spike protein

‘Decoy’ Protein Works Against Multiple Coronavirus Variants in Early Study

Posted on by Lawrence Tabak, D.D.S., Ph.D.

The NIH continues to support the development of some very innovative therapies to control SARS-CoV-2, the coronavirus that causes COVID-19. One innovative idea involves a molecular decoy to thwart the coronavirus.

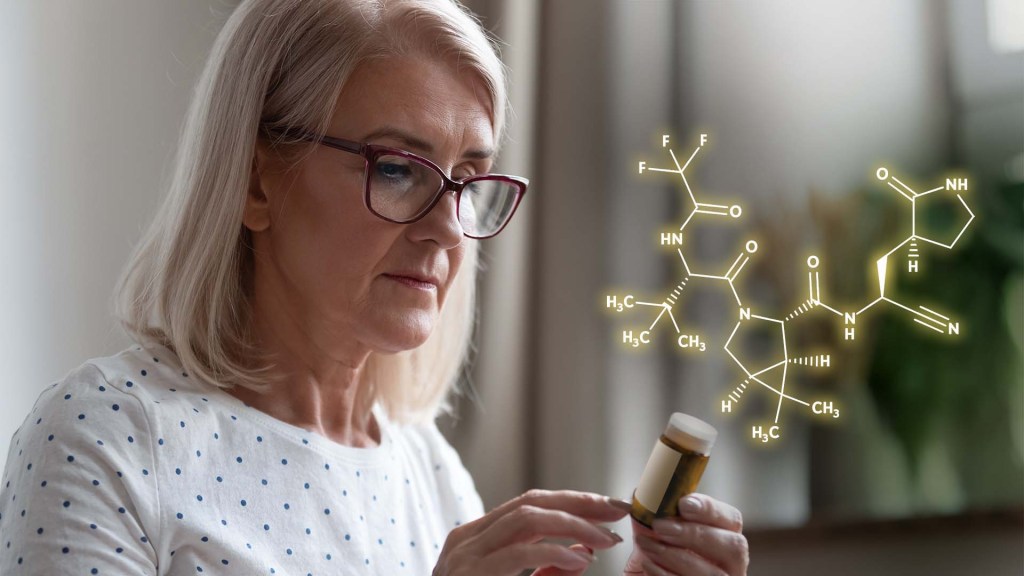

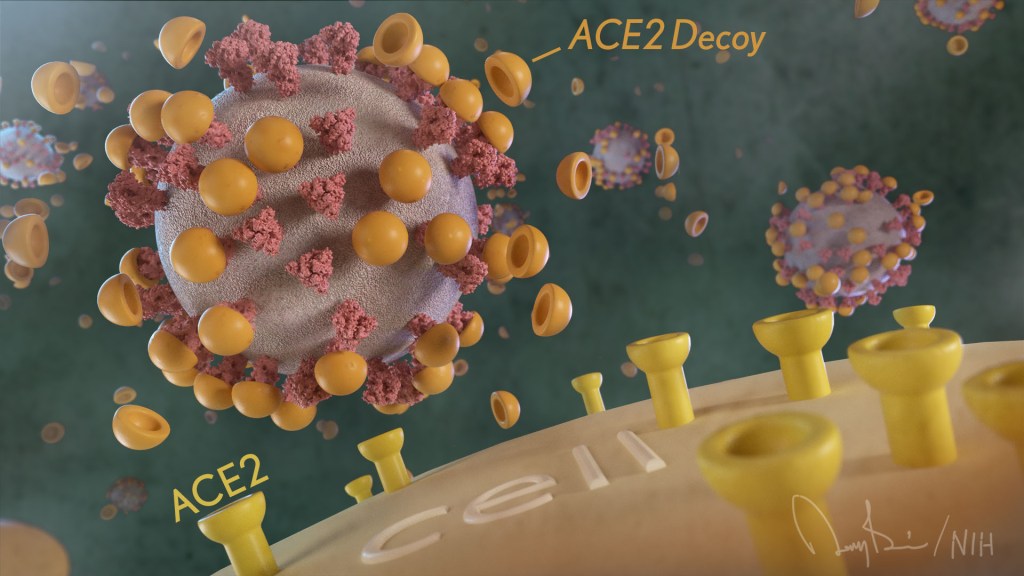

How’s that? The decoy is a specially engineered protein particle that mimics the 3D structure of the ACE2 receptor, a protein on the surface of our cells that the virus’s spike proteins bind to as the first step in causing an infection.

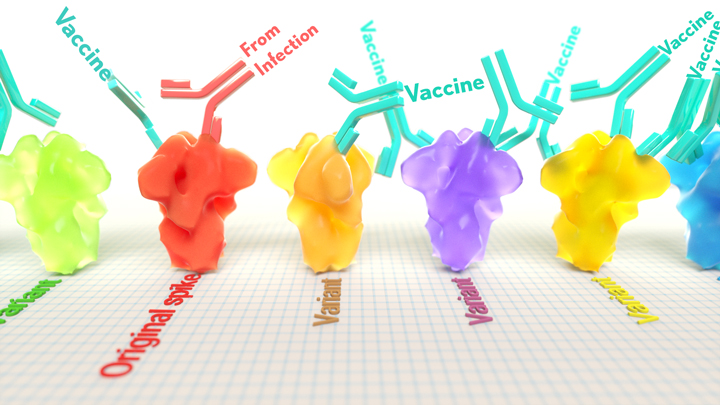

The idea is when these ACE2 decoys are administered therapeutically, they will stick to the spike proteins that crown the coronavirus (see image above). With its spikes covered tightly in decoy, SARS-CoV-2 has a more-limited ability to attach to the real ACE2 and infect our cells.

Recently, the researchers published their initial results in the journal Nature Chemical Biology, and the early data look promising [1]. They found in mouse models of severe COVID-19 that intravenous infusion of an engineered ACE2 decoy prevented lung damage and death. Though more study is needed, the researchers say the decoy therapy could potentially be delivered directly to the lungs through an inhaler and used alone or in combination with other COVID-19 treatments.

The findings come from a research team at the University of Illinois Chicago team, led by Asrar Malik and Jalees Rehman, working in close collaboration with their colleagues at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. The researchers had been intrigued by an earlier clinical trial testing the ACE2 decoy strategy [2]. However, in this earlier attempt, the clinical trial found no reduction in mortality. The ACE2 drug candidate, which is soluble and degrades in the body, also proved ineffective in neutralizing the virus.

Rather than give up on the idea, the UIC team decided to give it a try. They engineered a new soluble version of ACE2 that structurally might work better as a decoy than the original one. Their version of ACE2, which includes three changes in the protein’s amino acid building blocks, binds the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein much more tightly. In the lab, it also appeared to neutralize the virus as well as monoclonal antibodies used to treat COVID-19.

To put it to the test, they conducted studies in mice. Normal mice don’t get sick from SARS-CoV-2 because the viral spike can’t bind well to the mouse version of the ACE2 receptor. So, the researchers did their studies in a mouse that carries the human ACE2 and develops a severe acute respiratory syndrome somewhat similar to that seen in humans with severe COVID-19.

In their studies, using both the original viral isolate from Washington State and the Gamma variant (P.1) first detected in Brazil, they found that infected mice infused with their therapeutic ACE2 protein had much lower mortality and showed few signs of severe acute respiratory syndrome. While the protein worked against both versions of the virus, infection with the more aggressive Gamma variant required earlier treatment. The treated mice also regained their appetite and weight, suggesting that they were making a recovery.

Further studies showed that the decoy bound to spike proteins from every variant tested, including Alpha, Beta, Delta and Epsilon. (Omicron wasn’t yet available at the time of the study.) In fact, the decoy bound just as well, if not better, to new variants compared to the original virus.

The researchers will continue their preclinical work. If all goes well, they hope to move their ACE2 decoy into a clinical trial. What’s especially promising about this approach is it could be used in combination with treatments that work in other ways, such as by preventing virus that’s already infected cells from growing or limiting an excessive and damaging immune response to the infection.

Last week, more than 17,500 people in the United States were hospitalized with severe COVID-19. We’ve got to continue to do all we can to save lives, and it will take lots of innovative ideas, like this ACE2 decoy, to put us in a better position to beat this virus once and for all.

References:

[1] Engineered ACE2 decoy mitigates lung injury and death induced by SARS-CoV-2 variants.

Zhang L, Dutta S, Xiong S, Chan M, Chan KK, Fan TM, Bailey KL, Lindeblad M, Cooper LM, Rong L, Gugliuzza AF, Shukla D, Procko E, Rehman J, Malik AB. Nat Chem Biol. 2022 Jan 19.

[2] Recombinant human angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (rhACE2) as a treatment for patients with COVID-19 (APN01-COVID-19). ClinicalTrials.gov.

Links:

COVID-19 Research (NIH)

Accelerating COVID-19 Therapeutic Interventions and Vaccines (NIH)

Asrar Malik (University of Illinois Chicago)

Jalees Rehman (University of Illinois Chicago)

NIH Support: National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases

How One Change to The Coronavirus Spike Influences Infectivity

Posted on by Lawrence Tabak, D.D.S., Ph.D.

Since joining NIH, I’ve held a number of different leadership positions. But there is one position that thankfully has remained constant for me: lab chief. I run my own research laboratory at NIH’s National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (NIDCR).

My lab studies a biochemical process called O-glycosylation. It’s fundamental to life and fascinating to study. Our cells are often adorned with a variety of carbohydrate sugars. O-glycosylation refers to the biochemical process through which these sugar molecules, either found at the cell surface or secreted, get added to proteins. The presence or absence of these sugars on certain proteins plays fundamental roles in normal tissue development and first-line human immunity. It also is associated with various diseases, including cancer.

Our lab recently joined a team of NIH scientists led by my NIDCR colleague Kelly Ten Hagen to demonstrate how O-glycosylation can influence SARS-CoV-2, the coronavirus that causes COVID-19, and its ability to fuse to cells, which is a key step in infecting them. In fact, our data, published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, indicate that some variants, seem to have mutated to exploit the process to their advantage [1].

The work builds on the virus’s reliance on the spike proteins that crown its outer surface to attach to human cells. Once there, the spike protein must be activated to fuse and launch an infection. That happens when enzymes produced by our own cells make a series of cuts, or cleavages, to the spike protein.

The first cut comes from an enzyme called furin. We and others had earlier evidence that O-glycosylation can affect the way furin makes those cuts. That got us thinking: Could O-glycosylation influence the interaction between furin and the spike protein? The furin cleavage area of the viral spike was indeed adorned with sugars, and their presence or absence might influence spike activation by furin.

We also noticed the Alpha and Delta variants carry a mutation that removes the amino acid proline in a specific spot. That was intriguing because we knew from earlier work that enzymes called GALNTs, which are responsible for adding bulky sugar molecules to proteins, prefer prolines near O-glycosylation sites.

It also suggested that loss of proline in the new variants could mean decreased O-glycosylation, which might then influence the degree of furin cleavage and SARS-CoV-2’s ability to enter cells. I should note that the recent Omicron variant was not examined in the current study.

After detailed studies in fruit fly and mammalian cells, we demonstrated in the original SARS-CoV-2 virus that O-glycosylation of the spike protein decreases furin cleavage. Further experiments then showed that the GALNT1 enzyme adds sugars to the spike protein and this addition limits the ability of furin to make the needed cuts and activate the spike protein.

Importantly, the spike protein change found in the Alpha and Delta variants lowers GALNT1 activity, making it easier for furin to start its activating cuts. It suggests that glycosylation of the viral spike by GALNT1 may limit infection with the original virus, and that the Alpha and Delta variant mutation at least partially overcomes this effect, to potentially make the virus more infectious.

Building on these studies, our teams looked for evidence of GALNT1 in the respiratory tracts of healthy human volunteers. We found that the enzyme is indeed abundantly expressed in those cells. Interestingly, those same cells also express the ACE2 receptor, which SARS-CoV-2 depends on to infect human cells.

It’s also worth noting here that the Omicron variant carries the very same spike mutation that we studied in Alpha and Delta. Omicron also has another nearby change that might further alter O-glycosylation and cleavage of the spike protein by furin. The Ten Hagen lab is looking into these leads to learn how this region in Omicron affects spike glycosylation and, ultimately, the ability of this devastating virus to infect human cells and spread.

Reference:

[1] Furin cleavage of the SARS-CoV-2 spike is modulated by O-glycosylation. Zhang L, Mann M, Syed Z, Reynolds HM, Tian E, Samara NL, Zeldin DC, Tabak LA, Ten Hagen KG. PNAS. 2021 Nov 23;118(47).

Links:

COVID-19 Research (NIH)

Kelly Ten Hagen (National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research/NIH)

Lawrence Tabak (NIDCR)

NIH Support: National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research

Latest on Omicron Variant and COVID-19 Vaccine Protection

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

There’s been great concern about the new Omicron variant of SARS-CoV-2, the coronavirus that causes COVID-19. A major reason is Omicron has accumulated over 50 mutations, including about 30 in the spike protein, the part of the coronavirus that mRNA vaccines teach our immune systems to attack. All of these genetic changes raise the possibility that Omicron could cause breakthrough infections in people who’ve already received a Pfizer or Moderna mRNA vaccine.

So, what does the science show? The first data to emerge present somewhat encouraging results. While our existing mRNA vaccines still offer some protection against Omicron, there appears to be a significant decline in neutralizing antibodies against this variant in people who have received two shots of an mRNA vaccine.

However, initial results of studies conducted both in the lab and in the real world show that people who get a booster shot, or third dose of vaccine, may be better protected. Though these data are preliminary, they suggest that getting a booster will help protect people already vaccinated from breakthrough or possible severe infections with Omicron during the winter months.

Though Omicron was discovered in South Africa only last month, researchers have been working around the clock to learn more about this variant. Last week brought the first wave of scientific data on Omicron, including interesting work from a research team led by Alex Sigal, Africa Health Research Institute, Durban, South Africa [1].

In lab studies working with live Omicron virus, the researchers showed that this variant still relies on the ACE2 receptor to infect human lung cells. That’s really good news. It means that the therapeutic tools already developed, including vaccines, should generally remain useful for combatting this new variant.

Sigal and colleagues also tested the ability of antibodies in the plasma from 12 fully vaccinated individuals to neutralize Omicron. Six of the individuals had no history of COVID-19. The other six had been infected with the original variant in the first wave of infections in South Africa.

As expected, the samples showed very strong neutralization against the original SARS-CoV-2 variant. However, antibodies from people who’d been previously vaccinated with the two-dose Pfizer vaccine took a significant hit against Omicron, showing about a 40-fold decline in neutralizing ability.

This escape from immunity wasn’t complete. Indeed, blood samples from five individuals showed relatively good antibody levels against Omicron. All five had previously been infected with SARS-CoV-2 in addition to being vaccinated. These findings add to evidence on the value of full vaccination for protecting against reinfections in people who’ve had COVID-19 previously.

Also of great interest were the first results of the Pfizer study, which the company made available in a news release [2]. Pfizer researchers also conducted laboratory studies to test the neutralizing ability of blood samples from 19 individuals one month after a second shot compared to 20 others one month after a booster shot.

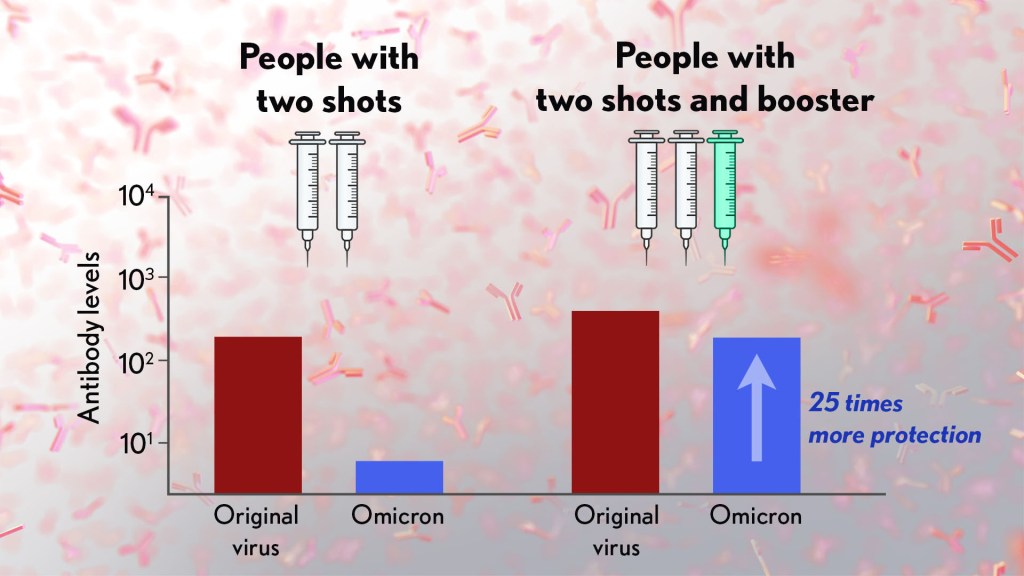

These studies showed that the neutralizing ability of samples from those who’d received two shots had a more than 25-fold decline relative to the original virus. Together with the South Africa data, it suggests that the two-dose series may not be enough to protect against breakthrough infections with the Omicron variant.

In much more encouraging news, their studies went on to show that a booster dose of the Pfizer vaccine raised antibody levels against Omicron to a level comparable to the two-dose regimen against the original variant (as shown in the figure above). While efforts already are underway to develop an Omicron-specific COVID-19 vaccine, these findings suggest that it’s already possible to get good protection against this new variant by getting a booster shot.

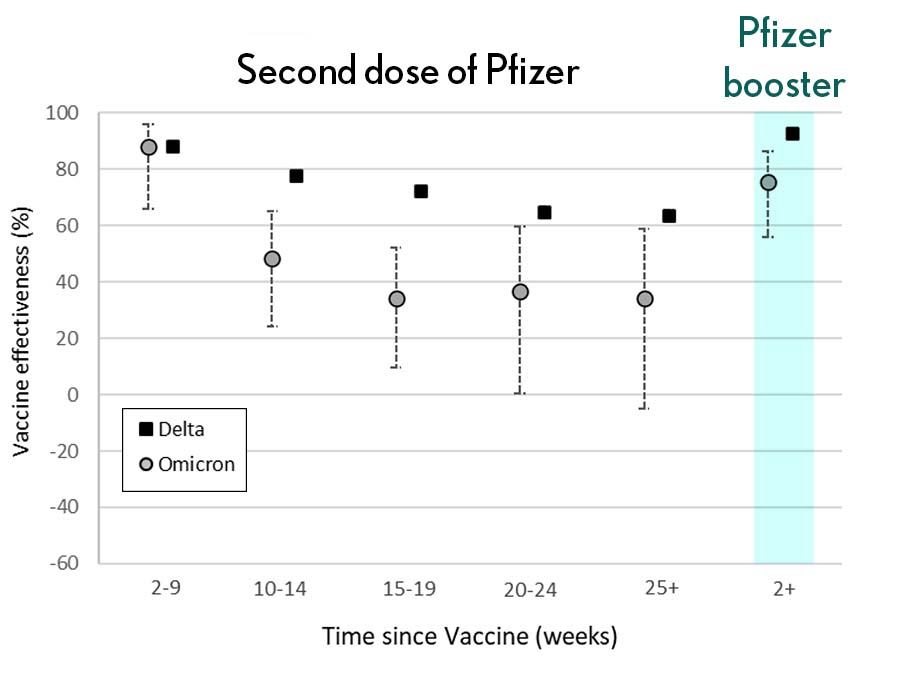

Very recently, real-world data from the United Kingdom, where Omicron cases are rising rapidly, are providing additional evidence for how boosters can help. In a preprint [3], Andrews et. al showed the effectiveness of two shots of Pfizer mRNA vaccine trended down after four months to about 40 percent. That’s not great, but note that 40 percent is far better than zero. So, clearly there is some protection provided.

Most impressively (as shown in the figure from Andrews N, et al.) a booster substantially raised that vaccine effectiveness to about 80 percent. That’s not quite as high as for Delta, but certainly an encouraging result. Once again, these data show that boosting the immune system after a pause produces enhanced immunity against new viral variants, even though the booster was designed from the original virus. Your immune system is awfully clever. You get both quantitative and qualitative benefits.

It’s also worth noting that the Omicron variant mostly doesn’t have mutations in portions of its genome that are the targets of other aspects of vaccine-induced immunity, including T cells. These cells are part of the body’s second line of defense and are generally harder for viruses to escape. While T cells can’t prevent infection, they help protect against more severe illness and death.

It’s important to note that scientists around the world are also closely monitoring Omicron’s severity While this variant appears to be highly transmissible, and it is still early for rigorous conclusions, the initial research indicates this variant may actually produce milder illness than Delta, which is currently the dominant strain in the United States.

But there’s still a tremendous amount of research to be done that could change how we view Omicron. This research will take time and patience.

What won’t change, though, is that vaccines are the best way to protect yourself and others against COVID-19. (And these recent data provide an even-stronger reason to get a booster now if you are eligible.) Wearing a mask, especially in public indoor settings, offers good protection against the spread of all SARS-CoV-2 variants. If you’ve got symptoms or think you may have been exposed, get tested and stay home if you get a positive result. As we await more answers, it’s as important as ever to use all the tools available to keep yourself, your loved ones, and your community happy and healthy this holiday season.

References:

[1] SARS-CoV-2 Omicron has extensive but incomplete escape of Pfizer BNT162b2 elicited neutralization and requires ACE2 for infection. Sandile C, et al. Sandile C, et al. medRxiv preprint. December 9, 2021.

[2] Pfizer and BioNTech provide update on Omicron variant. Pfizer. December 8, 2021.

[3] Effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines against the Omicron (B.1.1.529) variant of concern. Andrews N, et al. KHub.net preprint. December 10, 2021.

Links:

COVID-19 Research (NIH)

Sigal Lab (Africa Health Research Institute, Durban, South Africa)

Accelerating COVID-19 Vaccine Testing with ‘Correlates of Protection’

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

With Omicron now on so many people’s minds, public health officials and virologists around the world are laser focused on tracking the spread of this concerning SARS-CoV-2 variant and using every possible means to determine the effectiveness of our COVID-19 vaccines against it. Ultimately, the answer will depend on what happens in the real world. But it will also help to have a ready laboratory means for gauging how well a vaccine works, without having to wait many months for the results in the field.

With this latter idea in mind, I’m happy to share results of an NIH-funded effort to understand the immune responses associated with vaccine-acquired protection against SARS-CoV-2 [1]. The findings, based on the analysis of blood samples from more than 1,000 people who received the Moderna mRNA vaccine, show that antibody levels do correlate, albeit somewhat imperfectly, with how well a vaccine works to prevent infection.

Such measures of immunity, known as “correlates of protection,” have potential to support the approval of new or updated vaccines more rapidly. They’re also useful to show how well a vaccine will work in groups that weren’t represented in a vaccine’s initial testing, such as children, pregnant women, and those with certain health conditions.

The latest study, published in the journal Science, comes from a team of researchers led by Peter Gilbert, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle; David Montefiori, Duke University, Durham, NC; and Adrian McDermott, NIH’s Vaccine Research Center, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

The team started with existing data from the Coronavirus Efficacy (COVE) trial. This phase 3 study, conducted in 30,000 U.S. adults, found the Moderna vaccine was safe and about 94 percent effective in protecting people from symptomatic infection with SARS-CoV-2 [2].

The researchers wanted to understand the underlying immune responses that afforded that impressive level of COVID-19 protection. They also sought to develop a means to measure those responses in the lab and quickly show how well a vaccine works.

To learn more, Gilbert’s team conducted tests on blood samples from COVE participants at the time of their second vaccine dose and again four weeks later. Two of the tests measured concentrations of binding antibodies (bAbs) that latch onto spike proteins that adorn the coronavirus surface. Two others measured the concentration of more broadly protective neutralizing antibodies (nAbs), which block SARS-CoV-2 from infecting human cells via ACE2 receptors found on their surfaces.

Each of the four tests showed antibody levels that were consistently higher in vaccine recipients who did not develop COVID-19 than in those who did. That is consistent with expectations. But these data also allowed the researchers to identify the specific antibody levels associated with various levels of protection from disease.

For those with the highest antibody levels, the vaccine offered an estimated 98 percent protection. Those with levels about 1,000 times lower still were well protected, but their vaccine efficacy was reduced to about 78 percent.

Based on any of the antibodies tested, the estimated COVID-19 risk was about 10 times lower for vaccine recipients with antibodies in the top 10 percent of values compared to those with antibodies that weren’t detectable. Overall, the findings suggest that tests for antibody levels can be applied to make predictions about an mRNA vaccine’s efficacy and may be used to guide modifications to the current vaccine regimen.

To understand the significance of this finding, consider that for a two-dose vaccine like Moderna or Pfizer, a trial using such correlates of protection might generate sufficient data in as little as two months [3]. As a result, such a trial might show whether a vaccine was meeting its benchmarks in 3 to 5 months. By comparison, even a rapid clinical trial done the standard way would take at least seven months to complete. Importantly also, trials relying on such correlates of protection require many fewer participants.

Since all four tests performed equally well, the researchers say it’s conceivable that a single antibody assay might be sufficient to predict how effective a vaccine will be in a clinical trial. Of course, such trials would require subsequent real-world studies to verify that the predicted vaccine efficacy matches actual immune protection.

It should be noted that the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) would need to approve the use of such correlates of protection before their adoption in any vaccine trial. But, to date, the totality of evidence on neutralizing antibody responses as correlates of protection—for which this COVE trial data is a major contributor—is impressive.

Neutralizing antibody levels are also now being considered for use in future coronavirus vaccine trials. Indeed, for the EUA of Pfizer’s mRNA vaccine for 5-to-11-year-olds, the FDA accepted pre-specified success criteria based on neutralizing antibody responses in this age group being as good as those observed in 16- to 25-year-olds [4].

Antibody levels also have been taken into consideration for decisions about booster shots. However, it’s important to note that antibody levels are not precise enough to help in deciding whether or not any particular individual needs a COVID-19 booster. Those recommendations are based on how much time has passed since the original immunization.

Getting a booster is a really good idea heading into the holidays. The Delta variant remains very much the dominant strain in the U.S., and we need to slow its spread. Most experts think the vaccines and boosters will also provide some protection against the Omicron variant—though the evidence we need is still a week or two away. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends a COVID-19 booster for everyone ages 18 and up at least six months after your second dose of mRNA vaccine or two months after receiving the single dose of the Johnson & Johnson vaccine [5]. You may choose to get the same vaccine or a different one. And, there is a place near you that is offering the shot.

References:

[1] Immune correlates analysis of the mRNA-1273 COVID-19 vaccine efficacy clinical trial.

Gilbert PB, Montefiori DC, McDermott AB, Fong Y, Benkeser D, Deng W, Zhou H, Houchens CR, Martins K, Jayashankar L, Castellino F, Flach B, Lin BC, O’Connell S, McDanal C, Eaton A, Sarzotti-Kelsoe M, Lu Y, Yu C, Borate B, van der Laan LWP, Hejazi NS, Huynh C, Miller J, El Sahly HM, Baden LR, Baron M, De La Cruz L, Gay C, Kalams S, Kelley CF, Andrasik MP, Kublin JG, Corey L, Neuzil KM, Carpp LN, Pajon R, Follmann D, Donis RO, Koup RA; Immune Assays Team§; Moderna, Inc. Team§; Coronavirus Vaccine Prevention Network (CoVPN)/Coronavirus Efficacy (COVE) Team§; United States Government (USG)/CoVPN Biostatistics Team§. Science. 2021 Nov 23:eab3435.

[2] Efficacy and safety of the mRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2 vaccine. Baden LR, El Sahly HM, Essink B, Kotloff K, Frey S, Novak R, Diemert D, Spector SA, Rouphael N, Creech CB, McGettigan J, Khetan S, Segall N, Solis J, Brosz A, Fierro C, Schwartz H, Neuzil K, Corey L, Gilbert P, Janes H, Follmann D, Marovich M, Mascola J, Polakowski L, Ledgerwood J, Graham BS, Bennett H, Pajon R, Knightly C, Leav B, Deng W, Zhou H, Han S, Ivarsson M, Miller J, Zaks T; COVE Study Group. N Engl J Med. 2021 Feb 4;384(5):403-416.

[3] A government-led effort to identify correlates of protection for COVID-19 vaccines. Koup RA, Donis RO, Gilbert PB, Li AW, Shah NA, Houchens CR. Nat Med. 2021 Sep;27(9):1493-1494.

[4] Evaluation of the BNT162b2 Covid-19 vaccine in children 5 to 11 years of age. Walter EB, Talaat KR, Sabharwal C, Gurtman A, Lockhart S, Paulsen GC, Barnett ED, Muñoz FM, Maldonado Y, Pahud BA, Domachowske JB, Simões EAF, Sarwar UN, Kitchin N, Cunliffe L, Rojo P, Kuchar E, Rämet M, Munjal I, Perez JL, Frenck RW Jr, Lagkadinou E, Swanson KA, Ma H, Xu X, Koury K, Mather S, Belanger TJ, Cooper D, Türeci Ö, Dormitzer PR, Şahin U, Jansen KU, Gruber WC; C4591007 Clinical Trial Group. N Engl J Med. 2021 Nov 9:NEJMoa2116298.

[5] COVID-19 vaccine booster shots. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Nov 29, 2021.

Links:

COVID-19 Research (NIH)

Combat COVID (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services)

Peter Gilbert (Fred Hutchison Cancer Research Center)

David Montefiori (Duke University, Durham, NC)

Adrian McDermott (National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases/NIH)

NIH Support: National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases

New Clues to Delta Variant’s Spread in Studies of Virus-Like Particles

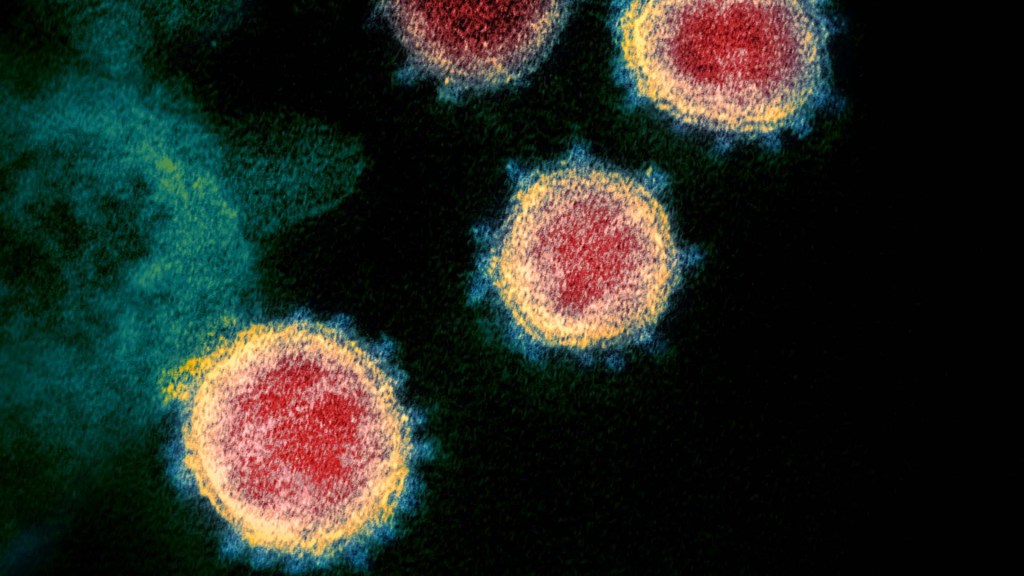

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

About 70,000 people in the United States are diagnosed with COVID-19 each and every day. It’s clear that these new cases are being driven by the more-infectious Delta variant of SARS-CoV-2, the novel coronavirus that causes COVID-19. But why does the Delta variant spread more easily than other viral variants from one person to the next?

Now, an NIH-funded team has discovered at least part of Delta’s secret, and it’s not all attributable to those widely studied mutations in the spike protein that links up to human cells through the ACE2 receptor. It turns out that a specific mutation found within the N protein coding region of the Delta genome also enables the virus to pack more of its RNA code into the infected host cell. As a result, there is increased production of fully functional new viral particles, which can go on to infect someone else.

This finding, published in the journal Science [1], comes from the lab of Nobel laureate Jennifer Doudna at the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, the Gladstone Institutes, San Francisco, and the Innovative Genomics Institute at the University of California, Berkeley. Co-leading the team was Melanie Ott, Gladstone Institutes.

The Doudna and Ott teams have developed an exciting new tool to study variants of the coronavirus. It’s a lab construct called a virus-like particle (VLP). These specially made VLPs have all the structural proteins of SARS-CoV-2 (shown above), but they contain no genetic material. Consequently, they are non-infectious replicas of the real virus that can be studied safely in any lab. Scientists don’t have to reserve time in labs equipped with heightened levels of biosafety, as is required when working with whole virus.

The VLPs also allow researchers to explore changes found in the coronavirus’s other essential proteins, not just the spike protein on its surface. In fact, all of the SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern, as defined by the World Health Organization (WHO), carry at least one mutation within the same stretch of seven amino acids in a viral protein known as the nucleocapsid (N protein). This protein, which hasn’t been widely studied, is required for the virus to make more of itself. It is also involved in the virus’s ability to package and release infectious RNA.

In the Science paper, Doudna and colleagues took a closer look at the N protein. They did so by developing a special system that used VLPs to package and deliver viral RNA messages into human cells.

Here’s how it works: The VLPs include all four of SARS-CoV-2’s structural proteins, including the spike and N proteins. In addition, they contain the RNA sequence that allows the virus to recognize its genetic material within the cell, so that it can be packaged into the next generation of viral particles.

Though the particles look just like SARS-CoV-2 from the outside, they lack the vast majority of the viral genome on the inside. But they do have one other key component: a snippet of RNA that makes cells invaded by VLPs glow. In fact, the more RNA messages a VLP delivers, the brighter the cells will glow. It allowed the researchers to spot successful invasions, while also quantifying the amount of RNA a particular VLP packed into a cell.

The researchers then produced SARS-CoV-2 VLPs including four mutations that are universally found within the N proteins of more transmissible variants of concern. That’s when they discovered those variants produced and delivered 10 times more RNA messages into cells.

The increased RNA also fits with what has been observed in people infected with the Delta variant. They produce about 10 times more virus in their nose and throat compared to people infected with the older variants.

But did those findings match what happens in the real virus? To find out, the researchers and their colleagues tested the N protein mutation found in the Delta variant in a high-level biosafety lab. And, indeed, their studies showed that the mutated virus within infected human lung cells produced about 50 times more infectious virus compared to the original SARS-CoV-2 variant.

The findings suggest that the N protein could be an important new target for effective COVID-19 therapeutics, and that tracking newly emerging mutations in the N protein might also be important for identifying new viral variants of concern. This new system is a powerful tool, and one that can also be used for exploring how newly arising variants in the future might affect the course of this terrible pandemic.

Reference:

[1] Rapid assessment of SARS-CoV-2 evolved variants using virus-like particles. Syed AM, Taha TY, Tabata T, Chen IP, Ciling A, Khalid MM, Sreekumar B, Chen PY, Hayashi JM, Soczek KM, Ott M, Doudna JA. Science. 2021 Nov 4:eabl6184.

Links:

COVID-19 Research (NIH)

NIH Support: National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases

mRNA Vaccines May Pack More Persistent Punch Against COVID-19 Than Thought

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Many people, including me, have experienced a sense of gratitude and relief after receiving the new COVID-19 mRNA vaccines. But all of us are also wondering how long the vaccines will remain protective against SARS-CoV-2, the coronavirus responsible for COVID-19.

Earlier this year, clinical trials of the Moderna and Pfizer-BioNTech vaccines indicated that both immunizations appeared to protect for at least six months. Now, a study in the journal Nature provides some hopeful news that these mRNA vaccines may be protective even longer [1].

In the new study, researchers monitored key immune cells in the lymph nodes of a group of people who received both doses of the Pfizer-BioNTech mRNA vaccine. The work consistently found hallmarks of a strong, persistent immune response against SARS-CoV-2 that could be protective for years to come.

Though more research is needed, the findings add evidence that people who received mRNA COVID-19 vaccines may not need an additional “booster” shot for quite some time, unless SARS-CoV-2 evolves into new forms, or variants, that can evade this vaccine-induced immunity. That’s why it remains so critical that more Americans get vaccinated not only to protect themselves and their loved ones, but to help stop the virus’s spread in their communities and thereby reduce its ability to mutate.

The new study was conducted by an NIH-supported research team led by Jackson Turner, Jane O’Halloran, Rachel Presti, and Ali Ellebedy at Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis. That work builds upon the group’s previous findings that people who survived COVID-19 had immune cells residing in their bone marrow for at least eight months after the infection that could recognize SARS-CoV-2 [2]. The researchers wanted to see if similar, persistent immunity existed in people who hadn’t come down with COVID-19 but who were immunized with an mRNA vaccine.

To find out, Ellebedy and team recruited 14 healthy adults who were scheduled to receive both doses of the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine. Three weeks after their first dose of vaccine, the volunteers underwent a lymph node biopsy, primarily from nodes in the armpit. Similar biopsies were repeated at four, five, seven, and 15 weeks after the first vaccine dose.

The lymph nodes are where the human immune system establishes so-called germinal centers, which function as “training camps” that teach immature immune cells to recognize new disease threats and attack them with acquired efficiency. In this case, the “threat” is the spike protein of SARS-COV-2 encoded by the vaccine.

By the 15-week mark, all of the participants sampled continued to have active germinal centers in their lymph nodes. These centers produced an army of cells trained to remember the spike protein, along with other types of cells, including antibody-producing plasmablasts, that were locked and loaded to neutralize this key protein. In fact, Ellebedy noted that even after the study ended at 15 weeks, he and his team continued to find no signs of germinal center activity slowing down in the lymph nodes of the vaccinated volunteers.

Ellebedy said the immune response observed in his team’s study appears so robust and persistent that he thinks that it could last for years. The researcher based his assessment on the fact that germinal center reactions that persist for several months or longer usually indicate an extremely vigorous immune response that culminates in the production of large numbers of long-lasting immune cells, called memory B cells. Some memory B cells can survive for years or even decades, which gives them the capacity to respond multiple times to the same infectious agent.

This study raises some really important issues for which we still don’t have complete answers: What is the most reliable correlate of immunity from COVID-19 vaccines? Are circulating spike protein antibodies (the easiest to measure) the best indicator? Do we need to know what’s happening in the lymph nodes? What about the T cells that are responsible for cell-mediated immunity?

If you follow the news, you may have seen a bit of a dust-up in the last week on this topic. Pfizer announced the need for a booster shot has become more apparent, based on serum antibodies. Meanwhile, the Food and Drug Administration and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention said such a conclusion would be premature, since vaccine protection looks really good right now, including for the delta variant that has all of us concerned.

We’ve still got a lot more to learn about the immunity generated by the mRNA vaccines. But this study—one of the first in humans to provide direct evidence of germinal center activity after mRNA vaccination—is a good place to continue the discussion.

References:

[1] SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccines induce persistent human germinal centre responses. Turner JS, O’Halloran JA, Kalaidina E, Kim W, Schmitz AJ, Zhou JQ, Lei T, Thapa M, Chen RE, Case JB, Amanat F, Rauseo AM, Haile A, Xie X, Klebert MK, Suessen T, Middleton WD, Shi PY, Krammer F, Teefey SA, Diamond MS, Presti RM, Ellebedy AH. Nature. 2021 Jun 28. [Online ahead of print]

[2] SARS-CoV-2 infection induces long-lived bone marrow plasma cells in humans. Turner JS, Kim W, Kalaidina E, Goss CW, Rauseo AM, Schmitz AJ, Hansen L, Haile A, Klebert MK, Pusic I, O’Halloran JA, Presti RM, Ellebedy AH. Nature. 2021 May 24. [Online ahead of print]

Links:

COVID-19 Research (NIH)

Ellebedy Lab (Washington University, St. Louis)

NIH Support: National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases; National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences

How Immunity Generated from COVID-19 Vaccines Differs from an Infection

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

A key issue as we move closer to ending the pandemic is determining more precisely how long people exposed to SARS-CoV-2, the COVID-19 virus, will make neutralizing antibodies against this dangerous coronavirus. Finding the answer is also potentially complicated with new SARS-CoV-2 “variants of concern” appearing around the world that could find ways to evade acquired immunity, increasing the chances of new outbreaks.

Now, a new NIH-supported study shows that the answer to this question will vary based on how an individual’s antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 were generated: over the course of a naturally acquired infection or from a COVID-19 vaccine. The new evidence shows that protective antibodies generated in response to an mRNA vaccine will target a broader range of SARS-CoV-2 variants carrying “single letter” changes in a key portion of their spike protein compared to antibodies acquired from an infection.

These results add to evidence that people with acquired immunity may have differing levels of protection to emerging SARS-CoV-2 variants. More importantly, the data provide further documentation that those who’ve had and recovered from a COVID-19 infection still stand to benefit from getting vaccinated.

These latest findings come from Jesse Bloom, Allison Greaney, and their team at Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle. In an earlier study, this same team focused on the receptor binding domain (RBD), a key region of the spike protein that studs SARS-CoV-2’s outer surface. This RBD is especially important because the virus uses this part of its spike protein to anchor to another protein called ACE2 on human cells before infecting them. That makes RBD a prime target for both naturally acquired antibodies and those generated by vaccines. Using a method called deep mutational scanning, the Seattle group’s previous study mapped out all possible mutations in the RBD that would change the ability of the virus to bind ACE2 and/or for RBD-directed antibodies to strike their targets.

In their new study, published in the journal Science Translational Medicine, Bloom, Greaney, and colleagues looked again to the thousands of possible RBD variants to understand how antibodies might be expected to hit their targets there [1]. This time, they wanted to explore any differences between RBD-directed antibodies based on how they were acquired.

Again, they turned to deep mutational scanning. First, they created libraries of all 3,800 possible RBD single amino acid mutants and exposed the libraries to samples taken from vaccinated individuals and unvaccinated individuals who’d been previously infected. All vaccinated individuals had received two doses of the Moderna mRNA vaccine. This vaccine works by prompting a person’s cells to produce the spike protein, thereby launching an immune response and the production of antibodies.

By closely examining the results, the researchers uncovered important differences between acquired immunity in people who’d been vaccinated and unvaccinated people who’d been previously infected with SARS-CoV-2. Specifically, antibodies elicited by the mRNA vaccine were more focused to the RBD compared to antibodies elicited by an infection, which more often targeted other portions of the spike protein. Importantly, the vaccine-elicited antibodies targeted a broader range of places on the RBD than those elicited by natural infection.

These findings suggest that natural immunity and vaccine-generated immunity to SARS-CoV-2 will differ in how they recognize new viral variants. What’s more, antibodies acquired with the help of a vaccine may be more likely to target new SARS-CoV-2 variants potently, even when the variants carry new mutations in the RBD.

It’s not entirely clear why these differences in vaccine- and infection-elicited antibody responses exist. In both cases, RBD-directed antibodies are acquired from the immune system’s recognition and response to viral spike proteins. The Seattle team suggests these differences may arise because the vaccine presents the viral protein in slightly different conformations.

Also, it’s possible that mRNA delivery may change the way antigens are presented to the immune system, leading to differences in the antibodies that get produced. A third difference is that natural infection only exposes the body to the virus in the respiratory tract (unless the illness is very severe), while the vaccine is delivered to muscle, where the immune system may have an even better chance of seeing it and responding vigorously.

Whatever the underlying reasons turn out to be, it’s important to consider that humans are routinely infected and re-infected with other common coronaviruses, which are responsible for the common cold. It’s not at all unusual to catch a cold from seasonal coronaviruses year after year. That’s at least in part because those viruses tend to evolve to escape acquired immunity, much as SARS-CoV-2 is now in the process of doing.

The good news so far is that, unlike the situation for the common cold, we have now developed multiple COVID-19 vaccines. The evidence continues to suggest that acquired immunity from vaccines still offers substantial protection against the new variants now circulating around the globe.

The hope is that acquired immunity from the vaccines will indeed produce long-lasting protection against SARS-CoV-2 and bring an end to the pandemic. These new findings point encouragingly in that direction. They also serve as an important reminder to roll up your sleeve for the vaccine if you haven’t already done so, whether or not you’ve had COVID-19. Our best hope of winning this contest with the virus is to get as many people immunized now as possible. That will save lives, and reduce the likelihood of even more variants appearing that might evade protection from the current vaccines.

Reference:

[1] Antibodies elicited by mRNA-1273 vaccination bind more broadly to the receptor binding domain than do those from SARS-CoV-2 infection. Greaney AJ, Loes AN, Gentles LE, Crawford KHD, Starr TN, Malone KD, Chu HY, Bloom JD. Sci Transl Med. 2021 Jun 8.

Links:

COVID-19 Research (NIH)

Bloom Lab (Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle)

NIH Support: National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases

Human Antibodies Target Many Parts of Coronavirus Spike Protein

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

For many people who’ve had COVID-19, the infections were thankfully mild and relatively brief. But these individuals’ immune systems still hold onto enduring clues about how best to neutralize SARS-CoV-2, the coronavirus that causes COVID-19. Discovering these clues could point the way for researchers to design highly targeted treatments that could help to save the lives of folks with more severe infections.

An NIH-funded study, published recently in the journal Science, offers the most-detailed picture yet of the array of antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 found in people who’ve fully recovered from mild cases of COVID-19. This picture suggests that an effective neutralizing immune response targets a wider swath of the virus’ now-infamous spike protein than previously recognized.

To date, most studies of natural antibodies that block SARS-CoV-2 have zeroed in on those that target a specific portion of the spike protein known as the receptor-binding domain (RBD)—and with good reason. The RBD is the portion of the spike that attaches directly to human cells. As a result, antibodies specifically targeting the RBD were an excellent place to begin the search for antibodies capable of fending off SARS-CoV-2.

The new study, led by Gregory Ippolito and Jason Lavinder, The University of Texas at Austin, took a different approach. Rather than narrowing the search, Ippolito, Lavinder, and colleagues analyzed the complete repertoire of antibodies against the spike protein from four people soon after their recoveries from mild COVID-19.

What the researchers found was a bit of a surprise: the vast majority of antibodies—about 84 percent—targeted other portions of the spike protein than the RBD. This suggests a successful immune response doesn’t concentrate on the RBD. It involves production of antibodies capable of covering areas across the entire spike.

The researchers liken the spike protein to an umbrella, with the RBD at the tip of the “canopy.” While some antibodies do bind RBD at the tip, many others apparently target the protein’s canopy, known as the N-terminal domain (NTD).

Further study in cell culture showed that NTD-directed antibodies do indeed neutralize the virus. They also prevented a lethal mouse-adapted version of the coronavirus from infecting mice.

One reason these findings are particularly noteworthy is that the NTD is one part of the viral spike protein that has mutated frequently, especially in several emerging variants of concern, including the B.1.1.7 “U.K. variant” and the B.1.351 “South African variant.” It suggests that one reason these variants are so effective at evading our immune systems to cause breakthrough infections, or re-infections, is that they’ve mutated their way around some of the human antibodies that had been most successful in combating the original coronavirus variant.

Also noteworthy, about 40 percent of the circulating antibodies target yet another portion of the spike called the S2 subunit. This finding is especially encouraging because this portion of SARS-CoV-2 does not seem as mutable as the NTD segment, suggesting that S2-directed antibodies might offer a layer of protection against a wider array of variants. What’s more, the S2 subunit may make an ideal target for a possible pan-coronavirus vaccine since this portion of the spike is widely conserved in SARS-CoV-2 and related coronaviruses.

Taken together, these findings will prove useful for designing COVID-19 vaccine booster shots or future vaccines tailored to combat SARS-COV-2 variants of concern. The findings also drive home the conclusion that the more we learn about SARS-CoV-2 and the immune system’s response to neutralize it, the better position we all will be in to thwart this novel coronavirus and any others that might emerge in the future.

Reference:

[1] Prevalent, protective, and convergent IgG recognition of SARS-CoV-2 non-RBD spike epitopes. Voss WN, Hou YJ, Johnson NV, Delidakis G, Kim JE, Javanmardi K, Horton AP, Bartzoka F, Paresi CJ, Tanno Y, Chou CW, Abbasi SA, Pickens W, George K, Boutz DR, Towers DM, McDaniel JR, Billick D, Goike J, Rowe L, Batra D, Pohl J, Lee J, Gangappa S, Sambhara S, Gadush M, Wang N, Person MD, Iverson BL, Gollihar JD, Dye J, Herbert A, Finkelstein IJ, Baric RS, McLellan JS, Georgiou G, Lavinder JJ, Ippolito GC. Science. 2021 May 4:eabg5268.

Links:

COVID-19 Research (NIH)

Gregory Ippolito (University of Texas at Austin)

NIH Support: National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases; National Cancer Institute; National Institute of General Medical Sciences; National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences

Next Page