stem cell

Mini-Lungs in a Lab Dish Mimic Early COVID-19 Infection

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Researchers have become skilled at growing an array of miniature human organs in the lab. Such lab-grown “organoids” have been put to work to better understand diabetes, fatty liver disease, color vision, and much more. Now, NIH-funded researchers have applied this remarkable lab tool to produce mini-lungs to study SARS-CoV-2, the coronavirus that causes COVID-19.

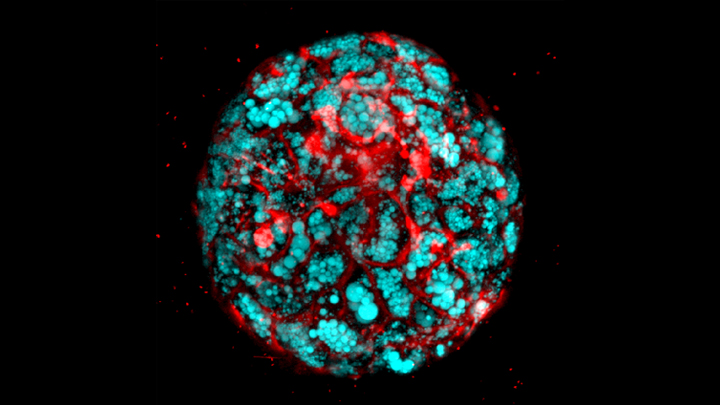

The intriguing bubble-like structures (red/clear) in the mini-lung pictured above represent developing alveoli, the tiny air sacs in our lungs, where COVID-19 infections often begin. In this organoid, the air sacs consist of many thousands of cells, all of which arose from a single adult stem cell isolated from tissues found deep within healthy human lungs. When carefully nurtured in lab dishes, those so-called alveolar epithelial type-2 cells (AT2s) begin to multiply. As they grow, they spontaneously assemble into structures that closely resemble alveoli.

A team led by Purushothama Rao Tata, Duke University School of Medicine, Durham, NC, developed these mini-lungs in a quest to understand how adult stem cells help to regenerate damaged tissue in the deepest recesses of the lungs, where SARS-CoV-2 attacks. In earlier studies, the researchers had shown it was possible for these cells to produce miniature alveoli. But there was a problem: the “soup” they used to nurture the growing cells included ingredients that weren’t well defined, making it hard to characterize the experiments fully.

In the study, now reported in Cell Stem Cell, the researchers found a way to simplify and define that brew. For the first time, they could produce mini-lungs consisting only of human lung cells. By growing them in large numbers in the lab, they can now learn more about SARS-CoV-2 infection and look for new ways to prevent or treat it.

Tata and his collaborators at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, have already confirmed that SARS-CoV-2 infects the mini-lungs via the critical ACE2 receptor, just as the virus is known to do in the lungs of an infected person.

Interestingly, the cells also produce cytokines, inflammatory molecules that have been tied to tissue damage. The findings suggest the cytokine signals may come from the lungs themselves, even before immune cells arrive on the scene.

The heavily infected lung cells eventually self-destruct and die. In an unexpected turn of events, they even induce cell death in some neighboring healthy cells that are not infected. The relevance of the studies to the clinic was boosted by the finding that the gene activity patterns in the mini-lungs are a close match to those found in samples taken from six patients with severe COVID-19.

Now that he’s got the recipe down, Tata is busy making organoids and helping to model COVID-19 infections, with the hope of identifying and testing promising new treatments. It’s clear these mini-lungs are breathing some added life into the basic study of COVID-19.

Reference:

[1] Human lung stem cell-based alveolospheres provide insights into SARS-CoV-2-mediated interferon responses and pneumocyte dysfunction. Katsura H, Sontake V, Tata A, Kobayashi Y, Edwards CE, Heaton BE, Konkimalla A, Asakura T, Mikami Y, Fritch EJ, Lee PJ, Heaton NS, Boucher RC, Randell SH, Baric RS, Tata PR. Cell Stem Cell. 2020 Oct 21:S1934-5909(20)30499-9.

Links:

Coronavirus (COVID-19) (NIH)

Tata Lab (Duke University School of Medicine, Durham, NC)

NIH Support: National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; National Institute of General Medical Sciences; National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases

Putting 3D Printing to Work to Heal Spinal Cord Injury

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

For people whose spinal cords are injured in traffic accidents, sports mishaps, or other traumatic events, cell-based treatments have emerged as a potential avenue for encouraging healing. Now, taking advantage of advances in 3D printing technology, researchers have created customized implants that may boost the power of cell-based therapies for repairing injured spinal cords.

Made of soft hydrogels that mimic spinal cord tissue, the implant pictured here measures just 2 millimeters across and is about as thick as a penny. It was specially designed to encourage healing in rats with spinal cord injuries. The tiny, open channels that surround the solid “H”-shaped core are designed to guide the growth of new neural extensions, keeping them aligned properly with the spinal cord.

When left on their own, neural cells have a tendency to grow haphazardly. But the 3D-printed implant is engineered to act as a scaffold, keeping new cells directed toward the goal of patching up the injured part of the spinal cord.

For the new work, an NIH-funded research team, led by Jacob Koffler, Wei Zhu, Shaochen Chen, and Mark Tuszynski of the University of California, San Diego (UCSD), used an innovative 3D printing technology called microscale continuous projection printing. This technology relies on a computer projection system and precisely controlled mirrors, which direct light into a solution containing photo-sensitive polymers and cells to produce the final product. Using this approach, the researchers fabricated finely detailed, rodent-sized implants in less than 2 seconds. That’s about 1,000 times faster than a traditional 3D printer!

In a study published recently in Nature Medicine, the researchers placed their custom-made implants, loaded with rat embryonic neural stem cells, into the injured spinal cords of 11 rats. Other rats with similar injuries received empty implants or stem cells without the implant. Within 5 months, rats with the cell-loaded implants had new neural cells bridging the injured area, along with spontaneous regrowth of blood vessels to feed the new neural tissue. Most importantly, they had regained use of their hind limbs. Animals receiving empty implants or cell-based therapy without an implant didn’t show that kind of recovery.

The new findings offer proof-of-principle that 3D printing technology can be used to create implants tailored to the precise shape and size of an injury. In fact, the researchers have already scaled up the process to produce 4-centimeter-sized implants to match several different, complex spinal cord injuries in humans. These implants were printed in a mere 10 minutes.

The UCSD team continues to work on further improvements, including the addition of growth factors or other ingredients that may further encourage neuron growth and functional recovery. If all goes well, the team hopes to launch human clinical trials of their cell-based treatments for spinal cord injury within a few years. And that should provide hope for the hundreds of thousands of people around the world who suffer serious spinal cord injuries each year.

Reference:

[1] Biomimetic 3D-printed scaffolds for spinal cord injury repair. Koffler J, Zhu W, Qu X, Platoshyn O, Dulin JN, Brock J, Graham L, Lu P, Sakamoto J, Marsala M, Chen S, Tuszynski MH. Nat Med. 2019 Feb;25(2):263-269.

Links:

Spinal Cord Injury Information Page (National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke/NIH)

Stem Cell Information (NIH)

Koffler Lab (University of California, San Diego)

Shaochen Chen (UCSD)

Tuszynski Lab (UCSD)

NIH Support: National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering; National Institute of Child Health and Human Development

Can Organoids Yield Answers to Fatty Liver Disease?

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

With advances in induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) technology, it’s now possible to reprogram adult skin or blood cells to form miniature human organs in a lab dish. While these “organoids” closely mimic the structures of the liver and other vital organs, it’s been tough to get them to represent inflammation, fibrosis, fat accumulation, and many other complex features of disease.

Fatty liver diseases are an increasingly serious health problem. So, I’m pleased to report that, for the first time, researchers have found a reliable way to make organoids that display the hallmarks of those conditions. This “liver in a dish” model will enable the identification and preclinical testing of promising drug targets, helping to accelerate discovery and development of effective new treatments.

Previous methods working with stem cells have yielded liver organoids consisting primarily of epithelial cells, or hepatocytes, which comprise most of the organ. Missing were other key cell types involved in the inflammatory response to fatty liver diseases.

To create a better organoid, the team led by Takanori Takebe, Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, focused its effort on patient-derived iPSCs. Takebe and his colleagues devised a special biochemical “recipe” that allowed them to grow liver organoids with sufficient cellular complexity.

As published in Cell Metabolism, the recipe involves a three-step process to coax human iPSCs into forming multi-cellular liver organoids in as little as three weeks. With careful analysis, including of RNA sequencing data, they confirmed that those organoids contained hepatocytes and other supportive cell types. The latter included Kupffer cells, which play a role in inflammation, and stellate cells, the major cell type involved in fibrosis. Fibrosis is the scarring of the liver in response to tissue damage.

Now with a way to make multi-cellular liver organoids, the researchers put them to the test. When exposed to free fatty acids, the organoids gradually accumulated fat in a dose-dependent manner and grew inflamed, which is similar to what happens to people with fatty liver diseases.

The organoids also showed telltale biochemical signatures of fibrosis. Using a sophisticated imaging method called atomic force microscopy (AFM), the researchers found as the fibrosis worsened, they could measure a corresponding increase in an organoid’s stiffness.

Next, as highlighted in the confocal microscope image above, Takebe’s team produced organoids from iPSCs derived from children with a deadly inherited form of fatty liver disease known as Wolman disease. Babies born with this condition lack an enzyme called lysosomal acid lipase (LAL) that breaks down fats, causing them to accumulate dangerously in the liver. Similarly, the miniature liver shown here is loaded with accumulated fat lipids (blue).

That brought researchers to the next big test. Previous studies had shown that LAL deficiency in kids with Wolman disease overactivates another signaling pathway, which could be suppressed by targeting a receptor known as FXR. So, in the new study, the team applied an FXR-targeted compound called FGF19, and it prevented fat accumulation in the liver organoids derived from people with Wolman disease. The organoids treated with FGF19 not only were protected from accumulating fat, but they also survived longer and had reduced stiffening, indicating a reduction in fibrosis.

These findings suggest that FGF19 or perhaps another compound that acts similarly might hold promise for infants with Wolman disease, who often die at a very early age. That’s encouraging news because the only treatment currently available is a costly enzyme replacement therapy. The findings also demonstrate a promising approach to accelerating the search for new treatments for a variety of liver diseases.

Takebe’s team is now investigating this approach for non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), a common cause of liver failure and the need for a liver transplant. The hope is that studies in organoids will lead to promising new treatments for this liver condition, which affects millions of people around the world.

Ultimately, Takebe suggests it might prove useful to grow liver organoids from individual patients with fatty liver diseases, in order to identify the underlying biological causes and test the response of those patient-specific organoids to available treatments. Such evidence could one day help doctors to select the best available treatment option for each individual patient, and bring greater precision to treating liver disease.

Reference:

[1] Modeling steatohepatitis in humans with pluripotent stem cell-derived organoids. Ouchi R, Togo S, Kimura M, Shinozawa T, Koido M, Koike H, Thompson W, Karns RA, Mayhew CN, McGrath PS, McCauley HA, Zhang RR, Lewis K, Hakozaki S, Ferguson A, Saiki N, Yoneyama Y, Takeuchi I, Mabuchi Y, Akazawa C, Yoshikawa HY, Wells JM, Takebe T. Cell Metab. 2019 May 14. pii: S1550-4131(19)30247-5.

Links:

Wolman Disease (Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center/NIH)

Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease & NASH (National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases/NIH)

Stem Cell Information (NIH)

Tissue Chip for Drug Screening (National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences/NIH)

Takebe Lab (Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center)

NIH Support: National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases

Snapshots of Life: Healing Spinal Cord Injuries

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

When someone suffers a fully severed spinal cord, it’s considered highly unlikely the injury will heal on its own. That’s because the spinal cord’s neural tissue is notorious for its inability to bridge large gaps and reconnect in ways that restore vital functions. But the image above is a hopeful sight that one day that could change.

Here, a mouse neural stem cell (blue and green) sits in a lab dish, atop a special gel containing a mat of synthetic nanofibers (purple). The cell is growing and sending out spindly appendages, called axons (green), in an attempt to re-establish connections with other nearby nerve cells.

Shattering News: How Chromothripsis Cured a Rare Disease

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

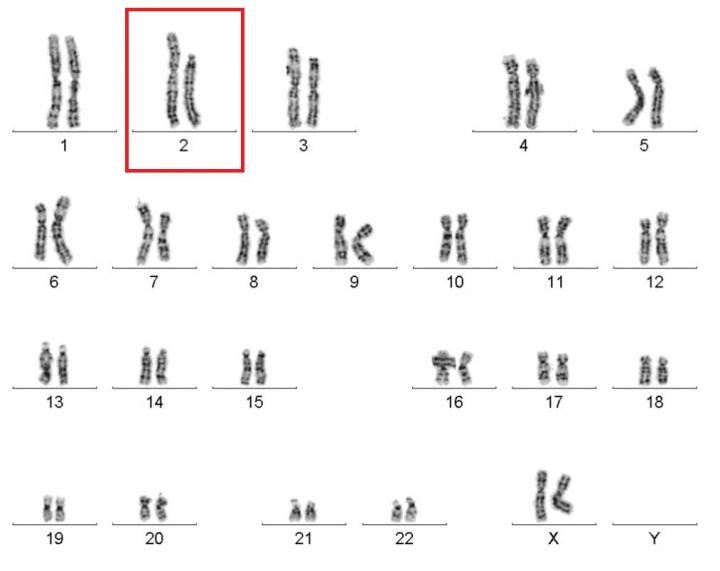

Caption: Karyotype of a woman spontaneously cured of WHIM syndrome. These chromosome pairings, which are from her white blood cells, show a normal chromosome 2 on the left, and a truncated chromosome 2 on the right.

Source: National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases , NIH

The world of biomedical research is filled with surprises. Here’s a remarkable one published recently in the journal Cell [1]. A child born in the 1950s with a rare genetic immunodeficiency syndrome amazingly cured herself years later when part of one of her chromosomes spontaneously shattered into 18 pieces during replication of a blood stem cell. The damaged chromosome randomly reassembled, sort of like piecing together a broken vase, but it was still missing a shard of 164 genes—including the very gene that caused her condition.

Researchers say the chromosomal shattering probably took place in a cell in the bone marrow. The stem cell, now without the disease-causing gene, repopulated her immune system with healthy bone marrow-derived immune cells, resulting in cure of the syndrome.

exRNA: Helping Cells Get Their Message Out

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Source: NIH Common Fund

When your email is interrupted or blocked, it creates havoc. Messages remain undelivered, stalling interactions between you and your friends, family, and colleagues at work. Likewise when communication fails between your body’s cells, disease can result. Scientists recently discovered a new group of molecules called extracellular RNA (exRNA) that appears to travel between cells to help them communicate. Now, NIH is encouraging researchers to explore the potential of these newly discovered messengers.

Why We’re So Excited About Stem Cells

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Certainly – as you can see here – stem cells are spectacularly beautiful. But they also hold spectacular promise for medicine. That’s why I immediately expressed my enthusiasm for Monday’s Supreme Court ruling that effectively enables NIH to continue conducting and funding responsible, scientifically worthy stem cell research.

There are many kinds of stem cells. This is a picture of induced pluripotent stem cells – or, iPS cells. Investigators have recently begun using iPS cells to model several neurological diseases – including Parkinson’s. The cells here have been treated with growth factors that coax them into becoming the dopamine producing (dopaminergic) neurons lost in Parkinson’s. The colorized markers indicate the presence of three proteins found within dopaminergic neurons: (1) the enzyme needed to produce dopamine (tyrosine hydroxylase, in blue), (2) a structural protein specific to neurons (Type III beta-tubulin, in green), and (3) a gene regulatory protein needed in dopaminergic neurons (FOXA2, in red). The color-mixing in some cells indicates that all three proteins are present – confirming that these cells are on their way to becoming dopaminergic neurons.

Today’s image is more than just a pretty picture. It’s a window into the ways that disease affects the body – and possibly the ways we might counter those affects. The NIH/NINDS web site has more information about how iPS cells are being used to study Parkinson’s and other neurological disorders.