neurodegenerative disorders

Understanding Causes of Devastating Neurodegenerative Condition Affecting Children

Posted on by Lawrence Tabak, D.D.S., Ph.D.

A common theme among parents and family members caring for a child with the rare Batten disease is “love, hope, cure.” While inspiring levels of love and hope are found among these amazing families, a cure has been more elusive. One reason is rooted in the need for more basic research. Although researchers have identified an altered gene underlying Batten disease, they’ve had difficulty pinpointing where and how the gene’s abnormal protein product malfunctions, especially in cells within the nervous system.

Now, this investment in more basic research has paid off. In a paper just published in the journal Nature Communications, an international research team pinpointed where and how a key cellular process breaks down in the nervous system to cause Batten disease, sometimes referred to as CLN3 disease [1]. While there’s still a long way to go in learning exactly how to overcome the cellular malfunction, the findings mark an important step forward toward developing targeted treatments for Batten disease and progress in the quest for a cure.

The research also offers yet another excellent example of how studying rare diseases helps to advance our fundamental understanding of human biology. It shows that helping those touched by Batten disease can shed a brighter light on basic cellular processes that drive other diseases, rare and common.

Batten disease affects about 14,000 people worldwide [2]. For those with the juvenile form of this inherited disease of the nervous system, parents may first notice their seemingly healthy child has difficulty saying words, sudden problems with vision or movement, and changes in behavior. Tragically for parents, with no approved treatments to reverse these symptoms, the disease will worsen, leading to severe vision loss, frequent seizures, and impaired motor skills. The disease can be fatal as early as late childhood or the teenage years.

Batten disease also goes by the more technical name of juvenile neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis. Using this technical name, it represents one of the more than 70 medically recognized lysosomal storage disorders.

These disorders share a breakdown in the ability of membrane-bound cellular components, known as lysosomes, to degrade the molecular waste products of normal cell biology. As a result, all this undegraded material builds up and eventually kills affected cells. In people with Batten disease, the lost and damaged cells cause progressive dysfunction within the nervous system.

Researchers have known for a while that the most common cause of this breakdown in people with Batten disease is the inheritance of two defective copies of a gene called CLN3. As mentioned above, what’s been missing is a more detailed understanding of what exactly a working copy of the CLN3 gene does and how its loss leads to the changes seen in those with this condition.

Hoping to solve this puzzle was an NIH-supported basic research team led by Alessia Calcagni and Andrea Ballabio, Baylor College of Medicine and Texas Children’s Hospital, Houston, and Telethon Institute of Genetics and Medicine, Naples, Italy.

As described in their latest paper, the researchers first generated an antibody that allowed them to visualize where in cells the protein encoded by CLN3 is found. Their studies unexpectedly showed that this protein has a role outside, not inside, the cell’s estimated 50-to-1,000 lysosomes. Before reaching the lysosomes, the protein first moves through another cellular component called the Golgi body, where many proteins are packaged.

They then identified all the other proteins that interact with the CLN3 protein in the Golgi body and elsewhere in the cell. Their data showed that CLN3 interacts with proteins known for transporting other proteins within the cell and forming new lysosomes.

That gave them a valuable clue: the CLN3 gene must be a player in these fundamentally important cellular processes of protein transport and lysosome formation. Among the proteins CLN3 interacts with in the Golgi body is a particular receptor called M6PR. The receptor known for its role in recognizing lysosomal enzymes and delivering them to the lysosomes, where they go to work inside these bubble-like structures degrading cellular waste products.

The researchers found that loss of CLN3 led this important M6PR receptor to be broken down within lysosomes. The breakdown, in turn, altered the normal shape of new lysosomes, and that limits their functionality. The researchers also showed that restoring CLN3 in cells that lacked this gene also restored the production of more functional lysosomes and lysosomal enzymes.

Overall, the findings point to a major role for CLN3 in the formation of lysosomes and their ability to function. Importantly, the findings also offer clues for understanding the mechanisms that underlie other forms of lysosomal storage disease, which collectively affect as many as one in every 40,000 people [3]. The work also may have broader implications for common neurodegenerative diseases, such as Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s disease.

Most of all, this paper demonstrates the power of basic research to define needed molecular targets. It shows how these fundamental studies are helping families affected by Batten disease and supporting their love, hope, and quest for a cure.

References:

[1] Loss of the batten disease protein CLN3 leads to mis-trafficking of M6PR and defective autophagic-lysosomal reformation. Calcagni’ A, Staiano L, Zampelli N, Minopoli N, Herz NJ, Cullen PJ, Parenti G, De Matteis MA, Grumati P, Ballabio A, et al. Nat Commun. 2023 Jul 3;14(1):3911. doi: 10.1038/s41467-023-39643-7. PMID: 37400440; PMCID: PMC10317969.

[2] Batten Disease. Boston Children’s Hospital.

[3] Lysosomal storage diseases. Cleveland Clinic fact sheet, June 27, 2022.

Links:

Batten Disease (National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke/NIH)

Rare Diseases (NIH)

Alessia Calcagni (Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX)

Andrea Ballabio (Telethon Institute of Genetics and Medicine, Naples, Italy)

NIH Support: National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke; National Cancer Institute; National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences

An Inflammatory View of Early Alzheimer’s Disease

Posted on by Lawrence Tabak, D.D.S., Ph.D.

Detecting the earliest signs of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) in middle-aged people and tracking its progression over time in research studies continue to be challenging. But it is easier to do in shorter-lived mammalian models of AD, especially when paired with cutting-edge imaging tools that look across different regions of the brain. These tools can help basic researchers detect telltale early changes that might point the way to better prevention or treatment strategies in humans.

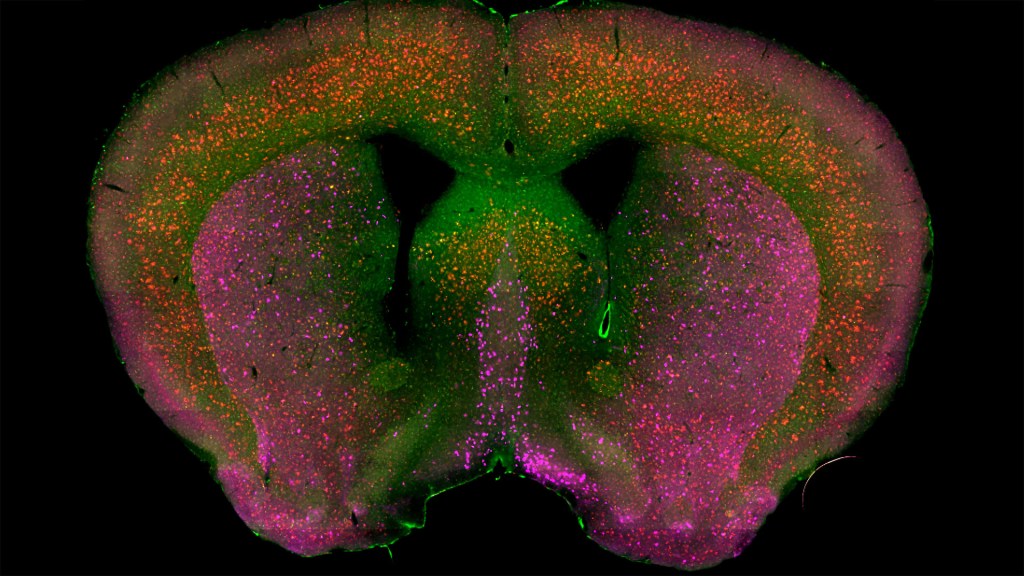

That’s the case in this technicolor snapshot showing early patterns of inflammation in the brain of a relatively young mouse bred to develop a condition similar to AD. You can see abnormally high levels of inflammation throughout the front part of the brain (orange, green) as well as in its middle part—the septum that divides the brain’s two sides. This level of inflammation suggests that the brain has been injured.

What’s striking is that no inflammation is detectable in parts of the brain rich in cholinergic neurons (pink), a distinct type of nerve cell that helps to control memory, movement, and attention. Though these neurons still remain healthy, researchers would like to know if the inflammation also will destroy them as AD progresses.

This colorful image comes from medical student Sakar Budhathoki, who earlier worked in the NIH labs of Lorna Role and David Talmage, National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS). Budhathoki, teaming with postdoctoral scientist Mala Ananth, used a specially designed wide-field scanner that sweeps across brain tissue to light up fluorescent markers and capture the image. It’s one of the scanning approaches pioneered in the Role and Talmage labs [1,2].

The two NIH labs are exploring possible links between abnormal inflammation and damage to the brain’s cholinergic signaling system. In fact, medications that target cholinergic function remain the first line of treatment for people with AD and other dementias. And yet, researchers still haven’t adequately determined when, why, and how the loss of these cholinergic neurons relates to AD.

It’s a rich area of basic research that offers hope for greater understanding of AD in the future. It’s also the source of some fascinating images like this one, which was part of the 2022 Show Us Your BRAIN! Photo and Video Contest, supported by NIH’s Brain Research Through Advancing Innovative Neurotechnologies® (BRAIN) Initiative.

References:

[1] NeuRegenerate: A framework for visualizing neurodegeneration. Boorboor S, Mathew S, Ananth M, Talmage D, Role LW, Kaufman AE. IEEE Trans Vis Comput Graph. 2021;Nov 10;PP.

[2] NeuroConstruct: 3D reconstruction and visualization of neurites in optical microscopy brain images. Ghahremani P, Boorboor S, Mirhosseini P, Gudisagar C, Ananth M, Talmage D, Role LW, Kaufman AE. IEEE Trans Vis Comput Graph. 2022 Dec;28(12):4951-4965.

Links:

Alzheimer’s Disease & Related Dementias (National Institute on Aging/NIH)

Role Lab (National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke/NIH)

Talmage Lab (NINDS)

The Brain Research Through Advancing Innovative Neurotechnologies® (BRAIN) Initiative (NIH)

Show Us Your BRAINs! Photo and Video Contest (BRAIN Initiative)

NIH Support: National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke

Understanding Neuronal Diversity in the Spinal Cord

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

The spinal cord, as a key part of our body’s central nervous system, contains millions of neurons that actively convey sensory and motor (movement) information to and from the brain. Scientists have long sorted these spinal neurons into what they call “cardinal” classes, a classification system based primarily on the developmental origin of each nerve cell. Now, by taking advantage of the power of single-cell genetic analysis, they’re finding that spinal neurons are more diverse than once thought.

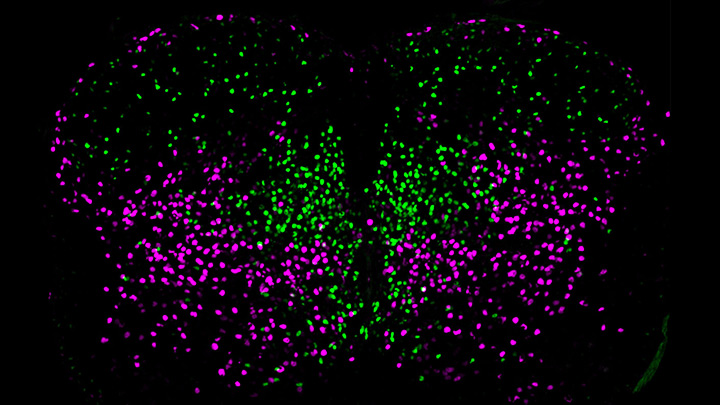

This image helps to visualize the story. Each dot represents the nucleus of a spinal neuron in a mouse; humans have a very similar arrangement. Most of these neurons are involved in the regulation of motor control, but they also differ in important ways. Some are involved in local connections (green), such as those that signal outward to a limb and prompt us to pull away reflexively when we touch painful stimuli, such as a hot frying pan. Others are involved in long-range connections (magenta), relaying commands across spinal segments and even upward to the brain. These enable us, for example, to swing our arms while running to help maintain balance.

It turns out that these two types of spinal neurons also have distinctive genetic signatures. That’s why researchers could label them here in different colors and tell them apart. Being able to distinguish more precisely among spinal neurons will prove useful in identifying precisely which ones are affected by a spinal cord injury or neurodegenerative disease, key information in learning to engineer new tissue to heal the damage.

This image comes from a study, published recently in the journal Science, conducted by an NIH-supported team led by Samuel Pfaff, Salk Institute for Biological Studies, La Jolla, CA. Pfaff and his colleagues, including Peter Osseward and Marito Hayashi, realized that the various classes and subtypes of neurons in our spines arose over the course of evolutionary time. They reasoned that the most-primitive original neurons would have gradually evolved subtypes with more specialized and diverse capabilities. They thought they could infer this evolutionary history by looking for conserved and then distinct, specialized gene-expression signatures in the different neural subtypes.

The researchers turned to single-cell RNA sequencing technologies to look for important similarities and differences in the genes expressed in nearly 7,000 mouse spinal neurons. They then used this vast collection of genomic data to group the neurons into closely related clusters, in much the same way that scientists might group related organisms into an evolutionary family tree based on careful study of their DNA.

The first major gene expression pattern they saw divided the spinal neurons into two types: sensory-related and motor-related. This suggested to them that one of the first steps in spinal cord evolution may have been a division of labor of spinal neurons into those two fundamentally important roles.

Further analyses divided the sensory-related neurons into excitatory neurons, which make neurons more likely to fire; and inhibitory neurons, which dampen neural firing. Then, the researchers zoomed in on motor-related neurons and found something unexpected. They discovered the cells fell into two distinct molecular groups based on whether they had long-range or short-range connections in the body. Researches were even more surprised when further study showed that those distinct connectivity signatures were shared across cardinal classes.

All of this means that, while previously scientists had to use many different genetic tags to narrow in on a particular type of neuron, they can now do it with just two: a previously known tag for cardinal class and the newly discovered genetic tag for long-range vs. short-range connections.

Not only is this newfound ability a great boon to basic neuroscientists, it also could prove useful for translational and clinical researchers trying to determine which specific neurons are affected by a spinal injury or disease. Eventually, it may even point the way to strategies for regrowing just the right set of neurons to repair serious neurologic problems. It’s a vivid reminder that fundamental discoveries, such as this one, often can lead to unexpected and important breakthroughs with potential to make a real difference in people’s lives.

Reference:

[1] Conserved genetic signatures parcellate cardinal spinal neuron classes into local and projection subsets. Osseward PJ 2nd, Amin ND, Moore JD, Temple BA, Barriga BK, Bachmann LC, Beltran F Jr, Gullo M, Clark RC, Driscoll SP, Pfaff SL, Hayashi M. Science. 2021 Apr 23;372(6540):385-393.

Links:

What Are the Parts of the Nervous System? (Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development/NIH)

Spinal Cord Injury (National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke/NIH)

Samuel Pfaff (Salk Institute, La Jolla, CA)

NIH Support: National Institute of Mental Health; National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke; Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development

New Study Points to Targetable Protective Factor in Alzheimer’s Disease

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

If you’ve spent time with individuals affected with Alzheimer’s disease (AD), you might have noticed that some people lose their memory and other cognitive skills more slowly than others. Why is that? New findings indicate that at least part of the answer may lie in differences in their immune responses.

Researchers have now found that slower loss of cognitive skills in people with AD correlates with higher levels of a protein that helps immune cells clear plaque-like cellular debris from the brain [1]. The efficiency of this clean-up process in the brain can be measured via fragments of the protein that shed into the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). This suggests that the protein, called TREM2, and the immune system as a whole, may be promising targets to help fight Alzheimer’s disease.

The findings come from an international research team led by Michael Ewers, Institute for Stroke and Dementia Research, Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München, Germany, and Christian Haass, Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München, Germany and German Center for Neurodegenerative Diseases. The researchers got interested in TREM2 following the discovery several years ago that people carrying rare genetic variants for the protein were two to three times more likely to develop AD late in life.

Not much was previously known about TREM2, so this finding from a genome wide association study (GWAS) was a surprise. In the brain, it turns out that TREM2 proteins are primarily made by microglia. These scavenging immune cells help to keep the brain healthy, acting as a clean-up crew that clears cellular debris, including the plaque-like amyloid-beta that is a hallmark of AD.

In subsequent studies, Haass and colleagues showed in mouse models of AD that TREM2 helps to shift microglia into high gear for clearing amyloid plaques [2]. This animal work and that of others helped to strengthen the case that TREM2 may play an important role in AD. But what did these data mean for people with this devastating condition?

There had been some hints of a connection between TREM2 and the progression of AD in humans. In the study published in Science Translational Medicine, the researchers took a deeper look by taking advantage of the NIH-funded Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI).

ADNI began more than a decade ago to develop methods for early AD detection, intervention, and treatment. The initiative makes all its data freely available to AD researchers all around the world. That allowed Ewers, Haass, and colleagues to focus their attention on 385 older ADNI participants, both with and without AD, who had been followed for an average of four years.

Their primary hypothesis was that individuals with AD and evidence of higher TREM2 levels at the outset of the study would show over the years less change in their cognitive abilities and in the volume of their hippocampus, a portion of the brain important for learning and memory. And, indeed, that’s exactly what they found.

In individuals with comparable AD, whether mild cognitive impairment or dementia, those having higher levels of a TREM2 fragment in their CSF showed a slower decline in memory. Those with evidence of a higher ratio of TREM2 relative to the tau protein in their CSF also progressed more slowly from normal cognition to early signs of AD or from mild cognitive impairment to full-blown dementia.

While it’s important to note that correlation isn’t causation, the findings suggest that treatments designed to boost TREM2 and the activation of microglia in the brain might hold promise for slowing the progression of AD in people. The challenge will be to determine when and how to target TREM2, and a great deal of research is now underway to make these discoveries.

Since its launch more than a decade ago, ADNI has made many important contributions to AD research. This new study is yet another fine example that should come as encouraging news to people with AD and their families.

References:

[1] Increased soluble TREM2 in cerebrospinal fluid is associated with reduced cognitive and clinical decline in Alzheimer’s disease. Ewers M, Franzmeier N, Suárez-Calvet M, Morenas-Rodriguez E, Caballero MAA, Kleinberger G, Piccio L, Cruchaga C, Deming Y, Dichgans M, Trojanowski JQ, Shaw LM, Weiner MW, Haass C; Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative. Sci Transl Med. 2019 Aug 28;11(507).

[2] Loss of TREM2 function increases amyloid seeding but reduces plaque-associated ApoE. Parhizkar S, Arzberger T, Brendel M, Kleinberger G, Deussing M, Focke C, Nuscher B, Xiong M, Ghasemigharagoz A, Katzmarski N, Krasemann S, Lichtenthaler SF, Müller SA, Colombo A, Monasor LS, Tahirovic S, Herms J, Willem M, Pettkus N, Butovsky O, Bartenstein P, Edbauer D, Rominger A, Ertürk A, Grathwohl SA, Neher JJ, Holtzman DM, Meyer-Luehmann M, Haass C. Nat Neurosci. 2019 Feb;22(2):191-204.

Links:

Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Dementias (National Institute on Aging/NIH)

Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (University of Southern California, Los Angeles)

Ewers Lab (University Hospital Munich, Germany)

Haass Lab (Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München, Germany)

German Center for Neurodegenerative Diseases (Bonn)

Institute for Stroke and Dementia Research (Munich, Germany)

NIH Support: National Institute on Aging

Gut-Dwelling Bacterium Consumes Parkinson’s Drug

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Scientists continue to uncover the many fascinating ways in which the trillions of microbes that inhabit the human body influence our health. Now comes yet another surprising discovery: a medicine-eating bacterium residing in the human gut that may affect how well someone responds to the most commonly prescribed drug for Parkinson’s disease.

There have been previous hints that gut microbes might influence the effectiveness of levodopa (L-dopa), which helps to ease the stiffness, rigidity, and slowness of movement associated with Parkinson’s disease. Now, in findings published in Science, an NIH-funded team has identified a specific, gut-dwelling bacterium that consumes L-dopa [1]. The scientists have also identified the bacterial genes and enzymes involved in the process.

Parkinson’s disease is a progressive neurodegenerative condition in which the dopamine-producing cells in a portion of the brain called the substantia nigra begin to sicken and die. Because these cells and their dopamine are critical for controlling movement, their death leads to the familiar tremor, difficulty moving, and the characteristic slow gait. As the disease progresses, cognitive and behavioral problems can take hold, including depression, personality shifts, and sleep disturbances.

For the 10 million people in the world now living with this neurodegenerative disorder, and for those who’ve gone before them, L-dopa has been for the last 50 years the mainstay of treatment to help alleviate those motor symptoms. The drug is a precursor of dopamine, and, unlike dopamine, it has the advantage of crossing the blood-brain barrier. Once inside the brain, an enzyme called DOPA decarboxylase converts L-dopa to dopamine.

Unfortunately, only a small fraction of L-dopa ever reaches the brain, contributing to big differences in the drug’s efficacy from person to person. Since the 1970s, researchers have suspected that these differences could be traced, in part, to microbes in the gut breaking down L-dopa before it gets to the brain.

To take a closer look in the new study, Vayu Maini Rekdal and Emily Balskus, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, turned to data from the NIH-supported Human Microbiome Project (HMP). The project used DNA sequencing to identify and characterize the diverse collection of microbes that populate the healthy human body.

The researchers sifted through the HMP database for bacterial DNA sequences that appeared to encode an enzyme capable of converting L-dopa to dopamine. They found what they were looking for in a bacterial group known as Enterococcus, which often inhabits the human gastrointestinal tract.

Next, they tested the ability of seven representative Enterococcus strains to transform L-dopa. Only one fit the bill: a bacterium called Enterococcus faecalis, which commonly resides in a healthy gut microbiome. In their tests, this bacterium avidly consumed all the L-dopa, using its own version of a decarboxylase enzyme. When a specific gene in its genome was inactivated, E. faecalis stopped breaking down L-dopa.

These studies also revealed variability among human microbiome samples. In seven stool samples, the microbes tested didn’t consume L-dopa at all. But in 12 other samples, microbes consumed 25 to 98 percent of the L-dopa!

The researchers went on to find a strong association between the degree of L-dopa consumption and the abundance of E. faecalis in a particular microbiome sample. They also showed that adding E. faecalis to a sample that couldn’t consume L-dopa transformed it into one that could.

So how can this information be used to help people with Parkinson’s disease? Answers are already appearing. The researchers have found a small molecule that prevents the E. faecalis decarboxylase from modifying L-dopa—without harming the microbe and possibly destabilizing an otherwise healthy gut microbiome.

The finding suggests that the human gut microbiome might hold a key to predicting how well people with Parkinson’s disease will respond to L-dopa, and ultimately improving treatment outcomes. The finding also serves to remind us just how much the microbiome still has to tell us about human health and well-being.

Reference:

[1] Discovery and inhibition of an interspecies gut bacterial pathway for Levodopa metabolism. Maini Rekdal V, Bess EN, Bisanz JE, Turnbaugh PJ, Balskus EP. Science. 2019 Jun 14;364(6445).

Links:

Parkinson’s Disease Information Page (National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke/NIH)

Balskus Lab (Harvard University, Cambridge, MA)

NIH Support: National Institute of General Medical Sciences; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute

Mood-Altering Messenger Goes Nuclear

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Serotonin is best known for its role as a chemical messenger in the brain, helping to regulate mood, appetite, sleep, and many other functions. It exerts these influences by binding to its receptor on the surface of neural cells. But startling new work suggests the impact of serotonin does not end there: the molecule also can enter a cell’s nucleus and directly switch on genes.

While much more study is needed, this is a potentially groundbreaking discovery. Not only could it have implications for managing depression and other mood disorders, it may also open new avenues for treating substance abuse and neurodegenerative diseases.

To understand how serotonin contributes to switching genes on and off, a lesson on epigenetics is helpful. Keep in mind that the DNA instruction book of all cells is essentially the same, yet the chapters of the book are read in very different ways by cells in different parts of the body. Epigenetics refers to chemical marks on DNA itself or on the protein “spools” called histones that package DNA. These marks influence the activity of genes in a particular cell without changing the underlying DNA sequence, switching them on and off or acting as “volume knobs” to turn the activity of particular genes up or down.

The marks include various chemical groups—including acetyl, phosphate, or methyl—which are added at precise locations to those spool-like proteins called histones. The addition of such groups alters the accessibility of the DNA for copying into messenger RNA and producing needed proteins.

In the study reported in Nature, researchers led by Ian Maze and postdoctoral researcher Lorna Farrelly, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, followed a hunch that serotonin molecules might also get added to histones [1]. There had been hints that it might be possible. For instance, earlier evidence suggested that inside cells, serotonin could enter the nucleus. There also was evidence that serotonin could attach to proteins outside the nucleus in a process called serotonylation.

These data begged the question: Is serotonylation important in the brain and/or other living tissues that produce serotonin in vivo? After a lot of hard work, the answer now appears to be yes.

These NIH-supported researchers found that serotonylation does indeed occur in the cell nucleus. They also identified a particular enzyme that directly attaches serotonin molecules to histone proteins. With serotonin attached, DNA loosens on its spool, allowing for increased gene expression.

The team found that histone serotonylation takes place in serotonin-producing human neurons derived from induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs). They also observed this process occurring in the brains of developing mice.

In fact, the researchers found evidence of those serotonin marks in many parts of the body. They are especially prevalent in the brain and gut, where serotonin also is produced in significant amounts. Those marks consistently correlate with areas of active gene expression.

The serotonin mark often occurs on histones in combination with a second methyl mark. The researchers suggest that this double marking of histones might help to further reinforce an active state of gene expression.

This work demonstrates that serotonin can directly influence gene expression in a manner that’s wholly separate from its previously known role in transmitting chemical messages from one neuron to the next. And, there are likely other surprises in store.

The newly discovered role of serotonin in modifying gene expression may contribute significantly to our understanding of mood disorders and other psychiatric conditions with known links to serotonin signals, suggesting potentially new targets for therapeutic intervention. But for now, this fundamental discovery raises many more intriguing questions than it answers.

Science is full of surprises, and this paper is definitely one of them. Will this kind of histone marking occur with other chemical messengers, such as dopamine and acetylcholine? This unexpected discovery now allows us to track serotonin and perhaps some of the brain’s other chemical messengers to see what they might be doing in the cell nucleus and whether this information might one day help in treating the millions of Americans with mood and behavioral disorders.

Reference:

[1] Histone serotonylation is a permissive modification that enhances TFIID binding to H3K4me3. Farrelly LA, Thompson RE, Zhao S, Lepack AE, Lyu Y, Bhanu NV, Zhang B, Loh YE, Ramakrishnan A, Vadodaria KC, Heard KJ, Erikson G, Nakadai T, Bastle RM, Lukasak BJ, Zebroski H 3rd, Alenina N, Bader M, Berton O, Roeder RG, Molina H, Gage FH, Shen L, Garcia BA, Li H, Muir TW, Maze I. Nature. 2019 Mar 13. [Epub ahead of print]

Links:

Any Mood Disorder (National Institute of Mental Health/NIH)

Drugs, Brains, and Behavior: The Science of Addiction (National Institute on Drug Abuse/NIH)

Epigenomics (National Human Genome Research Institute/NIH)

Maze Lab (Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, NY)

NIH Support: National Institute on Drug Abuse; National Institute of Mental Health; National Institute of General Medical Sciences; National Cancer Institute

Creative Minds: Reprogramming the Brain

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

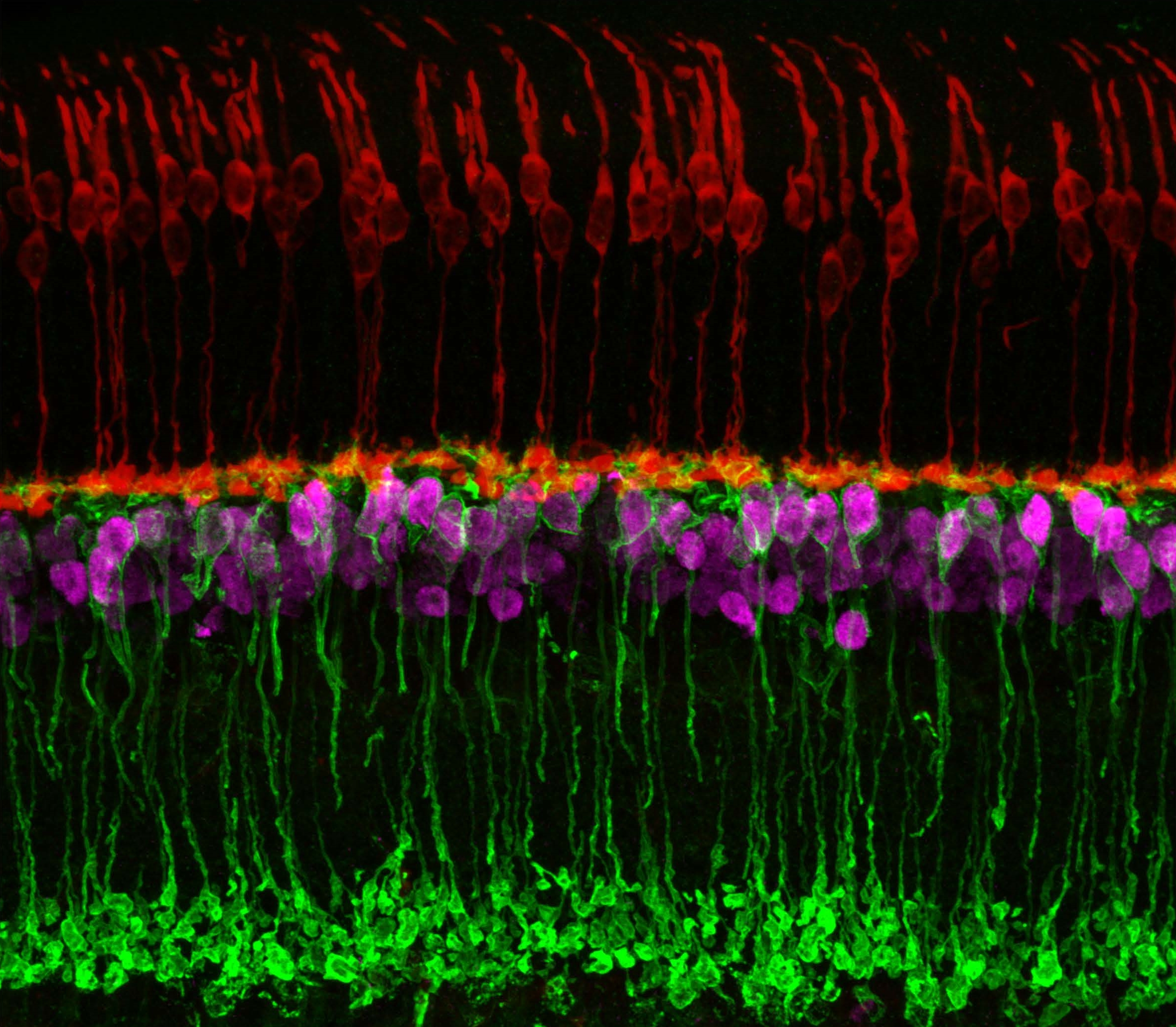

Caption: Neuronal circuits in the mouse retina. Cone photoreceptors (red) enable color vision; bipolar neurons (magenta) relay information further along the circuit; and a subtype of bipolar neuron (green) helps process signals sensed by other photoreceptors in dim light.

Credit: Brian Liu and Melanie Samuel, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston.

When most people think of reprogramming something, they probably think of writing code for a computer or typing commands into their smartphone. Melanie Samuel thinks of brain circuits, the networks of interconnected neurons that allow different parts of the brain to work together in processing information.

Samuel, a researcher at Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, wants to learn to reprogram the connections, or synapses, of brain circuits that function less well in aging and disease and limit our memory and ability to learn. She has received a 2016 NIH Director’s New Innovator Award to decipher the molecular cues that encourage the repair of damaged synapses or enable neurons to form new connections with other neurons. Because extensive synapse loss is central to most degenerative brain diseases, Samuel’s reprogramming efforts could help point the way to preventing or correcting wiring defects before they advance to serious and potentially irreversible cognitive problems.

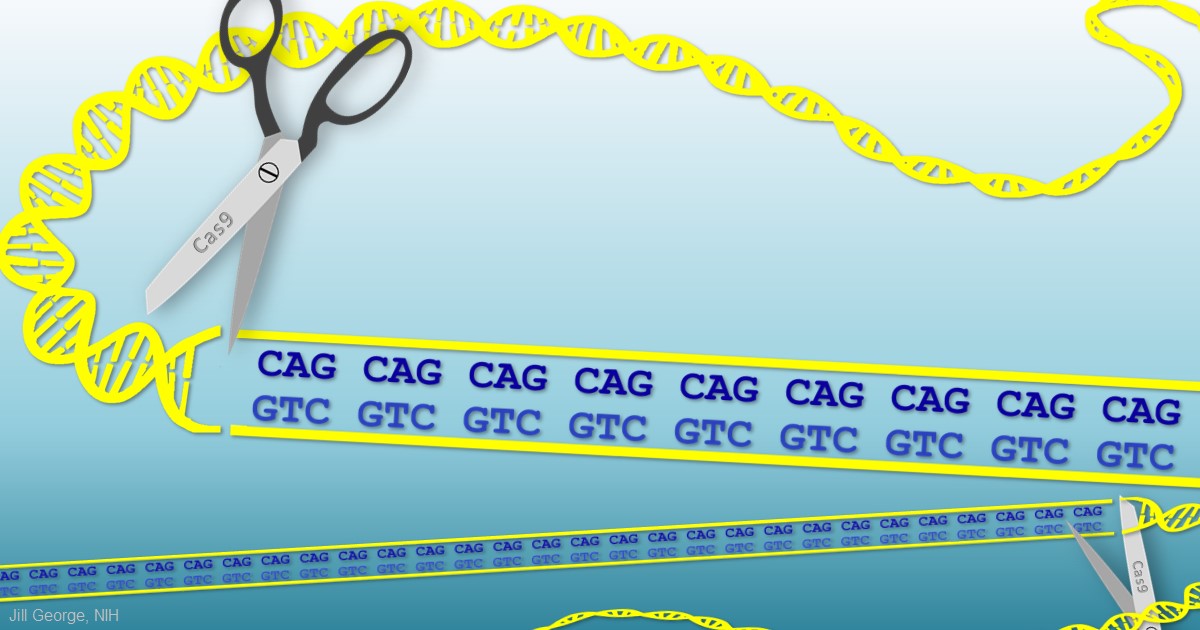

Huntington’s Disease: Gene Editing Shows Promise in Mouse Studies

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

My father was a folk song collector, and I grew up listening to the music of Woody Guthrie. On July 14th, folk music enthusiasts will be celebrating the 105th anniversary of Guthrie’s birth in his hometown of Okemah, OK. Besides being renowned for writing “This Land is Your Land” and other folk classics, Guthrie has another more tragic claim to fame: he provided the world with a glimpse at the devastation caused by a rare, inherited neurological disorder called Huntington’s disease.

My father was a folk song collector, and I grew up listening to the music of Woody Guthrie. On July 14th, folk music enthusiasts will be celebrating the 105th anniversary of Guthrie’s birth in his hometown of Okemah, OK. Besides being renowned for writing “This Land is Your Land” and other folk classics, Guthrie has another more tragic claim to fame: he provided the world with a glimpse at the devastation caused by a rare, inherited neurological disorder called Huntington’s disease.

When Guthrie died from complications of Huntington’s a half-century ago, the disease was untreatable. Sadly, it still is. But years of basic science advances, combined with the promise of innovative gene editing systems such as CRISPR/Cas9, are providing renewed hope that we will someday be able to treat or even cure Huntington’s disease, along with many other inherited disorders.

Next Page

For centuries, people have yearned for an elixir capable of restoring youth to their aging bodies and minds. It sounds like pure fantasy, but, in recent years, researchers have shown that the blood of young mice can exert a regenerative effect

For centuries, people have yearned for an elixir capable of restoring youth to their aging bodies and minds. It sounds like pure fantasy, but, in recent years, researchers have shown that the blood of young mice can exert a regenerative effect