CRISPR-Cas

DNA-Encoded Movie Points Way to ‘Molecular Recorder’

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Credit: Seth Shipman, Harvard Medical School, Boston

There’s a reason why our cells store all of their genetic information as DNA. This remarkable molecule is unsurpassed for storing lots of data in an exceedingly small space. In fact, some have speculated that, if encoded in DNA, all of the data ever generated by humans could fit in a room about the size of a two-car garage and, if that room happens to be climate controlled, the data would remain intact for hundreds of thousands of years! [1]

Scientists have already explored whether synthetic DNA molecules on a chip might prove useful for archiving vast amounts of digital information. Now, an NIH-funded team of researchers is taking DNA’s information storage capabilities in another intriguing direction. They’ve devised their own code to record information not on a DNA chip, but in the DNA of living cells. Already, the team has used bacterial cells to store the data needed to outline the shape of a human hand, as well the data necessary to reproduce five frames from a famous vintage film of a horse galloping (see above).

But the researchers’ ultimate goal isn’t to make drawings or movies. They envision one day using DNA as a type of “molecular recorder” that will continuously monitor events taking place within a cell, providing potentially unprecedented looks at how cells function in both health and disease.

Find and Replace: DNA Editing Tool Shows Gene Therapy Promise

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Caption: This image represents an infection-fighting cell called a neutrophil. In this artist’s rendering, the cell’s DNA is being “edited” to help restore its ability to fight bacterial invaders.

Credit: NIAID, NIH

For gene therapy research, the perennial challenge has been devising a reliable way to insert safely a working copy of a gene into relevant cells that can take over for a faulty one. But with the recent discovery of powerful gene editing tools, the landscape of opportunity is starting to change. Instead of threading the needle through the cell membrane with a bulky gene, researchers are starting to design ways to apply these tools in the nucleus—to edit out the disease-causing error in a gene and allow it to work correctly.

While the research is just getting under way, progress is already being made for a rare inherited immunodeficiency called chronic granulomatous disease (CGD). As published recently in Science Translational Medicine, a team of NIH researchers has shown with the help of the latest CRISPR/Cas9 gene-editing tools, they can correct a mutation in human blood-forming adult stem cells that triggers a common form of CGD. What’s more, they can do it without introducing any new and potentially disease-causing errors to the surrounding DNA sequence [1].

When those edited human cells were transplanted into mice, the cells correctly took up residence in the bone marrow and began producing fully functional white blood cells. The corrected cells persisted in the animal’s bone marrow and bloodstream for up to five months, providing proof of principle that this lifelong genetic condition and others like it could one day be cured without the risks and limitations of our current treatments.

Creative Minds: Modeling Neurobiological Disorders in Stem Cells

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Most neurological and psychiatric disorders are profoundly complex, involving a variety of environmental and genetic factors. Researchers around the world have worked with patients and their families to identify hundreds of possible genetic leads to learn what goes wrong in autism spectrum disorder, schizophrenia, and other conditions. The great challenge now is to begin examining this growing cache of information more systematically to understand the mechanism by which these gene variants contribute to disease risk—potentially providing important information that will someday lead to methods for diagnosis and treatment.

Meeting this profoundly difficult challenge will require a special set of laboratory tools. That’s where Feng Zhang comes into the picture. Zhang, a bioengineer at the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard, Cambridge, MA, has made significant contributions to a number of groundbreaking research technologies over the past decade, including optogenetics (using light to control brain cells), and CRISPR/Cas9, which researchers now routinely use to edit genomes in the lab [1,2].

Zhang has received a 2015 NIH Director’s Transformative Research Award to develop new tools to study multiple gene variants that might be involved in a neurological or psychiatric disorder. Zhang draws his inspiration from nature, and the microscopic molecules that various organisms have developed through the millennia to survive. CRISPR/Cas9, for instance, is a naturally occurring bacterial defense system that Zhang and others have adapted into a gene-editing tool.

Creative Minds: Can Salamanders Show Us How to Regrow Limbs?

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Jessica Whited /Credit: LightChaser Photography

Jessica Whited enjoys spending time with her 6-year-old twin boys, reading them stories, and letting their imaginations roam. One thing Whited doesn’t need to feed their curiosity about, however, is salamanders—they hear about those from Mom almost every day. Whited already has about 1,000 rare axolotl salamanders in her lab at Harvard University and Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Cambridge, MA. But caring for the 9-inch amphibians, which originate from the lakes and canals underlying Mexico City, certainly isn’t child’s play. Axolotls are entirely aquatic–their name translates to “water monster”; they like to bite each other; and they take 9 months to reach adulthood.

Like many other species of salamander, the axolotl (Ambystoma mexicanum) possesses a remarkable, almost magical, ability to grow back lost or damaged limbs. Whited’s interest in this power of limb regeneration earned her a 2015 NIH Director’s New Innovator Award. Her goal is to discover how the limbs of these salamanders know exactly where they’ve been injured and start regrowing from precisely that point, while at the same time forging vital new nerve connections to the brain. Ultimately, she hopes her work will help develop strategies to explore the possibility of “awakening” this regenerative ability in humans with injured or severed limbs.

Flipping a Genetic Switch on Obesity?

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

When weight loss is the goal, the equation seems simple enough: consume fewer calories and burn more of them exercising. But for some people, losing and keeping off the weight is much more difficult for reasons that can include a genetic component. While there are rare genetic causes of extreme obesity, the strongest common genetic contributor discovered so far is a variant found in an intron of the FTO gene. Variations in this untranslated region of the gene have been tied to differences in body mass and a risk of obesity [1]. For the one in six people of European descent born with two copies of the risk variant, the consequence is carrying around an average of an extra 7 pounds [2].

When weight loss is the goal, the equation seems simple enough: consume fewer calories and burn more of them exercising. But for some people, losing and keeping off the weight is much more difficult for reasons that can include a genetic component. While there are rare genetic causes of extreme obesity, the strongest common genetic contributor discovered so far is a variant found in an intron of the FTO gene. Variations in this untranslated region of the gene have been tied to differences in body mass and a risk of obesity [1]. For the one in six people of European descent born with two copies of the risk variant, the consequence is carrying around an average of an extra 7 pounds [2].

Now, NIH-funded researchers reporting in The New England Journal of Medicine [3] have figured out how this gene influences body weight. The answer is not, as many had suspected, in regions of the brain that control appetite, but in the progenitor cells that produce white and beige fat. The researchers found that the risk variant is part of a larger genetic circuit that determines whether our bodies burn or store fat. This discovery may yield new approaches to intervene in obesity with treatments designed to change the way fat cells handle calories.

Manipulating Microbes: New Toolbox for Better Health?

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Caption: Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron (white) living on mammalian cells in the gut (large pink cells coated in microvilli) and being activated by exogenously added compounds (small green dots) to express specific genes, such as those encoding light-generating luciferase proteins (glowing bacteria).

Credit: Janet Iwasa, Broad Visualization Group, MIT Media Lab

When you think about the cells that make up your body, you probably think about the cells in your skin, blood, heart, and other tissues and organs. But the one-celled microbes that live in and on the human body actually outnumber your own cells by a factor of about 10 to 1. Such microbes are especially abundant in the human gut, where some of them play essential roles in digestion, metabolism, immunity, and maybe even your mood and mental health. You are not just an organism. You are a superorganism!

Now imagine for a moment if the microbes that live inside our guts could be engineered to keep tabs on our health, sounding the alarm if something goes wrong and perhaps even acting to fix the problem. Though that may sound like science fiction, an NIH-funded team from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in Cambridge, MA, is already working to realize this goal. Most recently, they’ve developed a toolbox of genetic parts that make it possible to program precisely one of the most common bacteria found in the human gut—an achievement that provides a foundation for engineering our collection of microbes, or microbiome, in ways that may treat or prevent disease.

Shattering News: How Chromothripsis Cured a Rare Disease

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

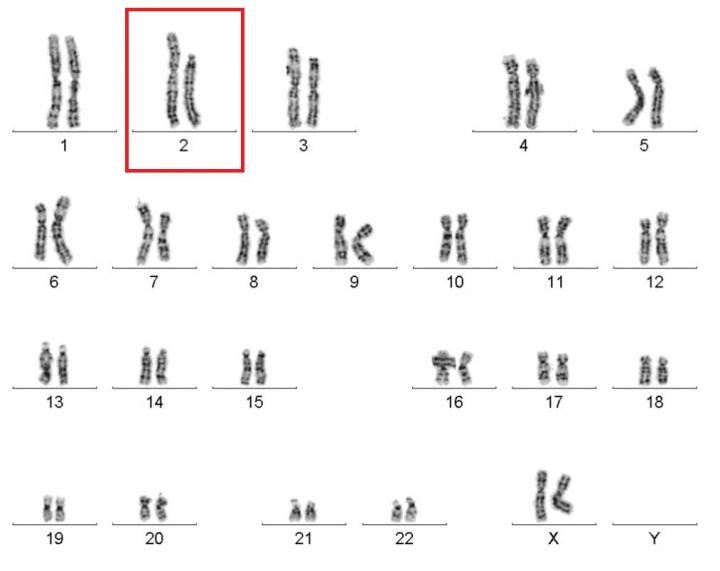

Caption: Karyotype of a woman spontaneously cured of WHIM syndrome. These chromosome pairings, which are from her white blood cells, show a normal chromosome 2 on the left, and a truncated chromosome 2 on the right.

Source: National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases , NIH

The world of biomedical research is filled with surprises. Here’s a remarkable one published recently in the journal Cell [1]. A child born in the 1950s with a rare genetic immunodeficiency syndrome amazingly cured herself years later when part of one of her chromosomes spontaneously shattered into 18 pieces during replication of a blood stem cell. The damaged chromosome randomly reassembled, sort of like piecing together a broken vase, but it was still missing a shard of 164 genes—including the very gene that caused her condition.

Researchers say the chromosomal shattering probably took place in a cell in the bone marrow. The stem cell, now without the disease-causing gene, repopulated her immune system with healthy bone marrow-derived immune cells, resulting in cure of the syndrome.

Popular Genome Editing Tool Gets Its Close-Up

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

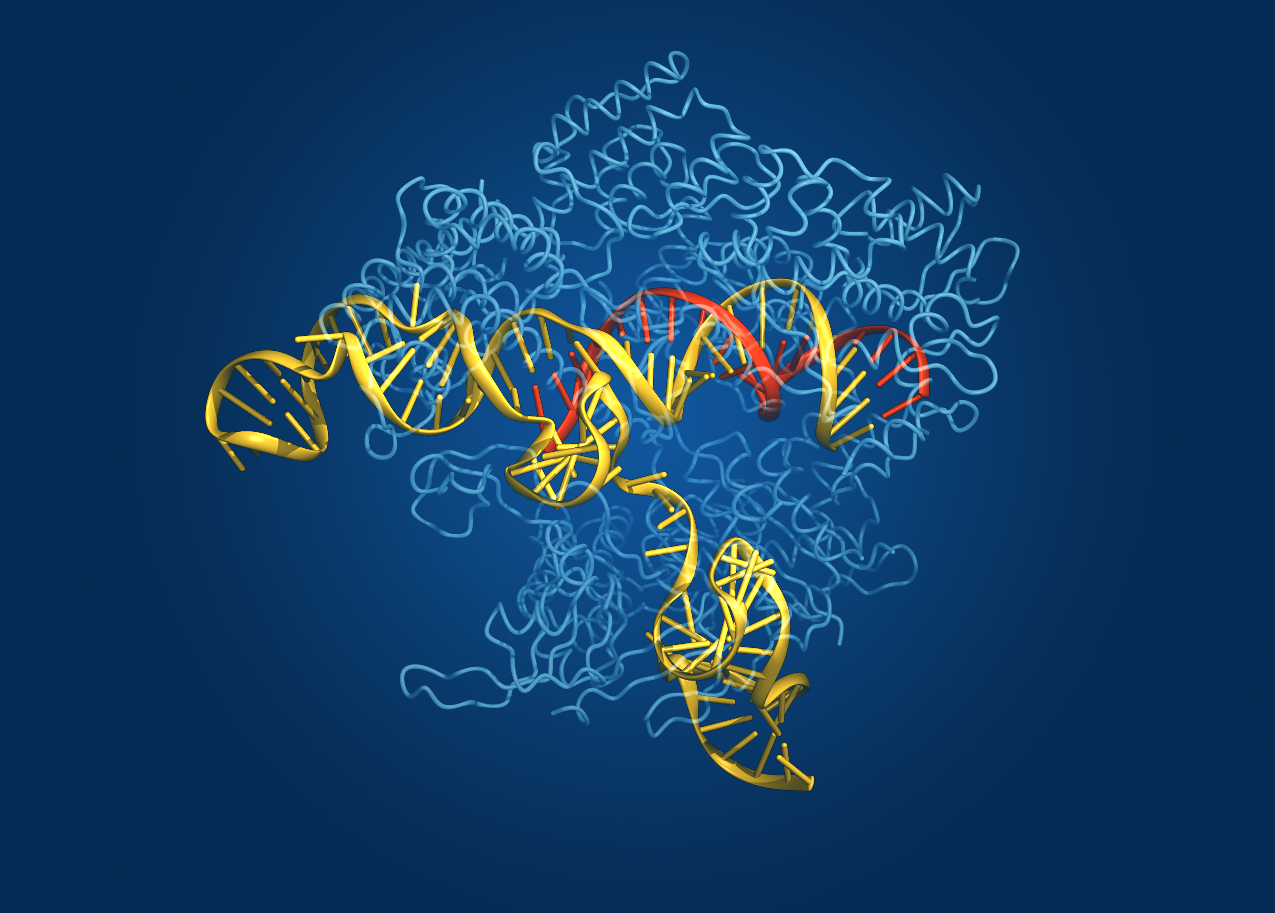

Caption: Crystal structure of the Cas9 gene-editing enzyme (light blue) in complex with an RNA guide (red) and its target DNA (yellow).

Credit: Bang Wong, Broad Institute of Harvard and MIT, Cambridge, MA

Exactly one hundred years ago, Max von Laue won the Nobel Prize in Physics for discovering that when a crystal is bombarded with X-rays, the beams bounce off the electrons surrounding the nucleus of each atom and scatter, interfering with each other (like ripples in a pond) and creating a unique pattern. These diffraction patterns could be used to decipher the arrangement of atoms in the crystal. Since then, X-ray crystallography has been used to chart a vast number of biological structures, including those of DNA, proteins, and even whole viruses.

Now, NIH-funded researchers at the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard (Cambridge, MA) have teamed up with researchers at the University of Tokyo (Japan) to use crystallography to generate a high-definition map of an innovative tool for editing genomes. Their image reveals the structure of Cas9—an enzyme with an amazing ability to slice DNA with exquisite precision—in complex with a molecule of RNA that is guiding it to a targeted region of DNA [1].

The Cas9 enzyme was originally discovered in bacteria. It’s a key part of an ancient microbial immune system, called CRISPR-Cas (Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats-Cas), that researchers recently discovered could be put to use as a tool for precisely altering DNA. This extraordinary system has been used to knock out genes in cells from bacteria, mice, and humans, and even to engineer monkeys with specific mutations that could serve as more accurate models of human disease.

Still, there’s room for improvement. Because Cas9 is rather large, Broad researcher Feng Zhang (a recipient of both the NIH Director’s Transformative Research Award and an NIH Director’s Pioneer Award) wants to trim the enzyme a bit so it could be packaged into viruses for new applications. Armed with the new crystal structure, Zhang’s team can now determine which regions of the enzyme are essential for editing DNA and which parts might be dispensable.

Another issue with Cas9 is that it occasionally makes errors, cutting the wrong region of DNA. Zhang thinks the new structural schematic of Cas9, along with the guide molecule RNA and target DNA, might point to ways in which the enzyme can be optimized to reduce the chance of errors.

Zhang’s team isn’t the only one interested in tweaking Cas9 to improve its engineering potential. A group led by Jennifer Doudna and Eva Nogales, both of the University of California, Berkeley, also recently used X-ray crystallography to generate images of two different versions of Cas9: one from Streptococcus pyogenes and the other from Actinomyces naeslundii [2]. By the way, the Foundation for the NIH recently named Doudna as the winner of its 2014 Lurie Prize in the Biomedical Sciences. The NIH grantee received the award for her pioneering role in the 2012 discovery of the CRISPR gene-editing technique.

Thanks to all of these new crystal structures, the scientific community is a step closer to realizing the full potential of Cas9/CRISPR technology to advance our understanding of disease and accelerate development of treatments and cures. So, here’s to our old friend crystallography and all of the exciting ways in which it will continue to expand our scientific horizons for years to come!

References:

[1] Crystal Structure of Cas9 in Complex with Guide RNA and Target DNA. Nishimasu H, Ran FA, Hsu PD, Konermann S, Shehata SI, Dohmae N, Ishitani R, Zhang F, Nureki O. Cell. 2014 Feb 12. pii: S0092-8674(14)00156-1.

[2] Structures of Cas9 Endonucleases Reveal RNA-Mediated Conformational Activation. Jinek M, Jiang F, Taylor DW, Sternberg SH, Kaya E, Ma E, Anders C, Hauer M, Zhou K, Lin S, Kaplan M, Iavarone AT, Charpentier E, Nogales E, Doudna JA. Science. 2014 Feb 6

Links:

Zhang Lab, Broad Institute of Harvard and MIT, Cambridge, MA

Genome Engineering Resource Center maintained by the Zhang Lab

Nureki Lab, Department of Biophysics and Biochemistry, The University of Tokyo

Doudna Lab, University of California, Berkeley, CA

Foundation for the NIH to Award Lurie Prize in Biomedical Sciences to Jennifer Doudna from UC Berkeley, 25 February 2014

The Nogales Lab, University of California, Berkeley, CA

NIH Director’s Pioneer Award. (NIH Common Fund)

NIH Director’s Transformative Research Award. (NIH Common Fund)

NIH support: Office of the Director (Common Fund); National Institute of Mental Health; National Institute of General Medical Sciences