translational medicine

Rice-Sized Device Tests Brain Tumor’s Drug Responses During Surgery

Posted on by Lawrence Tabak, D.D.S., Ph.D.

Scientists have made remarkable progress in understanding the underlying changes that make cancer grow and have applied this knowledge to develop and guide targeted treatment approaches to vastly improve outcomes for people with many cancer types. And yet treatment progress for people with brain tumors known as gliomas—including the most aggressive glioblastomas—has remained slow. One reason is that doctors lack tests that reliably predict which among many therapeutic options will work best for a given tumor.

Now an NIH-funded team has developed a miniature device with the potential to change this for the approximately 25,000 people diagnosed with brain cancers in the U.S. each year [1]. When implanted into cancerous brain tissue during surgery, the rice-sized drug-releasing device can simultaneously conduct experiments to measure a tumor’s response to more than a dozen drugs or drug combinations. What’s more, a small clinical trial reported in Science Translational Medicine offers the first evidence in people with gliomas that these devices can safely offer unprecedented insight into tumor-specific drug responses [2].

These latest findings come from a Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, team led by Pierpaolo Peruzzi and Oliver Jonas. They recognized that drug-screening studies conducted in cells or tissue samples in the lab too often failed to match what happens in people with gliomas undergoing cancer treatment. Wide variation within individual brain tumors also makes it hard to predict a tumor’s likely response to various treatment options.

It led them to an intriguing idea: Why not test various therapeutic options in each patient’s tumor? To do it, they developed a device, about six millimeters long, that can be inserted into a brain tumor during surgery to deliver tiny doses of up to 20 drugs. Doctors can then remove and examine the drug-exposed cancerous tissue in the laboratory to determine each treatment’s effects. The data can then be used to guide subsequent treatment decisions, according to the researchers.

In the current study, the researchers tested their device on six study volunteers undergoing brain surgery to remove a glioma tumor. For each volunteer, the device was implanted into the tumor and remained in place for about two to three hours while surgeons worked to remove most of the tumor. Next, the device was taken out along with the last piece of a tumor at the end of the surgery for further study of drug responses.

Importantly, none of the study participants experienced any adverse effects from the device. Using the devices, the researchers collected valuable data, including how a tumor’s response changed with varying drug concentrations or how each treatment led to molecular changes in the cancerous cells.

More research is needed to better understand how use of such a device might change treatment and patient outcomes in the longer term. The researchers note that it would take more than a couple of hours to determine how treatments produce less immediate changes, such as immune responses. As such, they’re now conducting a follow-up trial to test a possible two-stage procedure, in which their device is inserted first using minimally invasive surgery 72 hours prior to a planned surgery, allowing longer exposure of tumor tissue to drugs prior to a tumor’s surgical removal.

Many questions remain as they continue to optimize this approach. However, it’s clear that such a device gives new meaning to personalized cancer treatment, with great potential to improve outcomes for people living with hard-to-treat gliomas.

References:

[1] National Cancer Institute Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program. Cancer Stat Facts: Brain and Other Nervous System Cancer.

[2] Peruzzi P et al. Intratumoral drug-releasing microdevices allow in situ high-throughput pharmaco phenotyping in patients with gliomas. Science Translational Medicine DOI: 10.1126/scitranslmed.adi0069 (2023).

Links:

Brain Tumors – Patient Version (National Cancer Institute/NIH)

Pierpaolo Peruzzi (Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA)

Jonas Lab (Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA)

NIH Support: National Cancer Institute, National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering, National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke

Body-on-a-Chip Device Predicts Cancer Drug Responses

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Researchers continue to produce impressive miniature human tissues that resemble the structure of a range of human organs, including the livers, kidneys, hearts, and even the brain. In fact, some researchers are now building on this success to take the next big technological step: placing key components of several miniature organs on a chip at once.

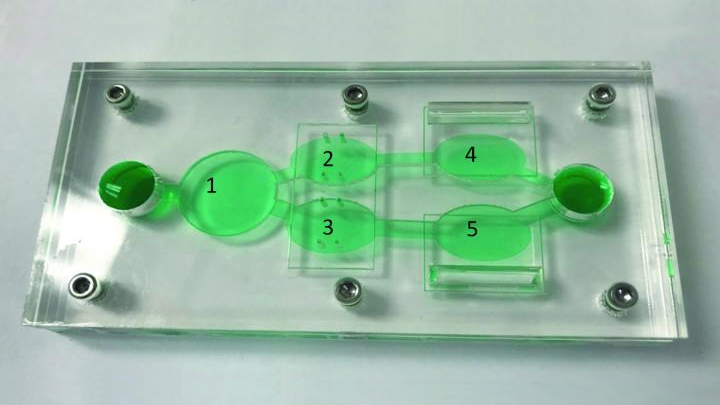

These body-on-a-chip (BOC) devices place each tissue type in its own pea-sized chamber and connect them via fluid-filled microchannels into living, integrated biological systems on a laboratory plate. In the photo above, the BOC chip is filled with green fluid to make it easier to see the various chambers. For example, this easy-to-reconfigure system can make it possible to culture liver cells (chamber 1) along with two cancer cell lines (chambers 3, 5) and cardiac function chips (chambers 2, 4).

Researchers circulate blood-mimicking fluid through the chip, along with chemotherapy drugs. This allows them to test the agents’ potential to fight human cancer cells, while simultaneously gathering evidence for potential adverse effects on tissues placed in the other chambers.

This BOC comes from a team of NIH-supported researchers, including James Hickman and Christopher McAleer, Hesperos Inc., Orlando, FL. The two were challenged by their Swiss colleagues at Roche Pharmaceuticals to create a leukemia-on-a-chip model. The challenge was to see whether it was possible to reproduce on the chip the known effects and toxicities of diclofenac and imatinib in people.

As published in Science Translational Medicine, they more than met the challenge. The researchers showed as expected that imatinib did not harm liver cells [1]. But, when treated with diclofenac, liver cells on the chip were reduced in number by about 30 percent, an observation consistent with the drug’s known liver toxicity profile.

As a second and more challenging test, the researchers reconfigured the BOC by placing a multi-drug resistant vulva cancer cell line in one chamber and, in another, a breast cancer cell line that responded to drug treatment. To explore side effects, the system also incorporated a chamber with human liver cells and two others containing beating human heart cells, along with devices to measure the cells’ electrical and mechanical activity separately.

These studies showed that tamoxifen, commonly used to treat breast cancer, indeed killed a significant number of the breast cancer cells on the BOC. But, it only did so after liver cells on the chip processed the tamoxifen to produce its more active metabolite!

Meanwhile, tamoxifen alone didn’t affect the drug-resistant vulva cancer cells on the chip, whether or not liver cells were present. This type of cancer cell has previously been shown to pump the drug out through a specific channel. Studies on the chip showed that this form of drug resistance could be overcome by adding a second drug called verapamil, which blocks the channel.

Both tamoxifen alone and the combination treatment showed some off-target effects on heart cells. While the heart cells survived the treatment, they contracted more slowly and with less force. The encouraging news was that the heart cells bounced back from the tamoxifen-only treatment within three days. But when the drug-drug combination was tested, the cardiac cells did not recover their function during the same time period.

What makes advances like this especially important is that only 1 in 10 drug candidates entering human clinical trials ultimately receives approval from the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) [2]. Often, drug candidates fail because they prove toxic to the human brain, liver, kidneys, or other organs in ways that preclinical studies in animals didn’t predict.

As BOCs are put to work in testing new drug candidates and especially treatment combinations, the hope is that we can do a better job of predicting early on which chemical compounds will prove safe and effective in humans. For those drug candidates that are ultimately doomed, “failing early” is key to reducing drug development costs. By culturing an individual patient’s cells in the chambers, BOCs also may be used to help doctors select the best treatment option for that particular patient. The ultimate goal is to accelerate the translation of basic discoveries into clinical breakthroughs. For more information about tissue chips, take a look at NIH’s Tissue Chip for Drug Screening program.

References:

[1] Multi-organ system for the evaluation of efficacy and off-target toxicity of anticancer therapeutics. McAleer CW, Long CJ, Elbrecht D, Sasserath T, Bridges LR, Rumsey JW, Martin C, Schnepper M, Wang Y, Schuler F, Roth AB, Funk C, Shuler ML, Hickman JJ. Sci Transl Med. 2019 Jun 19;11(497).

[2] Clinical development success rates for investigational drugs. Hay M, Thomas DW, Craighead JL, Economides C, Rosenthal J. Nat Biotechnol. 2014 Jan;32(1):40-51.

Links:

Tissue Chip for Drug Screening (National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences/NIH)

James Hickman (Hesperos, Inc., Orlando, FL)

NIH Support: National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences

Find and Replace: DNA Editing Tool Shows Gene Therapy Promise

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Caption: This image represents an infection-fighting cell called a neutrophil. In this artist’s rendering, the cell’s DNA is being “edited” to help restore its ability to fight bacterial invaders.

Credit: NIAID, NIH

For gene therapy research, the perennial challenge has been devising a reliable way to insert safely a working copy of a gene into relevant cells that can take over for a faulty one. But with the recent discovery of powerful gene editing tools, the landscape of opportunity is starting to change. Instead of threading the needle through the cell membrane with a bulky gene, researchers are starting to design ways to apply these tools in the nucleus—to edit out the disease-causing error in a gene and allow it to work correctly.

While the research is just getting under way, progress is already being made for a rare inherited immunodeficiency called chronic granulomatous disease (CGD). As published recently in Science Translational Medicine, a team of NIH researchers has shown with the help of the latest CRISPR/Cas9 gene-editing tools, they can correct a mutation in human blood-forming adult stem cells that triggers a common form of CGD. What’s more, they can do it without introducing any new and potentially disease-causing errors to the surrounding DNA sequence [1].

When those edited human cells were transplanted into mice, the cells correctly took up residence in the bone marrow and began producing fully functional white blood cells. The corrected cells persisted in the animal’s bone marrow and bloodstream for up to five months, providing proof of principle that this lifelong genetic condition and others like it could one day be cured without the risks and limitations of our current treatments.

Sickle Cell Disease: Gene-Editing Tools Point to Possible Ultimate Cure

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

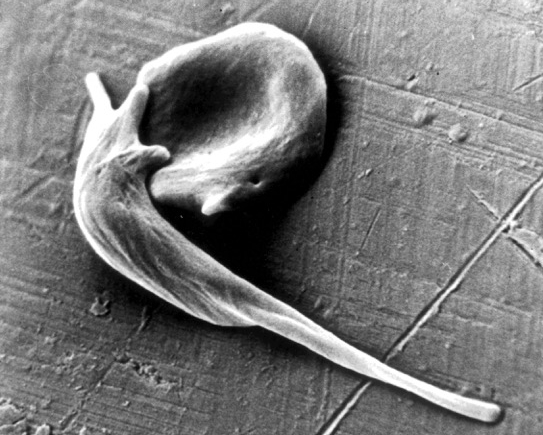

Caption: An electron micrograph showing two red blood cells deformed by crystalline hemoglobin into different “sickle” shapes characteristic of people with sickle cell disease.

Credit: Frans Kuypers: RBClab.com, UCSF Benioff Children’s Hospital Oakland

Scientists first described the sickle-shaped red blood cells that give sickle cell disease its name more than a century ago. By the 1950s, the precise molecular and genetic underpinnings of this painful and debilitating condition had become clear, making sickle cell the first “molecular disease” ever characterized. The cause is a single letter “typo” in the gene encoding oxygen-carrying hemoglobin. Red blood cells containing the defective hemoglobin become stiff, deformed, and prone to clumping. Individuals carrying one copy of the sickle mutation have sickle trait, and are generally fine. Those with two copies have sickle cell disease and face major medical challenges. Yet, despite all this progress in scientific understanding, nearly 70 years later, we still have no safe and reliable means for a cure.

Recent advances in CRISPR/Cas9 gene-editing tools, which the blog has highlighted in the past, have renewed hope that it might be possible to cure sickle cell disease by correcting DNA typos in just the right set of cells. Now, in a study published in Science Translational Medicine, an NIH-funded research team has taken an encouraging step toward this goal [1]. For the first time, the scientists showed that it’s possible to correct the hemoglobin mutation in blood-forming human stem cells, taken directly from donors, at a frequency that might be sufficient to help patients. In addition, their gene-edited human stem cells persisted for 16 weeks when transplanted into mice, suggesting that the treatment might also be long lasting or possibly even curative.

Protecting Kids: Developing a Vaccine for Respiratory Syncytial Virus

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Vaccines are one of biomedicine’s most powerful and successful tools for protecting against infectious diseases. While we currently have safe and effective vaccines to prevent measles, mumps, and a great many other common childhood diseases, we still lack a vaccine to guard against respiratory syncytial virus (RSV)—a leading cause of pneumonia among infants and young children.

Vaccines are one of biomedicine’s most powerful and successful tools for protecting against infectious diseases. While we currently have safe and effective vaccines to prevent measles, mumps, and a great many other common childhood diseases, we still lack a vaccine to guard against respiratory syncytial virus (RSV)—a leading cause of pneumonia among infants and young children.

Each year, more than 2 million U.S. children under the age of 5 require medical care for pneumonia and other potentially life-threatening lower respiratory infections caused by RSV [1,2]. Worldwide, the situation is even worse, with more than 30 million infections estimated to occur annually, most among kids in developing countries, where as many as 200,000 deaths may result [3]. So, I’m pleased to report some significant progress in biomedical research’s long battle against RSV: encouraging early results from a clinical trial of an experimental vaccine specifically designed to outwit the virus.

Big Data Study Reveals Possible Subtypes of Type 2 Diabetes

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

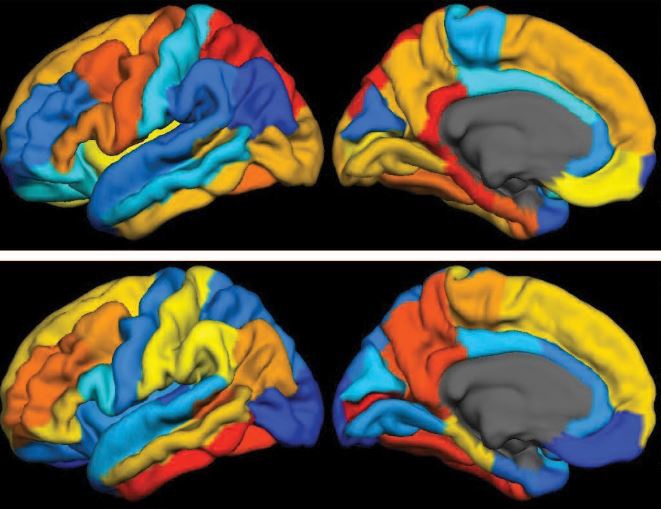

Caption: Computational model showing study participants with type 2 diabetes grouped into three subtypes, based on similarities in data contained in their electronic health records. Such information included age, gender (red/orange/yellow indicates females; blue/green, males), health history, and a range of routine laboratory and medical tests.

Credit: Dudley Lab, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York

In recent years, there’s been a lot of talk about how “Big Data” stands to revolutionize biomedical research. Indeed, we’ve already gained many new insights into health and disease thanks to the power of new technologies to generate astonishing amounts of molecular data—DNA sequences, epigenetic marks, and metabolic signatures, to name a few. But what’s often overlooked is the value of combining all that with a more mundane type of Big Data: the vast trove of clinical information contained in electronic health records (EHRs).

In a recent study in Science Translational Medicine [1], NIH-funded researchers demonstrated the tremendous potential of using EHRs, combined with genome-wide analysis, to learn more about a common, chronic disease—type 2 diabetes. Sifting through the EHR and genomic data of more than 11,000 volunteers, the researchers uncovered what appear to be three distinct subtypes of type 2 diabetes. Not only does this work have implications for efforts to reduce this leading cause of death and disability, it provides a sneak peek at the kind of discoveries that will be made possible by the new Precision Medicine Initiative’s national research cohort, which will enroll 1 million or more volunteers who agree to share their EHRs and genomic information.

An Evolving App for Genetic Tests

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Source: National Human Genome Research Institute, NIH

We all hope for health care in the genomic era to become as easy and personal as a smartphone app. And perhaps at some point it will be. At some medical centers, electronic health records already include a list of patients’ genetic variations that might trigger harmful drug reactions and send ‘pop-up’ alerts to warn the physician or pharmacist. This is just the tip of the iceberg, but it’s a harbinger of things to come. Our big challenge is to translate all the new discoveries and data from the genome project into a format that physicians and other health care providers can use to improve health.

To bridge that transition from discovery to diagnostics and treatments, the NIH launched the Genetic Testing Registry (GTR) last year. There are hundreds of genetic testing companies, thousands of genetic tests for thousands of diseases, and some diseases have more than 20 names. What a challenge for providers to sort through! GTR is becoming a central repository of all the genetic tests available, and therefore greatly simplifies this search. It’s a vital resource, as providers can’t be expected to know all the diseases and genes or to keep tabs on the growing number of tests.