memory

An Inflammatory View of Early Alzheimer’s Disease

Posted on by Lawrence Tabak, D.D.S., Ph.D.

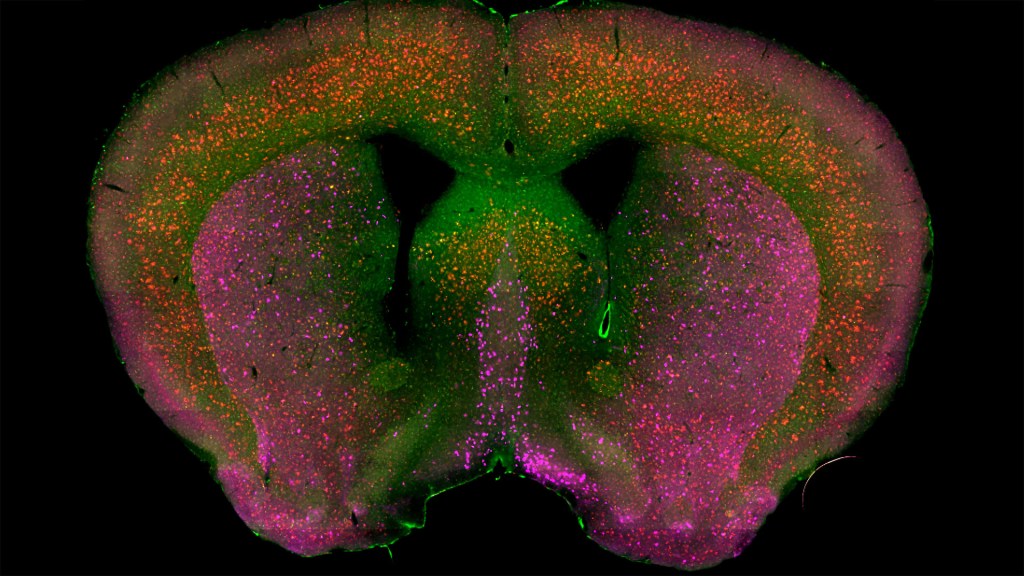

Detecting the earliest signs of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) in middle-aged people and tracking its progression over time in research studies continue to be challenging. But it is easier to do in shorter-lived mammalian models of AD, especially when paired with cutting-edge imaging tools that look across different regions of the brain. These tools can help basic researchers detect telltale early changes that might point the way to better prevention or treatment strategies in humans.

That’s the case in this technicolor snapshot showing early patterns of inflammation in the brain of a relatively young mouse bred to develop a condition similar to AD. You can see abnormally high levels of inflammation throughout the front part of the brain (orange, green) as well as in its middle part—the septum that divides the brain’s two sides. This level of inflammation suggests that the brain has been injured.

What’s striking is that no inflammation is detectable in parts of the brain rich in cholinergic neurons (pink), a distinct type of nerve cell that helps to control memory, movement, and attention. Though these neurons still remain healthy, researchers would like to know if the inflammation also will destroy them as AD progresses.

This colorful image comes from medical student Sakar Budhathoki, who earlier worked in the NIH labs of Lorna Role and David Talmage, National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS). Budhathoki, teaming with postdoctoral scientist Mala Ananth, used a specially designed wide-field scanner that sweeps across brain tissue to light up fluorescent markers and capture the image. It’s one of the scanning approaches pioneered in the Role and Talmage labs [1,2].

The two NIH labs are exploring possible links between abnormal inflammation and damage to the brain’s cholinergic signaling system. In fact, medications that target cholinergic function remain the first line of treatment for people with AD and other dementias. And yet, researchers still haven’t adequately determined when, why, and how the loss of these cholinergic neurons relates to AD.

It’s a rich area of basic research that offers hope for greater understanding of AD in the future. It’s also the source of some fascinating images like this one, which was part of the 2022 Show Us Your BRAIN! Photo and Video Contest, supported by NIH’s Brain Research Through Advancing Innovative Neurotechnologies® (BRAIN) Initiative.

References:

[1] NeuRegenerate: A framework for visualizing neurodegeneration. Boorboor S, Mathew S, Ananth M, Talmage D, Role LW, Kaufman AE. IEEE Trans Vis Comput Graph. 2021;Nov 10;PP.

[2] NeuroConstruct: 3D reconstruction and visualization of neurites in optical microscopy brain images. Ghahremani P, Boorboor S, Mirhosseini P, Gudisagar C, Ananth M, Talmage D, Role LW, Kaufman AE. IEEE Trans Vis Comput Graph. 2022 Dec;28(12):4951-4965.

Links:

Alzheimer’s Disease & Related Dementias (National Institute on Aging/NIH)

Role Lab (National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke/NIH)

Talmage Lab (NINDS)

The Brain Research Through Advancing Innovative Neurotechnologies® (BRAIN) Initiative (NIH)

Show Us Your BRAINs! Photo and Video Contest (BRAIN Initiative)

NIH Support: National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke

The Amazing Brain: Seeing Two Memories at Once

Posted on by Lawrence Tabak, D.D.S., Ph.D.

The NIH’s Brain Research Through Advancing Innovative Neurotechnologies® (BRAIN) Initiative is revolutionizing our understanding of the human brain. As described in the initiative’s name, the development of innovative imaging technologies will enable researchers to see the brain in new and increasingly dynamic ways. Each year, the initiative celebrates some standout and especially creative examples of such advances in the “Show Us Your BRAINs! Photo & Video Contest. During most of August, I’ll share some of the most eye-catching developments in our blog series, The Amazing Brain.

In this fascinating image, you’re seeing two stored memories, which scientists call engrams, in the hippocampus region of a mouse’s brain. The engrams show the neural intersection of a good memory (green) and a bad memory (pink). You can also see the nuclei of many neurons (blue), including nearby neurons not involved in the memory formation.

This award-winning image was produced by Stephanie Grella in the lab of NIH-supported neuroscientist Steve Ramirez, Boston University, MA. It’s also not the first time that the blog has featured Grella’s technical artistry. Grella, who will soon launch her own lab at Loyola University, Chicago, previously captured what a single memory looks like.

To capture two memories at once, Grella relied on a technology known as optogenetics. This powerful method allows researchers to genetically engineer neurons and selectively activate them in laboratory mice using blue light. In this case, Grella used a harmless virus to label neurons involved in recording a positive experience with a light-sensitive molecule, known as an opsin. Another molecular label was used to make those same cells appear green when activated.

After any new memory is formed, there’s a period of up to about 24 hours during which the memory is malleable. Then, the memory tends to stabilize. But with each retrieval, the memory can be modified as it restabilizes, a process known as memory reconsolidation.

Grella and team decided to try to use memory reconsolidation to their advantage to neutralize an existing fear. To do this, they placed their mice in an environment that had previously startled them. When a mouse was retrieving a fearful memory (pink), the researchers activated with light associated with the positive memory (green), which for these particular mice consisted of positive interactions with other mice. The aim was to override or disrupt the fearful memory.

As shown by the green all throughout the image, the experiment worked. While the mice still showed some traces of the fearful memory (pink), Grella explained that the specific cells that were the focus of her study shifted to the positive memory (green).

What’s perhaps even more telling is that the evidence suggests the mice didn’t just trade one memory for another. Rather, it appears that activating a positive memory actually suppressed or neutralized the animal’s fearful memory. The hope is that this approach might one day inspire methods to help people overcome negative and unwanted memories, such as those that play a role in post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and other mental health issues.

Links:

Stephanie Grella (Boston University, MA)

Ramirez Group (Boston University)

Brain Research through Advancing Innovative Neurotechnologies® (BRAIN) Initiative (NIH)

Show Us Your BRAINs Photo & Video Contest (BRAIN Initiative)

NIH Support: BRAIN Initiative; Common Fund

Human Brain Compresses Working Memories into Low-Res ‘Summaries’

Posted on by Lawrence Tabak, D.D.S., Ph.D.

You have probably done it already a few times today. Paused to remember a password, a shopping list, a phone number, or maybe the score to last night’s ballgame. The ability to store and recall needed information, called working memory, is essential for most of the human brain’s higher cognitive processes.

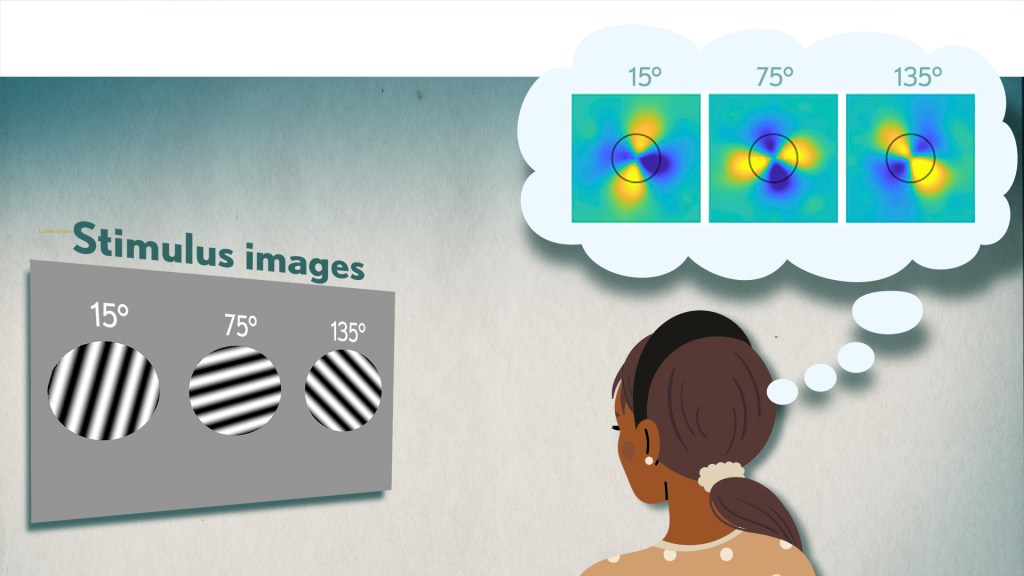

Researchers are still just beginning to piece together how working memory functions. But recently, NIH-funded researchers added an intriguing new piece to this neurobiological puzzle: how visual working memories are “formatted” and stored in the brain.

The findings, published in the journal Neuron, show that the visual cortex—the brain’s primary region for receiving, integrating, and processing visual information from the eye’s retina—acts more like a blackboard than a camera. That is, the visual cortex doesn’t photograph all the complex details of a visual image, such as the color of paper on which your password is written or the precise series of lines that make up the letters. Instead, it recodes visual information into something more like simple chalkboard sketches.

The discovery suggests that those pared down, low-res representations serve as a kind of abstract summary, capturing the relevant information while discarding features that aren’t relevant to the task at hand. It also shows that different visual inputs, such as spatial orientation and motion, may be stored in virtually identical, shared memory formats.

The new study, from Clayton Curtis and Yuna Kwak, New York University, New York, builds upon a known fundamental aspect of working memory. Many years ago, it was determined that the human brain tends to recode visual information. For instance, if passed a 10-digit phone number on a card, the visual information gets recoded and stored in the brain as the sounds of the numbers being read aloud.

Curtis and Kwak wanted to learn more about how the brain formats representations of working memory in patterns of brain activity. To find out, they measured brain activity with functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) while participants used their visual working memory.

In each test, study participants were asked to remember a visual stimulus presented to them for 12 seconds and then make a memory-based judgment on what they’d just seen. In some trials, as shown in the image above, participants were shown a tilted grating, a series of black and white lines oriented at a particular angle. In others, they observed a cloud of dots, all moving in a direction to represent those same angles. After a short break, participants were asked to recall and precisely indicate the angle of the grating’s tilt or the dot cloud’s motion as accurately as possible.

It turned out that either visual stimulus—the grating or moving dots—resulted in the same patterns of neural activity in the visual cortex and parietal cortex. The parietal cortex is a part of the brain used in memory processing and storage.

These two distinct visual memories carrying the same relevant information seemed to have been recoded into a shared abstract memory format. As a result, the pattern of brain activity trained to recall motion direction was indistinguishable from that trained to recall the grating orientation.

This result indicated that only the task-relevant features of the visual stimuli had been extracted and recoded into a shared memory format. But Curtis and Kwak wondered whether there might be more to this finding.

To take a closer look, they used a sophisticated model that allowed them to project the three-dimensional patterns of brain activity into a more-informative, two-dimensional representation of visual space. And, indeed, their analysis of the data revealed a line-like pattern, similar to a chalkboard sketch that’s oriented at the relevant angles.

The findings suggest that participants weren’t actually remembering the grating or a complex cloud of moving dots at all. Instead, they’d compressed the images into a line representing the angle that they’d been asked to remember.

Many questions remain about how remembering a simple angle, a relatively straightforward memory formation, will translate to the more-complex sets of information stored in our working memory. On a technical level, though, the findings show that working memory can now be accessed and captured in ways that hadn’t been possible before. This will help to delineate the commonalities in working memory formation and the possible differences, whether it’s remembering a password, a shopping list, or the score of your team’s big victory last night.

Reference:

[1] Unveiling the abstract format of mnemonic representations. Kwak Y, Curtis CE. Neuron. 2022, April 7; 110(1-7).

Links:

Working Memory (National Institute of Mental Health/NIH)

The Curtis Lab (New York University, New York)

NIH Support: National Eye Institute

The Synchronicity of Memory

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

You may think that you’re looking at a telescopic heat-map of a distant planet, with clickable thumbnail images to the right featuring its unique topography. In fact, what you’re looking at is a small region of the brain that’s measured in micrometers and stands out as a fascinating frontier of discovery into the very origins of thought and cognition.

It’s a section of a mouse hippocampus, a multi-tasking region of the brain that’s central to memory formation. What makes the image on the left so interesting is it shows four individual neurons (numbered circles) helping to form a memory.

The table of images on the right shows in greater detail how the memory is formed. You see those same four neurons, their activity logged individually. Cooler colors—indigo to turquoise—indicate background or low neuronal activity; warmer colors—yellow to red—indicate high neuronal activity.

Now, take a closer look at the rows of the table that are labeled “Initial.” The four neurons have responded to an initial two-part training session: the sounding of a tone (gray-shaded columns) followed by a stimulus (red-shaded columns) less than a minute later. The neurons, while active (multi-colored pattern), don’t fire in unison or at the same activity levels. A memory has not yet been formed.

That’s not the case just below in the rows labeled “Trained.” After several rounds of reinforcing the one-two sequence, neurons fire together at comparable activity levels in response to the tone (gray) followed by the now-predictable stimulus (red). This process of firing in unison, called neuronal synchronization, encodes the memory. In fact, the four neurons even deactivate in unison after each prompt (unshaded columns).

These fascinating images are the first to show an association between neuronal burst synchronization and hippocampus-dependent memory formation. This discovery has broad implications, from improving memory to reconditioning the mental associations that underlie post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

This research comes from a team led by the NIH-supported investigator Xuanmao Chen, University of New Hampshire, Durham. In the study, published in the FASEB Journal, Chen and colleagues used deep-brain imaging technology to shed new light on some old-fashioned classical conditioning: Pavlovian training [1].

Over a century ago, Ivan Pavlov conducted experiments that conditioned dogs to salivate at the sound of a bell that signaled their feeding time. This concept of “classical conditioning” is central to our understanding of how we humans form certain types of memories. A baby smiles at the sound of her mother’s voice. Stores play holiday music at the end of the year, hoping the positive childhood association puts shoppers in the mood to buy more gifts. Our phone plays a distinctive tone, and we immediately check our text messages. In each example, the association with an otherwise neutral stimulus is learned—and stored in the brain as a “declarative,” or explicit, memory.

The researchers wanted to see what happened in neural cells when mice learned a new association. They applied Pavlov’s learning paradigm, training mice over repeated sessions by pairing an audible tone and, about 30 seconds later, a brief, mild foot stimulus. Mice instinctively halt their activities, or freeze, in response to the foot stimulus. After a few tone-stimulus training sessions, the mice also began freezing after the tone was sounded. They had formed a conditioned response.

During these training sessions, Chen and his colleagues were able to take high-resolution, real-time images of the hippocampus. This allowed them to track the same four neurons over the course of the day—and watch as memory creation, in the form of neuronal synchronization, took place. Later, during recall experiments, the tone itself elicited both the behavioral change and the coordinated neuronal response—if with a bit less regularity. It’s something we humans experience whenever we forget a computer password!

The researchers went on to capture even more evidence. They showed that these neurons, which became part of the stored “engram,” or physical location of the memory, were already active even before they were synchronized. This finding contributes to recent work challenging the long-held paradigm that memory-eligible neurons “switch on” from a silent state to form a memory [2]. The researchers offered a new name for these active neurons: “primed,” as opposed to “silent.”

Chen and his colleagues continue studying the priming process and working out more of the underlying molecular details. They’re attempting to determine how the process is regulated and primed neurons become synchronized. And, of course, the big question: how does this translate into an actual memory in other living creatures? The next round of results should be memorable!

References:

[1] Induction of activity synchronization among primed hippocampal neurons out of random dynamics is key for trace memory formation and retrieval. Zhou Y, Qiu L, Wang H, Chen X. FASEB J. 2020 Mar;34(3):3658–3676.

[2] Memory engrams: Recalling the past and imagining the future. Josselyn S, Tonegawa S. Science 2020 Jan 3;367(6473):eaaw4325.

Links:

Brain Basics: Know Your Brain (National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke/NIH)

Neuroanatomy, Hippocampus Fogwe LA, Reddy V, Mesfin FB. StatPearls Publishing (National Library of Medicine/NIH)

Xuanmao Chen (University of New Hampshire, Durham)

NIH Support: National Institute of Mental Health; National Institute on Aging; National Institute of General Medical Sciences

The People’s Picks for Best Posts

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

It’s 2021—Happy New Year! Time sure flies in the blogosphere. It seems like just yesterday that I started the NIH Director’s Blog to highlight recent advances in biology and medicine, many supported by NIH. Yet it turns out that more than eight years have passed since this blog got rolling and we are fast approaching my 1,000th post!

I’m pleased that millions of you have clicked on these posts to check out some very cool science and learn more about NIH and its mission. Thanks to the wonders of social media software, we’ve been able to tally up those views to determine each year’s most-popular post. So, I thought it would be fun to ring in the New Year by looking back at a few of your favorites, sort of a geeky version of a top 10 countdown or the People’s Choice Awards. It was interesting to see what topics generated the greatest interest. Spoiler alert: diet and exercise seemed to matter a lot! So, without further ado, I present the winners:

2013: Fighting Obesity: New Hopes from Brown Fat. Brown fat, one of several types of fat made by our bodies, was long thought to produce body heat rather than store energy. But Shingo Kajimura and his team at the University of California, San Francisco, showed in a study published in the journal Nature, that brown fat does more than that. They discovered a gene that acts as a molecular switch to produce brown fat, then linked mutations in this gene to obesity in humans.

What was also nice about this blog post is that it appeared just after Kajimura had started his own lab. In fact, this was one of the lab’s first publications. One of my goals when starting the blog was to feature young researchers, and this work certainly deserved the attention it got from blog readers. Since highlighting this work, research on brown fat has continued to progress, with new evidence in humans suggesting that brown fat is an effective target to improve glucose homeostasis.

2014: In Memory of Sam Berns. I wrote this blog post as a tribute to someone who will always be very near and dear to me. Sam Berns was born with Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome, one of the rarest of rare diseases. After receiving the sad news that this brave young man had passed away, I wrote: “Sam may have only lived 17 years, but in his short life he taught the rest of us a lot about how to live.”

Affecting approximately 400 people worldwide, progeria causes premature aging. Without treatment, children with progeria, who have completely normal intellectual development, die of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, on average in their early teens.

From interactions with Sam and his parents in the early 2000s, I started to study progeria in my NIH lab, eventually identifying the gene responsible for the disorder. My group and others have learned a lot since then. So, it was heartening last November when the Food and Drug Administration approved the first treatment for progeria. It’s an oral medication called Zokinvy (lonafarnib) that helps prevent the buildup of defective protein that has deadly consequences. In clinical trials, the drug increased the average survival time of those with progeria by more than two years. It’s a good beginning, but we have much more work to do in the memory of Sam and to help others with progeria. Watch for more about new developments in applying gene editing to progeria in the next few days.

2015: Cytotoxic T Cells on Patrol. Readers absolutely loved this post. When the American Society of Cell Biology held its first annual video competition, called CellDance, my blog featured some of the winners. Among them was this captivating video from Alex Ritter, then working with cell biologist Jennifer Lippincott-Schwartz of NIH’s Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. The video stars a roving, specialized component of our immune system called cytotoxic T cells. Their job is to seek out and destroy any foreign or detrimental cells. Here, these T cells literally convince a problem cell to commit suicide, a process that takes about 10 minutes from detection to death.

These cytotoxic T cells are critical players in cancer immunotherapy, in which a patient’s own immune system is enlisted to control and, in some cases, even cure the cancer. Cancer immunotherapy remains a promising area of research that continues to progress, with a lot of attention now being focused on developing immunotherapies for common, solid tumors like breast cancer. Ritter is currently completing a postdoctoral fellowship in the laboratory of Ira Mellman, Genentech, South San Francisco. His focus has shifted to how cancer cells protect themselves from T cells. And video buffs—get this—Ritter says he’s now created even cooler videos that than the one in this post.

2016: Exercise Releases Brain-Healthy Protein. The research literature is pretty clear: exercise is good for the brain. In this very popular post, researchers led by Hyo Youl Moon and Henriette van Praag of NIH’s National Institute on Aging identified a protein secreted by skeletal muscle cells to help explore the muscle-brain connection. In a study in Cell Metabolism, Moon and his team showed that this protein called cathepsin B makes its way into the brain and after a good workout influences the development of new neural connections. This post is also memorable to me for the photo collage that accompanied the original post. Why? If you look closely at the bottom right, you’ll see me exercising—part of my regular morning routine!

2017: Muscle Enzyme Explains Weight Gain in Middle Age. The struggle to maintain a healthy weight is a lifelong challenge for many of us. While several risk factors for weight gain, such as counting calories, are within our control, there’s a major one that isn’t: age. Jay Chung, a researcher with NIH’s National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, and his team discovered that the normal aging process causes levels of an enzyme called DNA-PK to rise in animals as they approach middle age. While the enzyme is known for its role in DNA repair, their studies showed it also slows down metabolism, making it more difficult to burn fat.

Since publishing this paper in Cell Metabolism, Chung has been busy trying to understand how aging increases the activity of DNA-PK and its ability to suppress renewal of the cell’s energy-producing mitochondria. Without renewal of damaged mitochondria, excess oxidants accumulate in cells that then activate DNA-PK, which contributed to the damage in the first place. Chung calls it a “vicious cycle” of aging and one that we’ll be learning more about in the future.

2018: Has an Alternative to Table Sugar Contributed to the C. Diff. Epidemic? This impressive bit of microbial detective work had blog readers clicking and commenting for several weeks. So, it’s no surprise that it was the runaway People’s Choice of 2018.

Clostridium difficile (C. diff) is a common bacterium that lives harmlessly in the gut of most people. But taking antibiotics can upset the normal balance of healthy gut microbes, allowing C. diff. to multiply and produce toxins that cause inflammation and diarrhea.

In the 2000s, C. diff. infections became far more serious and common in American hospitals, and Robert Britton, a researcher at Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, wanted to know why. He and his team discovered that two subtypes of C. diff have adapted to feed on the sugar trehalose, which was approved as a food additive in the United States during the early 2000s. The team’s findings, published in the journal Nature, suggested that hospitals and nursing homes battling C. diff. outbreaks may want to take a closer look at the effect of trehalose in the diet of their patients.

2019: Study Finds No Benefit for Dietary Supplements. This post that was another one that sparked a firestorm of comments from readers. A team of NIH-supported researchers, led by Fang Fang Zhang, Tufts University, Boston, found that people who reported taking dietary supplements had about the same risk of dying as those who got their nutrients through food. What’s more, the mortality benefits associated with adequate intake of vitamin A, vitamin K, magnesium, zinc, and copper were limited to amounts that are available from food consumption. The researchers based their conclusion on an analysis of the well-known National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) between 1999-2000 and 2009-2010 survey data. The team, which reported its data in the Annals of Internal Medicine, also uncovered some evidence suggesting that certain supplements might even be harmful to health when taken in excess.

2020: Genes, Blood Type Tied to Risk of Severe COVID-19. Typically, my blog focuses on research involving many different diseases. That changed in 2020 due to the emergence of a formidable public health challenge: the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. Since last March, the blog has featured 85 posts on COVID-19, covering all aspects of the research response and attracting more visitors than ever. And which post got the most views? It was one that highlighted a study, published last June in the New England Journal of Medicine, that suggested the clues to people’s variable responses to COVID-19 may be found in our genes and our blood types.

The researchers found that gene variants in two regions of the human genome are associated with severe COVID-19 and correspondingly carry a greater risk of COVID-19-related death. The two stretches of DNA implicated as harboring risks for severe COVID-19 are known to carry some intriguing genes, including one that determines blood type and others that play various roles in the immune system.

In fact, the findings suggest that people with blood type A face a 50 percent greater risk of needing oxygen support or a ventilator should they become infected with the novel coronavirus. In contrast, people with blood type O appear to have about a 50 percent reduced risk of severe COVID-19.

That’s it for the blog’s year-by-year Top Hits. But wait! I’d also like to give shout outs to the People’s Choice winners in two other important categories—history and cool science images.

Top History Post: HeLa Cells: A New Chapter in An Enduring Story. Published in August 2013, this post remains one of the blog’s greatest hits with readers. The post highlights science’s use of cancer cells taken in the 1950s from a young Black woman named Henrietta Lacks. These “HeLa” cells had an amazing property not seen before: they could be grown continuously in laboratory conditions. The “new chapter” featured in this post is an agreement with the Lacks family that gives researchers access to the HeLa genome data, while still protecting the family’s privacy and recognizing their enormous contribution to medical research. And the acknowledgments rightfully keep coming from those who know this remarkable story, which has been chronicled in both book and film. Recently, the U.S. Senate and House of Representatives passed the Henrietta Lacks Enhancing Cancer Research Act to honor her extraordinary life and examine access to government-funded cancer clinical trials for traditionally underrepresented groups.

Top Snapshots of Life: A Close-up of COVID-19 in Lung Cells. My blog posts come in several categories. One that you may have noticed is “Snapshots of Life,” which provides a showcase for cool images that appear in scientific journals and often dominate Science as Art contests. My blog has published dozens of these eye-catching images, representing a broad spectrum of the biomedical sciences. But the blog People’s Choice goes to a very recent addition that reveals exactly what happens to cells in the human airway when they are infected with the coronavirus responsible for COVID-19. This vivid image, published in the New England Journal of Medicine, comes from the lab of pediatric pulmonologist Camille Ehre, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. This image squeezed in just ahead of another highly popular post from Steve Ramirez, Boston University, in 2019 that showed “What a Memory Looks Like.”

As we look ahead to 2021, I want to thank each of my blog’s readers for your views and comments over the last eight years. I love to hear from you, so keep on clicking! I’m confident that 2021 will generate a lot more amazing and bloggable science, including even more progress toward ending the COVID-19 pandemic that made our past year so very challenging.

How Our Brains Replay Memories

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Note to my blog readers: the whole world is now facing a major threat from the COVID-19 pandemic. We at NIH are doing everything we can to apply the best and most powerful science to the development of diagnostics, therapeutics, and vaccines, while also implementing public health measures to protect our staff and the patients in our hospital. This crisis is expected to span many weeks, and I will occasionally report on COVID-19 in this blog format. Meanwhile, science continues to progress on many other fronts—and so I will continue to try to bring you stories across a wide range of topics. Perhaps everyone can use a little break now and then from the coronavirus news? Today’s blog takes you into the intricacies of memory.

When recalling the name of an acquaintance, you might replay an earlier introduction, trying to remember the correct combination of first and last names. (Was it Scott James? Or James Scott?) Now, neuroscientists have found that in the split second before you come up with the right answer, your brain’s neurons fire in the same order as when you first learned the information [1].

This new insight into memory retrieval comes from recording the electrical activity of thousands of neurons in the brains of six people during memory tests of random word pairs, such as “jeep” and “crow.” While similar firing patterns had been described before in mice, the new study is the first to confirm that the human brain stores memories in specific sequences of neural activity that can be replayed again and again.

The new study, published in the journal Science, is the latest insight from neurosurgeon and researcher Kareem Zaghloul at NIH’s National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS). Zaghloul’s team has for years been involved in an NIH Clinical Center study for patients with drug-resistant epilepsy whose seizures cannot be controlled with drugs.

As part of this work, his surgical team often temporarily places a 4 millimeter-by-4 millimeter array of tiny electrodes on the surface of the brains of the study’s participants. They do this in an effort to pinpoint brain tissues that may be the source of their seizures before performing surgery to remove them. With a patient’s informed consent to take part in additional research, the procedure also has led to a series of insights into what happens in the human brain when we make and later retrieve new memories.

Here’s how it works: The researchers record electrical currents as participants are asked to learn random word pairs presented to them on a computer screen, such as “cake” and “fox,” or “lime” and “camel.” After a period of rest, their brain activity is again recorded as they are given a word and asked to recall the matching word.

Last year, the researchers reported that the split second before a person got the right answer, tiny ripples of electrical activity appeared in two specific areas of the brain [2]. The team also had shown that, when a person correctly recalled a word pair, the brain showed patterns of activity that corresponded to those formed when he or she first learned to make a word association.

The new work takes this a step further. As study participants learned a word pair, the researchers noticed not only the initial rippling wave of electricity, but also that particular neurons in the brain’s cerebral cortex fired repeatedly in a sequential order. In fact, with each new word pair, the researchers observed unique firing patterns among the active neurons.

If the order of neuronal firing was essential for storing new memories, the researchers reasoned that the same would be true for correctly retrieving the information. And, indeed, that’s what they were able to show. For example, when individuals were shown “cake” for a second time, they replayed a very similar firing pattern to the one recorded initially for this word just milliseconds before correctly recalling the paired word “fox.”

The researchers then calculated the average sequence similarity between the firing patterns of learning and retrieval. They found that as a person recalled a word, those patterns gradually became more similar. Just before a correct answer was given, the recorded neurons locked onto the right firing sequence. That didn’t happen when a person gave an incorrect answer.

Further analysis confirmed that the exact order of neural firing was specific to each word pair. The findings show that our memories are encoded as unique sequences that must be replayed for accurate retrieval, though we still don’t understand the molecular mechanisms that undergird this.

Zaghloul reports that there’s still more to learn about how these processes are influenced by other factors such as our attention. It’s not yet known whether the brain replays sequences similarly when retrieving longer-term memories. Along with these intriguing insights into normal learning and memory, the researchers think this line of research will yield important clues as to what changes in people who suffer from memory disorders, with potentially important implications for developing the next generation of treatments.

Reference:

[1] Replay of cortical spiking sequences during human memory retrieval. Vaz AP, Wittig JH Jr, Inati SK, Zaghloul KA. Science. 2020 Mar 6;367(6482):1131-1134.

[2] Coupled ripple oscillations between the medial temporal lobe and neocortex retrieve human memory. Vaz AP, Inati SK, Brunel N, Zaghloul KA. Science. 2019 Mar 1;363(6430):975-978.

Links:

Epilepsy Information Page (National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke/NIH)

Brain Basics (NINDS)

Zaghloul Lab (NINDS)

NIH Support: National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke; National Institute of General Medical Sciences

Discovering the Brain’s Nightly “Rinse Cycle”

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Getting plenty of deep, restful sleep is essential for our physical and mental health. Now comes word of yet another way that sleep is good for us: it triggers rhythmic waves of blood and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) that appear to function much like a washing machine’s rinse cycle, which may help to clear the brain of toxic waste on a regular basis.

The video above uses functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to take you inside a person’s brain to see this newly discovered rinse cycle in action. First, you see a wave of blood flow (red, yellow) that’s closely tied to an underlying slow-wave of electrical activity (not visible). As the blood recedes, CSF (blue) increases and then drops back again. Then, the cycle—lasting about 20 seconds—starts over again.

The findings, published recently in the journal Science, are the first to suggest that the brain’s well-known ebb and flow of blood and electrical activity during sleep may also trigger cleansing waves of blood and CSF. While the experiments were conducted in healthy adults, further study of this phenomenon may help explain why poor sleep or loss of sleep has previously been associated with the spread of toxic proteins and worsening memory loss in people with Alzheimer’s disease.

In the new study, Laura Lewis, Boston University, MA, and her colleagues at the Martinos Center for Biomedical Imaging, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston. recorded the electrical activity and took fMRI images of the brains of 13 young, healthy adults as they slept. The NIH-funded team also built a computer model to learn more about the fluid dynamics of what goes on in the brain during sleep. And, as it turns out, their sophisticated model predicted exactly what they observed in the brains of living humans: slow waves of electrical activity followed by alternating waves of blood and CSF.

Lewis says her team is now working to come up with even better ways to capture CSF flow in the brain during sleep. Currently, people who volunteer for such experiments have to be able to fall asleep while wearing an electroencephalogram (EEG) cap inside of a noisy MRI machine—no easy feat. The researchers are also recruiting older adults to begin exploring how age-related changes in brain activity during sleep may affect the associated fluid dynamics.

Reference:

[1] Coupled electrophysiological, hemodynamic, and cerebrospinal fluid oscillations in human sleep. Fultz NE, Bonmassar G, Setsompop K, Stickgold RA, Rosen BR, Polimeni JR, Lewis LD. Science. 2019 Nov 1;366(6465):628-631.

Links:

Sleep and Memory (National Institute of Mental Health/NIH)

Sleep Deprivation and Deficiency (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute/NIH)

Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Dementias (National Institute on Aging/NIH)

NIH Support: National Institute of Mental Health; National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering; National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke

A Real-Time Look at Value-Based Decision Making

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

All of us make many decisions every day. For most things, such as which jacket to wear or where to grab a cup of coffee, there’s usually no right answer, so we often decide using values rooted in our past experiences. Now, neuroscientists have identified the part of the mammalian brain that stores information essential to such value-based decision making.

Researchers zeroed in on this particular brain region, known as the retrosplenial cortex (RSC), by analyzing movies—including the clip shown about 32 seconds into this video—that captured in real time what goes on in the brains of mice as they make decisions. Each white circle is a neuron, and the flickers of light reflect their activity: the brighter the light, the more active the neuron at that point in time.

All told, the NIH-funded team, led by Ryoma Hattori and Takaki Komiyama, University of California at San Diego, La Jolla, made recordings of more than 45,000 neurons across six regions of the mouse brain [1]. Neural activity isn’t usually visible. But, in this case, researchers used mice that had been genetically engineered so that their neurons, when activated, expressed a protein that glowed.

Their system was also set up to encourage the mice to make value-based decisions, including choosing between two drinking tubes, each with a different probability of delivering water. During this decision-making process, the RSC proved to be the region of the brain where neurons persistently lit up, reflecting how the mouse evaluated one option over the other.

The new discovery, described in the journal Cell, comes as something of a surprise to neuroscientists because the RSC hadn’t previously been implicated in value-based decisions. To gather additional evidence, the researchers turned to optogenetics, a technique that enabled them to use light to inactivate neurons in the RSC’s of living animals. These studies confirmed that, with the RSC turned off, the mice couldn’t retrieve value information based on past experience.

The researchers note that the RSC is heavily interconnected with other key brain regions, including those involved in learning, memory, and controlling movement. This indicates that the RSC may be well situated to serve as a hub for storing value information, allowing it to be accessed and acted upon when it is needed.

The findings are yet another amazing example of how advances coming out of the NIH-led Brain Research through Advancing Innovative Neurotechnologies® (BRAIN) Initiative are revolutionizing our understanding of the brain. In the future, the team hopes to learn more about how the RSC stores this information and sends it to other parts of the brain. They note that it will also be important to explore how activity in this brain area may be altered in schizophrenia, dementia, substance abuse, and other conditions that may affect decision-making abilities. It will also be interesting to see how this develops during childhood and adolescence.

Reference:

[1] Area-Specificity and Plasticity of History-Dependent Value Coding During Learning. Hattori R, Danskin B, Babic Z, Mlynaryk N, Komiyama T. Cell. 2019 Jun 13;177(7):1858-1872.e15.

Links:

Brain Research through Advancing Innovative Neurotechnologies® (BRAIN) Initiative (NIH)

Komiyama Lab (UCSD, La Jolla)

NIH Support: National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke; National Eye Institute; National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders

What a Memory Looks Like

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Your brain has the capacity to store a lifetime of memories, covering everything from the name of your first pet to your latest computer password. But what does a memory actually look like? Thanks to some very cool neuroscience, you are looking at one.

The physical manifestation of a memory, or engram, consists of clusters of brain cells active when a specific memory was formed. Your brain’s hippocampus plays an important role in storing and retrieving these memories. In this cross-section of a mouse hippocampus, imaged by the lab of NIH-supported neuroscientist Steve Ramirez, at Boston University, cells belonging to an engram are green, while blue indicates those not involved in forming the memory.

When a memory is recalled, the cells within an engram reactivate and turn on, to varying degrees, other neural circuits (e.g., sight, sound, smell, emotions) that were active when that memory was recorded. It’s not clear how these brain-wide connections are made. But it appears that engrams are the gatekeepers that mediate memory.

The story of this research dates back several years, when Ramirez helped develop a system that made it possible to image engrams by tagging cells in the mouse brain with fluorescent dyes. Using an innovative technology developed by other researchers, called optogenetics, Ramirez’s team then discovered it could shine light onto a collection of hippocampal neurons storing a specific memory and reactivate the sensation associated with the memory [1].

Ramirez has since gone on to show that, at least in mice, optogenetics can be used to trick the brain into creating a false memory [2]. From this work, he has also come to the interesting and somewhat troubling conclusion that the most accurate memories appear to be the ones that are never recalled. The reason: the mammalian brain edits—and slightly changes—memories whenever they are accessed.

All of the above suggested to Ramirez that, given its tremendous plasticity, the brain may possess the power to downplay a traumatic memory or to boost a pleasant recollection. Toward that end, Ramirez’s team is now using its mouse system to explore ways of suppressing one engram while enhancing another [3].

For Ramirez, though, the ultimate goal is to develop brain-wide maps that chart all of the neural networks involved in recording, storing, and retrieving memories. He recently was awarded an NIH Director’s Transformative Research Award to begin the process. Such maps will be invaluable in determining how stress affects memory, as well as what goes wrong in dementia and other devastating memory disorders.

References:

[1] Optogenetic stimulation of a hippocampal engram activates fear memory recall. Liu X, Ramirez S, Pang PT, Puryear CB, Govindarajan A, Deisseroth K, Tonegawa S. Nature. 2012 Mar 22;484(7394):381-385.

[2] Creating a false memory in the hippocampus. Ramirez S, Liu X, Lin PA, Suh J, Pignatelli M, Redondo RL, Ryan TJ, Tonegawa S. Science. 2013 Jul 26;341(6144):387-391.

[3] Artificially Enhancing and Suppressing Hippocampus-Mediated Memories. Chen BK, Murawski NJ, Cincotta C, McKissick O, Finkelstein A, Hamidi AB, Merfeld E, Doucette E, Grella SL, Shpokayte M, Zaki Y, Fortin A, Ramirez S. Curr Biol. 2019 Jun 3;29(11):1885-1894.

Links:

The Ramirez Group (Boston University, MA)

Ramirez Project Information (Common Fund/NIH)

NIH Director’s Early Independence Award (Common Fund)

NIH Director’s Transformative Research Award (Common Fund)

NIH Support: Common Fund

New Grants Explore Benefits of Music on Health

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

It’s not every day you get to perform with one of the finest voices on the planet. What an honor it was to join renowned opera singer Renée Fleming back in May for a rendition of “How Can I Keep from Singing?” at the NIH’s J. Edward Rall Cultural Lecture. Yet our duet was so much more. Between the song’s timeless message and Renée’s matchless soprano, the music filled me with a profound sense of joy, like being briefly lifted outside myself into a place of beauty and well-being. How does that happen?

Indeed, the benefits of music for human health and well-being have long been recognized. But biomedical science still has a quite limited understanding of music’s mechanisms of action in the brain, as well as its potential to ease symptoms of an array of disorders including Parkinson’s disease, stroke, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). In a major step toward using rigorous science to realize music’s potential for improving human health, NIH has just awarded $20 million over five years to support the first research projects of the Sound Health initiative. Launched a couple of years ago, Sound Health is a partnership between NIH and the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts, in association with the National Endowment for the Arts.

With support from 10 NIH institutes and centers, the Sound Health awardees will, among other things, study how music might improve the motor skills of people with Parkinson’s disease. Previous research has shown that the beat of a metronome can steady the gait of someone with Parkinson’s disease, but more research is needed to determine exactly why that happens.

Other fascinating areas to be explored by the Sound Health awardees include:

• Assessing how active music interventions, often called music therapies, affect multiple biomarkers that correlate with improvement in health status. The aim is to provide a more holistic understanding of how such interventions serve to ease cancer-related stress and possibly even improve immune function.

• Investigating the effects of music on the developing brain of infants as they learn to talk. Such work may be especially helpful for youngsters at high risk for speech and language disorders.

• Studying synchronization of musical rhythm as part of social development. This research will look at how this process is disrupted in children with autism spectrum disorder, possibly suggesting ways of developing music-based interventions to improve communication.

• Examining the memory-related impacts of repeated exposures to a certain song or musical phrase, including those “earworms” that get “stuck” in our heads. This work might tell us more about how music sometimes serves as a cue for retrieving associated memories, even in people whose memory skills are impaired by Alzheimer’s disease or other cognitive disorders.

• Tracing the developmental timeline—from childhood to adulthood—of how music shapes the brain. This will include studying how musical training at different points on that timeline may influence attention span, executive function, social/emotional functioning, and language skills.

We are fortunate to live in an exceptional time of discovery in neuroscience, as well as an extraordinary era of creativity in music. These Sound Health grants represent just the beginning of what I hope will be a long and productive partnership that brings these creative fields together. I am convinced that the power of science holds tremendous promise for improving the effectiveness of music-based interventions, and expanding their reach to improve the health and well-being of people suffering from a wide variety of conditions.

Links:

The Soprano and the Scientist: A Conversation About Music and Medicine, (National Public Radio, June 2, 2017)

NIH Workshop on Music and Health, January 2017

Sound Health (NIH)

NIH Support: National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health; National Eye Institute; National Institute on Aging; National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders; National Institute of Mental Health; National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke; National Institute of Nursing Research; Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences Research; Office of the Director

Next Page