chromatin

Brain Atlas Paves the Way for New Understanding of How the Brain Functions

Posted on by Lawrence Tabak, D.D.S., Ph.D.

When NIH launched The BRAIN Initiative® a decade ago, one of many ambitious goals was to develop innovative technologies for profiling single cells to create an open-access reference atlas cataloguing the human brain’s many parts. The ultimate goal wasn’t to produce a single, static reference map, but rather to capture a dynamic view of how the brain’s many cells of varied types are wired to work together in the healthy brain and how this picture may shift in those with neurological and mental health disorders.

So I’m now thrilled to report the publication of an impressive collection of work from hundreds of scientists in the BRAIN Initiative Cell Census Network (BICCN), detailed in more than 20 papers in Science, Science Advances, and Science Translational Medicine.1 Among many revelations, this unprecedented, international effort has characterized more than 3,000 human brain cell types. To put this into some perspective, consider that the human lung contains 61 cell types.2 The work has also begun to uncover normal variation in the brains of individual people, some of the features that distinguish various disease states, and distinctions among key parts of the human brain and those of our closely related primate cousins.

Of course, it’s not possible to do justice to this remarkable body of work or its many implications in the space of a single blog post. But to give you an idea of what’s been accomplished, some of these studies detail the primary effort to produce a comprehensive brain atlas, including defining the brain’s many cell types along with their underlying gene activity and the chemical modifications that turn gene activity up or down.3,4,5

Other studies in this collection take a deep dive into more specific brain areas. For instance, to capture normal variations among people, a team including Nelson Johansen, University of California, Davis, profiled cells in the neocortex—the outermost portion of the brain that’s responsible for many complex human behaviors.6 Overall, the work revealed a highly consistent cellular makeup from one person to the next. But it also highlighted considerable variation in gene activity, some of which could be explained by differences in age, sex and health. However, much of the observed variation remains unexplained, opening the door to more investigations to understand the meaning behind such brain differences and their role in making each of us who we are.

Yang Li, now at Washington University in St. Louis, and his colleagues analyzed 1.1 million cells from 42 distinct brain areas in samples from three adults.4 They explored various cell types with potentially important roles in neuropsychiatric disorders and were able to pinpoint specific cell types, genes and genetic switches that may contribute to the development of certain traits and disorders, including bipolar disorder, depression and schizophrenia.

Yet another report by Nikolas Jorstad, Allen Institute, Seattle, and colleagues delves into essential questions about what makes us human as compared to other primates like chimpanzees.7 Their comparisons of gene activity at the single-cell level in a specific area of the brain show that humans and other primates have largely the same brain cell types, but genes are activated differently in specific cell types in humans as compared to other primates. Those differentially expressed genes in humans often were found in portions of the genome that show evidence of rapid change over evolutionary time, suggesting that they play important roles in human brain function in ways that have yet to be fully explained.

All the data represented in this work has been made publicly accessible online for further study. Meanwhile, the effort to build a more finely detailed picture of even more brain cell types and, with it, a more complete understanding of human brain circuitry and how it can go awry continues in the BRAIN Initiative Cell Atlas Network (BICAN). As impressive as this latest installment is—in our quest to understand the human brain, brain disorders, and their treatment—we have much to look forward to in the years ahead.

References:

A list of all the papers part of the brain atlas research is available here: https://www.science.org/collections/brain-cell-census.

[1] M Maroso. A quest into the human brain. Science DOI: 10.1126/science.adl0913 (2023).

[2] L Sikkema, et al. An integrated cell atlas of the lung in health and disease. Nature Medicine DOI: 10.1038/s41591-023-02327-2 (2023).

[3] K Siletti, et al. Transcriptomic diversity of cell types across the adult human brain. Science DOI: 10.1126/science.add7046 (2023).

[4] Y Li, et al. A comparative atlas of single-cell chromatin accessibility in the human brain. Science DOI: 10.1126/science.adf7044 (2023).

[5] W Tian, et al. Single-cell DNA methylation and 3D genome architecture in the human brain. Science DOI: 10.1126/science.adf5357 (2023).

[6] N Johansen, et al. Interindividual variation in human cortical cell type abundance and expression. Science DOI: 10.1126/science.adf2359 (2023).

[7] NL Jorstad, et al. Comparative transcriptomics reveals human-specific cortical features. Science DOI: 10.1126/science.ade9516 (2023).

NIH Support: Projects funded through the NIH BRAIN Initiative Cell Consensus Network

First Comprehensive Census of Cell Types in Brain Area Controlling Movement

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

The primary motor cortex is the part of the brain that enables most of our skilled movements, whether it’s walking, texting on our phones, strumming a guitar, or even spiking a volleyball. The region remains a major research focus, and that’s why NIH’s Brain Research Through Advancing Innovative Neurotechnologies® (BRAIN) Initiative – Cell Census Network (BICCN) has just unveiled two groundbreaking resources: a complete census of cell types present in the mammalian primary motor cortex, along with the first detailed atlas of the region, located along the back of the frontal lobe in humans (purple stripe above).

This remarkably comprehensive work, detailed in a flagship paper and more than a dozen associated articles published in the journal Nature, promises to vastly expand our understanding of the primary motor cortex and how it works to keep us moving [1]. The papers also represent the collaborative efforts of more than 250 BICCN scientists from around the world, teaming up over many years.

Started in 2013, the BRAIN Initiative is an ambitious project with a range of groundbreaking goals, including the creation of an open-access reference atlas that catalogues all of the brain’s many billions of cells. The primary motor cortex was one of the best places to get started on assembling an atlas because it is known to be well conserved across mammalian species, from mouse to human. There’s also a rich body of work to aid understanding of more precise cell-type information.

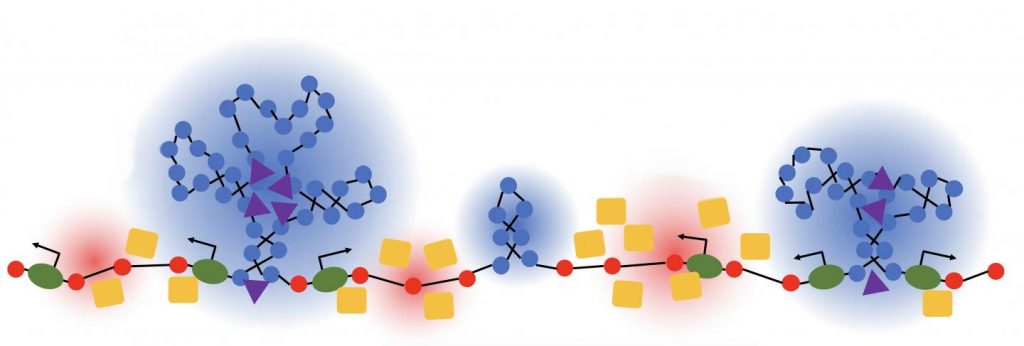

Taking advantage of recent technological advances in single-cell analysis, the researchers categorized into different types the millions of neurons and other cells in this brain region. They did so on the basis of morphology, or shape, of the cells, as well as their locations and connections to other cells. The researchers went even further to characterize and sort cells based on: their complex patterns of gene expression, the presence or absence of chemical (or epigenetic) marks on their DNA, the way their chromosomes are packaged into chromatin, and their electrical properties.

The new data and analyses offer compelling evidence that neural cells do indeed fall into distinct types, with a high degree of correspondence across their molecular genetic, anatomical, and physiological features. These findings support the notion that neural cells can be classified into molecularly defined types that are also highly conserved or shared across mammalian species.

So, how many cell types are there? While that’s an obvious question, it doesn’t have an easy answer. The number varies depending upon the method used for sorting them. The researchers report that they have identified about 25 classes of cells, including 16 different neuronal classes and nine non-neuronal classes, each composed of multiple subtypes of cells.

These 25 classes were determined by their genetic profiles, their locations, and other characteristics. They also showed up consistently across species and using different experimental approaches, suggesting that they have important roles in the neural circuitry and function of the motor cortex in mammals.

Still, many precise features of the cells don’t fall neatly into these categories. In fact, by focusing on gene expression within single cells of the motor cortex, the researchers identified more potentially important cell subtypes, which fall into roughly 100 different clusters, or distinct groups. As scientists continue to examine this brain region and others using the latest new methods and approaches, it’s likely that the precise number of recognized cell types will continue to grow and evolve a bit.

This resource will now serve as a springboard for future research into the structure and function of the brain, both within and across species. The datasets already have been organized and made publicly available for scientists around the world.

The atlas also now provides a foundation for more in-depth study of cell types in other parts of the mammalian brain. The BICCN is already engaged in an effort to generate a brain-wide cell atlas in the mouse, and is working to expand coverage in the atlas for other parts of the human brain.

The cell census and atlas of the primary motor cortex are important scientific advances with major implications for medicine. Strokes commonly affect this region of the brain, leading to partial or complete paralysis of the opposite side of the body.

By considering how well cell census information aligns across species, scientists also can make more informed choices about the best models to use for deepening our understanding of brain disorders. Ultimately, these efforts and others underway will help to enable precise targeting of specific cell types and to treat a wide range of brain disorders that affect thinking, memory, mood, and movement.

Reference:

[1] A multimodal cell census and atlas of the mammalian primary motor cortex. BRAIN Initiative Cell Census Network (BICCN). Nature. Oct 6, 2021.

Links:

NIH Brain Research Through Advancing Innovative Neurotechnologies® (BRAIN) Initiative (NIH)

BRAIN Initiative – Cell Census Network (BICCN) (NIH)

NIH Support: National Institute of Mental Health; National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke

A New View of the 3D Genome

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

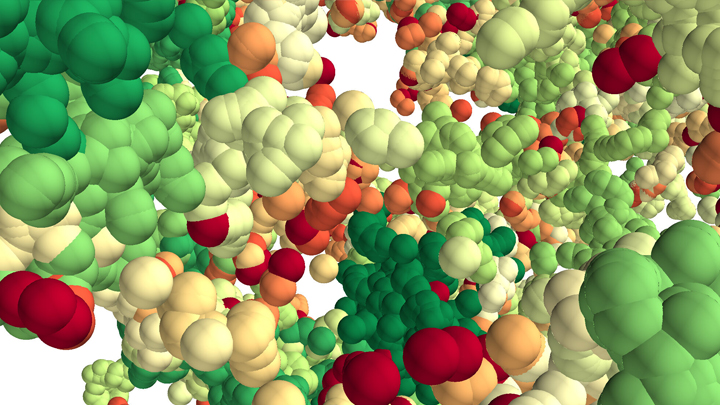

This lush panoply of color might stir up daydreams of getting away to explore a tropical rain forest. But what you see here is a new model that’s enabling researchers to explore something equally amazing: how a string of DNA that measures 6 feet long can be packed into the microscopic nucleus of a human cell. Fitting that much DNA in a nucleus is like fitting a thread the length of the Empire State building underneath your fingernail!

Scientists have known for a while that that the answer lies in how DNA is folded onto spool-like complexes called chromatin, but many details of the process still remain to be worked out. Recently, an NIH-funded team, led by Vadim Backman and Igal Szleifer, Northwestern University, Evanston, IL, developed this new model of chromatin folding by pairing sophisticated mathematical modeling and optical imaging.In a study published in the journal Science Advances [1], the team found that chromatin is folded into a variety of tree-like domains along a chromatin backbone, which they liken to an aggregation of trees growing from the forest floor. The colorful spheres you see above represent trees of varying sizes.

Earlier models of chromatin folding had suggested that DNA folds into regular and orderly fibers. In the new study, the Northwestern researchers used their own specially designed Partial Wave Spectroscopic microscope. This high-powered system, coupled with electron imaging, allowed them to peer deep inside living cells to “sense” real-time alterations in chromatin packing. What makes their new view on chromatin so interesting is it suggests our DNA is packaged in a way that’s much more disorderly and unpredictable than initially thought.

As Backman notes, it is reasonable to assume that a forest would be filled with trees of varying sizes and shapes. But you couldn’t predict the exact location of each tree or its particular size and configuration. The same appears to be true of these tree-like structures within chromatin. Their precise location and size vary, seemingly unpredictably, from cell to cell.

This apparently random DNA packing structure might seem surprising given chromatin’s importance in influencing the expression and function of our genes. But the researchers think such variability likely has its advantages.

Here’s the idea: If all of our cells responded to stressful conditions (such as heat or a toxic exposure) in exactly the same way and that way happened to be suboptimal, the whole tissue or organ might fail. But if differences in chromatin structure lead each cell to respond somewhat differently to the same stimulus, then some cells might be more likely to survive or even thrive under the stress. It’s a built-in way for cells to hedge their bets.

These new findings offer a fundamentally new three-dimensional view of the human genome. They might also inspire innovative strategies to understand and fight cancer, as well as other diseases. And, while most of us probably won’t be venturing off into the rain forest anytime soon, this work does give us all something to think about next time we’re enjoying the great outdoors in our own neck of the woods.

Reference:

[1] Physical and data structure of 3D genome. Huang K, Li Y, Shim AR, Virk RKA, Agrawal V, Eshein A, Nap RJ, Almassalha LM, Backman V, Szleifer I. Sci Adv. 2020 Jan 10;6(2):eaay4055.

Links:

Deoxyribonucleic Acid (DNA) (National Human Genome Research Institute/NIH)

4D Nucleome (Common Fund/NIH)

Vadim Backman (Northwestern University, Evanston, IL)

Igal Szleifer (Northwestern University, Evanston, IL)

NIH Support: National Cancer Institute

Building a 3D Map of the Genome

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

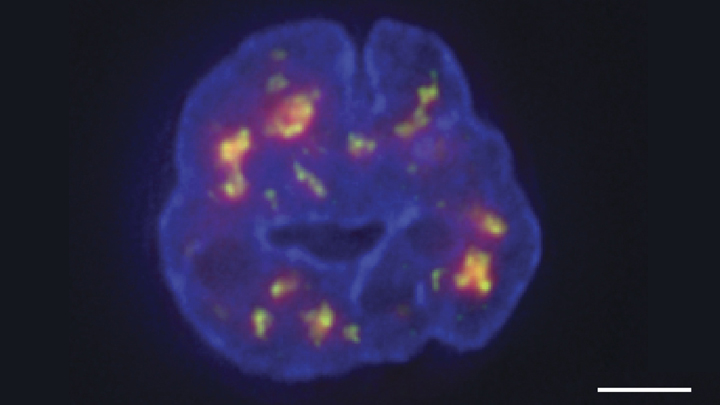

Credit: Chen et al., 2018

Researchers have learned a lot in recent years about how six-plus feet of human DNA gets carefully packed into a tiny cell nucleus that measures less than .00024 of an inch. Under those cramped conditions, we’ve been learning more and more about how DNA twists, turns, and spatially orients its thousands of genes within the nucleus and what this positioning might mean for health and disease.

Thanks to a new technique developed by an NIH-funded research team, there is now an even more refined view [1]. The image above features the nucleus (blue) of a human leukemia cell. The diffuse orange-red clouds highlight chemically labeled DNA found in close proximity to the tiny nuclear speckles (green). You’ll need to look real carefully to see the nuclear speckles, but these structural landmarks in the nucleus have long been thought to serve as storage sites for important cellular machinery.

Creative Minds: A New Way to Look at Cancer

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Inside our cells, strands of DNA wrap around spool-like histone proteins to form a DNA-histone complex called chromatin. Bradley Bernstein, a pathologist at Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard University, and Broad Institute, has always been fascinated by this process. What interests him is the fact that an approximately 6-foot-long strand of DNA can be folded and packed into orderly chromatin structures inside a cell nucleus that’s just 0.0002 inch wide.

Bernstein’s fascination with DNA packaging led to the recent major discovery that, when chromatin misfolds in brain cells, it can activate a gene associated with the cancer glioma [1]. This suggested a new cancer-causing mechanism that does not require specific DNA mutations. Now, with a 2016 NIH Director’s Pioneer Award, Bernstein is taking a closer look at how misfolded and unstable chromatin can drive tumor formation, and what that means for treating cancer.

Creative Minds: Studying the Human Genome in 3D

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

As a kid, Jesse Dixon often listened to his parents at the dinner table discussing how to run experiments and their own research laboratories. His father Jack is an internationally renowned biochemist and the former vice president and chief scientific officer of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. His mother Claudia Kent Dixon, now retired, did groundbreaking work in the study of lipid molecules that serve as the building blocks of cell membranes.

So, when Jesse Dixon set out to pursue a career, he followed in his parents’ footsteps and chose science. But Dixon, a researcher at the Salk Institute, La Jolla, CA, has charted a different research path by studying genomics, with a focus on understanding chromosomal structure. Dixon has now received a 2016 NIH Director’s Early Independence Award to study the three-dimensional organization of the genome, and how changes in its structure might contribute to diseases such as cancer or even to physical differences among people.