stroke

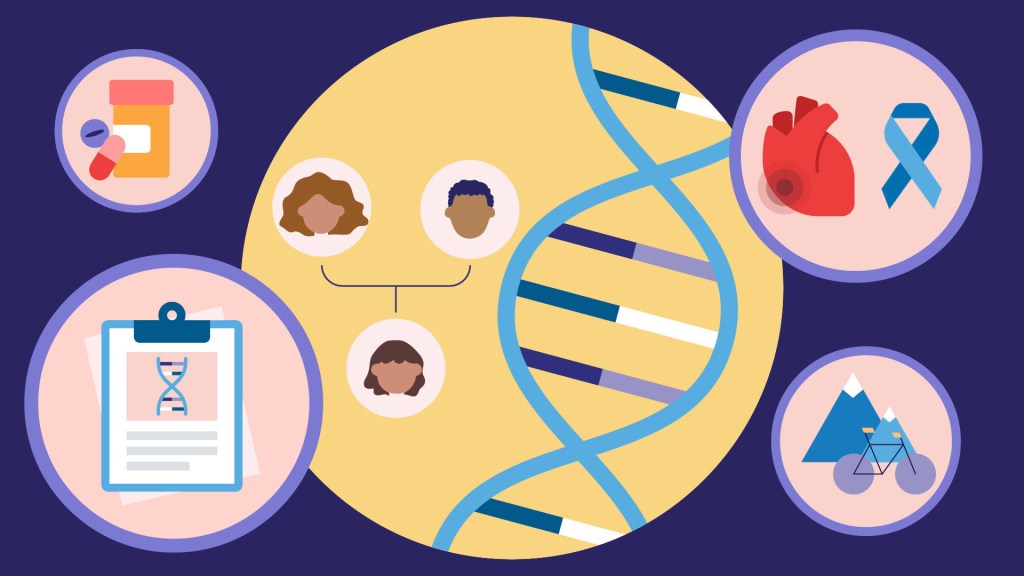

All of Us Research Program Participants Fuel Both Scientific and Personal Discovery

Posted on by Josh Denny, M.D., M.S., All of Us Research Program

The NIH’s All of Us Research Program is a historic effort to create an unprecedented research resource that will speed biomedical breakthroughs, transform medicine and advance health equity. To create this resource, we are enrolling at least 1 million people who reflect the diversity of the United States.

At the program’s outset, we promised to make research a two-way street by returning health information to our participant partners. We are now delivering on that promise. We are returning personalized health-related DNA reports to participants who choose to receive them.

That includes me. I signed up to receive my “Medicine and Your DNA” and “Hereditary Disease Risk” reports along with nearly 200,000 other participant partners. I recently read my results, and they hit home, revealing an eye-opening connection between my personal and professional lives.

First, the professional. Before coming to All of Us, I was a practicing physician and researcher at Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN, where I studied how a person’s genes might affect his or her response to medications. One of the drug-gene interactions that I found most interesting is related to clopidogrel, a drug commonly prescribed to keep arteries open after a major cardiovascular event, like a heart attack, stroke, or placement of a stent.

People with certain gene variations are not able to process this medication well, leaving them in a potentially risky situation. The patient and their health care provider may think the condition is being managed. But, since they can’t process the medication, the patient’s symptoms and risks are likely to increase.

The impact on patients has been seen in numerous studies, including one that I published with colleagues last year in the Journal of Stroke and Cerebrovascular Disease [1]. We found that stroke risk is three times higher in patients who were poor responders to clopidogrel and treated with the drug following a “mini-stroke”—also known as a transient ischemic attack. Other studies have shown that major cardiovascular events were 50 percent more common in individuals who were poor responders to clopidogrel [2]. Importantly, there are alternative therapies that work well for people with this genetic variant.

Now, the personal. Reading my health-related results, I learned that I carry some of these very same gene variations. So, if I ever needed a medicine to manage my risk of blood clots, clopidogrel would not likely work well for me.

Instead, should I ever need treatment, my provider and I could bypass this common first-line therapy and choose an alternate medicine. Getting the right treatment on the first try could cut my chances of a heart attack in half. The benefits of this knowledge don’t stop with me. By choosing to share my findings with family members who may have inherited the same genetic variations, they can discuss it with their health care teams.

Other program participants who choose to receive results will experience the same process of learning more about their health. Nearly all will get actionable information about how their body may process certain medications. A small percentage, 2 to 3 percent, may learn they’re at higher risk of developing several severe hereditary health conditions, such as certain preventable heart diseases and cancers. The program will provide a genetic counselor at no cost to all participants to discuss their results.

To enroll participants who reflect the country’s diverse population, All of Us partners with trusted community organizations around the country. Inclusion is vitally important in the field of genomics research, where available data have long originated mostly from people of European ancestry. In contrast, about 50 percent of the All of Us’ genomic data come from individuals who self-identify with a racial or ethnic minority group.

More than 3,600 research projects are already underway using data contributed by participants from diverse backgrounds. What’s especially exciting about this “ecosystem” of discovery between participants and researchers is that, by contributing their data, participants are helping researchers decode what our DNA is telling us about health across all types of conditions. In turn, those discoveries will deepen what participants can learn.

Those who have stepped up to join All of Us are the heartbeat of this historic research effort to advance personalized approaches in medicine. Their contributions are already fueling new discoveries in numerous areas of health.

At the same time, making good on our promises to our participant partners ensures that the knowledge gained doesn’t only accumulate in a database but is delivered back to participants to help advance their own health journeys. If you’re interested in joining All of Us, we welcome you to learn more.

References:

[1] CYP2C19 loss-of-function is associated with increased risk of ischemic stroke after transient ischemic attack in intracranial atherosclerotic disease. Patel PD, Vimalathas P, Niu X, Shannon CN, Denny JC, Peterson JF, Chitale RV, Fusco MR. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2021 Feb;30(2):105464.

[2] Predicting clopidogrel response using DNA samples linked to an electronic health record. Delaney JT, Ramirez AH, Bowton E, Pulley JM, Basford MA, Schildcrout JS, Shi Y, Zink R, Oetjens M, Xu H, Cleator JH, Jahangir E, Ritchie MD, Masys DR, Roden DM, Crawford DC, Denny JC. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2012 Feb;91(2):257-263.

Links:

Join All of Us (All of Us/NIH)

NIH’s All of Us Research Program returns genetic health-related results to participants, NIH News Release, December 13, 2022.

NIH’s All of Us Research Program Releases First Genomic Dataset of Nearly 100,000 Whole Genome Sequences, NIH News Release, March 17, 2022.

Funding and Program Partners (All of Us)

Medicine and Your DNA (All of Us)

Clopidogrel Response (National Library of Medicine/NIH)

Hereditary Disease Risk (All of Us)

Preparing for DNA Results: What Is a Genetic Counselor? (All of Us)

Research Projects Directory (All of Us)

Note: Dr. Lawrence Tabak, who performs the duties of the NIH Director, has asked the heads of NIH’s Institutes, Centers, and Offices to contribute occasional guest posts to the blog to highlight some of the interesting science that they support and conduct. This is the 24th in the series of NIH guest posts that will run until a new permanent NIH director is in place.

To Prevent a Stroke, Household Chores and Leisurely Strolls May Help

Posted on by Lawrence Tabak, D.D.S., Ph.D.

As we get older, unfortunately our chances of having a stroke rise. While there’s obviously no way to turn back the clock on our age, fortunately there are ways to lower our risk of a stroke and that includes staying physically active. Take walks, ride a bike, play a favorite sport. According to our current exercise guidelines for American adults, the goal is to get in at least two and a half hours each week of moderate-intensity physical activity as well as two days of muscle-strengthening activity [1].

But a new study, published in the journal JAMA Network Open, shows that reducing the chances of a stroke as we get older doesn’t necessarily require heavy aerobic exercise or a sweat suit [2]. For those who are less mobile or less interested in getting out to exercise, the researchers discovered that just spending time doing light-intensity physical activity—such as tending to household chores—“significantly” protects against stroke.

The study also found you don’t have to dedicate whole afternoons to tidying up around the house to protect your health. It helps to just get up out of your chair for five or 10 minutes at a time throughout the day to straighten up a room, sweep the floor, fold the laundry, step outside to water the garden, or just take a leisurely stroll.

That may sound simple, but consider that the average American adult now spends on average six and a half hours per day just sitting [3]. That comes to nearly two days per week on average, much to the detriment of our health and wellbeing. Indeed, the study found that middle-aged and older people who were sedentary for 13 hours or more hours per day had a 44 percent increased risk of stroke.

These latest findings come from Steven Hooker, San Diego State University, CA, and his colleagues on the NIH-supported Reasons for Geographic and Racial Differences in Stroke (REGARDS) study. Launched in 2003, REGARDS continues to follow over time more than 30,000 Black and white participants aged 45 and older.

Hooker and colleagues wanted to know more about the amount and intensity of exercise required to prevent a stroke. Interestingly, the existing data were relatively weak, in part because prior studies looking at the associations between physical activity and stroke risk relied on self-reported data, which don’t allow for precise measures. What’s more, the relationship between time spent sitting and stroke risk also remained unknown.

To get answers, Hooker and team focused on 7,607 adults enrolled in the REGARDS study. Rather than relying on self-reported physical activity data, team members asked participants to wear a hip-mounted accelerometer—a device that records how fast people move—during waking hours for seven days between May 2009 and January 2013.

The average age of participants was 63. Men and women were represented about equally in the study, while about 70 percent of participants were white and 30 percent were Black.

Over the more than seven years of the study, 286 participants suffered a stroke. The researchers then analyzed all the accelerometer data, including the amount and intensity of their physical activity over the course of a normal week. They then related those data to their risk of having a stroke over the course of the study.

The researchers found, as anticipated, that adults who spent the most time doing moderate-to-vigorous intensity physical activity were less likely to have a stroke than those who spent the least time physically active. But those who spent the most time sitting also were at greater stroke risk, whether they got their weekly exercise in or not.

Those who regularly sat still for longer periods—17 minutes or more at a time—had a 54 percent increase in stroke risk compared to those who more often sat still for less than eight minutes. After adjusting for the time participants spent sitting, those who more often had shorter periods of moderate-to-vigorous activity—less than 10 minutes at a time—still had significantly lower stroke risk. But, once the amount of time spent sitting was taken into account, longer periods of more vigorous activity didn’t make a difference.

While high blood pressure, diabetes, and myriad other factors also contribute to a person’s cumulative risk of stroke, the highlighted paper does bring some good actionable news. For each hour spent doing light-intensity physical activity instead of sitting, a person can reduce his or her stroke risk.

The bad news, of course, is that each extra hour spent sitting per day comes with an increased risk for stroke. This bad news shouldn’t be taken lightly. In the U.S., almost 800,000 people have a stroke each year. That’s one person every 40 seconds with, on average, one death every four minutes. Globally, stroke is the second most common cause of death and third most common cause of disability in people, killing more than 6.5 million each year.

If you’re already meeting the current exercise guidelines for adults, keep up the good work. If not, this paper shows you can still do something to lower your stroke risk. Make a habit throughout the day of getting up out of your chair for a mere five or 10 minutes to straighten up a room, sweep the floor, fold the laundry, step outside to water the garden, or take a leisurely stroll. It could make a big difference to your health as you age.

References:

[1] How much physical activity do adults need? Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. June 2, 2022.

[2] Association of accelerometer-measured sedentary time and physical activity with risk of stroke among US adults. Hooker SP, Diaz KM, Blair SN, Colabianchi N, Hutto B, McDonnell MN, Vena JE, Howard VJ. JAMA Netw Open. 2022 Jun 1;5(6):e2215385.

[3] Trends in sedentary behavior among the US population, 2001-2016. Yang L, Cao C, Kantor ED, Nguyen LH, Zheng X, Park Y, Giovannucci EL, Matthews CE, Colditz GA, Cao Y. JAMA. 2019 Apr 23;321(16):1587-1597.

Links:

Stroke (National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke/NIH)

REGARDS Study (University of Alabama at Birmingham)

NIH Support: National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke; National Institute on Aging

First Comprehensive Census of Cell Types in Brain Area Controlling Movement

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

The primary motor cortex is the part of the brain that enables most of our skilled movements, whether it’s walking, texting on our phones, strumming a guitar, or even spiking a volleyball. The region remains a major research focus, and that’s why NIH’s Brain Research Through Advancing Innovative Neurotechnologies® (BRAIN) Initiative – Cell Census Network (BICCN) has just unveiled two groundbreaking resources: a complete census of cell types present in the mammalian primary motor cortex, along with the first detailed atlas of the region, located along the back of the frontal lobe in humans (purple stripe above).

This remarkably comprehensive work, detailed in a flagship paper and more than a dozen associated articles published in the journal Nature, promises to vastly expand our understanding of the primary motor cortex and how it works to keep us moving [1]. The papers also represent the collaborative efforts of more than 250 BICCN scientists from around the world, teaming up over many years.

Started in 2013, the BRAIN Initiative is an ambitious project with a range of groundbreaking goals, including the creation of an open-access reference atlas that catalogues all of the brain’s many billions of cells. The primary motor cortex was one of the best places to get started on assembling an atlas because it is known to be well conserved across mammalian species, from mouse to human. There’s also a rich body of work to aid understanding of more precise cell-type information.

Taking advantage of recent technological advances in single-cell analysis, the researchers categorized into different types the millions of neurons and other cells in this brain region. They did so on the basis of morphology, or shape, of the cells, as well as their locations and connections to other cells. The researchers went even further to characterize and sort cells based on: their complex patterns of gene expression, the presence or absence of chemical (or epigenetic) marks on their DNA, the way their chromosomes are packaged into chromatin, and their electrical properties.

The new data and analyses offer compelling evidence that neural cells do indeed fall into distinct types, with a high degree of correspondence across their molecular genetic, anatomical, and physiological features. These findings support the notion that neural cells can be classified into molecularly defined types that are also highly conserved or shared across mammalian species.

So, how many cell types are there? While that’s an obvious question, it doesn’t have an easy answer. The number varies depending upon the method used for sorting them. The researchers report that they have identified about 25 classes of cells, including 16 different neuronal classes and nine non-neuronal classes, each composed of multiple subtypes of cells.

These 25 classes were determined by their genetic profiles, their locations, and other characteristics. They also showed up consistently across species and using different experimental approaches, suggesting that they have important roles in the neural circuitry and function of the motor cortex in mammals.

Still, many precise features of the cells don’t fall neatly into these categories. In fact, by focusing on gene expression within single cells of the motor cortex, the researchers identified more potentially important cell subtypes, which fall into roughly 100 different clusters, or distinct groups. As scientists continue to examine this brain region and others using the latest new methods and approaches, it’s likely that the precise number of recognized cell types will continue to grow and evolve a bit.

This resource will now serve as a springboard for future research into the structure and function of the brain, both within and across species. The datasets already have been organized and made publicly available for scientists around the world.

The atlas also now provides a foundation for more in-depth study of cell types in other parts of the mammalian brain. The BICCN is already engaged in an effort to generate a brain-wide cell atlas in the mouse, and is working to expand coverage in the atlas for other parts of the human brain.

The cell census and atlas of the primary motor cortex are important scientific advances with major implications for medicine. Strokes commonly affect this region of the brain, leading to partial or complete paralysis of the opposite side of the body.

By considering how well cell census information aligns across species, scientists also can make more informed choices about the best models to use for deepening our understanding of brain disorders. Ultimately, these efforts and others underway will help to enable precise targeting of specific cell types and to treat a wide range of brain disorders that affect thinking, memory, mood, and movement.

Reference:

[1] A multimodal cell census and atlas of the mammalian primary motor cortex. BRAIN Initiative Cell Census Network (BICCN). Nature. Oct 6, 2021.

Links:

NIH Brain Research Through Advancing Innovative Neurotechnologies® (BRAIN) Initiative (NIH)

BRAIN Initiative – Cell Census Network (BICCN) (NIH)

NIH Support: National Institute of Mental Health; National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke

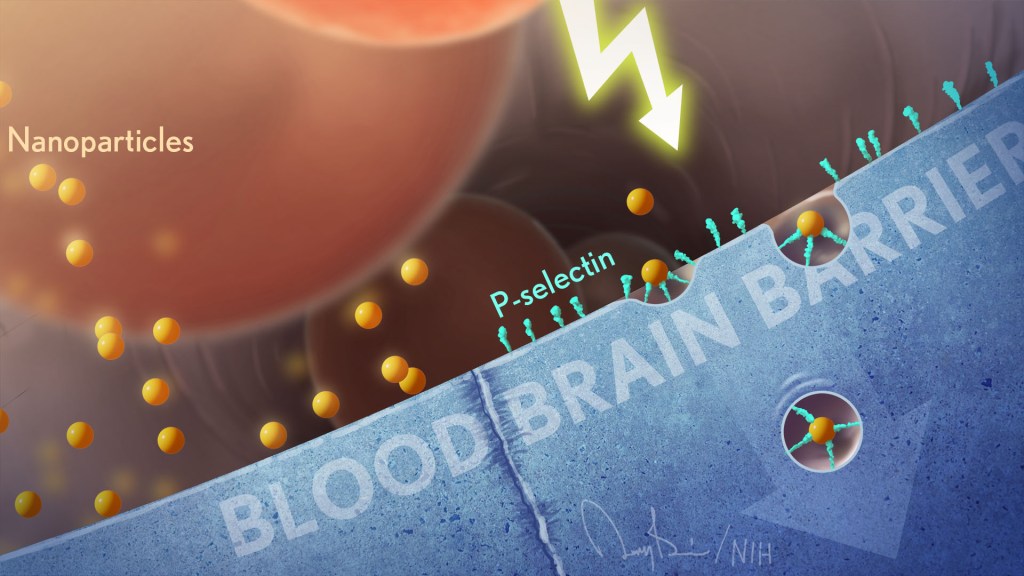

Gene Therapy Shows Promise Repairing Brain Tissue Damaged by Stroke

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

It’s a race against time when someone suffers a stroke caused by a blockage of a blood vessel supplying the brain. Unless clot-busting treatment is given within a few hours after symptoms appear, vast numbers of the brain’s neurons die, often leading to paralysis or other disabilities. It would be great to have a way to replace those lost neurons. Thanks to gene therapy, some encouraging strides are now being made.

In a recent study in Molecular Therapy, researchers reported that, in their mouse and rat models of ischemic stroke, gene therapy could actually convert the brain’s support cells into new, fully functional neurons [1]. Even better, after gaining the new neurons, the animals had improved motor and memory skills.

For the team led by Gong Chen, Penn State, University Park, the quest to replace lost neurons in the brain began about a decade ago. While searching for the right approach, Chen noticed other groups had learned to reprogram fibroblasts into stem cells and make replacement neural cells.

As innovative as this work was at the time, it was performed mostly in lab Petri dishes. Chen and his colleagues thought, why not reprogram cells already in the brain?

They turned their attention to the brain’s billions of supportive glial cells. Unlike neurons, glial cells divide and replicate. They also are known to survive and activate following a brain injury, remaining at the wound and ultimately forming a scar. This same process had also been observed in the brain following many types of injury, including stroke and neurodegenerative conditions such as Alzheimer’s disease.

To Chen’s NIH-supported team, it looked like glial cells might be a perfect target for gene therapies to replace lost neurons. As reported about five years ago, the researchers were on the right track [2].

The Chen team showed it was possible to reprogram glial cells in the brain into functional neurons. They succeeded using a genetically engineered retrovirus that delivered a single protein called NeuroD1. It’s a neural transcription factor that switches genes on and off in neural cells and helps to determine their cell fate. The newly generated neurons were also capable of integrating into brain circuits to repair damaged tissue.

There was one major hitch: the NeuroD1 retroviral vector only reprogrammed actively dividing glial cells. That suggested their strategy likely couldn’t generate the large numbers of new cells needed to repair damaged brain tissue following a stroke.

Fast-forward a couple of years, and improved adeno-associated viral vectors (AAV) have emerged as a major alternative to retroviruses for gene therapy applications. This was exactly the breakthrough that the Chen team needed. The AAVs can reprogram glial cells whether they are dividing or not.

In the new study, Chen’s team, led by post-doc Yu-Chen Chen, put this new gene therapy system to work, and the results are quite remarkable. In a mouse model of ischemic stroke, the researchers showed the treatment could regenerate about a third of the total lost neurons by preferentially targeting reactive, scar-forming glial cells. The conversion of those reactive glial cells into neurons also protected another third of the neurons from injury.

Studies in brain slices showed that the replacement neurons were fully functional and appeared to have made the needed neural connections in the brain. Importantly, their studies also showed that the NeuroD1 gene therapy led to marked improvements in the functional recovery of the mice after a stroke.

In fact, several tests of their ability to make fine movements with their forelimbs showed about a 60 percent improvement within 20 to 60 days of receiving the NeuroD1 therapy. Together with study collaborator and NIH grantee Gregory Quirk, University of Puerto Rico, San Juan, they went on to show similar improvements in the ability of rats to recover from stroke-related deficits in memory.

While further study is needed, the findings in rodents offer encouraging evidence that treatments to repair the brain after a stroke or other injury may be on the horizon. In the meantime, the best strategy for limiting the number of neurons lost due to stroke is to recognize the signs and get to a well-equipped hospital or call 911 right away if you or a loved one experience them. Those signs include: sudden numbness or weakness of one side of the body; confusion; difficulty speaking, seeing, or walking; and a sudden, severe headache with unknown causes. Getting treatment for this kind of “brain attack” within four hours of the onset of symptoms can make all the difference in recovery.

References:

[1] A NeuroD1 AAV-Based gene therapy for functional brain repair after ischemic injury through in vivo astrocyte-to-neuron conversion. Chen Y-C et al. Molecular Therapy. Published online September 6, 2019.

[2] In vivo direct reprogramming of reactive glial cells into functional neurons after brain injury and in an Alzheimer’s disease model. Guo Z, Zhang L, Wu Z, Chen Y, Wang F, Chen G. Cell Stem Cell. 2014 Feb 6;14(2):188-202.

Links:

Stroke (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute/NIH)

Gene Therapy (National Human Genome Research Institute/NIH)

Chen Lab (Penn State, University Park)

NIH Support: National Institute on Aging; National Institute of Mental Health

New Grants Explore Benefits of Music on Health

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

It’s not every day you get to perform with one of the finest voices on the planet. What an honor it was to join renowned opera singer Renée Fleming back in May for a rendition of “How Can I Keep from Singing?” at the NIH’s J. Edward Rall Cultural Lecture. Yet our duet was so much more. Between the song’s timeless message and Renée’s matchless soprano, the music filled me with a profound sense of joy, like being briefly lifted outside myself into a place of beauty and well-being. How does that happen?

Indeed, the benefits of music for human health and well-being have long been recognized. But biomedical science still has a quite limited understanding of music’s mechanisms of action in the brain, as well as its potential to ease symptoms of an array of disorders including Parkinson’s disease, stroke, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). In a major step toward using rigorous science to realize music’s potential for improving human health, NIH has just awarded $20 million over five years to support the first research projects of the Sound Health initiative. Launched a couple of years ago, Sound Health is a partnership between NIH and the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts, in association with the National Endowment for the Arts.

With support from 10 NIH institutes and centers, the Sound Health awardees will, among other things, study how music might improve the motor skills of people with Parkinson’s disease. Previous research has shown that the beat of a metronome can steady the gait of someone with Parkinson’s disease, but more research is needed to determine exactly why that happens.

Other fascinating areas to be explored by the Sound Health awardees include:

• Assessing how active music interventions, often called music therapies, affect multiple biomarkers that correlate with improvement in health status. The aim is to provide a more holistic understanding of how such interventions serve to ease cancer-related stress and possibly even improve immune function.

• Investigating the effects of music on the developing brain of infants as they learn to talk. Such work may be especially helpful for youngsters at high risk for speech and language disorders.

• Studying synchronization of musical rhythm as part of social development. This research will look at how this process is disrupted in children with autism spectrum disorder, possibly suggesting ways of developing music-based interventions to improve communication.

• Examining the memory-related impacts of repeated exposures to a certain song or musical phrase, including those “earworms” that get “stuck” in our heads. This work might tell us more about how music sometimes serves as a cue for retrieving associated memories, even in people whose memory skills are impaired by Alzheimer’s disease or other cognitive disorders.

• Tracing the developmental timeline—from childhood to adulthood—of how music shapes the brain. This will include studying how musical training at different points on that timeline may influence attention span, executive function, social/emotional functioning, and language skills.

We are fortunate to live in an exceptional time of discovery in neuroscience, as well as an extraordinary era of creativity in music. These Sound Health grants represent just the beginning of what I hope will be a long and productive partnership that brings these creative fields together. I am convinced that the power of science holds tremendous promise for improving the effectiveness of music-based interventions, and expanding their reach to improve the health and well-being of people suffering from a wide variety of conditions.

Links:

The Soprano and the Scientist: A Conversation About Music and Medicine, (National Public Radio, June 2, 2017)

NIH Workshop on Music and Health, January 2017

Sound Health (NIH)

NIH Support: National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health; National Eye Institute; National Institute on Aging; National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders; National Institute of Mental Health; National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke; National Institute of Nursing Research; Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences Research; Office of the Director

Can a Mind-Reading Computer Speak for Those Who Cannot?

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Credit: Adapted from Nima Mesgarani, Columbia University’s Zuckerman Institute, New York

Computers have learned to do some amazing things, from beating the world’s ranking chess masters to providing the equivalent of feeling in prosthetic limbs. Now, as heard in this brief audio clip counting from zero to nine, an NIH-supported team has combined innovative speech synthesis technology and artificial intelligence to teach a computer to read a person’s thoughts and translate them into intelligible speech.

Turning brain waves into speech isn’t just fascinating science. It might also prove life changing for people who have lost the ability to speak from conditions such as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) or a debilitating stroke.

When people speak or even think about talking, their brains fire off distinctive, but previously poorly decoded, patterns of neural activity. Nima Mesgarani and his team at Columbia University’s Zuckerman Institute, New York, wanted to learn how to decode this neural activity.

Mesgarani and his team started out with a vocoder, a voice synthesizer that produces sounds based on an analysis of speech. It’s the very same technology used by Amazon’s Alexa, Apple’s Siri, or other similar devices to listen and respond appropriately to everyday commands.

As reported in Scientific Reports, the first task was to train a vocoder to produce synthesized sounds in response to brain waves instead of speech [1]. To do it, Mesgarani teamed up with neurosurgeon Ashesh Mehta, Hofstra Northwell School of Medicine, Manhasset, NY, who frequently performs brain mapping in people with epilepsy to pinpoint the sources of seizures before performing surgery to remove them.

In five patients already undergoing brain mapping, the researchers monitored activity in the auditory cortex, where the brain processes sound. The patients listened to recordings of short stories read by four speakers. In the first test, eight different sentences were repeated multiple times. In the next test, participants heard four new speakers repeat numbers from zero to nine.

From these exercises, the researchers reconstructed the words that people heard from their brain activity alone. Then the researchers tried various methods to reproduce intelligible speech from the recorded brain activity. They found it worked best to combine the vocoder technology with a form of computer artificial intelligence known as deep learning.

Deep learning is inspired by how our own brain’s neural networks process information, learning to focus on some details but not others. In deep learning, computers look for patterns in data. As they begin to “see” complex relationships, some connections in the network are strengthened while others are weakened.

In this case, the researchers used the deep learning networks to interpret the sounds produced by the vocoder in response to the brain activity patterns. When the vocoder-produced sounds were processed and “cleaned up” by those neural networks, it made the reconstructed sounds easier for a listener to understand as recognizable words, though this first attempt still sounds pretty robotic.

The researchers will continue testing their system with more complicated words and sentences. They also want to run the same tests on brain activity, comparing what happens when a person speaks or just imagines speaking. They ultimately envision an implant, similar to those already worn by some patients with epilepsy, that will translate a person’s thoughts into spoken words. That might open up all sorts of awkward moments if some of those thoughts weren’t intended for transmission!

Along with recently highlighted new ways to catch irregular heartbeats and cervical cancers, it’s yet another remarkable example of the many ways in which computers and artificial intelligence promise to transform the future of medicine.

Reference:

[1] Towards reconstructing intelligible speech from the human auditory cortex. Akbari H, Khalighinejad B, Herrero JL, Mehta AD, Mesgarani N. Sci Rep. 2019 Jan 29;9(1):874.

Links:

Advances in Neuroprosthetic Learning and Control. Carmena JM. PLoS Biol. 2013;11(5):e1001561.

Nima Mesgarani (Columbia University, New York)

NIH Support: National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders; National Institute of Mental Health

Skin Cells Can Be Reprogrammed In Vivo

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Thousands of Americans are rushed to the hospital each day with traumatic injuries. Daniel Gallego-Perez hopes that small chips similar to the one that he’s touching with a metal stylus in this photo will one day be a part of their recovery process.

The chip, about one square centimeter in size, includes an array of tiny channels with the potential to regenerate damaged tissue in people. Gallego-Perez, a researcher at The Ohio State University Colleges of Medicine and Engineering, Columbus, has received a 2018 NIH Director’s New Innovator Award to develop the chip to reprogram skin and other cells to become other types of tissue needed for healing. The reprogrammed cells then could regenerate and restore injured neural or vascular tissue right where it’s needed.

Gallego-Perez and his Ohio State colleagues wondered if it was possible to engineer a device placed on the skin that’s capable of delivering reprogramming factors directly into cells, eliminating the need for the viral delivery vectors now used in such work. While such a goal might sound futuristic, Gallego-Perez and colleagues offered proof-of-principle last year in Nature Nanotechnology that such a chip can reprogram skin cells in mice. [1]

Here’s how it works: First, the chip’s channels are loaded with specific reprogramming factors, including DNA or proteins, and then the chip is placed on the skin. A small electrical current zaps the chip’s channels, driving reprogramming factors through cell membranes and into cells. The process, called tissue nanotransfection (TNT), is finished in milliseconds.

To see if the chips could help heal injuries, researchers used them to reprogram skin cells into vascular cells in mice. Not only did the technology regenerate blood vessels and restore blood flow to injured legs, the animals regained use of those limbs within two weeks of treatment.

The researchers then went on to show that they could use the chips to reprogram mouse skin cells into neural tissue. When proteins secreted by those reprogrammed skin cells were injected into mice with brain injuries, it helped them recover.

In the newly funded work, Gallego-Perez wants to take the approach one step further. His team will use the chip to reprogram harder-to-reach tissues within the body, including peripheral nerves and the brain. The hope is that the device will reprogram cells surrounding an injury, even including scar tissue, and “repurpose” them to encourage nerve repair and regeneration. Such an approach may help people who’ve suffered a stroke or traumatic nerve injury.

If all goes well, this TNT method could one day fill an important niche in emergency medicine. Gallego-Perez’s work is also a fine example of just one of the many amazing ideas now being pursued in the emerging field of regenerative medicine.

Reference:

[1] Topical tissue nano-transfection mediates non-viral stroma reprogramming and rescue. Gallego-Perez D, Pal D, Ghatak S, Malkoc V, Higuita-Castro N, Gnyawali S, Chang L, Liao WC, Shi J, Sinha M, Singh K, Steen E, Sunyecz A, Stewart R, Moore J, Ziebro T, Northcutt RG, Homsy M, Bertani P, Lu W, Roy S, Khanna S, Rink C, Sundaresan VB, Otero JJ, Lee LJ, Sen CK. Nat Nanotechnol. 2017 Oct;12(10):974-979.

Links:

Stroke Information (National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke/NIH)

Burns and Traumatic Injury (NIH)

Peripheral Neuropathy (National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke/NIH)

Video: Breakthrough Device Heals Organs with a Single Touch (YouTube)

Gallego-Perez Lab (The Ohio State University College of Medicine, Columbus)

Gallego-Perez Project Information (NIH RePORTER)

NIH Support: Common Fund; National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke

Next Page