Accelerating Medicines Partnership

A Rare Public Health Challenge

Posted on by Joni Rutter, Ph.D., National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences

Most public health challenges may seem obvious. The COVID-19 pandemic, for example, swept the globe and in some way touched the lives of everyone. But not all public health challenges are as readily apparent.

Rare diseases are a case in point. While individually each disease is rare, collectively rare diseases are common: More than 10,000 rare diseases affect nearly 400 million people worldwide. In the United States, the prevalence of rare diseases (over 30 million people) rivals or exceeds that of common diseases such as diabetes (37.3 million people), Alzheimer’s disease (6.5 million people), and heart failure (6.2 million people).

Shouldering the Burden of Rare Diseases

As with common diseases, the personal and economic burdens of rare diseases are immense. People who live with rare diseases often struggle for years before they receive an accurate diagnosis, with some remaining undiagnosed for a decade or longer. The diagnostic odyssey includes countless doctor visits, unnecessary tests and procedures, and wrong diagnoses. For people in rural and low-income communities, lack of access to care is an additional barrier to an accurate diagnosis. And a diagnosis often doesn’t lead to better health—only about 5 percent of rare diseases have U.S. Food and Drug Administration–approved treatments.

Collectively, the personal burdens of those with rare diseases impose a significant economic cost on the nation. When quantifying the health care expenses for people with rare diseases, we found that they have three to five times greater costs than those without rare diseases [1]. In the United States, the total direct medical costs for those with rare diseases is approximately $400 billion annually, a figure validated independently by the EveryLife Foundation for Rare Diseases. The EveryLife study also included indirect and non-medical costs, resulting in a higher total economic burden of nearly $1 trillion annually [2].

What’s even starker is that the true scope and impact of rare diseases actually may be greater because rare diseases aren’t easily visible in our health care system. Many of the diseases are too rare to have a code that identifies them in the electronic health record (EHR).

Speeding Up the Search for Solutions

Each and every day, NIH’s National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) works with patients, advocates, clinicians, and researchers to meet the public health challenge of rare diseases. Driving those conversations are three overarching goals to help people living with rare diseases get the high-quality care they need, faster:

1. Shorten the duration of the diagnostic odyssey by more than half. The diagnostic odyssey for someone with a rare disease takes on average seven years, and there are several ways we can speed the journey. For example, we are designing computational tools to detect rare genetic disorders from EHR data. This work is part of a broader research effort focused on using genetic analysis and machine learning to make it easier for health care providers to diagnose people with rare diseases correctly. Also, connecting patients more quickly with each other and the research community can hasten the search for answers. Check out the resources below to learn about rare diseases, find patient support organizations, and get involved in research efforts.

2. Develop treatments for more than one rare disease at a time. A key strategy is leveraging what rare diseases have in common. Some of our efforts build upon the fact that 80–85 percent of rare diseases are genetic. We can use this knowledge to develop genetic and molecular interventions for groups of rare diseases. Two programs—the Platform Vector Gene Therapy pilot project and the Bespoke Gene Therapy Consortium, which is part of the public-private Accelerating Medicines Partnership®—are streamlining the gene therapy development process. Their ultimate goal is to make gene therapies more accessible to many people with rare diseases. We also have joined in to advance the clinical application of genome editing for rare genetic diseases.

The NCATS-led Rare Diseases Clinical Research Network, which is supported across NIH, brings scientists together with rare disease organizations and patient advocacy groups to better understand common characteristics, which also might speed clinical research. With this in mind, we are adapting a clinical trial strategy used in cancer research to test a single therapy on multiple rare diseases.

3. Make it easier and more efficient for scientists to discover and develop treatments for rare diseases. NCATS develops ways for new treatments to reach people more quickly. Repurposing drugs, for example, is revealing already-approved drugs that may work for rare diseases. Programs such as Therapeutics for Rare and Neglected Diseases and Bridging Interventional Development Gaps move basic research discoveries in the lab closer to becoming new drugs. Ambitious initiatives, such as the Biomedical Data Translator, unite data from biomedical research, clinical trials, and EHRs to find treatments for rare diseases faster.

The COVID-19 pandemic showed us the power of working together to solve public health challenges. Let’s now come together to address the public health challenge of rare diseases. If you want to get involved, please join us at Rare Disease Day at NIH 2023 on February 28. You’ll hear personal stories, learn about the latest research, and discover helpful resources. I hope to see you there!

References:

[1] The IDeaS initiative: pilot study to assess the impact of rare diseases on patients and healthcare systems. Tisdale A, Cutillo CM, Nathan R, Russo P, Laraway B, Haendel M, Nowak D, Hasche C, Chan CH, Griese E, Dawkins H, Shukla O, Pearce DA, Rutter JL, Pariser AR. Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases. 2021 Oct 22; ;16(1):429.

[2] The national economic burden of rare disease in the United States in 2019. Yang G, Cintina I, Pariser A, Oehrlein E, Sullivan J, Kennedy A. Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases. 2022 Apr 12;17(1):163.

Links:

Rare Disease Day at NIH 2023 (National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences/NIH)

Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center (NCATS)

Toolkit for Patient-Focused Therapy Development (NCATS)

Rare Diseases Registry Program (NCATS)

Rare Diseases Research and Resources (NCATS)

Note: Dr. Lawrence Tabak, who performs the duties of the NIH Director, has asked the heads of NIH’s Institutes and Centers (ICs) to contribute occasional guest posts to the blog to highlight some of the interesting science that they support and conduct. This is the 23rd in the series of NIH IC guest posts that will run until a new permanent NIH director is in place.

Share this:

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Telegram (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window)

- Click to print (Opens in new window)

Posted In: Generic

Tags: Accelerating Medicines Partnership, AMP, Bespoke Gene Therapy Consortium, Biomedical Data Translator, Bridging Interventional Development Gaps, drug repurposing, EHR, electronic health records, EveryLife Foundation for Rare Diseases, gene therapy, genetic diseases, genome editing, NCATS, Platform Vector Gene Therapy, Rare Disease Day, Rare Disease Day at NIH 2023, rare diseases, Rare Diseases Clinical Research Network, Therapeutics for Rare and Neglected Diseases

Partnership to Expand Effective Gene Therapies for Rare Diseases

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Rare diseases aren’t so rare. Collectively, up to 30 million Americans, many of them children, are born with one of the approximately 7,000 known rare diseases. Most of these millions of people also share a common genetic feature: their diseases are caused by an alteration in a single gene.

Many of these alterations could theoretically be targeted with therapies designed to correct or replace the faulty gene. But there have been significant obstacles in realizing this dream. The science of gene therapy has been making real progress, but pursuing promising approaches all the way to clinical trials and gaining approval from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) is still very difficult. Another challenge is economic: for the rarest of these conditions (which is most of them), the market is so small that most companies have no financial incentive to pursue them.

To overcome these obstacles and provide hope for those with rare diseases, we need a new way of doing things. One way to do things differently—and more efficiently—is the recently launched Bespoke Gene Therapy Consortium (BGTC). It is a bold partnership of NIH, the FDA, 10 pharmaceutical companies, several non-profit organizations, and the Foundation for the National Institutes of Health [1]. Its aim: optimize the gene therapy development process and help fill the significant unmet medical needs of people with rare diseases.

The BGTC, which is also part of NIH’s Accelerating Medicines Partnership® (AMP®), will enable the easier, faster, and cheaper pursuit of “bespoke” gene therapies, meaning made for a particular customer or user. The goal of the Consortium is to reduce the cost of gene therapy protocols and increase the likelihood of success, making it more attractive for companies to invest in rare diseases and bring treatments to patients who desperately need them.

Fortunately, there is already some precedent. The BGTC effort builds on a pilot project led by NIH’s National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) known as Platform Vector Gene Therapy (PaVe-GT). This pilot project has helped to develop adeno-associated viruses (AAVs), which are small benign viruses engineered in the lab to carry a therapeutic gene. They are commonly used in gene therapy-related clinical trials of rare diseases.

Since the launch of PaVe-GT two years ago, the project has helped to introduce greater efficiency to gene therapy trials for rare disease. It’s also offered a way to get around the standard one-disease-at-a-time approach to therapeutic development that has stymied progress in treating rare conditions.

The BGTC will now continue to advance in-depth understanding of basic AAV biology and develop better gene therapies for rare and also common diseases. The consortium aims to develop a standard set of analytic tests to improve the production and functional assessment of AAVs and therapeutic genes. Such tests will be broadly applicable and will bring the needed manufacturing efficiency required for developing gene therapies for very rare conditions.

The BGTC also will work toward bringing therapies sooner to individuals in need. To start, BGTC-funded research will support four to six clinical trials, each focused on a distinct rare disease. While the details haven’t yet been decided, these diseases are expected to be rare, single-gene diseases that lack gene therapies or commercial programs in development, despite having substantial groundwork in place to enable the rapid initiation of preclinical and clinical studies.

Through these trials, the BGTC will chart a path from studies in animal models of disease to human clinical trials that cuts years off the development process. This will include exploring methods to streamline regulatory requirements and processes for FDA approval of safe and effective gene therapies, including developing standardized approaches to preclinical testing.

This work promises to be a significant investment in helping people with rare diseases. The NIH and private partners will contribute approximately $76 million over five years to support BGTC-funded projects. This includes about $39.5 million from the participating NIH institutes and centers, pending availability of funds. The NCATS, which is NIH’s lead for BGTC, is expected to contribute approximately $8 million over five years.

Today, only two rare inherited conditions have FDA-approved gene therapies. The hope is this investment will raise that number and ultimately reduce the many significant challenges, including health care costs, faced by families that have a loved one with a rare disease. In fact, a recent study found that health care costs for people with a rare disease are three to five times greater than those for people without a rare disease [2]. These families need help, and BGTC offers an encouraging new way forward for them.

References:

[1] NIH, FDA and 15 private organizations join forces to increase effective gene therapies for rare diseases. NIH news release, October 27, 2021.

[2] The IDeaS initiative: pilot study to assess the impact of rare diseases on patients and healthcare systems. Tisdale, A., Cutillo, C.M., Nathan, R. et al. Orphanet J Rare Dis 16, 429 (2021).

Links:

FAQ About Rare Diseases (National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences/NIH)

Bespoke Gene Therapy Consortium (BGTC)

Platform Vector Gene Therapy (NCATS)

Accelerating Medicines Partnership® (AMP®) (NIH)

NIH Support: National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences; Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development; National Eye Institute; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; National Human Genome Research Institute; National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases; National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research; National Institute of Mental Health; National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke; National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders; and NIH’s BRAIN Initiative.

Share this:

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Telegram (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window)

- Click to print (Opens in new window)

Posted In: News

Tags: AAV-mediated gene delivery, AAV9, Accelerating Medicines Partnership, adeno-associated virus, AMP, AMP BGTC, bespoke gene therapies, Bespoke Gene Therapy Consortium, BGTC, children, clinical trials, FDA, gene therapy, genetic, PaVE-GT, pharmaceutical industry, pilot study, Platform Vector Gene Therapy, rare diseases, vector

Antibody Makes Alzheimer’s Protein Detectable in Blood

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Caption: The protein tau (green) aggregates abnormally in a brain cell (blue). Tau spills out of the cell and enters the bloodstream (red). Research shows that antibodies (blue) can capture tau in the blood that reflect its levels in the brain.

Credit: Sara Moser

Age can bring moments of forgetfulness. It can also bring concern that the forgetfulness might be a sign of early Alzheimer’s disease. For those who decide to have it checked out, doctors are likely to administer brief memory exams to assess the situation, and medical tests to search for causes of memory loss. Brain imaging and spinal taps can also help to look for signs of the disease. But an absolutely definitive diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease is only possible today by examining a person’s brain postmortem. A need exists for a simple, less-invasive test to diagnose Alzheimer’s disease and similar neurodegenerative conditions in living people, perhaps even before memory loss becomes obvious.

One answer may lie in a protein called tau, which accumulates in abnormal tangles in the brains of people with Alzheimer’s disease and other “tauopathy” disorders. In recent years, researchers have been busy designing an antibody to target tau in hopes that this immunotherapy approach might slow or even reverse Alzheimer’s devastating symptoms, with promising early results in mice [1, 2]. Now, an NIH-funded research team that developed one such antibody have found it might also open the door to a simple blood test [3].

Share this:

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Telegram (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window)

- Click to print (Opens in new window)

Tags: Accelerating Medicines Partnership, aging brain, Alzheimer's, Alzheimer's blood test, Alzheimer’s disease, AMP-AD, AMP-AD Biomarkers Project, antibody, blood test, brain, chronic traumatic encephalopathy, CTE, immunotherapy, neurodegenerative disorders, progressive supranuclear palsy, tau, tau imaging, tau protein, tau tangle, tauopathy

International “Big Data” Study Offers Fresh Insights into T2D

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

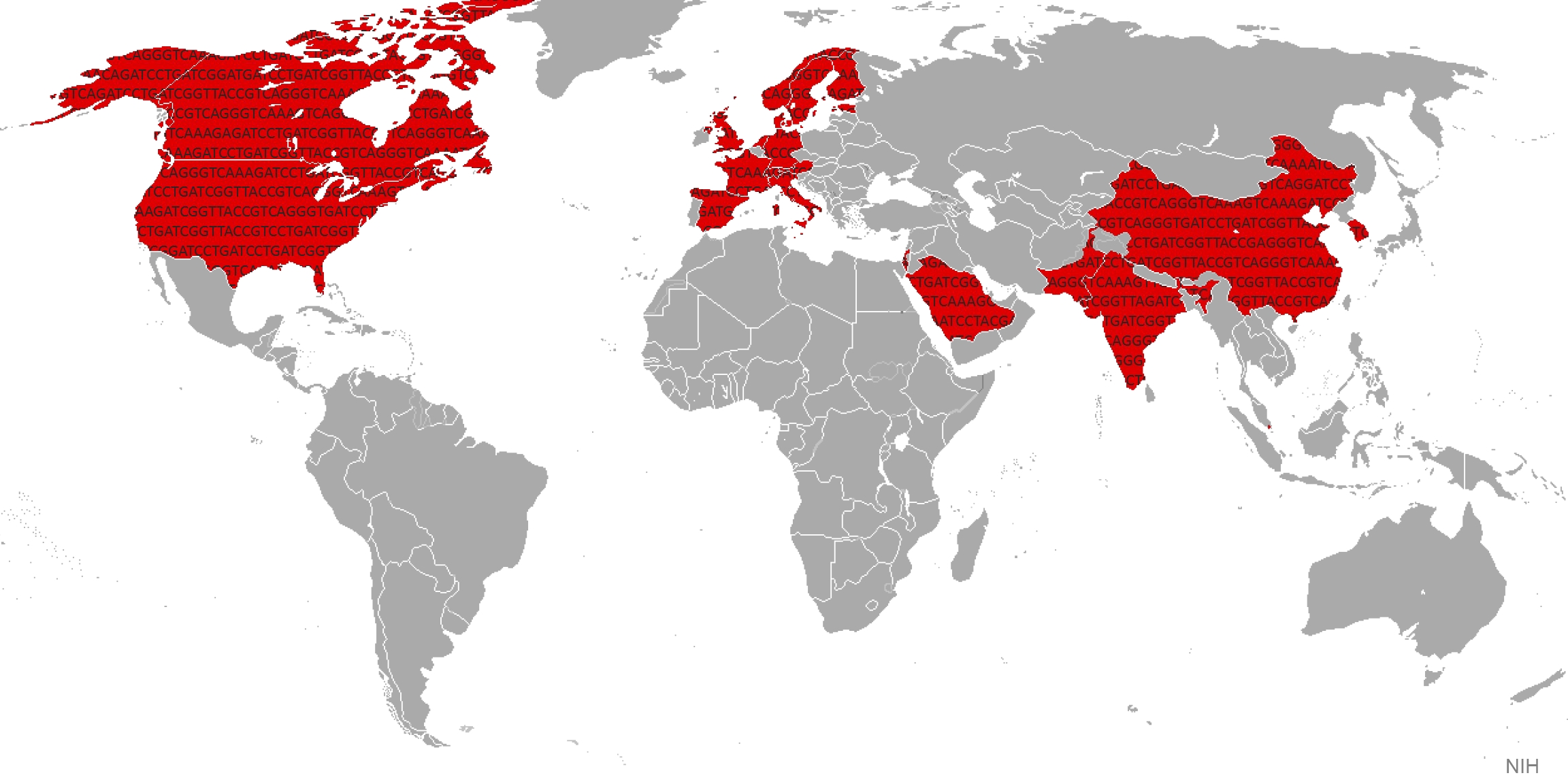

It’s estimated that about 10 percent of the world’s population either has type 2 diabetes (T2D) or will develop the disease during their lives [1]. Type 2 diabetes (formerly called “adult-onset”) happens when the body doesn’t produce or use insulin properly, causing glucose levels to rise. While diet and exercise are critical contributory factors to this potentially devastating disease, genetic factors are also important. In fact, over the last decade alone, studies have turned up more than 80 genetic regions that contribute to T2D risk, with much more still to be discovered.

Now, a major international effort, which includes work from my own NIH intramural research laboratory, has published new data that accelerate understanding of how a person’s genetic background contributes to T2D risk. The new study, reported in Nature and unprecedented in its investigative scale and scope, pulled together the largest-ever inventory of DNA sequence changes involved in T2D, and compared their distribution in people from around the world [2]. This “Big Data” strategy has already yielded important new insights into the biology underlying the disease, some of which may yield novel approaches to diabetes treatment and prevention.

The study, led by Michael Boehnke at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Mark McCarthy at the University of Oxford, England, and David Altshuler, until recently at the Broad Institute, Cambridge, MA, involved more than 300 scientists in 22 countries.

Share this:

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Telegram (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window)

- Click to print (Opens in new window)

Tags: Accelerating Medicines Partnership, AMP, big data, common variants, diabetes, exome, exome sequencing, fatty liver disease, gene variants, genetic complexity, genetic risk, genetics, genomics, genotype, GoT2D Consortium, GWAS, international collaboration, rare mutations, T2D, T2D-GENES Consortium, TM6SF2, type 2 diabetes, whole genome sequencing

Alzheimer’s Disease: Tau Protein Predicts Early Memory Loss

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

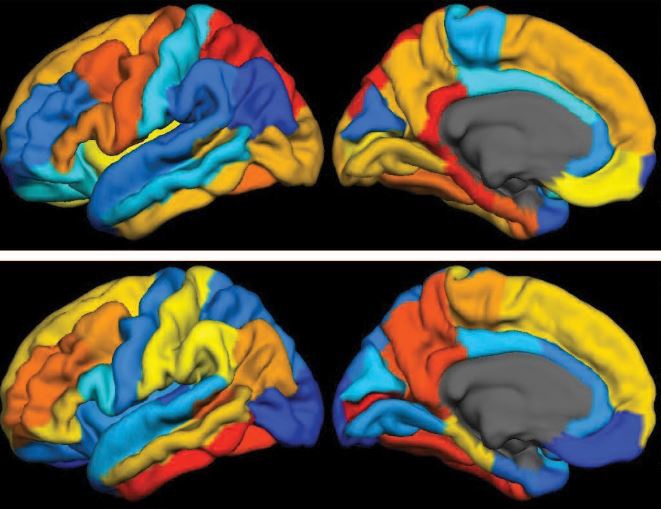

Caption: PET scan images show distribution of tau (top panel) and beta-amyloid (bottom panel) across a brain with early Alzheimer’s disease. Red indicates highest levels of protein binding, dark blue the lowest, yellows and oranges indicate moderate binding.

Credit: Brier et al., Sci Transl Med

In people with Alzheimer’s disease, changes in the brain begin many years before the first sign of memory problems. Those changes include the gradual accumulation of beta-amyloid peptides and tau proteins, which form plaques and tangles that are considered hallmarks of the disease. While amyloid plaques have received much attention as an early indicator of disease, until very recently there hadn’t been any way during life to measure the buildup of tau protein in the brain. As a result, much less is known about the timing and distribution of tau tangles and its relationship to memory loss.

Now, in a study published in Science Translational Medicine, an NIH-supported research team has produced some of the first maps showing where tau proteins build up in the brains of people with early Alzheimer’s disease [1]. The new findings suggest that while beta-amyloid remains a reliable early sign of Alzheimer’s disease, tau may be a more informative predictor of a person’s cognitive decline and potential response to treatment.

Share this:

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Telegram (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window)

- Click to print (Opens in new window)

Tags: Accelerating Medicines Partnership, age-related memory loss, aging, Alzheimer’s disease, AMP, AMP-AD, ß-amyloid, beta amyloid, brain, brain scan, cerebral cortex, cognitive decline, dementia, early Alzheimer's disease, frontal lobe, imaging, memory, memory loss, neurological disease, neurology, parietal lobe, PET scans, tau, tau protein, temporal lobe, translational medicine

DNA Analysis Finds New Target for Diabetes Drugs

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Type 2 diabetes (T2D) tends to run in families, and over the last five years the application of genomic technologies has led to discovery of more than 60 specific DNA variants that contribute to risk. My own research laboratory at NIH has played a significant role in this adventure. But this approach doesn’t just provide predictions of risk; it may also provide a path to developing new ways of treating and preventing this serious, chronic disease that affects about 26 million Americans.

In an unprecedented effort aimed at finding and validating new therapeutic targets for T2D, an international team led by NIH-funded researchers recently analyzed the DNA of about 150,000 people across five different ancestry groups. Their work uncovered a set of 12 rare mutations in the SLC30A8 gene that appear to provide powerful protection against T2D, reducing risk about 65 percent—even in the face of obesity and other risk factors for the disease [1].

Share this:

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Telegram (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window)

- Click to print (Opens in new window)

Introducing AMP: The Accelerating Medicines Partnership

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

It would seem like there’s never been a better time for drug development. Recent advances in genomics, proteomics, imaging, and other technologies have led to the discovery of more than a thousand risk factors for common diseases—biological changes that ought to hold promise as targets for drugs.

But this deluge of new opportunities has to be put in context: drug development is a terribly difficult business. To the dismay of researchers, drug companies, and patients alike, the vast majority of drugs entering the development pipeline fall by the wayside. The most distressing failures occur when a drug is found to be ineffective in the later stages of development—in Phase II or Phase III clinical studies—after years of work and millions of dollars have already been spent [1]. Why is this happening? One major reason is that we’re not selecting the right biological changes to target from the start.

Share this:

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Telegram (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window)

- Click to print (Opens in new window)