coronavirus

Persistence Pays Off: Recognizing Katalin Karikó and Drew Weissman, the 2023 Nobel Prize Winners in Physiology or Medicine

Posted on by Lawrence Tabak, D.D.S., Ph.D.

Last week, biochemist Katalin Karikó and immunologist Drew Weissman earned the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for their discoveries that enabled the development of effective messenger RNA (mRNA) vaccines against COVID-19. On behalf of the NIH community, I’d like to congratulate Karikó and Weissman and thank them for their persistence in pursuing their investigations. NIH is proud to have supported their seminal research, cited by the Nobel Assembly as key publications.1,2,3

While the lifesaving benefits of mRNA vaccines are now clearly realized, Karikó and Weissman’s breakthrough finding in 2005 was not fully appreciated at the time as to why it would be significant. However, their dogged dedication to gaining a better understanding of how RNA interacts with the immune system underscores the often-underappreciated importance of incremental research. Following where the science leads through step-by-step investigations often doesn’t appear to be flashy, but it can end up leading to major advances.

To best describe Karikó and Weissman’s discovery, I’ll first do a quick review of vaccine history. As many of you know, vaccines stimulate our immune systems to protect us from getting infected or from getting very sick from a specific pathogen. Since the late 1700s, scientists have used various approaches to design effective vaccines. Some vaccines introduce a weakened or noninfectious version of a virus to the body, while others present only a small part of the virus, like a protein. The immune system detects the weak or partial virus and develops specialized defenses against it. These defenses work to protect us if we are ever exposed to the real virus.

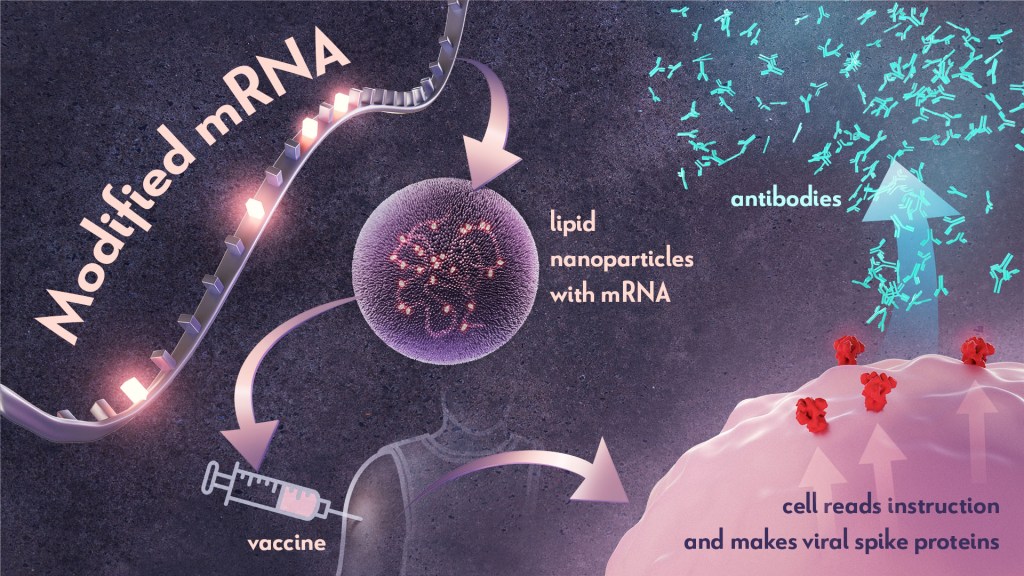

In the early 1990s, scientists began exploring a different approach to vaccines that involved delivering genetic material, or instructions, so the body’s own cells could make the virus proteins that stimulate an immune response.4,5 Because this approach eliminates the step of growing virus or virus protein in the laboratory—which can be difficult to do in very large quantities and can require a lot of time and money—it had potential, in theory, to be a faster and cheaper way to manufacture vaccines.

Scientists were exploring two types of vaccines as part of this new approach: DNA vaccines and messenger RNA (mRNA) vaccines. DNA vaccines deliver an encoded protein recipe that the cell first copies or transcribes before it starts making protein. For mRNA vaccines, the transcription process is done in the laboratory, and the vaccine delivers the “readable” instructions to the cell for making protein. However, mRNA was not immediately a practical vaccine approach due to several scientific hurdles, including that it caused inflammatory reactions that could be unhealthy for people.

Unfazed by the challenges, Karikó and Weissman spent years pursuing research on RNA and the immune system. They had a brilliant idea that they turned into a significant discovery in 2005 when they proved that inserting subtle chemical modifications to lab-transcribed mRNA eliminated the unwanted inflammatory response.1 In later studies, the pair showed that these chemical modifications also increased protein production.2,3 Both discoveries would be critical to advancing the use of mRNA-based vaccines and therapies.

Earlier theories that mRNA could enable rapid vaccine development turned out to be true. By March 2020, the first clinical trial of an mRNA vaccine for COVID-19 had begun enrolling volunteers, and by December 2020, health care workers were receiving their first shots. This unprecedented timeline was only possible because of Karikó and Weissman’s decades of work, combined with the tireless efforts of many academic, industry and government scientists, including several from the NIH intramural program. Now, researchers are exploring how mRNA could be used in vaccines for other infectious diseases and in cancer vaccines.

As an investigator myself, I’m fascinated by how science continues to build on itself—a process that is done out of the public eye. Luckily every year, the Nobel Prize briefly illuminates for the larger public this long arc of scientific discovery. The Nobel Assembly’s recognition of Karikó and Weissman is a tribute to all scientists who do the painstaking work of trying to understand how things work. Many of the tools we have today to better prevent and treat diseases would not have been possible without the brilliance, tenacity and grit of researchers like Karikó and Weissman.

References:

- K Karikó, et al. Suppression of RNA Recognition by Toll-like Receptors: The impact of nucleoside modification and the evolutionary origin of RNA. Immunity DOI: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.06.008 (2005).

- K Karikó, et al. Incorporation of pseudouridine into mRNA yields superior nonimmunogenic vector with increased translational capacity and biological stability. Molecular Therapy DOI: 10.1038/mt.2008.200 (2008).

- BR Anderson, et al. Incorporation of pseudouridine into mRNA enhances translation by diminishing PKR activation. Nucleic Acids Research DOI: 10.1093/nar/gkq347 (2010).

- DC Tang, et al. Genetic immunization is a simple method for eliciting an immune response. Nature DOI: 10.1038/356152a0 (1992).

- F Martinon, et al. Induction of virus-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes in vivo by liposome-entrapped mRNA. European Journal of Immunology DOI: 10.1002/eji.1830230749 (1993).

NIH Support:

Katalin Karikó: National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke

Drew Weissman: National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases; National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute

RECOVER: What Clinical Research Comes Next for Helping People with Long COVID

“I connected with RECOVER to be a part of the answers that I was looking for when I was at my worst.” Long COVID patient and RECOVER representative, Nitza Rochez (Bronx, NY)

People, like Nitza Rochez, who are living with Long COVID—the wide-ranging health issues that can follow an infection with SARS-CoV-2, the coronavirus that causes COVID-19—experience disabling symptoms with significant physical, emotional and financial consequences.

The NIH has been engaging and listening to Nitza and others living with Long COVID even before the start of its Researching COVID to Enhance Recovery (RECOVER) Initiative. But now, with the launch of RECOVER, patients and those with affected family or community members have joined researchers, clinicians, and experts in their efforts to unlock the mysteries of Long COVID. All have come together to understand what causes the condition, identify who is most at risk, and determine how to prevent and treat it.

RECOVER is unprecedented in its size and scope as the most-diverse, deeply characterized cohort of Long COVID patients. We’ve enlisted the help of many patient volunteers, who have enrolled in observational studies designed to help researchers learn as much as possible about people who have Long COVID.

Indeed, thousands of research participants are now providing health information and undergoing in-depth medical evaluations and tests, enabling investigators to look for trends. Additionally, studies of millions of electronic medical records are providing insights about those who have received care during the pandemic. More than 40 studies are being conducted to identify the causes of disease, potential biomarkers of Long COVID, and new therapeutic targets.

In all, RECOVER’s research assets are voluminous. They involve invaluable contributions from many people and communities, including research volunteers, research investigators, and clinical specialists. In addition, millions of health records and numerous related tissues and specimens are being analyzed for possible leads.

At the center of it all is the National Community Engagement Group (NCEG). The NCEG is comprised of people living with Long COVID and those representing others living with the condition, and it is truly instrumental to the initiative’s progress in understanding how and why SARS-CoV-2 impacts people in different ways. It’s also helping researchers learn why some people recover while others do not.

So far, we’ve learned that people hospitalized with COVID-19 are twice as likely to have Long COVID than those who were not hospitalized for infection. We’ve also learned that members of racial and ethnic minority groups with Long COVID were more likely to have been hospitalized with COVID-19.

Similarly, disparities in Long COVID exist within those living in areas with particular environmental exposures [1], and those who were already burdened by other diseases and conditions—such as diabetes and chronic pulmonary disease [2]. We’ve also discovered that the certain types of symptoms of Long COVID are consistent among patients regardless of which SARS-CoV-2 variant caused their initial infection. Yet, people infected with the earlier variants have a higher number of symptoms than those infected with more recent variants.

Patient experiences have guided and will continue to guide the study designs and trajectory of RECOVER. Now, fueled by the knowledge that we have gained, RECOVER is preparing to advance to the next phase of discovery—testing interventions in clinical trials to see if they can help people with Long COVID.

To prepare, we are beginning to identify potential clinical trial sites. This important step will help us to find the right places with the right staff and capabilities for enrolling the appropriate patient populations needed to implement the studies. We’ll ensure that the public knows when these upcoming clinical trials are ready to enroll.

Of course, the design of these RECOVER clinical trials will be critical, and insights gained from patients have been key in this process. Results from RECOVER study questionnaires, surveys, and discussions with people experiencing Long COVID identified symptom clusters considered to be the most significant and burdensome to patients. These include sleep disorders, “brain fog” (trouble thinking clearly), exercise intolerance and fatigue, and nervous system dysfunction affecting people’s ability to regulate normal body functions like heart rate and body temperature.

These patient observations have effectively guided the design of the clinical trials that will evaluate whether certain interventions and therapies can help alleviate symptoms that are part of these specific clusters. We’re excited to be advancing toward this phase of the initiative and, again, are very grateful to patient representatives like Nitza, quoted above, for getting us to this phase.

Effective evaluation of those treatments will be important, too. Early in the pandemic, while many clinical trials were launching, most were not large enough or did not have the appropriate objectives to define effective treatments for acute COVID-19. This left clinicians with few clear options when faced with patients needing help.

Learning from this experience, the RECOVER trials will be harmonized to ensure coordinated and efficient evaluation of interventions—in other words, all potential therapies will be using the same protocols platforms and the same data elements. This consistency accelerates our understanding and strengthens the certainty of findings.

Given the widespread and diverse impact that the virus has on the body, it is highly likely that more than one treatment will be needed for each kind of patient experience. Finding solutions for everyone—people of all races, ethnicities, genders, ages, and geographic locations—is paramount.

RECOVER patient representative, Juan Lewis, of San Antonio shared with us, “In April 2020, I was fighting for my life, and today I fight for my quality of life. COVID impacted me physically, mentally, socially, and financially.”

For people like Juan who are experiencing debilitating Long COVID symptoms, we know that finding answers as quickly as possible is critical. As we look ahead to the next 12 months, we’ll continue the studies evaluating the underlying causes, risk factors, and outcomes of Long Covid, and we anticipate significant scientific progress on research leading to Long COVID treatments.

Keep an eye on the RECOVER website for updates on our progress, and published findings.

References:

[1] Identifying environmental risk factors for post-acute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection: An EHR-based cohort study from the recover program. Zhang Y, Hu H, Fokaidis V, V CL, Xu J, Zang C, Xu Z, Wang F, Koropsak M, Bian J, Hall J, Rothman RL, Shenkman EA, Wei WQ, Weiner MG, Carton TW, Kaushal R. Environ Adv. 2023 Apr;11:100352.

[2] Identifying who has long COVID in the USA: a machine learning approach using N3C data. Pfaff ER, Girvin AT, Bennett TD, Bhatia A, Brooks IM, Deer RR, Dekermanjian JP, Jolley SE, Kahn MG, Kostka K, McMurry JA, Moffitt R, Walden A, Chute CG, Haendel MA; N3C Consortium. Lancet Digit Health. 2022 Jul;4(7):e532-e541.

Links:

RECOVER: Researching COVID to Enhance Recovery

Long COVID: Ask NIH Leader about Latest Research (YouTube)

NIH Builds Large Nationwide Study Population of Tens of Thousands to Support Research on Long-Term Effects of COVID-19, NIH News Release, September 15, 2021

Understanding Long-Term COVID-19 Symptoms and Enhancing Recovery, NIH Director’s Blog, October 4, 2022.

NIH RECOVER Research Identifies Potential Long COVID Disparities. NIH News Release, February 16, 2023.

NIH RECOVER Listening Session, June 2021 (NIH Videocast)

NIH RECOVER Listening Session: Understanding Long COVID Across Communities of Color and Those Hardest Hit by COVID, January 21, 2022 (NIH Videocast)

Note: Dr. Lawrence Tabak, who performs the duties of the NIH Director, has asked the heads of NIH’s Institutes, Centers, and Offices to contribute occasional guest posts to the blog to highlight some of the interesting science that they support and conduct. This is the 25th in the series of NIH guest posts that will run until a new permanent NIH director is in place.

Experimental mRNA Vaccine May Protect Against All 20 Influenza Virus Subtypes

Posted on by Lawrence Tabak, D.D.S., Ph.D.

Flu season is now upon us, and protecting yourself and loved ones is still as easy as heading to the nearest pharmacy for your annual flu shot. These vaccines are formulated each year to protect against up to four circulating strains of influenza virus, and they generally do a good job of this. What they can’t do is prevent future outbreaks of more novel flu viruses that occasionally spill over from other species into humans, thereby avoiding a future influenza pandemic.

On this latter and more-challenging front, there’s some encouraging news that was published recently in the journal Science [1]. An NIH-funded team has developed a unique “universal flu vaccine” that, with one seasonal shot, that has the potential to build immune protection against any of the 20 known subtypes of influenza virus and protect against future outbreaks.

While this experimental flu vaccine hasn’t yet been tested in people, the concept has shown great promise in advanced pre-clinical studies. Human clinical trials will hopefully start in the coming year. The researchers don’t expect that this universal flu vaccine will prevent influenza infection altogether. But, like COVID-19 vaccines, the new flu vaccine should help to reduce severe influenza illnesses and deaths when a person does get sick.

So, how does one develop a 20-in-1“multivalent” flu vaccine? It turns out that the key is the same messenger RNA (mRNA) technology that’s enabled two of the safe and effective vaccines against COVID-19, which have been so instrumental in fighting the pandemic. This includes the latest boosters from both Pfizer and Moderna, which now offer updated protection against currently circulating Omicron variants.

While this isn’t the first attempt to develop a universal flu vaccine, past attempts had primarily focused on a limited number of conserved antigens. An antigen is a protein or other substance that produces an immune response. Conserved antigens are those that tend to stay the same over time.

Because conserved antigens will look similar in many different influenza viruses, the hope was that vaccines targeting a small number of them would afford some broad influenza protection. But the focus on a strategy involving few antigens was driven largely by practical limitations. Using traditional methods to produce vaccines by growing flu viruses in eggs and isolating proteins, it simply isn’t feasible to include more than about four targets.

That’s where recent advances in mRNA technology come in. What makes mRNA so nifty for vaccines is that all you need to know is the letters, or sequence, that encodes the genetic material of a virus, including the sequences that get translated into proteins.

A research team led by Scott Hensley, Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, recognized that the ease of designing and manufacturing mRNA vaccines opened the door to an alternate approach to developing a universal flu vaccine. Rather than limiting themselves to a few antigens, the researchers could make an all-in-one influenza vaccine, encoding antigens from every known influenza virus subtype.

Influenza vaccines generally target portions of a plentiful protein on the viral surface known as hemagglutinin (H). In earlier work, Hensley’s team, in collaboration with Perelman’s mRNA vaccine pioneer Drew Weissman, showed they could use mRNA technology to produce vaccines with H antigens from single influenza viruses [2, 3]. To protect the fragile mRNA molecules that encode a selected H antigen, researchers deliver them to cells inside well-tolerated microscopic lipid shells, or nanoparticles. The same is true of mRNA COVID-19 vaccines. In their earlier studies, the researchers found that when an mRNA vaccine aimed at one flu virus subtype was given to mice and ferrets in the lab, their cells made the encoded H antigen, eliciting protective antibodies.

In this latest study, they threw antigens from all 20 known flu viruses into the mix. This included H antigens from 18 known types of influenza A and two lineages of influenza B. The goal was to develop a vaccine that could teach the immune system to recognize and respond to any of them.

More study is needed, of course, but early indications are encouraging. The vaccine generated strong and broad antibody responses in animals. Importantly, it worked both in animals with no previous immunity to the flu and in those previously infected with flu viruses. That came as good news because past infections and resulting antibodies sometimes can interfere with the development of new antibodies against related viral subtypes.

In more good news, the researchers found that vaccinated mice and ferrets were protected against severe illness when later challenged with flu viruses. Those viruses included some that were closely matched to antigens in the vaccine, along with some that weren’t.

The findings offer proof-of-principle that mRNA vaccines containing a wide range of antigens can offer broad protection against influenza and likely other viruses as well, including the coronavirus strains responsible for COVID-19. The researchers report that they’re moving toward clinical trials in people, with the goal of beginning an early phase 1 trial in the coming year. The hope is that these developments—driven in part by technological advances and lessons learned over the course of the COVID-19 pandemic—will help to mitigate or perhaps even prevent future pandemics.

References:

[1] A multivalent nucleoside-modified mRNA vaccine against all known influenza virus subtypes. Arevalo CP, Bolton MJ, Le Sage V, Ye N, Furey C, Muramatsu H, Alameh MG, Pardi N, Drapeau EM, Parkhouse K, Garretson T, Morris JS, Moncla LH, Tam YK, Fan SHY, Lakdawala SS, Weissman D, Hensley SE. Science. 2022 Nov 25;378(6622):899-904.

[2] Nucleoside-modified mRNA vaccination partially overcomes maternal antibody inhibition of de novo immune responses in mice. Willis E, Pardi N, Parkhouse K, Mui BL, Tam YK, Weissman D, Hensley SE. Sci Transl Med. 2020 Jan 8;12(525):eaav5701.

[3] Nucleoside-modified mRNA immunization elicits influenza virus hemagglutinin stalk-specific antibodies. Pardi N, Parkhouse K, Kirkpatrick E, McMahon M, Zost SJ, Mui BL, Tam YK, Karikó K, Barbosa CJ, Madden TD, Hope MJ, Krammer F, Hensley SE, Weissman D. Nat Commun. 2018 Aug 22;9(1):3361.

Links:

Understanding Flu Viruses (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta)

COVID Research (NIH)

Decades in the Making: mRNA COVID-19 Vaccines (NIH)

Video: mRNA Flu Vaccines: Preventing the Next Pandemic (Penn Medicine, Philadelphia)

Scott Hensley (Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia)

Weissman Lab (Perelman School of Medicine)

Video: The Story Behind mRNA COVID Vaccines: Katalin Karikó and Drew Weissman (Penn Medicine, Philadelphia)

NIH Support: National Institute for Allergy and Infectious Diseases

Study Shows Benefits of COVID-19 Vaccines and Boosters

Posted on by Lawrence Tabak, D.D.S., Ph.D.

As colder temperatures settle in and people spend more time gathered indoors, cases of COVID-19 and other respiratory illnesses almost certainly will rise. That’s why, along with scheduling your annual flu shot, it’s now recommended that those age 5 and up should get an updated COVID-19 booster shot [1,2]. Not only will these new boosters guard against the original strain of the coronavirus that started the pandemic, they will heighten your immunity to the Omicron variant and several of the subvariants that continue to circulate in the U.S. with devastating effects.

At last count, about 14.8 million people in the U.S.—including me—have rolled up their sleeves to receive an updated booster shot [3]. It’s a good start, but it also means that most Americans aren’t fully up to date on their COVID-19 vaccines. If you or your loved ones are among them, a new study may provide some needed encouragement to make an appointment at a nearby pharmacy or clinic to get boosted [4].

A team of NIH-supported researchers found a remarkably low incidence of severe COVID-19 illness last fall, winter, and spring among more than 1.6 million veterans who’d been vaccinated and boosted. Severe illness was also quite low in individuals without immune-compromising conditions.

These latest findings, published in the journal JAMA, come from a research group led by Dan Kelly, University of California, San Francisco. He and his team conducted their study drawing on existing health data from the Veterans Health Administration (VA) within a time window of July 2021 and May 2022.

They identified 1.6 million people who’d had a primary-care visit within the last two years and were fully vaccinated for COVID-19, which included receiving a booster shot. Almost three-quarters of those identified were 65 and older. Nearly all were male, and more than 70 percent had another pre-existing health condition that put them at greater risk of becoming seriously ill from a COVID-19 infection.

Over a 24-week follow-up period for each fully vaccinated individual, 125 per 10,000 people had a breakthrough infection. That’s about 1 percent. Just 8.9 in 10,000 fully vaccinated people—less than 0.1 percent—died or were hospitalized from COVID-19 pneumonia. Drilling down deeper into the data:

• Individuals with an immune-compromising condition had a very low rate of hospitalization or death. In this group, 39.6 per 10,000 people had a serious breakthrough infection. That translates to 0.3 percent.

• For people with other preexisting health conditions, including diabetes and heart disease, hospitalization or death totaled 0.07 percent, or 6.7 per 10,000 people.

• For otherwise healthy adults aged 65 and older, the incidence of hospitalization or death was 1.9 per 10,000 people, or 0.02 percent.

• For boosted participants 65 or younger with no high-risk conditions, hospitalization or death came to less than 1 per 10,000 people. That comes to less than 0.01 percent.

It’s worth noting that these results reflect a period when the Delta and Omicron variants were circulating, and available boosters still were based solely on the original variant. Heading into this winter, the hope is that the updated “bivalent” boosters from Pfizer and Moderna will offer even broader protection as this terrible virus continues to evolve.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention continues to recommend that everyone stay up to date with their COVID-19 vaccines. That means all adults and kids 5 and older are encouraged to get boosted if it has been at least two months since their last COVID-19 vaccine dose. For older people and those with other health conditions, it’s even more important given their elevated risk for severe illness.

What if you’ve had a COVID-19 infection recently? Getting vaccinated or boosted a few months after you’ve had a COVID-19 infection will offer you even better protection in the future.

So, if you are among the millions of Americans who’ve been vaccinated for COVID-19 but are now due for a booster, don’t delay. Get yourself boosted to protect your own health and the health of your loved ones as the holidays approach.

References:

[1] CDC recommends the first updated COVID-19 booster. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. September 1, 2022.

[2] CDC expands updated COVID-19 vaccines to include children ages 5 through 11. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, October 12, 2022.

[3] COVID-19 vaccinations in the United States. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

[4] Incidence of severe COVID-19 illness following vaccination and booster with BNT162b2, mRNA-1273, and Ad26.COV2.S vaccines. Kelly JD, Leonard S, Hoggatt KJ, Boscardin WJ, Lum EN, Moss-Vazquez TA, Andino R, Wong JK, Byers A, Bravata DM, Tien PC, Keyhani S. JAMA. 2022 Oct 11;328(14):1427-1437.

Links:

COVID-19 Research (NIH)

Dan Kelly (University of California, San Francisco)

NIH Support: National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases

How COVID-19 Immunity Holds Up Over Time

Posted on by Lawrence Tabak, D.D.S., Ph.D.

More than 215 million people in the United States are now fully vaccinated against the SARS-CoV-2 virus responsible for COVID-19 [1]. More than 40 percent—more than 94 million people—also have rolled up their sleeves for an additional, booster dose. Now, an NIH-funded study exploring how mRNA vaccines are performing over time comes as a reminder of just how important it will be to keep those COVID-19 vaccines up to date as coronavirus variants continue to circulate.

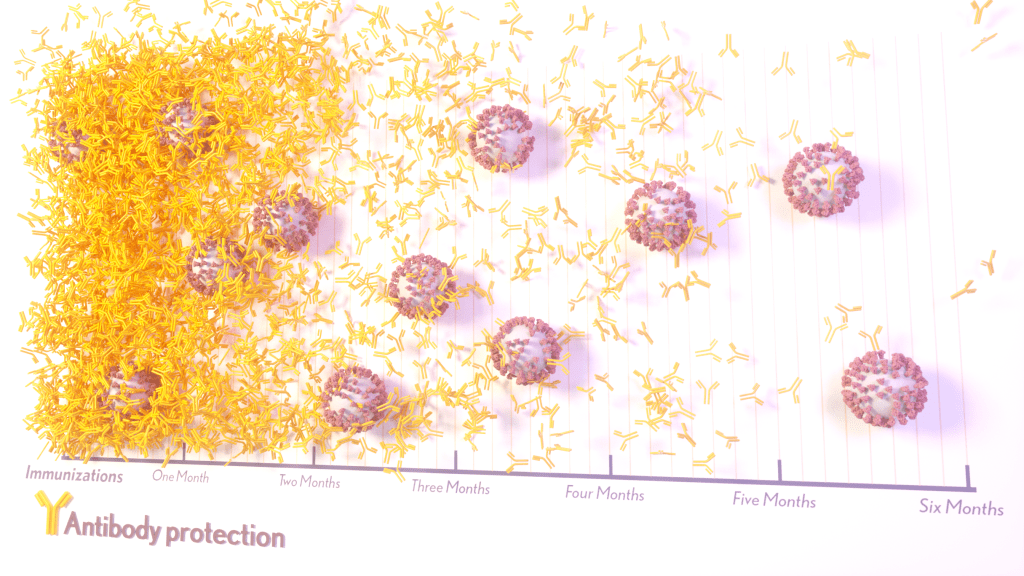

The results, published in the journal Science Translational Medicine, show that people who received two doses of either the Pfizer or Moderna COVID-19 mRNA vaccines did generate needed virus-neutralizing antibodies [2]. But levels of those antibodies dropped considerably after six months, suggesting declining immunity over time.

The data also reveal that study participants had much reduced protection against newer SARS-CoV-2 variants, including Delta and Omicron. While antibody protection remained stronger in people who’d also had a breakthrough infection, even that didn’t appear to offer much protection against infection by the Omicron variant.

The new study comes from a team led by Shan-Lu Liu at The Ohio State University, Columbus. They wanted to explore how well vaccine-acquired immune protection holds up over time, especially in light of newly arising SARS-CoV-2 variants.

This is an important issue going forward because mRNA vaccines train the immune system to produce antibodies against the spike proteins that crown the surface of the SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus. These new variants often have mutated, or slightly changed, spike proteins compared to the original one the immune system has been trained to detect, potentially dampening the immune response.

In the study, the team collected serum samples from 48 fully vaccinated health care workers at four key time points: 1) before vaccination, 2) three weeks after the first dose, 3) one month after the second dose, and 4) six months after the second dose.

They then tested the ability of antibodies in those samples to neutralize spike proteins as a correlate for how well a vaccine works to prevent infection. The spike proteins represented five major SARS-CoV-2 variants. The variants included D614G, which arose very soon after the coronavirus first was identified in Wuhan and quickly took over, as well as Alpha (B.1.1.7), Beta (B.1.351), Delta (B.1.617.2), and Omicron (B.1.1.529).

The researchers explored in the lab how neutralizing antibodies within those serum samples reacted to SARS-CoV-2 pseudoviruses representing each of the five variants. SARS-CoV-2 pseudoviruses are harmless viruses engineered, in this case, to bear coronavirus spike proteins on their surfaces. Because they don’t replicate, they are safe to study without specially designed biosafety facilities.

At any of the four time points, antibodies showed a minimal ability to neutralize the Omicron spike protein, which harbors about 30 mutations. These findings are consistent with an earlier study showing a significant decline in neutralizing antibodies against Omicron in people who’ve received the initial series of two shots, with improved neutralizing ability following an additional booster dose.

The neutralizing ability of antibodies against all other spike variants showed a dramatic decline from 1 to 6 months after the second dose. While there was a marked decline over time after both vaccines, samples from health care workers who’d received the Moderna vaccine showed about twice the neutralizing ability of those who’d received the Pfizer vaccine. The data also suggests greater immune protection in fully vaccinated healthcare workers who’d had a breakthrough infection with SARS-CoV-2.

In addition to recommending full vaccination for all eligible individuals, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) now recommends everyone 12 years and up should get a booster dose of either the Pfizer or Moderna vaccines at least five months after completing the primary series of two shots [3]. Those who’ve received the Johnson & Johnson vaccine should get a booster at least two months after receiving the initial dose.

While plenty of questions about the durability of COVID-19 immunity over time remain, it’s clear that the rapid deployment of multiple vaccines over the course of this pandemic already has saved many lives and kept many more people out of the hospital. As the Omicron threat subsides and we start to look forward to better days ahead, it will remain critical for researchers and policymakers to continually evaluate and revise vaccination strategies and recommendations, to keep our defenses up as this virus continues to evolve.

References:

[1] COVID-19 vaccinations in the United States. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. February 27, 2022.

[2] Neutralizing antibody responses elicited by SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccination wane over time and are boosted by breakthrough infection. Evans JP, Zeng C, Carlin C, Lozanski G, Saif LJ, Oltz EM, Gumina RJ, Liu SL. Sci Transl Med. 2022 Feb 15:eabn8057.

[3] COVID-19 vaccine booster shots. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Feb 2, 2022.

Links:

COVID-19 Research (NIH)

Shan-Lu Liu (The Ohio State University, Columbus)

NIH Support: National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases; National Cancer Institute; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development

‘Decoy’ Protein Works Against Multiple Coronavirus Variants in Early Study

Posted on by Lawrence Tabak, D.D.S., Ph.D.

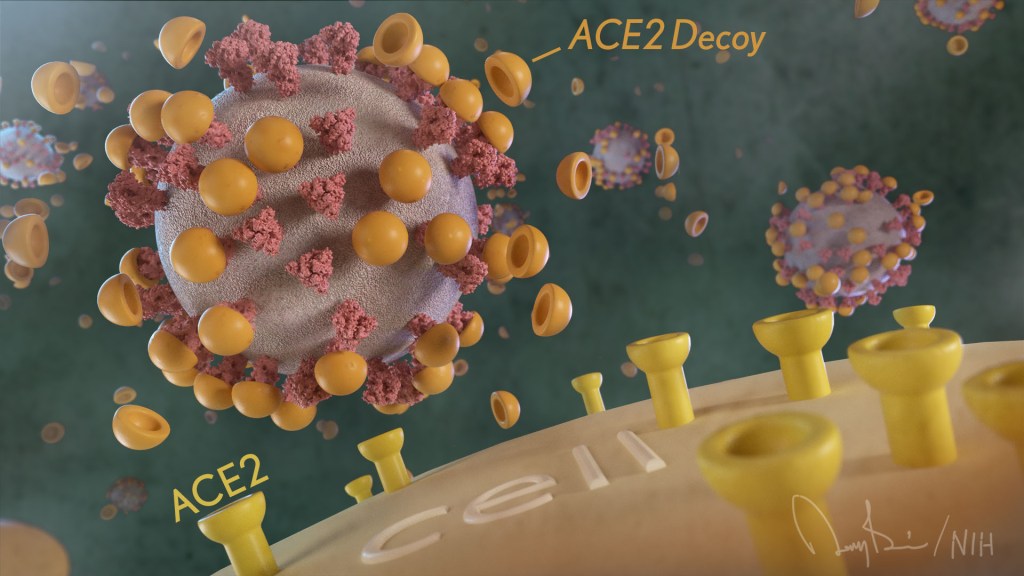

The NIH continues to support the development of some very innovative therapies to control SARS-CoV-2, the coronavirus that causes COVID-19. One innovative idea involves a molecular decoy to thwart the coronavirus.

How’s that? The decoy is a specially engineered protein particle that mimics the 3D structure of the ACE2 receptor, a protein on the surface of our cells that the virus’s spike proteins bind to as the first step in causing an infection.

The idea is when these ACE2 decoys are administered therapeutically, they will stick to the spike proteins that crown the coronavirus (see image above). With its spikes covered tightly in decoy, SARS-CoV-2 has a more-limited ability to attach to the real ACE2 and infect our cells.

Recently, the researchers published their initial results in the journal Nature Chemical Biology, and the early data look promising [1]. They found in mouse models of severe COVID-19 that intravenous infusion of an engineered ACE2 decoy prevented lung damage and death. Though more study is needed, the researchers say the decoy therapy could potentially be delivered directly to the lungs through an inhaler and used alone or in combination with other COVID-19 treatments.

The findings come from a research team at the University of Illinois Chicago team, led by Asrar Malik and Jalees Rehman, working in close collaboration with their colleagues at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. The researchers had been intrigued by an earlier clinical trial testing the ACE2 decoy strategy [2]. However, in this earlier attempt, the clinical trial found no reduction in mortality. The ACE2 drug candidate, which is soluble and degrades in the body, also proved ineffective in neutralizing the virus.

Rather than give up on the idea, the UIC team decided to give it a try. They engineered a new soluble version of ACE2 that structurally might work better as a decoy than the original one. Their version of ACE2, which includes three changes in the protein’s amino acid building blocks, binds the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein much more tightly. In the lab, it also appeared to neutralize the virus as well as monoclonal antibodies used to treat COVID-19.

To put it to the test, they conducted studies in mice. Normal mice don’t get sick from SARS-CoV-2 because the viral spike can’t bind well to the mouse version of the ACE2 receptor. So, the researchers did their studies in a mouse that carries the human ACE2 and develops a severe acute respiratory syndrome somewhat similar to that seen in humans with severe COVID-19.

In their studies, using both the original viral isolate from Washington State and the Gamma variant (P.1) first detected in Brazil, they found that infected mice infused with their therapeutic ACE2 protein had much lower mortality and showed few signs of severe acute respiratory syndrome. While the protein worked against both versions of the virus, infection with the more aggressive Gamma variant required earlier treatment. The treated mice also regained their appetite and weight, suggesting that they were making a recovery.

Further studies showed that the decoy bound to spike proteins from every variant tested, including Alpha, Beta, Delta and Epsilon. (Omicron wasn’t yet available at the time of the study.) In fact, the decoy bound just as well, if not better, to new variants compared to the original virus.

The researchers will continue their preclinical work. If all goes well, they hope to move their ACE2 decoy into a clinical trial. What’s especially promising about this approach is it could be used in combination with treatments that work in other ways, such as by preventing virus that’s already infected cells from growing or limiting an excessive and damaging immune response to the infection.

Last week, more than 17,500 people in the United States were hospitalized with severe COVID-19. We’ve got to continue to do all we can to save lives, and it will take lots of innovative ideas, like this ACE2 decoy, to put us in a better position to beat this virus once and for all.

References:

[1] Engineered ACE2 decoy mitigates lung injury and death induced by SARS-CoV-2 variants.

Zhang L, Dutta S, Xiong S, Chan M, Chan KK, Fan TM, Bailey KL, Lindeblad M, Cooper LM, Rong L, Gugliuzza AF, Shukla D, Procko E, Rehman J, Malik AB. Nat Chem Biol. 2022 Jan 19.

[2] Recombinant human angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (rhACE2) as a treatment for patients with COVID-19 (APN01-COVID-19). ClinicalTrials.gov.

Links:

COVID-19 Research (NIH)

Accelerating COVID-19 Therapeutic Interventions and Vaccines (NIH)

Asrar Malik (University of Illinois Chicago)

Jalees Rehman (University of Illinois Chicago)

NIH Support: National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases

How One Change to The Coronavirus Spike Influences Infectivity

Posted on by Lawrence Tabak, D.D.S., Ph.D.

Since joining NIH, I’ve held a number of different leadership positions. But there is one position that thankfully has remained constant for me: lab chief. I run my own research laboratory at NIH’s National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (NIDCR).

My lab studies a biochemical process called O-glycosylation. It’s fundamental to life and fascinating to study. Our cells are often adorned with a variety of carbohydrate sugars. O-glycosylation refers to the biochemical process through which these sugar molecules, either found at the cell surface or secreted, get added to proteins. The presence or absence of these sugars on certain proteins plays fundamental roles in normal tissue development and first-line human immunity. It also is associated with various diseases, including cancer.

Our lab recently joined a team of NIH scientists led by my NIDCR colleague Kelly Ten Hagen to demonstrate how O-glycosylation can influence SARS-CoV-2, the coronavirus that causes COVID-19, and its ability to fuse to cells, which is a key step in infecting them. In fact, our data, published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, indicate that some variants, seem to have mutated to exploit the process to their advantage [1].

The work builds on the virus’s reliance on the spike proteins that crown its outer surface to attach to human cells. Once there, the spike protein must be activated to fuse and launch an infection. That happens when enzymes produced by our own cells make a series of cuts, or cleavages, to the spike protein.

The first cut comes from an enzyme called furin. We and others had earlier evidence that O-glycosylation can affect the way furin makes those cuts. That got us thinking: Could O-glycosylation influence the interaction between furin and the spike protein? The furin cleavage area of the viral spike was indeed adorned with sugars, and their presence or absence might influence spike activation by furin.

We also noticed the Alpha and Delta variants carry a mutation that removes the amino acid proline in a specific spot. That was intriguing because we knew from earlier work that enzymes called GALNTs, which are responsible for adding bulky sugar molecules to proteins, prefer prolines near O-glycosylation sites.

It also suggested that loss of proline in the new variants could mean decreased O-glycosylation, which might then influence the degree of furin cleavage and SARS-CoV-2’s ability to enter cells. I should note that the recent Omicron variant was not examined in the current study.

After detailed studies in fruit fly and mammalian cells, we demonstrated in the original SARS-CoV-2 virus that O-glycosylation of the spike protein decreases furin cleavage. Further experiments then showed that the GALNT1 enzyme adds sugars to the spike protein and this addition limits the ability of furin to make the needed cuts and activate the spike protein.

Importantly, the spike protein change found in the Alpha and Delta variants lowers GALNT1 activity, making it easier for furin to start its activating cuts. It suggests that glycosylation of the viral spike by GALNT1 may limit infection with the original virus, and that the Alpha and Delta variant mutation at least partially overcomes this effect, to potentially make the virus more infectious.

Building on these studies, our teams looked for evidence of GALNT1 in the respiratory tracts of healthy human volunteers. We found that the enzyme is indeed abundantly expressed in those cells. Interestingly, those same cells also express the ACE2 receptor, which SARS-CoV-2 depends on to infect human cells.

It’s also worth noting here that the Omicron variant carries the very same spike mutation that we studied in Alpha and Delta. Omicron also has another nearby change that might further alter O-glycosylation and cleavage of the spike protein by furin. The Ten Hagen lab is looking into these leads to learn how this region in Omicron affects spike glycosylation and, ultimately, the ability of this devastating virus to infect human cells and spread.

Reference:

[1] Furin cleavage of the SARS-CoV-2 spike is modulated by O-glycosylation. Zhang L, Mann M, Syed Z, Reynolds HM, Tian E, Samara NL, Zeldin DC, Tabak LA, Ten Hagen KG. PNAS. 2021 Nov 23;118(47).

Links:

COVID-19 Research (NIH)

Kelly Ten Hagen (National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research/NIH)

Lawrence Tabak (NIDCR)

NIH Support: National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research

Welcoming President Biden

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Next Page