large and rhythmic waves through synchronous bursts of activity that propel fluids through brain tissue. Much like the process of washing dishes, where you use a rhythmic motion of varying speeds and intensity to clear off debris, this process that takes place during sleep clears accumulated metabolic waste products out.

The research team, led by Jonathan Kipnis and Li-Feng Jiang-Xie at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, wanted to better understand how the brain manages its waste. This is not an easy task, given that the human brain’s billions of neurons inevitably produce plenty of junk during cognitive processes that allow us to think, feel, move, and solve problems. Those waste products also build in a complex environment, including a packed maze of interconnected neurons, blood vessels, and interstitial spaces, surrounded by a protective blood-brain barrier that limits movement of substances in or out.

So, how does the brain move fluid through those tight spaces with the force required to get waste out? Earlier research suggested that neural activity during sleep might play an important role in those waste-clearing dynamics. But previous studies hadn’t pinned down the way this works.

To learn more in the new study, the researchers recorded brain activity in mice. They also used an ultrathin silicon probe to measure fluid dynamics in the brain’s interstitial spaces. In awake mice, they saw irregular neural activity and only minor fluctuations in the interstitial spaces. But when the animals were resting under anesthesia, the researchers saw a big change. Brain recordings showed strongly enhanced neural activity, with two distinct but tightly coupled rhythms. The research team realized that the structured wave patterns could generate strong energy that could move small molecules and peptides, or waste products, through the tight spaces within brain tissue.

To make sure that the fluid dynamics were really driven by neurons, the researchers used tools that allowed them to turn neural activity off in some areas. Those experiments showed that, when neurons stopped firing, the waves also stopped. They went on to show similar dynamics during natural sleep in the animals and confirmed that disrupting these neuron-driven fluid dynamics impaired the brain’s ability to clear out waste.

These findings highlight the importance of this cleansing process during sleep for brain health. The researchers now want to better understand how specific patterns and variations in those brain waves lead to changes in fluid movement and waste clearance. This could help researchers eventually find ways to speed up the removal of damaging waste, potentially preventing or delaying certain neurological diseases and allowing people to need less sleep.

Reference:

[1] Jiang-Xie LF, et al. Neuronal dynamics direct cerebrospinal fluid perfusion and brain clearance. Nature. DOI: 10.1038/s41586-024-07108-6 (2024).

NIH Support: National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health

Aided by AI, Study Uncovers Hidden Sex Differences in Dynamic Brain Function

Posted on by Dr. Monica M. Bertagnolli

We’re living in an especially promising time for biomedical discovery and advances in the delivery of data-driven health care for everyone. A key part of this is the tremendous progress made in applying artificial intelligence to study human health and ultimately improve clinical care in many important and sometimes surprising ways.1 One new example of this comes from a fascinating study, supported in part by NIH, that uses AI approaches to reveal meaningful sex differences in the way the brain works.

As reported in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, researchers led by Vinod Menon at Stanford Medicine, Stanford, CA, have built an AI model that can—nine times out of ten—tell whether the brain in question belongs to a female or male based on scans of brain activity alone.2 These findings not only help resolve long-term debates about whether reliable differences between sexes exist in the human brain, but they’re also a step toward improving our understanding of why some psychiatric and neurological disorders affect women and men differently.

The prevalence of certain psychiatric and neurological disorders in men and women can vary significantly, leading researchers to suspect that sex differences in brain function likely exist. For example, studies have found that females are more likely to experience depression, anxiety, and eating disorders, while autism, Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder, and schizophrenia are seen more often in males. But earlier research to understand sex differences in the brain have focused mainly on anatomical and structural studies of brain regions and their connections. Much less is known about how those structural differences translate into differences in brain activity and function.

To help fill those gaps in the new study, Menon’s team took advantage of vast quantities of brain activity data from MRI scans from the NIH-supported Human Connectome Project. The data was captured from hundreds of healthy young adults with the goal of studying the brain and how it changes with growth, aging, and disease. To use this data to explore sex differences in brain function, the researchers developed what’s known as a deep neural network model in which a computer “learned” how to recognize patterns in brain activity data that could distinguish a male from a female brain.

This approach doesn’t rely on any preconceived notions about what features might be important. A computer is simply shown many examples of brain activity belonging to males and females and, over time, can begin to pick up on otherwise hidden differences that are useful for making such classifications accurately. One of the things that made this work different from earlier attempts was it relied on dynamic scans of brain activity, which capture the interplay among brain regions.

After analyzing about 1,500 brain scans, a computer could usually (although not always) tell whether a scan came from a male or female brain. The findings also showed the model worked reliably well in different datasets and in brain scans for people in different places in the U.S. and Europe. Overall, the findings confirm that reliable sex differences in brain activity do exist.

Where did the model find those differences? To get an idea, the researchers turned to an approach called explainable AI, which allowed them to dig deeper into the specific features and brain areas their model was using to pick up on sex differences. It turned out that one set of areas the model was relying on to distinguish between male and female brains is what’s known as the default mode network. This area is responsible for processing self-referential information and constructing a coherent sense of the self and activates especially when people let their minds wander.3 Other important areas included the striatum and limbic network, which are involved in learning and how we respond to rewards, respectively.

Many questions remain, including whether such differences arise primarily due to inherent biological differences between the sexes or what role societal circumstances play. But the researchers say that the discovery already shows that sex differences in brain organization and function may play important and overlooked roles in mental health and neuropsychiatric disorders. Their AI model can now also be applied to begin to explain other kinds of brain differences, including those that may affect learning or social behavior. It’s an exciting example of AI-driven progress and good news for understanding variations in human brain functions and their implications for our health.

References:

[1] Bertagnolli, MM. Advancing health through artificial intelligence/machine learning: The critical importance of multidisciplinary collaboration. PNAS Nexus. DOI: 10.1093/pnasnexus/pgad356 (2023).

[2] Ryali S, et al. Deep learning models reveal replicable, generalizable, and behaviorally relevant sex differences in human functional brain organization. Proc Natl Acad Sci. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2310012121 (2024).

[3] Menon, V. 20 years of the default mode network: A review and synthesis. Neuron.DOI: 10.1016/j.neuron.2023.04.023 (2023).

NIH Support: National Institute of Mental Health, National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering, Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Institute on Aging

New Findings in Football Players May Aid the Future Diagnosis and Study of Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE)

Posted on by Dr. Monica M. Bertagnolli

Repeated hits to the head—whether from boxing, playing American football or experiencing other repetitive head injuries—can increase someone’s risk of developing a serious neurodegenerative condition called chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE). Unfortunately, CTE can only be diagnosed definitively after death during an autopsy of the brain, making it a challenging condition to study and treat. The condition is characterized by tau protein building up in the brain and causes a wide range of problems in thinking, understanding, impulse control, and more. Recent NIH-funded research shows that, alarmingly, even young, amateur players of contact and collision sports can have CTE, underscoring the urgency of finding ways to understand, diagnose, and treat CTE.1

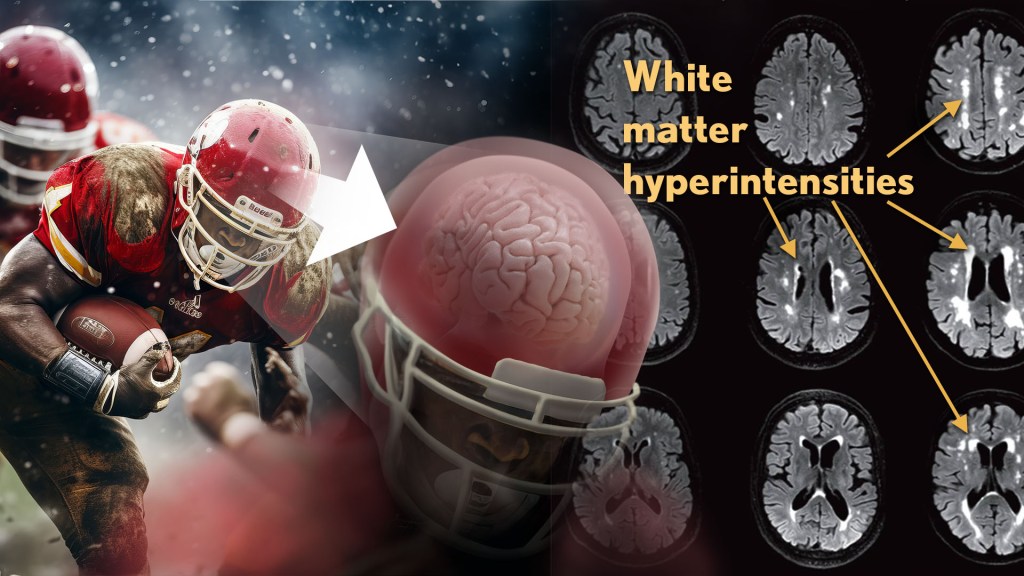

New findings published in the journal Neurology show that increased presence of certain brain lesions that are visible on MRI scans may be related to other brain changes in former football players. The study describes a new way to capture and analyze the long-term impacts of repeated head injuries, which could have implications for understanding signs of CTE. 2

The study analyzes data from the Diagnose CTE Research Project, an NIH-supported effort to develop methods for diagnosing CTE during life and to examine other potential risk factors for the degenerative brain condition. It involves 120 former professional football players and 60 former college football players with an average age of 57. For comparison, it also includes 60 men with an average age of 59 who had no symptoms, did not play football, and had no history of head trauma or concussion.

The new findings link some of the downstream risks of repetitive head impacts to injuries in white matter, the brain’s deeper tissue. Known as white matter hyperintensities (WMH), these injuries show up on MRI scans as easy-to-see bright spots.

Earlier studies had shown that athletes who had experienced repetitive head impacts had an unusual amount of WMH on their brain scans. Those markers, which also show up more as people age normally, are associated with an increased risk for stroke, cognitive decline, dementia and death. In the new study, researchers including Michael Alosco, Boston University Chobanian & Avedisian School of Medicine, wanted to learn more about WMH and their relationship to other signs of brain trouble seen in former football players.

All the study’s volunteers had brain scans and lumbar punctures to collect cerebrospinal fluid in search of underlying signs or biomarkers of neurodegenerative disease and white matter changes. In the former football players, the researchers found more evidence of WMH. As expected, those with an elevated burden of WMH were more likely to have more risk factors for stroke—such as high blood pressure, hypertension, high cholesterol, and diabetes—but this association was 11 times stronger in former football players than in non-football players. More WMH was also associated with increased concentrations of tau protein in cerebrospinal fluid, and this connection was twice as strong in the football players vs. non-football players. Other signs of functional breakdown in the brain’s white matter were more apparent in participants with increased WMH, and this connection was nearly quadrupled in the former football players.

These latest results don’t prove that WMH from repetitive head impacts cause the other troubling brain changes seen in football players or others who go on to develop CTE. But they do highlight an intriguing association that may aid the further study and diagnosis of repetitive head impacts and CTE, with potentially important implications for understanding—and perhaps ultimately averting—their long-term consequences for brain health.

References:

[1] AC McKee, et al. Neuropathologic and Clinical Findings in Young Contact Sport Athletes Exposed to Repetitive Head Impacts. JAMA Neurology. DOI:10.1001/jamaneurol.2023.2907 (2023).

[2] MT Ly, et al. Association of Vascular Risk Factors and CSF and Imaging Biomarkers With White Matter Hyperintensities in Former American Football Players. Neurology. DOI: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000208030 (2024).

NIH Support: National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, National Institute on Aging and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences

Experiencing the Neural Symphony Underlying Memory through a Blend of Science and Art

Posted on by John Ngai, PhD, NIH BRAIN Initiative

Ever wonder how you’re able to remember life events that happened days, months, or even years ago? You have your hippocampus to thank. This essential area in the brain relies on intense and highly synchronized patterns of activity that aren’t found anywhere else in the brain. They’re called “sharp-wave ripples.”

These dynamic ripples have been likened to the brain version of an instant replay, appearing most commonly during rest after a notable experience. And, now, the top video winner in this year’s Brain Research Through Advancing Innovative Neurotechnologies® (BRAIN) Initiative’s annual Show Us Your BRAINs! Photo and Video Contest allows you to witness the “chatter” that those ripples set off in other neurons. The details of this chatter determine just how durable a particular memory is in ways neuroscientists are still working hard to understand.

Neuroscientist Saman Abbaspoor in the lab of Kari Hoffman at Vanderbilt University, Nashville, in collaboration with Tyler Sloan from the Montreal-based Quorumetrix Studio, sets the stage in the winning video by showing an electrode or probe implanted in the brain that can reach the hippocampus. This device allows the Hoffman team to wirelessly record neural activity in different layers of the hippocampus as the animal either rests or moves freely about.

In the scenes that follow, neurons (blue, cyan, and yellow) flash on and off. The colors highlight the fact that this brain area and the neurons within it aren’t all the same. Various types of neurons are found in the brain area’s different layers, some of which spark the activity you see, while others dampen it.

Hoffman explains that the specific shapes of individual cells pictured are realistic but also symbolic. While they didn’t trace the individual branches of neurons in the brain in their studies, they relied on information from previous anatomical studies, overlaying their intricate forms with flashing bursts of activity that come straight from their recorded data.

Sloan then added yet another layer of artistry to the experience with what he refers to as sonification, or the use of music to convey information about the dynamic and coordinated bursts of activity in those cells. At five seconds in, you hear the subtle flutter of a sharp-wave ripple. With each burst of active neural chatter that follows, you hear the dramatic plink of piano keys.

Together, their winning video creates a unique sensory experience that helps to explain what goes on during memory formation and recall in a way that words alone can’t adequately describe. Through their ongoing studies, Hoffman reports that they’ll continue delving even deeper into understanding these intricate dynamics and their implications for learning and memory. Ultimately, they also want to explore how brain ripples, and the neural chatter they set off, might be enhanced to make memory formation and recall even stronger.

References:

S Abbaspoor & KL Hoffman. State-dependent circuit dynamics of superficial and deep CA1 pyramidal cells in macaques. BioRxiv DOI: 10.1101/2023.12.06.570369 (2023). Please note that this article is a pre-print and has not been peer-reviewed.

NIH Support: The NIH BRAIN Initiative

This article was updated on Dec. 15, 2023 to reflect better the collaboration on the project among Abbaspoor, Hoffman and Sloan.

The Amazing Brain: Turning Conventional Wisdom on Brain Anatomy on its Head

Posted on by John Ngai, PhD, NIH BRAIN Initiative

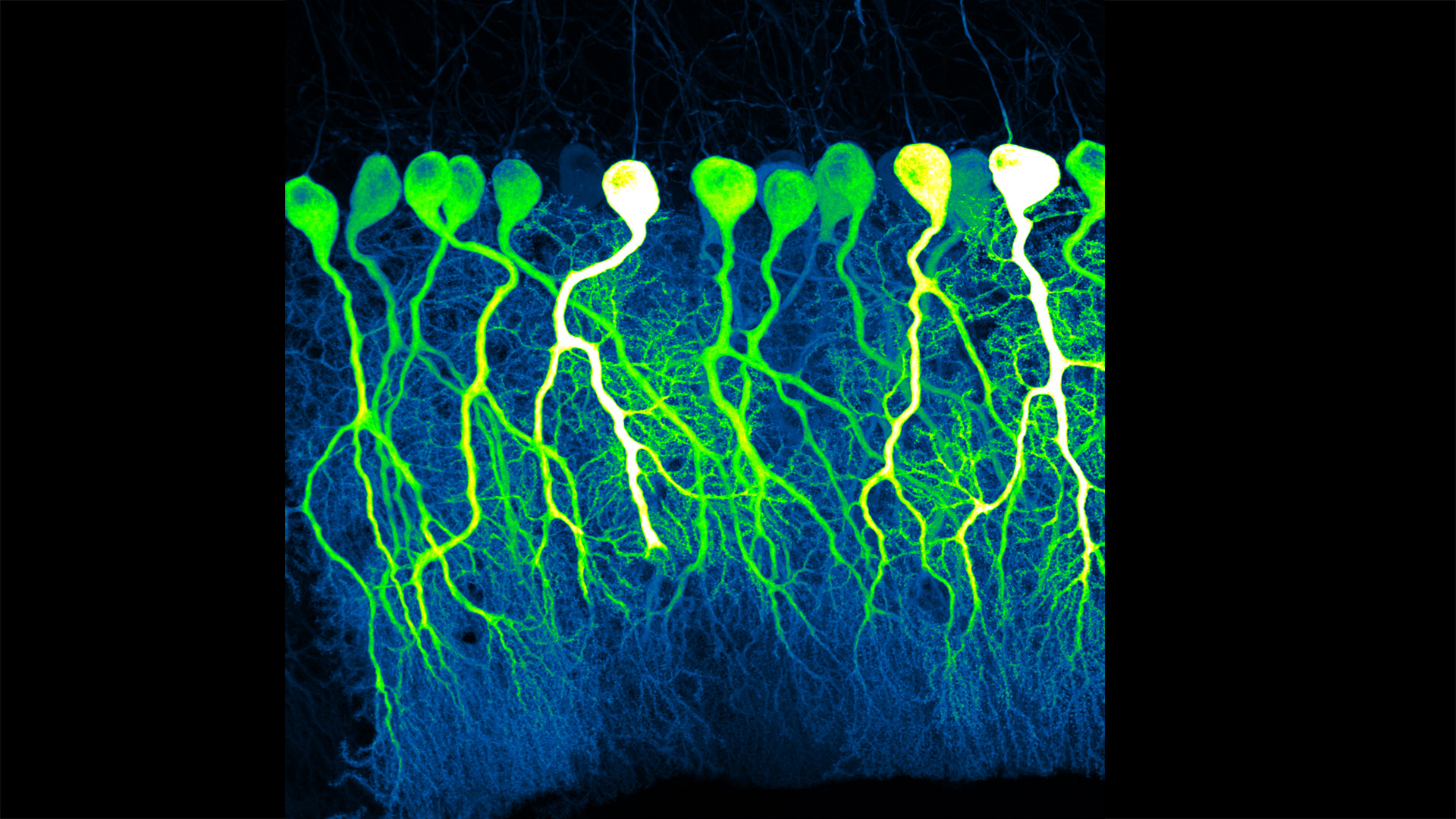

Silas Busch at the University of Chicago captured this slightly eerie scene, noting it reminded him of people shuffling through the dark of night. What you’re really seeing are some of the largest neurons in the mammalian brain, known as Purkinje cells. The photo won first place this year in the Brain Research through Advancing Innovative Neurotechnologies® (BRAIN) Initiative’s annual Show Us Your BRAINs! Photo and Video Contest.

While humans have them, too, the Purkinje cells pictured here are in the brain of a mouse. The head-like shapes you see in the image are the so-called soma, or the neurons’ cell bodies. Extending downwards are the heavily branched dendrites, which act like large antennae, receiving thousands of inputs from the rest of the body.

One reason this picture is such a standout, explains Busch, is because of what you don’t see. You’ll notice that only a few cells are fluorescently labeled and therefore lit up in green, leaving the rest in shadows. As a result, it’s possible to trace the detailed branches of individual Purkinje cells and make out their intricate forms. As it turns out, this ability to trace Purkinje cells so precisely led Busch, who is a graduate student in Christian Hansel’s lab focused on the neurobiology of learning and memory, to a surprising discovery, which the pair recently reported in Science.1

Purkinje cells connect to nerve fibers that “climb up” from the brain stem, which connects your brain and spinal cord to help control breathing, heart rate, balance and more. Scientists thought that each Purkinje cell received only one of these climbing fibers from the brain stem on its single primary branch.

However, after carefully tracing thousands of Purkinje cells in brain tissue from both mice and humans, the researchers have now shown that Purkinje cells and climbing fibers don’t always have a simple one-to-one relationship. In fact, Busch and Hansel found more than 95 percent of human Purkinje cells have multiple primary branches, not just one. In mice, that ratio is closer to 50 percent.

The researchers went on to show that mouse Purkinje cells with multiple primary branches often also receive multiple climbing fibers. The discovery rewrites the textbook idea of how Purkinje cells in the brain and climbing fibers from the brainstem are anatomically arranged.

Not surprisingly, those extra connections in the cerebellum (located in the back of the brain) also have important functional implications. When Purkinje cells have just one climbing fiber input, the new study shows, the whole cell receives each signal equally and responds accordingly. But, in cells with multiple climbing fiber inputs, the researchers could detect differences across a single cell depending on which primary branch received an input.

What this means is that Purkinje cells in the brain have much more computational power than had been appreciated. That extra brain power has important implications for understanding how brain circuits can adapt and respond to changes outside the body that now warrant further study. The new findings may have implications also for understanding the role of these Purkinje cell connections in some neurological and developmental disorders, including autism2 and a movement disorder known as cerebellar ataxia.

As they say, a picture is worth a thousand words. And this winning image comes as a reminder that we still have more to learn from careful study of basic brain anatomy, with important implications for human health and disease.

References:

[1] SE Busch and C Hansel. Climbing fiber multi-innervation of mouse Purkinje dendrites with arborization common to human. Science. DOI: 10.1126/science.adi1024. (2023).

[2] DH Simmons et al. Sensory Over-responsivity and Aberrant Plasticity in Cerebellar Cortex in a Mouse Model of Syndromic Autism. Biological Psychiatry: Global Open Science. DOI: 10.1016/j.bpsgos.2021.09.004. (2021).

Brain Atlas Paves the Way for New Understanding of How the Brain Functions

Posted on by Lawrence Tabak, D.D.S., Ph.D.

When NIH launched The BRAIN Initiative® a decade ago, one of many ambitious goals was to develop innovative technologies for profiling single cells to create an open-access reference atlas cataloguing the human brain’s many parts. The ultimate goal wasn’t to produce a single, static reference map, but rather to capture a dynamic view of how the brain’s many cells of varied types are wired to work together in the healthy brain and how this picture may shift in those with neurological and mental health disorders.

So I’m now thrilled to report the publication of an impressive collection of work from hundreds of scientists in the BRAIN Initiative Cell Census Network (BICCN), detailed in more than 20 papers in Science, Science Advances, and Science Translational Medicine.1 Among many revelations, this unprecedented, international effort has characterized more than 3,000 human brain cell types. To put this into some perspective, consider that the human lung contains 61 cell types.2 The work has also begun to uncover normal variation in the brains of individual people, some of the features that distinguish various disease states, and distinctions among key parts of the human brain and those of our closely related primate cousins.

Of course, it’s not possible to do justice to this remarkable body of work or its many implications in the space of a single blog post. But to give you an idea of what’s been accomplished, some of these studies detail the primary effort to produce a comprehensive brain atlas, including defining the brain’s many cell types along with their underlying gene activity and the chemical modifications that turn gene activity up or down.3,4,5

Other studies in this collection take a deep dive into more specific brain areas. For instance, to capture normal variations among people, a team including Nelson Johansen, University of California, Davis, profiled cells in the neocortex—the outermost portion of the brain that’s responsible for many complex human behaviors.6 Overall, the work revealed a highly consistent cellular makeup from one person to the next. But it also highlighted considerable variation in gene activity, some of which could be explained by differences in age, sex and health. However, much of the observed variation remains unexplained, opening the door to more investigations to understand the meaning behind such brain differences and their role in making each of us who we are.

Yang Li, now at Washington University in St. Louis, and his colleagues analyzed 1.1 million cells from 42 distinct brain areas in samples from three adults.4 They explored various cell types with potentially important roles in neuropsychiatric disorders and were able to pinpoint specific cell types, genes and genetic switches that may contribute to the development of certain traits and disorders, including bipolar disorder, depression and schizophrenia.

Yet another report by Nikolas Jorstad, Allen Institute, Seattle, and colleagues delves into essential questions about what makes us human as compared to other primates like chimpanzees.7 Their comparisons of gene activity at the single-cell level in a specific area of the brain show that humans and other primates have largely the same brain cell types, but genes are activated differently in specific cell types in humans as compared to other primates. Those differentially expressed genes in humans often were found in portions of the genome that show evidence of rapid change over evolutionary time, suggesting that they play important roles in human brain function in ways that have yet to be fully explained.

All the data represented in this work has been made publicly accessible online for further study. Meanwhile, the effort to build a more finely detailed picture of even more brain cell types and, with it, a more complete understanding of human brain circuitry and how it can go awry continues in the BRAIN Initiative Cell Atlas Network (BICAN). As impressive as this latest installment is—in our quest to understand the human brain, brain disorders, and their treatment—we have much to look forward to in the years ahead.

References:

A list of all the papers part of the brain atlas research is available here: https://www.science.org/collections/brain-cell-census.

[1] M Maroso. A quest into the human brain. Science DOI: 10.1126/science.adl0913 (2023).

[2] L Sikkema, et al. An integrated cell atlas of the lung in health and disease. Nature Medicine DOI: 10.1038/s41591-023-02327-2 (2023).

[3] K Siletti, et al. Transcriptomic diversity of cell types across the adult human brain. Science DOI: 10.1126/science.add7046 (2023).

[4] Y Li, et al. A comparative atlas of single-cell chromatin accessibility in the human brain. Science DOI: 10.1126/science.adf7044 (2023).

[5] W Tian, et al. Single-cell DNA methylation and 3D genome architecture in the human brain. Science DOI: 10.1126/science.adf5357 (2023).

[6] N Johansen, et al. Interindividual variation in human cortical cell type abundance and expression. Science DOI: 10.1126/science.adf2359 (2023).

[7] NL Jorstad, et al. Comparative transcriptomics reveals human-specific cortical features. Science DOI: 10.1126/science.ade9516 (2023).

NIH Support: Projects funded through the NIH BRAIN Initiative Cell Consensus Network

Taking a Deep Dive into the Alzheimer’s Brain in Search of Understanding and New Targets

Posted on by Lawrence Tabak, D.D.S., Ph.D.

People living with Alzheimer’s disease experience a gradual erosion of memory and thinking skills until they can no longer carry out daily activities. Hallmarks of the disease include the buildup of plaques that collect between neurons, accumulations of tau protein inside neurons and weakening of neural connections. However, there’s still much to learn about what precisely happens in the Alzheimer’s brain and how the disorder’s devastating march might be slowed or even stopped. Alzheimer’s affects more than six million people in the United States and is the seventh leading cause of death among adults in the U.S., according to the National Institute on Aging.

NIH-supported researchers recently published a trove of data in the journal Cell detailing the molecular drivers of Alzheimer’s disease and which cell types in the brain are most likely to be affected.1,2,3,4 The scientists, led by Li-Huei Tsai and Manolis Kellis, both at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA, characterized gene activity at the single-cell level in more than two million cells from postmortem brain tissue. They also assessed DNA damage and surveyed epigenetic changes in cells, which refers to chemical modifications to DNA that alter gene expression in the cell. The findings could help researchers pinpoint new targets for Alzheimer’s disease treatments.

In the first of four studies, the researchers examined 54 brain cell types in 427 brain samples from a cohort of people with varying levels of cognitive impairment that has been followed since 1994.1 The MIT team generated an atlas of gene activity patterns within the brain’s prefrontal cortex, an important area for memory retrieval.

Their analyses in brain samples taken from people with Alzheimer’s dementia showed altered activity in genes involved in various functions. Additional findings showed that people with normal cognitive abilities with evidence of plaques in their brains had more neurons that inhibit or dampen activity in the prefrontal cortex compared to those with Alzheimer’s dementia. The finding suggests that the workings of inhibitory neurons may play an unexpectedly important role in maintaining cognitive resilience despite age-related changes, including the buildup of plaques. It’s one among many discoveries that now warrant further study.

In another report, the researchers compared brain tissues from 48 people without Alzheimer’s to 44 people with early- or late-stage Alzheimer’s.2 They developed a map of the various elements that regulate function within cells in the prefrontal cortex. By cross-referencing epigenomic and gene activity data, the researchers showed changes in many genes with known links to Alzheimer’s disease development and risk.

Their single-cell analysis also showed that these changes most often occur in microglia, which are immune cells that remove cellular waste products from the brain. At the same time, every cell type they studied showed a breakdown over time in the cells’ normal epigenomic patterning, a process that may cause a cell to behave differently as it loses essential aspects of its original identity and function.

In a third report, the researchers looked even deeper into gene activity within the brain’s waste-clearing microglia.3 Based on the activity of hundreds of genes, they were able to define a dozen distinct microglia “states.” They also showed that more microglia enter an inflammatory state in the Alzheimer’s brain compared to a healthy human brain. Fewer microglia in the Alzheimer’s brain were in a healthy, balanced state as well. The findings suggest that treatments that target microglia to reduce inflammation and promote balance may hold promise for treating Alzheimer’s disease.

The fourth and final report zeroed in on DNA damage, inspired in part by earlier findings suggesting greater damage within neurons even before Alzheimer’s symptoms appear.4 In fact, breaks in DNA occur as part of the normal process of forming new memories. But those breaks in the healthy brain are quickly repaired as the brain makes new connections.

The researchers studied postmortem brain tissue samples and found that, over time in the Alzheimer’s brain, the damage exceeds the brain’s ability to repair it. As a result, attempts to put the DNA back together leads to a patchwork of mistakes, including rearrangements in the DNA and fusions as separate genes are merged. Such changes appear to arise especially in genes that control neural connections, which may contribute to the signs and symptoms of Alzheimer’s.

The researchers say they now plan to apply artificial intelligence and other analytic tools to learn even more about Alzheimer’s disease from this trove of data. To speed progress even more, they’ve made all the data freely available online to the research community, where it promises to yield many more fundamentally important discoveries about the precise underpinnings of Alzheimer’s disease in the brain and new ways to intervene in Alzheimer’s dementia.

References:

[1] Mathys H, et al. Single-cell atlas reveals correlates of high cognitive function, dementia, and resilience to Alzheimer’s disease pathology. Cell. DOI: 10.1016/j.cell.2023.08.039. (2023).

[2] Xiong X, et al. Epigenomic dissection of Alzheimer’s disease pinpoints causal variants and reveals epigenome erosion. Cell. DOI: 10.1016/j.cell.2023.08.040. (2023).

[3] Sun N, et al. Human microglial state dynamics in Alzheimer’s disease progression. Cell. DOIi: 10.1016/j.cell.2023.08.037. (2023).

[4] Dileep V, et al. Neuronal DNA double-strand breaks lead to genome structural variations and 3D genome disruption in neurodegeneration. Cell. 2023 DOI: 10.1016/j.cell.2023.08.038. (2023).

NIH Support: National Institute on Aging, National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, National Institute of Mental Health, National Institute of General Medical Sciences

Next Page