computational biology

National Library of Medicine Helps Lead the Way in AI Research

Posted on by Patricia Flatley Brennan, R.N., Ph.D., National Library of Medicine

Did you know that the NIH’s National Library of Medicine (NLM) has been serving science and society since 1836? From its humble beginning as a small collection of books in the library of the U.S. Army Surgeon General’s office, NLM has grown not only to become the world’s largest biomedical library, but a leader in biomedical informatics and computational health data science research.

Think of NLM as a door through which you pass to connect with health data, literature, medical and scientific information, expertise, and sophisticated mathematical models or images that describe a clinical problem. This intersection of information, people, and technology allows NLM to foster discovery. NLM does so by ensuring that scientists, clinicians, librarians, patients, and the public have access to biomedical information 24 hours a day, 7 days a week.

The NLM also supports two research efforts: the Division of Extramural Programs (EP) and Intramural Research Program (IRP). Both programs are accelerating advances in biomedical informatics, data science, computational biology, and computational health. One of EP’s notable investments is focused on advancing artificial intelligence (AI) methods and reimagining how health care is delivered with the power of AI.

With support from NLM, Corey Lester and his colleagues at the University of Michigan College of Pharmacy, Ann Arbor, MI, are using AI to assist in pill verification, a standard procedure in pharmacies across the land. They want to help pharmacists avoid dangerous and costly dispensing errors. To do so, Lester is using AI to develop a real-time computer vision model. It views pills inside of a medication bottle, accurately identifies them, and determines that they are the correct or incorrect contents.

The IRP develops and applies computational methods and approaches to a broad range of information problems in biology, biomedicine, and human health. The IRP also offers intramural training opportunities and supports other training aimed at pre-baccalaureate to postdoctoral students and professionals.

The NLM principal investigators use biological data to advance computer algorithms and connect relationships between any level of biological organization and health conditions. They also use computational health sciences to focus on clinical information processing and analyze clinical data, assess clinical outcomes, and set health data standards.

NLM investigator Sameer Antani is collaborating with researchers in other NIH institutes to explore how AI can help us understand oral cancer, echocardiography, and pediatric tuberculosis. His research also is examining how images can be mined for data to predict the causes and outcomes of conditions. Examples of Antani’s work can be found in mobile radiology vehicles, which allow professionals to take chest X-rays (right) and screen for HIV and tuberculosis using software containing algorithms developed in his lab.

For AI to have its full impact, more algorithms and approaches that harness the power of data are needed. That’s why NLM supports hundreds of other intramural and extramural scientists who are addressing challenging health and biomedical problems. The NLM-funded research is focused on how AI can help people stay healthy through early disease detection, disease management, and clinical and treatment decision-making—all leading to the ultimate goal of helping people live healthier and happier lives.

The NLM is proud to lead the way in the use of AI to accelerate discovery and transform health care. Want to learn more? Follow me on Twitter. Or, you can follow my blog, NLM Musings from the Mezzanine and receive periodic NLM research updates.

I would like to thank Valerie Florance, Acting Scientific Director of NLM IRP, and Richard Palmer, Acting Director of NLM Division of EP, for their assistance with this post.

Links:

National Library of Medicine (National Library of Medicine/NIH)

Video: Using Machine Intelligence to Prevent Medication Dispensing Errors (NLM Funding Spotlight)

Video: Sameer Antani and Artificial Intelligence (NLM)

NLM Division of Extramural Programs (NLM)

NLM Intramural Research Program (NLM)

NLM Intramural Training Opportunities (NLM)

Principal Investigators (NLM)

NLM Musings from the Mezzanine (NLM)

Note: Dr. Lawrence Tabak, who performs the duties of the NIH Director, has asked the heads of NIH’s Institutes and Centers (ICs) to contribute occasional guest posts to the blog to highlight some of the interesting science that they support and conduct. This is the 20th in the series of NIH IC guest posts that will run until a new permanent NIH director is in place.

A More Precise Way to Knock Out Skin Rashes

Posted on by Lawrence Tabak, D.D.S., Ph.D.

The NIH is committed to building a new era in medicine in which the delivery of health care is tailored specifically to the individual person, not the hypothetical average patient as is now often the case. This new era of “precision medicine” will transform care for many life-threatening diseases, including cancer and chronic kidney disease. But what about non-life-threatening conditions, like the aggravating rash on your skin that just won’t go away?

Recently, researchers published a proof-of-principle paper in the journal Science Immunology demonstrating just how precision medicine for inflammatory skin rashes might work [1]. While more research is needed to build out and further refine the approach, the researchers show it’s now technologically possible to extract immune cells from a patient’s rash, read each cell’s exact inflammatory features, and relatively quickly match them online to the right anti-inflammatory treatment to stop the rash.

The work comes from a NIH-funded team led by Jeffrey Cheng and Raymond Cho, University of California, San Francisco. The researchers focused their attention on two inflammatory skin conditions: atopic dermatitis, the most common type of eczema, which flares up periodically to make skin red and itchy, and psoriasis vulgaris. Psoriasis causes skin cells to build up and form a scaly rash and dry, itchy patches. Together, atopic dermatitis and psoriasis vulgaris affect about 10 percent of U.S. adults.

While the rashes caused by the two conditions can sometimes look similar, they are driven by different sets of immune cells and underlying inflammatory responses. For that reason, distinct biologic therapies, based on antibodies and proteins made from living cells, are now available to target and modify the specific immune pathways underlying each condition.

While biologic therapies represent a major treatment advance for these and other inflammatory conditions, they can miss their targets. Indeed, up to half of patients don’t improve substantially on biologics. Part of the reason for that lack of improvement is because doctors don’t have the tools they need to make firm diagnoses based on what precisely is going on in the skin at the molecular and cellular levels.

To learn more in the new study, the researchers isolated immune cells, focusing primarily on T cells, from the skin of 31 volunteers. They then sequenced the RNA of each cell to provide a telltale portrait of its genomic features. This “single-cell analysis” allowed them to capture high-resolution portraits of 41 different immune cell types found in individual skin samples. That’s important because it offers a much more detailed understanding of changes in the behavior of various immune cells that might have been missed in studies focused on larger groupings of skin cells, representing mixtures of various cell types.

Of the 31 volunteers, seven had atopic dermatitis and eight had psoriasis vulgaris. Three others were diagnosed with other skin conditions, while six had an indeterminate rash with features of both atopic dermatitis and psoriasis vulgaris. Seven others were healthy controls.

The team produced molecular signatures of the immune cells. The researchers then compared the signatures from the hard-to-diagnose rashes to those of confirmed cases of atopic dermatitis and psoriasis. They wanted to see if the signatures could help to reach clearer diagnoses.

The signatures revealed common immunological features as well as underlying differences. Importantly, the researchers found that the signatures allowed them to move forward and classify the indeterminate rashes. The rashes also responded to biologic therapies corresponding to the individuals’ new diagnoses.

Already, the work has identified molecules that help to define major classes of human inflammatory skin diseases. The team has also developed computer tools to help classify rashes in many other cases where the diagnosis is otherwise uncertain.

In fact, the researchers have launched a pioneering website called RashX. It is enabling practicing dermatologists and researchers around the world to submit their single-cell RNA data from their difficult cases. Such analyses are now being done at a small, but growing, number of academic medical centers.

While precision medicine for skin rashes has a long way to go yet before reaching most clinics, the UCSF team is working diligently to ensure its arrival as soon as scientifically possible. Indeed, their new data represent the beginnings of an openly available inflammatory skin disease resource. They ultimately hope to generate a standardized framework to link molecular features to disease prognosis and drug response based on data collected from clinical centers worldwide. It’s a major effort, but one that promises to improve the diagnosis and treatment of many more unusual and long-lasting rashes, both now and into the future.

Reference:

[1] Classification of human chronic inflammatory skin disease based on single-cell immune profiling. Liu Y, Wang H, Taylor M, Cook C, Martínez-Berdeja A, North JP, Harirchian P, Hailer AA, Zhao Z, Ghadially R, Ricardo-Gonzalez RR, Grekin RC, Mauro TM, Kim E, Choi J, Purdom E, Cho RJ, Cheng JB. Sci Immunol. 2022 Apr 15;7(70):eabl9165. {Epub ahead of publication]

Links:

The Promise of Precision Medicine (NIH)

Atopic Dermatitis (National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases /NIH)

Psoriasis (NIAMS/NIH)

RashX (University of California, San Francisco)

Raymond Cho (UCSF)

Jeffrey Cheng (UCSF)

NIH Support: National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases; National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences

The Amazing Brain: Visualizing Data to Understand Brain Networks

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

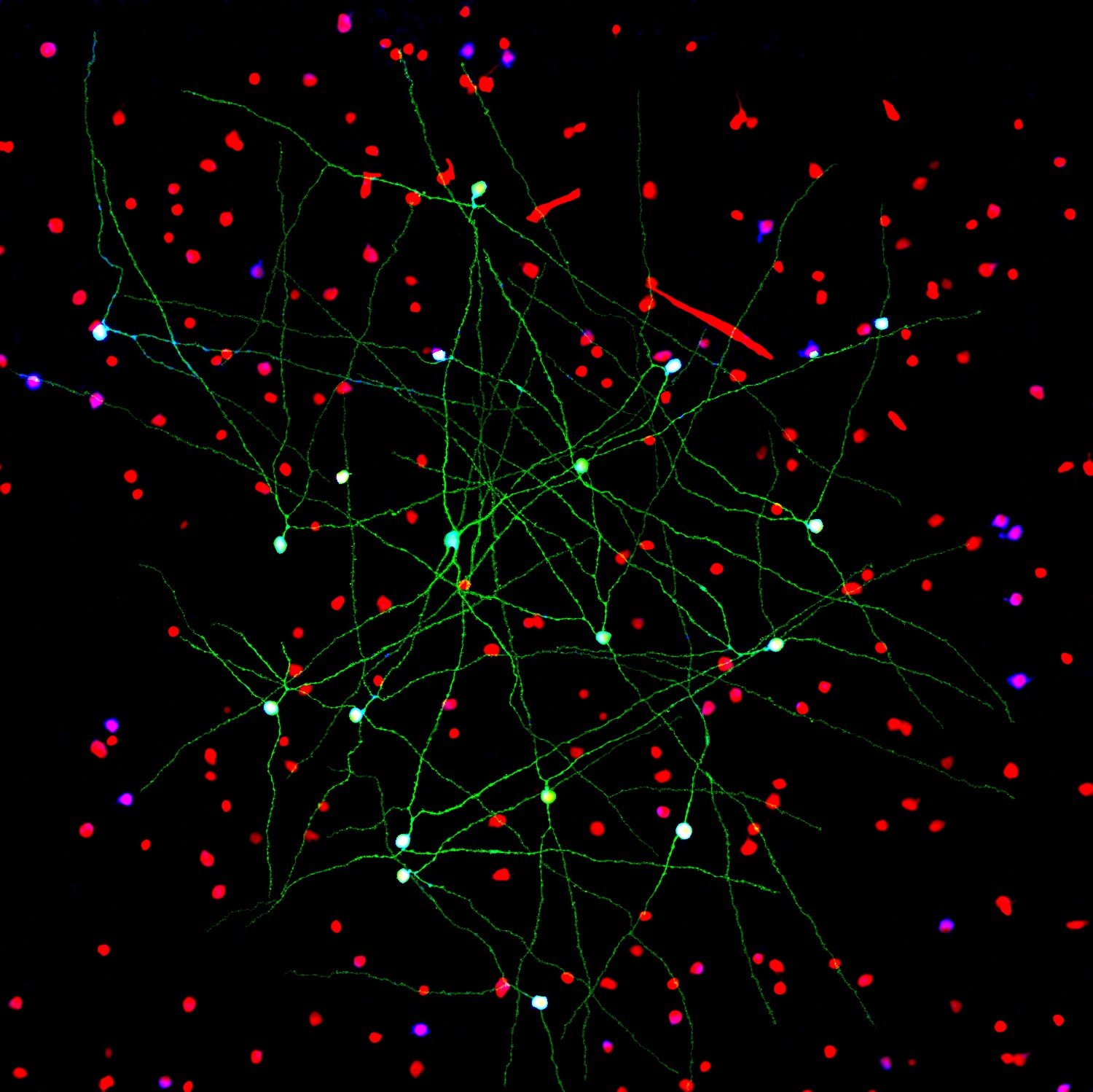

The NIH-led Brain Research through Advancing Innovative Neurotechnologies® (BRAIN) Initiative continues to teach us about the world’s most sophisticated computer: the human brain. This striking image offers a spectacular case in point, thanks to a new tool called Visual Neuronal Dynamics (VND).

VND is not a camera. It is a powerful software program that can display, animate, and analyze models of neurons and their connections, or networks, using 3D graphics. What you’re seeing in this colorful image is a strip of mouse primary visual cortex, the area in the brain where incoming sensory information gets processed into vision.

This strip contains more than 230,000 neurons of 17 different cell types. Long and spindly excitatory neurons that point upward (purple, blue, red, orange) are intermingled with short and stubby inhibitory neurons (green, cyan, magenta). Slicing through the neuronal landscape is a neuropixels probe (silver): a tiny flexible silicon detector that can record brain activity in awake animals [1].

Developed by Emad Tajkhorshid and his team at University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, along with Anton Arkhipov of the Allen Institute, Seattle, VND represents a scientific milestone for neuroscience: using an adept software tool to see and analyze massive neuronal datasets on a computer. What’s also nice is the computer doesn’t have to be a fancy one, and VND’s instructions, or code, are publicly available for anyone to use.

VND is the neuroscience-adapted cousin of Visual Molecular Dynamics (VMD), a popular molecular biology visualization tool to see life up close in 3D, also developed by Tajkhorshid’s group [2]. By modeling and visualizing neurons and their connections, VND helps neuroscientists understand at their desktops how neural networks are organized and what happens when they are manipulated. Those visualizations then lay the groundwork for follow-up lab studies to validate the data and build upon them.

Through the Allen Institute, the NIH BRAIN Initiative is compiling a comprehensive whole-brain atlas of cell types in the mouse, and Arkhipov’s work integrates these data into computer models. In May 2020, his group published comprehensive models of the mouse primary visual cortex [3].

Arkhipov and team are now working to understand how the primary visual cortex’s physical structure (the cell shapes and connections within its complicated circuits) determines its outputs. For example, how do specific connections determine network activity? Or, how fast do cells fire under different conditions?

Ultimately, such computational research may help us understand how brain injuries or disease affect the structure and function of these neural networks. VND should also propel understanding of many other areas of the brain, for which the data are accumulating rapidly, to answer similar questions that still remain mysterious to scientists.

In the meantime, VND is also creating some award-winning art. The image above was the second-place photo in the 2021 “Show us Your BRAINs!” Photo and Video Contest sponsored by the NIH BRAIN Initiative.

References:

[1] Fully integrated silicon probes for high-density recording of neural activity. Jun JJ, Steinmetz NA, Siegle JH, Denman DJ, Bauza M, Barbarits B, Lee AK, Anastassiou CA, Andrei A, Aydın Ç, Barbic M, Blanche TJ, Bonin V, Couto J, Dutta B, Gratiy SL, Gutnisky DA, Häusser M, Karsh B, Ledochowitsch P, Lopez CM, Mitelut C, Musa S, Okun M, Pachitariu M, Putzeys J, Rich PD, Rossant C, Sun WL, Svoboda K, Carandini M, Harris KD, Koch C, O’Keefe J, Harris TD. Nature. 2017 Nov 8;551(7679):232-236.

[2] VMD: visual molecular dynamics. Humphrey W, Dalke A, Schulten K. J Mol Graph. 1996 Feb;14(1):33-8, 27-8.

[3] Systematic integration of structural and functional data into multi-scale models of mouse primary visual cortex. Billeh YN, Cai B, Gratiy SL, Dai K, Iyer R, Gouwens NW, Abbasi-Asl R, Jia X, Siegle JH, Olsen SR, Koch C, Mihalas S, Arkhipov A. Neuron. 2020 May 6;106(3):388-403.e18

Links:

The Brain Research Through Advancing Innovative Neurotechnologies® (BRAIN) Initiative (NIH)

Models of the Mouse Primary Visual Cortex (Allen Institute, Seattle)

Visual Neuronal Dynamics (NIH Center for Macromolecular Modeling and Bioinformatics, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign)

Tajkhorshid Lab (University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign)

Arkhipov Lab (Allen Institute)

Show Us Your BRAINs! Photo & Video Contest (BRAIN Initiative/NIH)

NIH Support: National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke

Dynamic View of Spike Protein Reveals Prime Targets for COVID-19 Treatments

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

This striking portrait features the spike protein that crowns SARS-CoV-2, the coronavirus that causes COVID-19. This highly flexible protein has settled here into one of its many possible conformations during the process of docking onto a human cell before infecting it.

This portrait, however, isn’t painted on canvas. It was created on a computer screen from sophisticated 3D simulations of the spike protein in action. The aim was to map its many shape-shifting maneuvers accurately at the atomic level in hopes of detecting exploitable structural vulnerabilities to thwart the virus.

For example, notice the many chain-like structures (green) that adorn the protein’s surface (white). They are sugar molecules called glycans that are thought to shield the spike protein by sweeping away antibodies. Also notice areas (purple) that the simulation identified as the most-attractive targets for antibodies, based on their apparent lack of protection by those glycans.

This work, published recently in the journal PLoS Computational Biology [1], was performed by a German research team that included Mateusz Sikora, Max Planck Institute of Biophysics, Frankfurt. The researchers used a computer application called molecular dynamics (MD) simulation to power up and model the conformational changes in the spike protein on a time scale of a few microseconds. (A microsecond is 0.000001 second.)

The new simulations suggest that glycans act as a dynamic shield on the spike protein. They liken them to windshield wipers on a car. Rather than being fixed in space, those glycans sweep back and forth to protect more of the protein surface than initially meets the eye.

But just as wipers miss spots on a windshield that lie beyond their tips, glycans also miss spots of the protein just beyond their reach. It’s those spots that the researchers suggest might be prime targets on the spike protein that are especially promising for the design of future vaccines and therapeutic antibodies.

This same approach can now be applied to identifying weak spots in the coronavirus’s armor. It also may help researchers understand more fully the implications of newly emerging SARS-CoV-2 variants. The hope is that by capturing this devastating virus and its most critical proteins in action, we can continue to develop and improve upon vaccines and therapeutics.

Reference:

[1] Computational epitope map of SARS-CoV-2 spike protein. Sikora M, von Bülow S, Blanc FEC, Gecht M, Covino R, Hummer G. PLoS Comput Biol. 2021 Apr 1;17(4):e1008790.

Links:

COVID-19 Research (NIH)

Mateusz Sikora (Max Planck Institute of Biophysics, Frankfurt, Germany)

The surprising properties of the coronavirus envelope (Interview with Mateusz Sikora), Scilog, November 16, 2020.

Finding New Genetic Mutations Amid Healthy Cells

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

You might recall learning in biology class that the cells constantly replicating and dividing in our bodies all carry the same DNA, inherited in equal parts from each parent. But it’s become increasingly clear in recent years that even seemingly healthy tissues contain neighborhoods of cells bearing their own acquired genetic mutations. The question is: What do all those altered cells mean for our health?

With support from a 2018 NIH Director’s New Innovator Award, Po-Ru Loh, Harvard Medical School, Boston, is on a quest to find out, though without the need for sequencing lots of DNA in his own lab. Loh will instead develop ultrasensitive computational tools to pick up on those often-subtle alterations within the vast troves of genomic data already stored in databases around the world.

How is that possible? The math behind it might be complex, but the underlying idea is surprisingly simple. His algorithms look for spots in the genome where a slight imbalance exists in the quantity of DNA inherited from mom versus dad.

Actually, Loh can’t tell from the data which parent provided any snippet of chromosomal DNA. But looking at DNA sequenced from a mixture of many cells, he can infer which stretches of DNA were most likely inherited together from a single parent.

Any slight skew in those quantities point the way to genomic territory where a tiny portion of chromosomal DNA either went missing or became duplicated in some cells. This common occurrence, especially in older adults, leads to a condition called genetic mosaicism, meaning that, contrary to most biology textbooks, all cells aren’t exactly the same.

By detecting those subtle imbalances in the data, Loh can pinpoint small DNA alterations, even when they occur in 1 in 1,000 cells collected from a person’s bloodstream, saliva, or tissues. That’s the kind of sensitivity that most scientists would not have thought possible.

Loh has already begun putting his new computational approach to work, as reported in Nature last year [1]. In DNA data from blood samples of more than 150,000 participants in the United Kingdom Biobank, his method uncovered well over 8,000 mosaic chromosomal alterations.

The study showed that some of those alterations were associated with an increased risk of developing blood cancers. However, it’s important to note that most people with evidence of mosaicism won’t go on to develop cancer. The researchers also made the unexpected discovery that some individuals carried genetic variants that made them more prone than others to pick up new mutations in their blood cells.

What’s especially exciting is Loh’s computational tools now make it possible to search for signs of mosaicism within all the genetic data that’s ever been generated. Even more importantly, these tools will allow Loh and other researchers to ask and answer important questions about the consequences of mosaicism for a wide range of diseases.

Reference:

[1] Insights into clonal haematopoiesis from 8,342 mosaic chromosomal alterations. Loh PR, Genovese G, Handsaker RE, Finucane HK, Reshef YA, Palamara PF, Birmann BM, Talkowski ME, Bakhoum SF, McCarroll SA, Price AL. Nature. 2018 Jul;559(7714):350-355.

Links:

Loh Lab (Harvard Medical School, Boston)

Loh Project Information (NIH RePORTER)

NIH Director’s New Innovator Award (Common Fund)

NIH Support: Common Fund; National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences

Some ‘Hospital-Acquired’ Infections Traced to Patient’s Own Microbiome

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Caption: New computational tool determines whether a gut microbe is the source of a hospital-acquired bloodstream infection

Credit: Fiona Tamburini, Stanford University, Palo Alto, CA

While being cared for in the hospital, a disturbingly large number of people develop potentially life-threatening bloodstream infections. It’s been thought that most of the blame lies with microbes lurking on medical equipment, health-care professionals, or other patients and visitors. And certainly that is often true. But now an NIH-funded team has discovered that a significant fraction of these “hospital-acquired” infections may actually stem from a quite different source: the patient’s own body.

In a study of 30 bone-marrow transplant patients suffering from bloodstream infections, researchers used a newly developed computational tool called StrainSifter to match microbial DNA from close to one-third of the infections to bugs already living in the patients’ large intestines [1]. In contrast, the researchers found little DNA evidence to support the notion that such microbes were being passed around among patients.

Creative Minds: Building Better Computational Models of Common Disease

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Hilary Finucane

Not so long ago, Hilary Finucane was a talented young mathematician about to complete a master’s degree in theoretical computer science. As much as she enjoyed exploring pure mathematics, Finucane had begun having second thoughts about her career choice. She wanted to use her gift for numbers in a way that would have more real-world impact.

The solution to her dilemma was, literally, standing right by her side. Her husband Yakir Reshef, also a mathematician, was developing a new algorithm at the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard, Cambridge, MA, to improve detection of unexpected associations in large data sets. So, Finucane helped the Broad team with modeling biomedical topics ranging from the gut microbiome to global health. That work led to her co-authoring a paper in the journal Science [1], providing a strong start to what’s shaping up to be a rewarding career in computational biology.

Next Page