mutations

Latest on Omicron Variant and COVID-19 Vaccine Protection

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

There’s been great concern about the new Omicron variant of SARS-CoV-2, the coronavirus that causes COVID-19. A major reason is Omicron has accumulated over 50 mutations, including about 30 in the spike protein, the part of the coronavirus that mRNA vaccines teach our immune systems to attack. All of these genetic changes raise the possibility that Omicron could cause breakthrough infections in people who’ve already received a Pfizer or Moderna mRNA vaccine.

So, what does the science show? The first data to emerge present somewhat encouraging results. While our existing mRNA vaccines still offer some protection against Omicron, there appears to be a significant decline in neutralizing antibodies against this variant in people who have received two shots of an mRNA vaccine.

However, initial results of studies conducted both in the lab and in the real world show that people who get a booster shot, or third dose of vaccine, may be better protected. Though these data are preliminary, they suggest that getting a booster will help protect people already vaccinated from breakthrough or possible severe infections with Omicron during the winter months.

Though Omicron was discovered in South Africa only last month, researchers have been working around the clock to learn more about this variant. Last week brought the first wave of scientific data on Omicron, including interesting work from a research team led by Alex Sigal, Africa Health Research Institute, Durban, South Africa [1].

In lab studies working with live Omicron virus, the researchers showed that this variant still relies on the ACE2 receptor to infect human lung cells. That’s really good news. It means that the therapeutic tools already developed, including vaccines, should generally remain useful for combatting this new variant.

Sigal and colleagues also tested the ability of antibodies in the plasma from 12 fully vaccinated individuals to neutralize Omicron. Six of the individuals had no history of COVID-19. The other six had been infected with the original variant in the first wave of infections in South Africa.

As expected, the samples showed very strong neutralization against the original SARS-CoV-2 variant. However, antibodies from people who’d been previously vaccinated with the two-dose Pfizer vaccine took a significant hit against Omicron, showing about a 40-fold decline in neutralizing ability.

This escape from immunity wasn’t complete. Indeed, blood samples from five individuals showed relatively good antibody levels against Omicron. All five had previously been infected with SARS-CoV-2 in addition to being vaccinated. These findings add to evidence on the value of full vaccination for protecting against reinfections in people who’ve had COVID-19 previously.

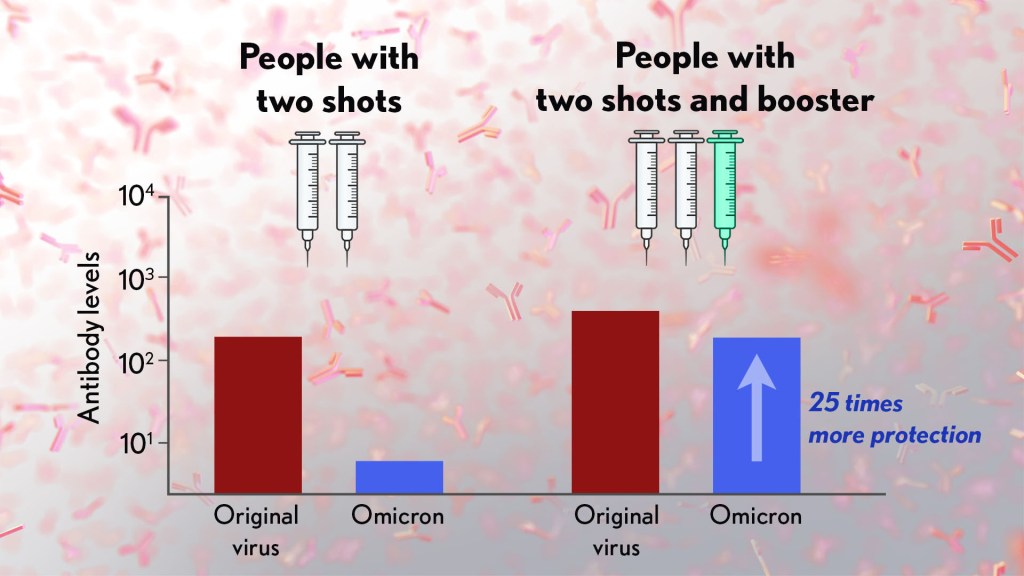

Also of great interest were the first results of the Pfizer study, which the company made available in a news release [2]. Pfizer researchers also conducted laboratory studies to test the neutralizing ability of blood samples from 19 individuals one month after a second shot compared to 20 others one month after a booster shot.

These studies showed that the neutralizing ability of samples from those who’d received two shots had a more than 25-fold decline relative to the original virus. Together with the South Africa data, it suggests that the two-dose series may not be enough to protect against breakthrough infections with the Omicron variant.

In much more encouraging news, their studies went on to show that a booster dose of the Pfizer vaccine raised antibody levels against Omicron to a level comparable to the two-dose regimen against the original variant (as shown in the figure above). While efforts already are underway to develop an Omicron-specific COVID-19 vaccine, these findings suggest that it’s already possible to get good protection against this new variant by getting a booster shot.

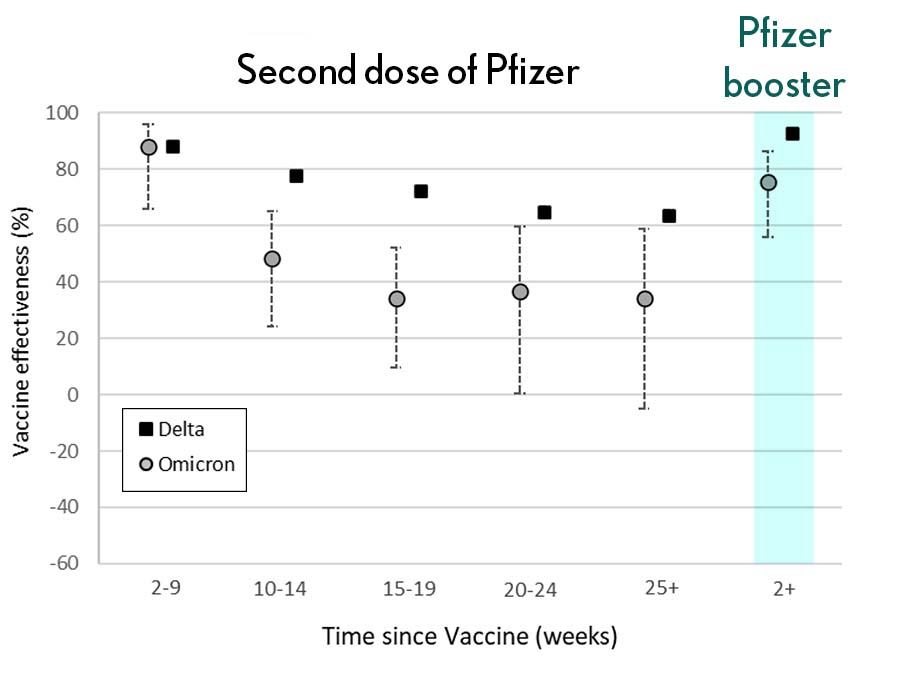

Very recently, real-world data from the United Kingdom, where Omicron cases are rising rapidly, are providing additional evidence for how boosters can help. In a preprint [3], Andrews et. al showed the effectiveness of two shots of Pfizer mRNA vaccine trended down after four months to about 40 percent. That’s not great, but note that 40 percent is far better than zero. So, clearly there is some protection provided.

Most impressively (as shown in the figure from Andrews N, et al.) a booster substantially raised that vaccine effectiveness to about 80 percent. That’s not quite as high as for Delta, but certainly an encouraging result. Once again, these data show that boosting the immune system after a pause produces enhanced immunity against new viral variants, even though the booster was designed from the original virus. Your immune system is awfully clever. You get both quantitative and qualitative benefits.

It’s also worth noting that the Omicron variant mostly doesn’t have mutations in portions of its genome that are the targets of other aspects of vaccine-induced immunity, including T cells. These cells are part of the body’s second line of defense and are generally harder for viruses to escape. While T cells can’t prevent infection, they help protect against more severe illness and death.

It’s important to note that scientists around the world are also closely monitoring Omicron’s severity While this variant appears to be highly transmissible, and it is still early for rigorous conclusions, the initial research indicates this variant may actually produce milder illness than Delta, which is currently the dominant strain in the United States.

But there’s still a tremendous amount of research to be done that could change how we view Omicron. This research will take time and patience.

What won’t change, though, is that vaccines are the best way to protect yourself and others against COVID-19. (And these recent data provide an even-stronger reason to get a booster now if you are eligible.) Wearing a mask, especially in public indoor settings, offers good protection against the spread of all SARS-CoV-2 variants. If you’ve got symptoms or think you may have been exposed, get tested and stay home if you get a positive result. As we await more answers, it’s as important as ever to use all the tools available to keep yourself, your loved ones, and your community happy and healthy this holiday season.

References:

[1] SARS-CoV-2 Omicron has extensive but incomplete escape of Pfizer BNT162b2 elicited neutralization and requires ACE2 for infection. Sandile C, et al. Sandile C, et al. medRxiv preprint. December 9, 2021.

[2] Pfizer and BioNTech provide update on Omicron variant. Pfizer. December 8, 2021.

[3] Effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines against the Omicron (B.1.1.529) variant of concern. Andrews N, et al. KHub.net preprint. December 10, 2021.

Links:

COVID-19 Research (NIH)

Sigal Lab (Africa Health Research Institute, Durban, South Africa)

New Technology Opens Evolutionary Window into Brain Development

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

One of the great mysteries in biology is how we humans ended up with such large, complex brains. In search of clues, researchers have spent years studying the protein-coding genes activated during neurodevelopment. But some answers may also be hiding in non-coding regions of the human genome, where sequences called regulatory elements increase or decrease the activity of genes.

A fascinating example involves a type of regulatory element called a human accelerated region (HAR). Although “human” is part of this element’s name, it turns out that the genomes of all vertebrates—not just humans—contain the DNA segments now designated as HARs.

In most organisms, HARs show a relatively low rate of mutation, which means these regulatory elements have been highly conserved across species throughout evolutionary time [1]. The big exception is Homo sapiens, in which HARs have exhibited a much higher rate of mutations.

The accelerated rate of HARs mutations observed in humans suggest that, over the course of very long periods of time, these genomic changes might have provided our species with some sort of evolutionary advantage. What might that be? Many have speculated the advantage might involve the brain because HARs are often associated with genes involved in neurodevelopment. Now, in a paper published in the journal Neuron, an NIH-supported team confirms that’s indeed the case [2].

In the new work, researchers found that about half of the HARs in the human genome influence the activity, or expression, of protein-coding genes in neural cells and tissues during the brain’s development [3]. The researchers say their study—the most comprehensive to date of the 3,171 HARs in the human genome—firmly establishes that this type of regulatory element helps to drive patterns of neurodevelopmental gene activity specific to humans.

Yet to be determined is precisely how HARs affect the development of the human brain. The quest to uncover these details will no doubt shed new light on fundamental questions about the brain, its billions of neurons, and their trillions of interconnections. For example, why does human neural development span decades, longer than the life spans of most primates and other mammals? Answering such questions could also reveal new clues into a range of cognitive and behavioral disorders. In fact, early research has already made tentative links between HARs and neurodevelopmental conditions such as autism spectrum disorder and schizophrenia [3].

The latest work was led by Kelly Girskis, Andrew Stergachis, and Ellen DeGennaro, all of whom were in the lab of Christopher Walsh while working on the project. An NIH grantee, Walsh is director of the Allen Discovery Center for Brain Evolution at Boston Children’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, which is supported by the Paul G. Allen Foundation Frontiers Group, and is an Investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Though HARs have been studied since 2006, one of the big challenges in systematically assessing them has been technological. The average length of a HAR is about 269 bases of DNA, but current technologies for assessing function can only easily analyze DNA molecules that span 150 bases or less.

Ryan Doan, who was then in the Walsh Lab, and his colleagues solved the problem by creating a new machine called CaptureMPRA. (MPRA is short for “massively parallel reporter assays.”) This technological advance cleverly barcodes HARs and, more importantly, makes it possible to analyze HARs up to about 500 bases in length.

Using CaptureMPRA technology in tandem with cell culture studies, researchers rolled up their sleeves and conducted comprehensive, full-sequence analyses of more than 3,000 HARs. In their initial studies, primarily in neural cells, they found nearly half of human HARs are active to drive gene expression in cell culture. Of those, 42 percent proved to have increased ability to enhance gene expression compared to their orthologues, or counterparts, in chimpanzees.

Next, the team integrated these data with an existing epigenetic dataset derived from developing human brain cells, as well as additional datasets generated from sorted brain cell types. They found that many HARs appeared to have the ability to increase the activity of protein-coding genes, while a smaller—but very significant—subset of the HARs appeared to be enhancing gene expression specifically in neural progenitor cells, which are responsible for making various neural cell types.

The data suggest that as the human HAR sequences mutated and diverged from other mammals, they increased their ability to enhance or sometimes suppress the activity of certain genes in neural cells. To illustrate this point, the researchers focused on two HARs that appear to interact specifically with a gene referred to as R17. This gene can have highly variable gene expression patterns not only in different human cell types, but also in cells from other vertebrates and non-vertebrates.

In the human cerebral cortex, the outermost part of the brain that’s responsible for complex behaviors, R17 is expressed only in neural progenitor cells and only at specific time points. The researchers found that R17 slows the progression of neural progenitor cells through the cell cycle. That might seem strange, given the billions of neurons that need to be made in the cortex. But it’s consistent with the biology. In the human, it takes more than 130 days for the cortex to complete development, compared to about seven days in the mouse.

Clearly, to learn more about how the human brain evolved, researchers will need to look for clues in many parts of the genome at once, including its non-coding regions. To help researchers navigate this challenging terrain, the Walsh team has created an online resource displaying their comprehensive HAR data. It will appear soon, under the name HAR Hub, on the University of California Santa Cruz Genome Browser.

References:

[1] An RNA gene expressed during cortical development evolved rapidly in humans. Pollard KS, Salama SR, Lambert N, Lambot MA, Coppens S, Pedersen JS, Katzman S, King B, Onodera C, Siepel A, Kern AD, Dehay C, Igel H, Ares M Jr, Vanderhaeghen P, Haussler D. Nature. 2006 Sep 14;443(7108):167-72.

[2] Rewiring of human neurodevelopmental gene regulatory programs by human accelerated regions. Girskis KM, Stergachis AB, DeGennaro EM, Doan RN, Qian X, Johnson MB, Wang PP, Sejourne GM, Nagy MA, Pollina EA, Sousa AMM, Shin T, Kenny CJ, Scotellaro JL, Debo BM, Gonzalez DM, Rento LM, Yeh RC, Song JHT, Beaudin M, Fan J, Kharchenko PV, Sestan N, Greenberg ME, Walsh CA. Neuron. 2021 Aug 25:S0896-6273(21)00580-8.

[3] Mutations in human accelerated regions disrupt cognition and social behavior. Doan RN, Bae BI, Cubelos B, Chang C, Hossain AA, Al-Saad S, Mukaddes NM, Oner O, Al-Saffar M, Balkhy S, Gascon GG; Homozygosity Mapping Consortium for Autism, Nieto M, Walsh CA. Cell. 2016 Oct 6;167(2):341-354.

Links:

Christopher Walsh Laboratory (Boston Children’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School)

The Paul G. Allen Foundation Frontiers Group (Seattle)

NIH Support: National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke; National Institute of Mental Health; National Institute of General Medical Sciences; National Cancer Institute

Infections with ‘U.K. Variant’ B.1.1.7 Have Greater Risk of Mortality

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

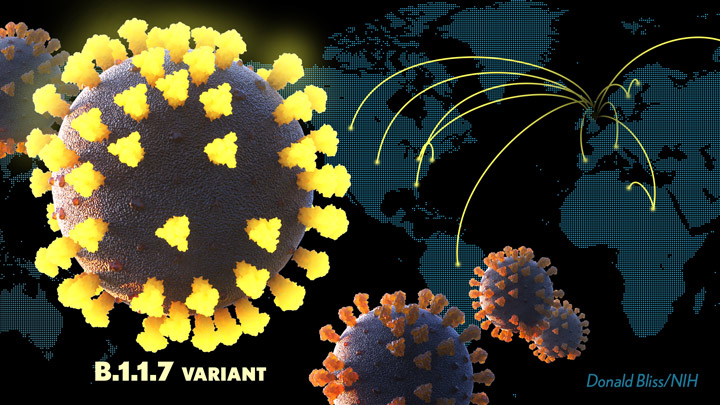

Since the genome sequence of SARS-CoV-2, the virus responsible for COVID-19, was first reported in January 2020, thousands of variants have been reported. In the vast majority of cases, these variants, which arise from random genomic changes as SARS-CoV-2 makes copies of itself in an infected person, haven’t raised any alarm among public health officials. But that’s now changed with the emergence of at least three variants carrying mutations that potentially make them even more dangerous.

At the top of this short list is a variant known as B.1.1.7, first detected in the United Kingdom in September 2020. This variant is considerably more contagious than the original virus. It has spread rapidly around the globe and likely accounts already for at least one-third of all cases in the United States [1]. Now comes more troubling news: emerging evidence indicates that infection with this B.1.1.7 variant also comes with an increased risk of severe illness and death [2].

The findings, reported in Nature, come from Nicholas Davies, Karla Diaz-Ordaz, and Ruth Keogh, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. The London team earlier showed that this new variant is 43 to 90 percent more transmissible than pre-existing variants that had been circulating in England [3]. But in the latest paper, the researchers followed up on conflicting reports about the virulence of B.1.1.7.

They did so with a large British dataset linking more than 2.2 million positive SARS-CoV-2 tests to 17,452 COVID-19 deaths from September 1, 2020, to February 14, 2021. In about half of the cases (accounting for nearly 5,000 deaths), it was possible to discern whether or not the infection had been caused by the B.1.1.7 variant.

Based on this evidence, the researchers calculated the risk of death associated with B.1.1.7 infection. Their estimates suggest that B.1.1.7 infection was associated with 55 percent greater mortality compared to other SARS-CoV-2 variants over this time period.

For a 55- to 69-year-old male, this translates to a 0.9-percent absolute, or personal, risk of death, up from 0.6 percent for the older variants. That means nine in every 1,000 people in this age group who test positive with the B.1.1.7 variant would be expected to die from COVID-19 a month later. For those infected with the original virus, that number would be six.

These findings are in keeping with those of another recent study reported in the British Medical Journal [4]. In that case, researchers at the University of Exeter and the University of Bristol found that the B.1.1.7 variant was associated with a 64 percent greater chance of dying compared to earlier variants. That’s based on an analysis of data from more than 100,000 COVID-19 patients in the U.K. from October 1, 2020, to January 28, 2021.

That this variant comes with increased disease severity and mortality is particularly troubling news, given the highly contagious nature of B.1.1.7. In fact, Davies’ team has concluded that the emergence of new SARS-CoV-2 variants now threaten to slow or even cancel out improvements in COVID-19 treatment that have been made over the last year. These variants include not only B1.1.7, but also B.1.351 originating in South Africa and P.1 from Brazil.

The findings are yet another reminder that, while we’re making truly remarkable progress in the fight against COVID-19 with increasing availability of safe and effective vaccines (more than 45 million Americans are now fully immunized), now is not the time to get complacent. This devastating pandemic isn’t over yet.

The best way to continue the fight against all SARS-CoV-2 variants is for each one of us to do absolutely everything we can to stop their spread. This means that taking the opportunity to get vaccinated as soon as it is offered to you, and continuing to practice those public health measures we summarize as the three Ws: Wear a mask, Watch your distance, Wash your hands often.

References:

[1] US COVID-19 Cases Caused by Variants. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

[2] Increased mortality in community-tested cases of SARS-CoV-2 lineage B.1.1.7. Davies NG, Jarvis CI; CMMID COVID-19 Working Group, Edmunds WJ, Jewell NP, Diaz-Ordaz K, Keogh RH. Nature. 2021 Mar 15.

[3] Estimated transmissibility and impact of SARS-CoV-2 lineage B.1.1.7 in England. Davies NG, Abbott S, Barnard RC, Jarvis CI, Kucharski AJ, Munday JD, Pearson CAB, Russell TW, Tully DC, Washburne AD, Wenseleers T, Gimma A, Waites W, Wong KLM, van Zandvoort K, Silverman JD; CMMID COVID-19 Working Group; COVID-19 Genomics UK (COG-UK) Consortium, Diaz-Ordaz K, Keogh R, Eggo RM, Funk S, Jit M, Atkins KE, Edmunds WJ.

Science. 2021 Mar 3:eabg3055.

[4] Risk of mortality in patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 variant of concern 202012/1: matched cohort study. Challen R, Brooks-Pollock E, Read JM, Dyson L, Tsaneva-Atanasova K, Danon L. BMJ. 2021 Mar 9;372:n579.

Links:

COVID-19 Research (NIH)

Nicholas Davies (London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, U.K.)

Ruth Keogh (London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, U.K.)

Mapping Which Coronavirus Variants Will Resist Antibody Treatments

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

You may have heard about the new variants of SARS-CoV-2—the coronavirus that causes COVID-19—that have appeared in other parts of the world and have now been detected in the United States. These variants, particularly one called B.1.351 that was first identified in South Africa, have raised growing concerns about the extent to which their mutations might help them evade current antibody treatments and highly effective vaccines.

While researchers take a closer look, it’s already possible in the laboratory to predict which mutations will help SARS-CoV-2 evade our therapies and vaccines, and even to prepare for the emergence of new mutations before they occur. In fact, an NIH-funded study, which originally appeared as a bioRxiv pre-print in November and was recently peer-reviewed and published in Science, has done exactly that. In the study, researchers mapped all possible mutations that would allow SARS-CoV-2 to resist treatment with three different monoclonal antibodies developed for treatment of COVID-19 [1].

The work, led by Jesse Bloom, Allison Greaney, and Tyler Starr, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center, Seattle, focused on the receptor binding domain (RBD), a key region of the spike protein that studs SARS-CoV-2’s outer surface. The virus uses RBD to anchor itself to the ACE2 receptor of human cells before infecting them. That makes the RBD a prime target for the antibodies that our bodies generate to defend against the virus.

In the new study, researchers used a method called deep mutational scanning to find out which mutations positively or negatively influence the RBD from being able to bind to ACE2 and/or thwart antibodies from striking their target. Here’s how it works: Rather than waiting for new mutations to arise, the researchers created a library of RBD fragments, each of which contained a change in a single nucleotide “letter” that would alter the spike protein’s shape and/or function by swapping one amino acid for another. It turns out that there are more than 3,800 such possible mutations, and Bloom’s team managed to make all but a handful of those versions of the RBD fragment.

The team then used a standard laboratory approach to measure systematically how each of those single-letter typos altered RBD’s ability to bind ACE2 and infect human cells. They also measured how those changes affected three different therapeutic antibodies from recognizing and binding to the viral RBD. Those antibodies include two developed by Regeneron (REGN10933 and REGN10987), which have been granted emergency use authorization for treatment of COVID-19 together as a cocktail called REGN-COV2. They also looked at an antibody developed by Eli Lilly (LY-CoV016), which is now in phase 3 clinical trials for treating COVID-19.

Based on the data, the researchers created four mutational maps for SARS-CoV-2 to escape each of the three therapeutic antibodies, as well as for the REGN-COV2 cocktail. Their studies show most of the mutations that would allow SARS-CoV-2 to escape treatment differed between the two Regeneron antibodies. That’s encouraging because it indicates that the virus likely needs more than one mutation to become resistant to the REGN-COV2 cocktail. However, it appears there’s one spot where a single mutation could allow the virus to resist REGN-COV2 treatment.

The escape map for LY-CoV016 similarly showed a number of mutations that could allow the virus to escape. Importantly, while some of those changes might impair the virus’s ability to cause infection, most of them appeared to come at little to no cost to the virus to reproduce.

How do these laboratory data relate to the real world? To begin to explore this question, the researchers teamed up with Jonathan Li, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston. They looked at an immunocompromised patient who’d had COVID-19 for an unusually long time and who was treated with the Regeneron cocktail for 145 days, giving the virus time to replicate and acquire new mutations.

Viral genome data from the infected patient showed that these maps can indeed be used to predict likely paths of viral evolution. Over the course of the antibody treatment, SARS-CoV-2 showed changes in the frequency of five mutations that would change the makeup of the spike protein and its RBD. Based on the newly drawn escape maps, three of those five are expected to reduce the efficacy of REGN10933. One of the others is expected to limit binding by the other antibody, REGN10987.

The researchers also looked to data from all known circulating SARS-CoV-2 variants as of Jan. 11, 2021, for evidence of escape mutations. They found that a substantial number of mutations with potential to allow escape from antibody treatment already are present, particularly in parts of Europe and South Africa.

However, it’s important to note that these maps reflect just three important antibody treatments. Bloom says they’ll continue to produce maps for other promising therapeutic antibodies. They’ll also continue to explore where changes in the virus could allow for escape from the more diverse set of antibodies produced by our immune system after a COVID-19 infection or vaccination.

While it’s possible some COVID-19 vaccines may offer less protection against some of these new variants—and recent results have suggested the AstraZeneca vaccine may not provide much protection against the South African variant, there’s still enough protection in most other current vaccines to prevent serious illness, hospitalization, and death. And the best way to keep SARS-CoV-2 from finding new ways to escape our ongoing efforts to end this terrible pandemic is to double down on whatever we can do to prevent the virus from multiplying and spreading in the first place.

For now, emergence of these new variants should encourage all of us to take steps to slow the spread of SARS-CoV-2. That means following the three W’s: Wear a mask, Watch your distance, Wash your hands often. It also means rolling up our sleeves to get vaccinated as soon as the opportunity arises.

Reference:

[1] Prospective mapping of viral mutations that escape antibodies used to treat COVID-19.

Starr TN, Greaney AJ, Addetia A, Hannon WW, Choudhary MC, Dingens AS, Li JZ, Bloom JD.

Science. 2021 Jan 25:eabf9302.

Links:

COVID-19 Research (NIH)

Bloom Lab (Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center, Seattle)

NIH Support: National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases

Gene-Editing Advance Puts More Gene-Based Cures Within Reach

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

There’s been tremendous excitement recently about the potential of CRISPR and related gene-editing technologies for treating or even curing sickle cell disease (SCD), muscular dystrophy, HIV, and a wide range of other devastating conditions. Now comes word of another remarkable advance—called “prime editing”—that may bring us even closer to reaching that goal.

As groundbreaking as CRISPR/Cas9 has been for editing specific genes, the system has its limitations. The initial version is best suited for making a double-stranded break in DNA, followed by error-prone repair. The outcome is generally to knock out the target. That’s great if eliminating the target is the desired goal. But what if the goal is to fix a mutation by editing it back to the normal sequence?

The new prime editing system, which was described recently by NIH-funded researchers in the journal Nature, is revolutionary because it offers much greater control for making a wide range of precisely targeted edits to the DNA code, which consists of the four “letters” (actually chemical bases) A, C, G, and T [1].

Already, in tests involving human cells grown in the lab, the researchers have used prime editing to correct genetic mutations that cause two inherited diseases: SCD, a painful, life-threatening blood disorder, and Tay-Sachs disease, a fatal neurological disorder. What’s more, they say the versatility of their new gene-editing system means it can, in principle, correct about 89 percent of the more than 75,000 known genetic variants associated with human diseases.

In standard CRISPR, a scissor-like enzyme called Cas9 is used to cut all the way through both strands of the DNA molecule’s double helix. That usually results in the cell’s DNA repair apparatus inserting or deleting DNA letters at the site. As a result, CRISPR is extremely useful for disrupting genes and inserting or removing large DNA segments. However, it is difficult to use this system to make more subtle corrections to DNA, such as swapping a letter T for an A.

To expand the gene-editing toolbox, a research team led by David R. Liu, Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard, Cambridge, MA, previously developed a class of editing agents called base editors [2,3]. Instead of cutting DNA, base editors directly convert one DNA letter to another. However, base editing has limitations, too. It works well for correcting four of the most common single letter mutations in DNA. But at least so far, base editors haven’t been able to make eight other single letter changes, or fix extra or missing DNA letters.

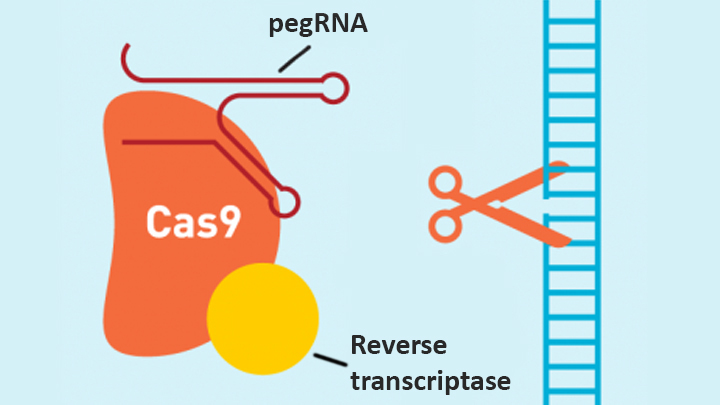

In contrast, the new prime editing system can precisely and efficiently swap any single letter of DNA for any other, and can make both deletions and insertions, at least up to a certain size. The system consists of a modified version of the Cas9 enzyme fused with another enzyme, called reverse transcriptase, and a specially engineered guide RNA, called pegRNA. The latter contains the desired gene edit and steers the needed editing apparatus to a specific site in a cell’s DNA.

Once at the site, the Cas9 nicks one strand of the double helix. Then, reverse transcriptase uses one DNA strand to “prime,” or initiate, the letter-by-letter transfer of new genetic information encoded in the pegRNA into the nicked spot, much like the search-and-replace function of word processing software. The process is then wrapped up when the prime editing system prompts the cell to remake the other DNA strand to match the new genetic information.

So far, in tests involving human cells grown in a lab dish, Liu and his colleagues have used prime editing to correct the most common mutation that causes SCD, converting a T to an A. They were also able to remove four DNA letters to correct the most common mutation underlying Tay-Sachs disease, a devastating condition that typically produces symptoms in children within the first year and leads to death by age four. The researchers also used their new system to insert new DNA segments up to 44 letters long and to remove segments at least 80 letters long.

Prime editing does have certain limitations. For example, 11 percent of known disease-causing variants result from changes in the number of gene copies, and it’s unclear if prime editing can insert or remove DNA that’s the size of full-length genes—which may contain up to 2.4 million letters.

It’s also worth noting that now-standard CRISPR editing and base editors have been tested far more thoroughly than prime editing in many different kinds of cells and animal models. These earlier editing technologies also may be more efficient for some purposes, so they will likely continue to play unique and useful roles in biomedicine.

As for prime editing, additional research is needed before we can consider launching human clinical trials. Among the areas that must be explored are this technology’s safety and efficacy in a wide range of cell types, and its potential for precisely and safely editing genes in targeted tissues within living animals and people.

Meanwhile, building on all these bold advances, efforts are already underway to accelerate the development of affordable, accessible gene-based cures for SCD and HIV on a global scale. Just last month, NIH and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation announced a collaboration that will invest at least $200 million over the next four years toward this goal. Last week, I had the chance to present this plan and discuss it with global health experts at the Grand Challenges meeting Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. The project is an unprecedented partnership designed to meet an unprecedented opportunity to address health conditions that once seemed out of reach but—as this new work helps to show—may now be within our grasp.

References:

[1] Search-and-replace genome editing without double-strand breaks or donor DNA. Anzalone AV, Randolph PB, Davis JR, Sousa AA, Koblan LW, Levy JM, Chen PJ, Wilson C, Newby GA, Raguram A, Liu DR. Nature. Online 2019 October 21. [Epub ahead of print]

[2] Programmable editing of a target base in genomic DNA without double-stranded DNA cleavage. Komor AC, Kim YB, Packer MS, Zuris JA, Liu DR. Nature. 2016 May 19;533(7603):420-424.

[3] Programmable base editing of A•T to G•C in genomic DNA without DNA cleavage. Gaudelli NM, Komor AC, Rees HA, Packer MS, Badran AH, Bryson DI, Liu DR. Nature. 2017 Nov 23;551(7681):464-471.

Links:

Tay-Sachs Disease (Genetics Home Reference/National Library of Medicine/NIH)

Sickle Cell Disease (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute/NIH)

Cure Sickle Cell Initiative (NHLBI)

What are Genome Editing and CRISPR-Cas9? (National Library of Medicine/NIH)

Somatic Cell Genome Editing Program (Common Fund/NIH)

David R. Liu (Harvard, Cambridge, MA)

NIH Support: National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases; National Human Genome Research Institute; National Institute for General Medical Sciences; National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering; National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences

Finding New Genetic Mutations Amid Healthy Cells

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

You might recall learning in biology class that the cells constantly replicating and dividing in our bodies all carry the same DNA, inherited in equal parts from each parent. But it’s become increasingly clear in recent years that even seemingly healthy tissues contain neighborhoods of cells bearing their own acquired genetic mutations. The question is: What do all those altered cells mean for our health?

With support from a 2018 NIH Director’s New Innovator Award, Po-Ru Loh, Harvard Medical School, Boston, is on a quest to find out, though without the need for sequencing lots of DNA in his own lab. Loh will instead develop ultrasensitive computational tools to pick up on those often-subtle alterations within the vast troves of genomic data already stored in databases around the world.

How is that possible? The math behind it might be complex, but the underlying idea is surprisingly simple. His algorithms look for spots in the genome where a slight imbalance exists in the quantity of DNA inherited from mom versus dad.

Actually, Loh can’t tell from the data which parent provided any snippet of chromosomal DNA. But looking at DNA sequenced from a mixture of many cells, he can infer which stretches of DNA were most likely inherited together from a single parent.

Any slight skew in those quantities point the way to genomic territory where a tiny portion of chromosomal DNA either went missing or became duplicated in some cells. This common occurrence, especially in older adults, leads to a condition called genetic mosaicism, meaning that, contrary to most biology textbooks, all cells aren’t exactly the same.

By detecting those subtle imbalances in the data, Loh can pinpoint small DNA alterations, even when they occur in 1 in 1,000 cells collected from a person’s bloodstream, saliva, or tissues. That’s the kind of sensitivity that most scientists would not have thought possible.

Loh has already begun putting his new computational approach to work, as reported in Nature last year [1]. In DNA data from blood samples of more than 150,000 participants in the United Kingdom Biobank, his method uncovered well over 8,000 mosaic chromosomal alterations.

The study showed that some of those alterations were associated with an increased risk of developing blood cancers. However, it’s important to note that most people with evidence of mosaicism won’t go on to develop cancer. The researchers also made the unexpected discovery that some individuals carried genetic variants that made them more prone than others to pick up new mutations in their blood cells.

What’s especially exciting is Loh’s computational tools now make it possible to search for signs of mosaicism within all the genetic data that’s ever been generated. Even more importantly, these tools will allow Loh and other researchers to ask and answer important questions about the consequences of mosaicism for a wide range of diseases.

Reference:

[1] Insights into clonal haematopoiesis from 8,342 mosaic chromosomal alterations. Loh PR, Genovese G, Handsaker RE, Finucane HK, Reshef YA, Palamara PF, Birmann BM, Talkowski ME, Bakhoum SF, McCarroll SA, Price AL. Nature. 2018 Jul;559(7714):350-355.

Links:

Loh Lab (Harvard Medical School, Boston)

Loh Project Information (NIH RePORTER)

NIH Director’s New Innovator Award (Common Fund)

NIH Support: Common Fund; National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences

Study Finds Genetic Mutations in Healthy Human Tissues

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

The standard view of biology is that every normal cell copies its DNA instruction book with complete accuracy every time it divides. And thus, with a few exceptions like the immune system, cells in normal, healthy tissue continue to contain exactly the same genome sequence as was present in the initial single-cell embryo that gave rise to that individual. But new evidence suggests it may be time to revise that view.

By analyzing genetic information collected throughout the bodies of nearly 500 different individuals, researchers discovered that almost all had some seemingly healthy tissue that contained pockets of cells bearing particular genetic mutations. Some even harbored mutations in genes linked to cancer. The findings suggest that nearly all of us are walking around with genetic mutations within various parts of our bodies that, under certain circumstances, may have the potential to give rise to cancer or other health conditions.

Efforts such as NIH’s The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) have extensively characterized the many molecular and genomic alterations underlying various types of cancer. But it has remained difficult to pinpoint the precise sequence of events that lead to cancer, and there are hints that so-called normal tissues, including blood and skin, might contain a surprising number of mutations —perhaps starting down a path that would eventually lead to trouble.

In the study published in Science, a team from the Broad Institute at MIT and Harvard, led by Gad Getz and postdoctoral fellow Keren Yizhak, along with colleagues from Massachusetts General Hospital, decided to take a closer look. They turned their attention to the NIH’s Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) project.

The GTEx is a comprehensive public resource that shows how genes are expressed and controlled differently in various tissues throughout the body. To capture those important differences, GTEx researchers analyzed messenger RNA sequences within thousands of healthy tissue samples collected from people who died of causes other than cancer.

Getz, Yizhak, and colleagues wanted to use that extensive RNA data in another way: to detect mutations that had arisen in the DNA genomes of cells within those tissues. To do it, they devised a method for comparing those tissue-derived RNA samples to the matched normal DNA. They call the new method RNA-MuTect.

All told, the researchers analyzed RNA sequences from 29 tissues, including heart, stomach, pancreas, and fat, and matched DNA from 488 individuals in the GTEx database. Those analyses showed that the vast majority of people—a whopping 95 percent—had one or more tissues with pockets of cells carrying new genetic mutations.

While many of those genetic mutations are most likely harmless, some have known links to cancer. The data show that genetic mutations arise most often in the skin, esophagus, and lung tissues. This suggests that exposure to environmental elements—such as air pollution in the lung, carcinogenic dietary substances in the esophagus, or the ultraviolet radiation in sunlight that hits the skin—may play important roles in causing genetic mutations in different parts of the body.

The findings clearly show that, even within normal tissues, the DNA in the cells of our bodies isn’t perfectly identical. Rather, mutations constantly arise, and that makes our cells more of a mosaic of different mutational events. Sometimes those altered cells may have a subtle growth advantage, and thus continue dividing to form larger groups of cells with slightly changed genomic profiles. In other cases, those altered cells may remain in small numbers or perhaps even disappear.

It’s not yet clear to what extent such pockets of altered cells may put people at greater risk for developing cancer down the road. But the presence of these genetic mutations does have potentially important implications for early cancer detection. For instance, it may be difficult to distinguish mutations that are truly red flags for cancer from those that are harmless and part of a new idea of what’s “normal.”

To further explore such questions, it will be useful to study the evolution of normal mutations in healthy human tissues over time. It’s worth noting that so far, the researchers have only detected these mutations in large populations of cells. As the technology advances, it will be interesting to explore such questions at the higher resolution of single cells.

Getz’s team will continue to pursue such questions, in part via participation in the recently launched NIH Pre-Cancer Atlas. It is designed to explore and characterize pre-malignant human tumors comprehensively. While considerable progress has been made in studying cancer and other chronic diseases, it’s clear we still have much to learn about the origins and development of illness to build better tools for early detection and control.

Reference:

[1] RNA sequence analysis reveals macroscopic somatic clonal expansion across normal tissues. Yizhak K, Aguet F, Kim J, Hess JM, Kübler K, Grimsby J, Frazer R, Zhang H, Haradhvala NJ, Rosebrock D, Livitz D, Li X, Arich-Landkof E, Shoresh N, Stewart C, Segrè AV, Branton PA, Polak P, Ardlie KG, Getz G. Science. 2019 Jun 7;364(6444).

Links:

Genotype-Tissue Expression Program

The Cancer Genome Atlas (National Cancer Institute/NIH)

Pre-Cancer Atlas (National Cancer Institute/NIH)

Getz Lab (Broad Institute, Cambridge, MA)

NIH Support: Common Fund; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; National Human Genome Research Institute; National Institute of Mental Health; National Cancer Institute; National Library of Medicine; National Institute on Drug Abuse; National Institute of Neurological Diseases and Stroke

Deciphering Secrets of Longevity, from Worms

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Caption: Long-lived worms show increased activation of DAF-16 (green), a protein linked with longevity in worms and humans.

Credit: Kapahi Lab, Buck Institute for Research on Aging, Novato, CA

How long would you want to live, if you could remain healthy? New clues from experiments done in microscopic worms suggest that science may have the potential to extend life spans dramatically.

Taking advantage of the power of the worm Caenorhabditis elegans (C. elegans) as a model system for genetic studies, NIH-funded researchers at the Buck Institute for Research on Aging in Novato, CA, decided to set about testing ways to extend the worms’ lifespan.

Fighting Obesity: New Hopes From Brown Fat

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Illustration: John MacNeill, based on patient imaging software designed by Ilan Tal. Copyright 2011 Joslin Diabetes Center

If you want to lose weight, then you actually want more fat, not less. But you need the right kind: brown fat. This special type of fatty tissue burns calories, puts out heat like a furnace, and helps to keep you trim. White fat, on the other hand, stores extra calories and makes you, well, fat. Wouldn’t it be nice if we could instruct our bodies to make more brown fat, and less white fat? Well, NIH-funded researchers have just taken another step in that direction [1].

New Understanding of a Common Kidney Cancer

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Caption: Histologic image of clear cell kidney cancer

Slide courtesy of W. Marston Linehan, National Cancer Institute, NIH

Understanding how cancer cells shift into high gear—what makes them become more aggressive and unresponsive to treatment—is a key concern of cancer researchers. A new study reveals how this escalation occurs in the most common form of kidney cancer: clear cell renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC). The study shows that ccRCC tumors acquire specific mutations that encourage uncontrollable growth and shifts in energy use and production [1].

Conducted by researchers in the NIH-led The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) Research Network, the study compared more than 400 ccRCC tumors from individual patients with healthy tissue samples from the same patients. Researchers were looking for differences in the gene activity and proteins in healthy vs. tumor tissue.

Next Page