Accelerating COVID-19 Therapeutic Interventions and Vaccines

Biomedical Research Leads Science’s 2021 Breakthroughs

Posted on by Lawrence Tabak, D.D.S., Ph.D.

Hi everyone, I’m Larry Tabak. I’ve served as NIH’s Principal Deputy Director for over 11 years, and I will be the acting NIH director until a new permanent director is named. In my new role, my day-to-day responsibilities will certainly increase, but I promise to carve out time to blog about some of the latest research progress on COVID-19 and any other areas of science that catch my eye.

I’ve also invited the directors of NIH’s Institutes and Centers (ICs) to join me in the blogosphere and write about some of the cool science in their research portfolios. I will publish a couple of posts to start, then turn the blog over to our first IC director. From there, I envision alternating between posts from me and from various IC directors. That way, we’ll cover a broad array of NIH science and the tremendous opportunities now being pursued in biomedical research.

Since I’m up first, let’s start where the NIH Director’s Blog usually begins each year: by taking a look back at Science’s Breakthroughs of 2021. The breakthroughs were formally announced in December near the height of the holiday bustle. In case you missed the announcement, the biomedical sciences accounted for six of the journal Science’s 10 breakthroughs. Here, I’ll focus on four biomedical breakthroughs, the ones that NIH has played some role in advancing, starting with Science’s editorial and People’s Choice top-prize winner:

Breakthrough of the Year: AI-Powered Predictions of Protein Structure

The biochemist Christian Anfinsen, who had a distinguished career at NIH, shared the 1972 Nobel Prize in Chemistry, for work suggesting that the biochemical interactions among the amino acid building blocks of proteins were responsible for pulling them into the final shapes that are essential to their functions. In his Nobel acceptance speech, Anfinsen also made a bold prediction: one day it would be possible to determine the three-dimensional structure of any protein based on its amino acid sequence alone. Now, with advances in applying artificial intelligence to solve biological problems—Anfinsen’s bold prediction has been realized.

But getting there wasn’t easy. Every two years since 1994, research teams from around the world have gathered to compete against each other in developing computational methods for predicting protein structures from sequences alone. A score of 90 or above means that a predicted structure is extremely close to what’s known from more time-consuming work in the lab. In the early days, teams more often finished under 60.

In 2020, a London-based company called DeepMind made a leap with their entry called AlphaFold. Their deep learning approach—which took advantage of 170,000 proteins with known structures—most often scored above 90, meaning it could solve most protein structures about as well as more time-consuming and costly experimental protein-mapping techniques. (AlphaFold was one of Science’s runner-up breakthroughs last year.)

This year, the NIH-funded lab of David Baker and Minkyung Baek, University of Washington, Seattle, Institute for Protein Design, published that their artificial intelligence approach, dubbed RoseTTAFold, could accurately predict 3D protein structures from amino acid sequences with only a fraction of the computational processing power and time that AlphaFold required [1]. They immediately applied it to solve hundreds of new protein structures, including many poorly known human proteins with important implications for human health.

The DeepMind and RoseTTAFold scientists continue to solve more and more proteins [1,2], both alone and in complex with other proteins. The code is now freely available for use by researchers anywhere in the world. In one timely example, AlphaFold helped to predict the structural changes in spike proteins of SARS-CoV-2 variants Delta and Omicron [3]. This ability to predict protein structures, first envisioned all those years ago, now promises to speed fundamental new discoveries and the development of new ways to treat and prevent any number of diseases, making it this year’s Breakthrough of the Year.

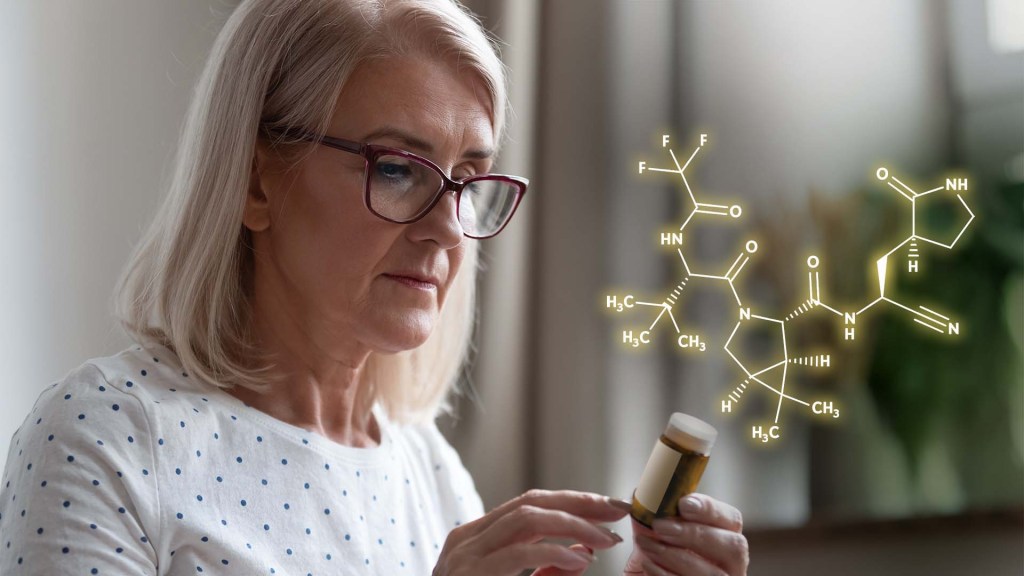

Anti-Viral Pills for COVID-19

The development of the first vaccines to protect against COVID-19 topped Science’s 2020 breakthroughs. This year, we’ve also seen important progress in treating COVID-19, including the development of anti-viral pills.

First, there was the announcement in October of interim data from Merck, Kenilworth, NJ, and Ridgeback Biotherapeutics, Miami, FL, of a significant reduction in hospitalizations for those taking the anti-viral drug molnupiravir [4] (originally developed with an NIH grant to Emory University, Atlanta). Soon after came reports of a Pfizer anti-viral pill that might target SARS-CoV-2, the novel coronavirus that causes COVID-19, even more effectively. Trial results show that, when taken within three days of developing COVID-19 symptoms, the pill reduced the risk of hospitalization or death in adults at high risk of progressing to severe illness by 89 percent [5].

On December 22, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) granted Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) for Pfizer’s Paxlovid to treat mild-to-moderate COVID-19 in people age 12 and up at high risk for progressing to severe illness, making it the first available pill to treat COVID-19 [6]. The following day, the FDA granted an EUA for Merck’s molnupiravir to treat mild-to-moderate COVID-19 in unvaccinated, high-risk adults for whom other treatment options aren’t accessible or recommended, based on a final analysis showing a 30 percent reduction in hospitalization or death [7].

Additional promising anti-viral pills for COVID-19 are currently in development. For example, a recent NIH-funded preclinical study suggests that a drug related to molnupiravir, known as 4’-fluorouridine, might serve as a broad spectrum anti-viral with potential to treat infections with SARS-CoV-2 as well as respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) [8].

Artificial Antibody Therapies

Before anti-viral pills came on the scene, there’d been progress in treating COVID-19, including the development of monoclonal antibody infusions. Three monoclonal antibodies now have received an EUA for treating mild-to-moderate COVID-19, though not all are effective against the Omicron variant [9]. This is also an area in which NIH’s Accelerating COVID-19 Therapeutic Interventions and Vaccines (ACTIV) public-private partnership has made big contributions.

Monoclonal antibodies are artificially produced versions of the most powerful antibodies found in animal or human immune systems, made in large quantities for therapeutic use in the lab. Until recently, this approach had primarily been put to work in the fight against conditions including cancer, asthma, and autoimmune diseases. That changed in 2021 with success using monoclonal antibodies against infections with SARS-CoV-2 as well as respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), and other infectious diseases. This earned them a prominent spot among Science’s breakthroughs of 2021.

Monoclonal antibodies delivered via intravenous infusions continue to play an important role in saving lives during the pandemic. But, there’s still room for improvement, including new formulations highlighted on the blog last year that might be much easier to deliver.

CRISPR Fixes Genes Inside the Body

One of the most promising areas of research in recent years has been gene editing, including CRISPR/Cas9, for fixing misspellings in genes to treat or even cure many conditions. This year has certainly been no exception.

CRISPR is a highly precise gene-editing system that uses guide RNA molecules to direct a scissor-like Cas9 enzyme to just the right spot in the genome to cut out or correct disease-causing misspellings. Science highlights a small study reported in The New England Journal of Medicine by researchers at Intellia Therapeutics, Cambridge, MA, and Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Tarrytown, NY, in which six people with hereditary transthyretin (TTR) amyloidosis, a condition in which TTR proteins build up and damage the heart and nerves, received an infusion of guide RNA and CRISPR RNA encased in tiny balls of fat [10]. The goal was for the liver to take them up, allowing Cas9 to cut and disable the TTR gene. Four weeks later, blood levels of TTR had dropped by at least half.

In another study not yet published, researchers at Editas Medicine, Cambridge, MA, injected a benign virus carrying a CRISPR gene-editing system into the eyes of six people with an inherited vision disorder called Leber congenital amaurosis 10. The goal was to remove extra DNA responsible for disrupting a critical gene expressed in the eye. A few months later, two of the six patients could sense more light, enabling one of them to navigate a dimly lit obstacle course [11]. This work builds on earlier gene transfer studies begun more than a decade ago at NIH’s National Eye Institute.

Last year, in a research collaboration that included former NIH Director Francis Collins’s lab at the National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI), we also saw encouraging early evidence in mice that another type of gene editing, called DNA base editing, might one day correct Hutchinson-Gilford Progeria Syndrome, a rare genetic condition that causes rapid premature aging. Preclinical work has even suggested that gene-editing tools might help deliver long-lasting pain relief. The technology keeps getting better, too. This isn’t the first time that gene-editing advances have landed on Science’s annual Breakthrough of the Year list, and it surely won’t be the last.

The year 2021 was a difficult one as the pandemic continued in the U.S. and across the globe, taking far too many lives far too soon. But through it all, science has been relentless in seeking and finding life-saving answers, from the rapid development of highly effective COVID-19 vaccines to the breakthroughs highlighted above.

As this list also attests, the search for answers has progressed impressively in other research areas during these difficult times. These groundbreaking discoveries are something in which we can all take pride—even as they encourage us to look forward to even bigger breakthroughs in 2022. Happy New Year!

References:

[1] Accurate prediction of protein structures and interactions using a three-track neural network. Baek M, DiMaio F, Anishchenko I, Dauparas J, Grishin NV, Adams PD, Read RJ, Baker D., et al. Science. 2021 Jul 15:eabj8754.

[2] Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Jumper J, Evans R, Pritzel A, Green T, Senior AW, Kavukcuoglu K, Kohli P, Hassabis D. et al. Nature. 2021 Jul 15.

[3] Structural insights of SARS-CoV-2 spike protein from Delta and Omicron variants. Sadek A, Zaha D, Ahmed MS. preprint bioRxiv. 2021 Dec 9.

[5] Pfizer’s novel COVID-19 oral antiviral treatment candidate reduced risk of hospitalization or death by 89% in interim analysis of phase 2/3 EPIC-HR Study. Pfizer. 5 November 52021.

[6] Coronavirus (COVID-19) Update: FDA authorizes first oral antiviral for treatment of COVID-19. Food and Drug Administration. 22 Dec 2021.

[7] Coronavirus (COVID-19) Update: FDA authorizes additional oral antiviral for treatment of COVID-19 in certain adults. Food and Drug Administration. 23 Dec 2021.

[8] 4′-Fluorouridine is an oral antiviral that blocks respiratory syncytial virus and SARS-CoV-2 replication. Sourimant J, Lieber CM, Aggarwal M, Cox RM, Wolf JD, Yoon JJ, Toots M, Ye C, Sticher Z, Kolykhalov AA, Martinez-Sobrido L, Bluemling GR, Natchus MG, Painter GR, Plemper RK. Science. 2021 Dec 2.

[9] Anti-SARS-CoV-2 monoclonal antibodies. NIH COVID-19 Treatment Guidelines. 16 Dec 2021.

[10] CRISPR-Cas9 in vivo gene editing for transthyretin amyloidosis. Gillmore JD, Gane E, Taubel J, Kao J, Fontana M, Maitland ML, Seitzer J, O’Connell D, Walsh KR, Wood K, Phillips J, Xu Y, Amaral A, Boyd AP, Cehelsky JE, McKee MD, Schiermeier A, Harari O, Murphy A, Kyratsous CA, Zambrowicz B, Soltys R, Gutstein DE, Leonard J, Sepp-Lorenzino L, Lebwohl D. N Engl J Med. 2021 Aug 5;385(6):493-502.

[11] Editas Medicine announces positive initial clinical data from ongoing phase 1/2 BRILLIANCE clinical trial of EDIT-101 For LCA10. Editas Medicine. 29 Sept 2021.

Links:

Structural Biology (National Institute of General Medical Sciences/NIH)

The Structures of Life (NIGMS)

COVID-19 Research (NIH)

2021 Science Breakthrough of the Year (American Association for the Advancement of Science, Washington, D.C)

Share this:

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Telegram (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window)

- Click to print (Opens in new window)

Posted In: News

Tags: 4'-fluorouridine, Accelerating COVID-19 Therapeutic Interventions and Vaccines, ACTIV, AI, AlphaFold, amino acids, artificial antibodies, artificial intelligence, biochemistry, Christian Anfinsen, Chronic Pain, computational biology, coronavirus, COVID pill, COVID-19, CRISPR, CRISPR/Cas9, DeepMind, Delta variant, Editas Medicine, EUA, gene editing, hereditary transthyretin amyloidosis, Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome, Intellia Therapeutics, Leber congenital amaurosis, Merck, molnupiravir, monoclonal antibodies, Omicron variant, pandemic, Pfizer, progeria, protein structure, rare disease, Regeneron, RoseTTAFold, SARS-CoV-2, Science Breakthrough of the Year, Science Breakthroughs of 2021, structural biology

Feeling Grateful This Thanksgiving for Biomedical Research

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Yes, we can all agree that 2021 has been a tough year. But despite all that, Thanksgiving is the right time to stop and count our many blessings. My list starts with my loving wife Diane and family, all of whom have been sources of encouragement in these trying times. But also high up on the list this Thanksgiving is my extreme gratitude to the scientific community for all the research progress that has been made over the past 23 months to combat the pandemic and return our lives ever closer to normal.

Last year, we were busy learning how to celebrate a virtual Thanksgiving. This year, most of us are feeling encouraged about holding face-to-face gatherings once again—but carefully!—and coordinating which dishes to prepare for the annual feast.

The COVID-19 vaccines, developed by science in record time and with impressive safety and effectiveness, have made this possible. The almost 230 million Americans who have chosen to receive at least one dose of a COVID-19 vaccine have taken a critical step to protect themselves and others. They have made this season a much safer one for themselves and those around them than a year ago. That includes almost all adults ages 65 and up. While vaccination rates aren’t yet as high as they need to be in younger age groups, about 70 percent of Americans ages 12 and up are now fully vaccinated.

But with evidence that the effectiveness of the vaccines can wane over time and with the continued threat of the Delta variant, I was happy to see the recent approval by both FDA and CDC that all adults 18 and over are now eligible to receive a booster. That is, provided you are now more than 6 months past your initial immunization with the Moderna or Pfizer or 2 months past your immunization with the Johnson & Johnson vaccine. I recently got my Moderna booster and I’m glad for that additional protection. Don’t wait—the booster is the best way to defend against a possible winter surge.

Children age 5 and up are also now eligible to get the Pfizer vaccine, a development that I know brought a sense of relief and gratitude for many parents with school-aged children at home. It will take a little time for full vaccination of this age group. But more than 2.5 million young kids around the country already have rolled up their sleeves and have some immunity against COVID-19. These children are on track to be fully vaccinated before Christmas.

I’m also extremely grateful for all the progress that’s been made in treating COVID-19. Developing new treatments typically takes many years, if not decades. But NIH’s Accelerating COVID-19 Therapeutic Interventions and Vaccines (ACTIV) initiative, a public-private partnership involving 20 biopharmaceutical companies, academic experts, and multiple federal agencies, has helped lead the way to this rapid progress.

We’ve seen successes in the use of monoclonal antibodies and in the repurposing of existing drugs, such as blood thinning treatments, to keep folks hospitalized with COVID-19 from becoming severely ill and needing some form of organ support. Now it looks as though our hopes for safe and effective oral antiviral medicines to reduce the risk of severe illness in individuals just diagnosed with COVID-19 could soon be realized, too.

To combat COVID-19, rapid and readily accessible testing also is key, and NIH’s Rapid Acceleration of Diagnostics (RADx®) initiative continues to speed innovation in COVID-19 testing. RADx® also recently launched a simple online calculator tool to help individuals make critical decisions about when to get a test [1]. Meanwhile, a new initiative called Say Yes! COVID Test (SYCT) is exploring how best to implement home-testing programs in our communities.

More research progress is on the way. But, until the pandemic is history, please remember to stay safe this holiday season. The best way to do so is to get fully vaccinated [2]. As I noted above, most adults who got vaccinated earlier this year are now eligible for a booster shot to ensure they remain well protected. Go to vaccines.gov to find the site closest to you that can provide the shot.

The best way to protect young children who aren’t yet eligible or fully vaccinated and others who may be at higher risk is by making sure you and others around them are vaccinated. It’s still strongly recommended to wear a well-fitting mask over your nose and mouth when in public indoor settings, especially if there’s considerable spread of COVID-19 in your community.

If you are gathering with multiple households or people from different parts of the country, consider getting tested for COVID-19 in advance and take extra precautions before traveling. By taking full advantage of all the many scientific advances we’ve made over the last year, we can now feel good about celebrating together again this holiday season. Happy Thanksgiving!

References:

[1] When to Test offers free online tool to help individuals make informed COVID-19 testing decisions. National Institutes of Health. November 3, 2021.

[2] Safer ways to celebrate holidays. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. October 15, 2021.

Links:

COVID-19 Research (NIH)

Accelerating COVID-19 Therapeutic Interventions and Vaccines (ACTIV) (NIH)

Rapid Acceleration of Diagnostics (RADx®) (NIH)

When To Test (Consortia for Improving Medicine with Innovation & Technology, Boston)

Share this:

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Telegram (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window)

- Click to print (Opens in new window)

Posted In: Generic

Tags: Accelerating COVID-19 Therapeutic Interventions and Vaccines, ACTIV, booster shot, COVID pill, COVID-19, COVID-19 vaccine, Johnson & Johnson vaccine, Moderna vaccine, novel coronavirus, pandemic, Pfizer, Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine, RADx, Rapid Acceleration of Diagnostics Initiative, SARS-CoV-2, Say Yes! COVID Test, Thanksgiving, vaccines.gov

Early Data Suggest Pfizer Pill May Prevent Severe COVID-19

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Over the course of this pandemic, significant progress has been made in treating COVID-19 and helping to save lives. That progress includes the development of life-preserving monoclonal antibody infusions and repurposing existing drugs, to which NIH’s Accelerating COVID-19 Therapeutic Interventions and Vaccines (ACTIV) public-private partnership has made a major contribution.

But for many months we’ve had hopes that a safe and effective oral medicine could be developed that would reduce the risk of severe illness for individuals just diagnosed with COVID-19. The first indication that those hopes might be realized came from the announcement just a month ago of a 50 percent reduction in hospitalizations from the Merck and Ridgeback drug molnupiravir (originally developed with an NIH grant to Emory University, Atlanta). Now comes word of a second drug with potentially even higher efficacy: an antiviral pill from Pfizer Inc. that targets a different step in the life cycle of SARS-CoV-2, the novel coronavirus that causes COVID-19.

The most recent exciting news started to roll out earlier this month when a Pfizer research team published in the journal Science some promising initial data involving the antiviral pill and its active compound [1]. Then came even bigger news a few days later when Pfizer announced interim results from a large phase 2/3 clinical trial. It found that, when taken within three days of developing symptoms of COVID-19, the pill reduced by 89 percent the risk of hospitalization or death in adults at high risk of progressing to severe illness [2].

At the recommendation of the clinical trial’s independent data monitoring committee and in consultation with the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), Pfizer has now halted the study based on the strength of the interim findings. Pfizer plans to submit the data to the FDA for Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) very soon.

Pfizer’s antiviral pill is a protease inhibitor, originally called PF-07321332, or just 332 for short. A protease is an enzyme that cleaves a protein at a specific series of amino acids. The SARS-CoV-2 virus encodes its own protease to help process a large virally-encoded polyprotein into smaller segments that it needs for its life cycle; a protease inhibitor drug can stop that from happening. If the term protease inhibitor rings a bell, that’s because drugs that work in this way already are in use to treat other viruses, including human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and hepatitis C virus.

In the case of 332, it targets a protease called Mpro, also called the 3CL protease, coded for by SARS-CoV-2. The virus uses this enzyme to snip some longer viral proteins into shorter segments for use in replication. With Mpro out of action, the coronavirus can’t make more of itself to infect other cells.

What’s nice about this therapeutic approach is that mutations to SARS-CoV-2’s surface structures, such as the spike protein, should not affect a protease inhibitor’s effectiveness. The drug targets a highly conserved, but essential, viral enzyme. In fact, Pfizer originally synthesized and pre-clinically evaluated protease inhibitors years ago as a potential treatment for severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), which is caused by a coronavirus closely related to SARS-CoV-2. This drug might even have efficacy against other coronaviruses that cause the common cold.

In the study published earlier this month in Science [1], the Pfizer team led by Dafydd Owen, Pfizer Worldwide Research, Cambridge, MA, reported that the latest version of their Mpro inhibitor showed potent antiviral activity in laboratory tests against not just SARS-CoV-2, but all of the coronaviruses they tested that are known to infect people. Further study in human cells and mouse models of SARS-CoV-2 infection suggested that the treatment might work to limit infection and reduce damage to lung tissue.

In the paper in Science, Owen and colleagues also reported the results of a phase 1 clinical trial with six healthy people. They found that their protease inhibitor, when taken orally, was safe and could reach concentrations in the bloodstream that should be sufficient to help combat the virus.

But would it work to treat COVID-19 in an infected person? So far, the preliminary results from the larger clinical trial of the drug candidate, now known as PAXLOVID™, certainly look encouraging. PAXLOVID™ is a formulation that combines the new protease inhibitor with a low dose of an existing drug called ritonavir, which slows the metabolism of some protease inhibitors and thereby keeps them active in the body for longer periods of time.

The phase 2/3 clinical trial included about 1,200 adults from the United States and around the world who had enrolled in the clinical trial. To be eligible, study participants had to have a confirmed diagnosis of COVID-19 within a five-day period along with mild-to-moderate symptoms of illness. They also required at least one characteristic or condition associated with an increased risk for developing severe illness from COVID-19. Each individual in the study was randomly selected to receive either the experimental antiviral or a placebo every 12 hours for five days.

In people treated within three days of developing COVID-19 symptoms, the Pfizer announcement reports that 0.8 percent (3 of 389) of those who received PAXLOVID™ were hospitalized within 28 days compared to 7 percent (27 of 385) of those who got the placebo. Similarly encouraging results were observed in those who got the treatment within five days of developing symptoms. One percent (6 of 607) on the antiviral were hospitalized versus 6.7 percent (41 of 612) in the placebo group. Overall, there were no deaths among people taking PAXLOVID™; 10 people in the placebo group (1.6 percent) subsequently died.

If all goes well with the FDA review, the hope is that PAXLOVID™ could be prescribed as an at-home treatment to prevent severe illness, hospitalization, and deaths. Pfizer also has launched two additional trials of the same drug candidate: one in people with COVID-19 who are at standard risk for developing severe illness and another evaluating its ability to prevent infection in adults exposed to the coronavirus by a household member.

Meanwhile, Britain recently approved the other recently developed antiviral molnupiravir, which slows viral replication in a different way by blocking its ability to copy its RNA genome accurately. The FDA will meet on November 30 to discuss Merck and Ridgeback’s request for an EUA for molnupiravir to treat mild-to-moderate COVID-19 in infected adults at high risk for severe illness [3]. With Thanksgiving and the winter holidays fast approaching, these two promising antiviral drugs are certainly more reasons to be grateful this year.

References:

[1] An oral SARS-CoV-2 M(pro) inhibitor clinical candidate for the treatment of COVID-19.

Owen DR, Allerton CMN, Anderson AS, Wei L, Yang Q, Zhu Y, et al. Science. 2021 Nov 2: eabl4784.

[2] Pfizer’s novel COVID-19 oral antiviral treatment candidate reduced risk of hospitalization or death by 89% in interim analysis of phase 2/3 EPIC-HR Study. Pfizer. November 5, 2021.

[3] FDA to hold advisory committee meeting to Discuss Merck and Ridgeback’s EUA Application for COVID-19 oral treatment. Food and Drug Administration. October 14, 2021.

Links:

COVID-19 Research (NIH)

Accelerating COVID-19 Therapeutic Interventions and Vaccines (ACTIV) (NIH)

A Study of PF-07321332/Ritonavir in Nonhospitalized Low-Risk Adult Participants With COVID-19 (ClinicalTrials.gov)

A Post-Exposure Prophylaxis Study of PF-07321332/Ritonavir in Adult Household Contacts of an Individual With Symptomatic COVID-19 (ClinicalTrials.gov)

Share this:

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Telegram (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window)

- Click to print (Opens in new window)

Posted In: News

Tags: 332, 3CL protease, Accelerating COVID-19 Therapeutic Interventions and Vaccines, ACTIV, antivirals, clinical trial, coronavirus, COVID pill, COVID-19, COVID-19 treatment, drug development, Emergency Use Authorization, EUA, FDA, Merck, molnupiravir, Mpro, novel coronavirus, pandemic, PAXLOVID™, PF-07321332, Pfizer, protease, protease inhibitor, Ridgeback, ritonavir, SARS, SARS-CoV-2, spike protein

ACTIV Update: Making Major Strides in COVID-19 Therapeutic Development

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Right now, many U.S. hospitals are stretched to the limit trying to help people battling serious cases of COVID-19. But as traumatic as this experience still is for patients and their loved ones, the chances of surviving COVID-19 have in fact significantly improved in the year since the start of the pandemic.

This improvement stems from several factors, including the FDA’s emergency use authorization (EUA) of a number of therapies found to be safe and effective for COVID-19. These include drugs that you may have heard about on the news: remdesivir (an antiviral), dexamethasone (a steroid), and monoclonal antibodies from the companies Eli Lilly and Regeneron.

Yet the quest to save more lives from COVID-19 isn’t even close to being finished, and researchers continue to work intensively to develop new and better treatments. A leader in this critical effort is NIH’s Accelerating COVID-19 Therapeutic Interventions and Vaccines (ACTIV) initiative, a public-private partnership involving 20 biopharmaceutical companies, academic experts, and multiple federal agencies.

ACTIV was founded last April to accelerate drug research that typically requires more than a decade of clinical ups and downs to develop a safe, effective therapy. And ACTIV has indeed moved at unprecedented speed since its launch. Cutting through the usual red tape and working with an intense sense of purpose, the partnership took a mere matter of weeks to set up its first four clinical trials. Beyond the agents mentioned above that have already been granted an EUA, ACTIV is testing 15 additional potential agents, with several of these already demonstrating promising results.

Here’s how ACTIV works. The program relies on four expert “working groups” with specific charges:

Preclinical Working Group: Shares standardized preclinical evaluation resources and accelerate testing of candidate therapies and vaccines for clinical trials.

Therapeutics Clinical Working Group: Prioritizes therapeutic agents for testing within an adaptive master protocol strategy for clinical research.

Clinical Trial Capacity Working Group: Has developed and organized an inventory of clinical trial capacity that can serve as potential settings in which to implement effective COVID-19 clinical trials.

Vaccines Working Group: Accelerates the evaluation of vaccine candidates.

To give you just one example of how much these expert bodies have accomplished in record time, the Therapeutics Clinical Working Group got to work immediately evaluating some 400 candidate therapeutics using multiple publicly available information sources. These candidates included antivirals, host-targeted immune modulators, monoclonal antibodies (mAb), and symptomatic/supportive agents including anticoagulants. To follow up on even more new leads, the working group launched a COVID-19 Clinical & Preclinical Candidate Compound Portal, which remains open for submissions of therapeutic ideas and data.

All the candidate agents have been prioritized using rigorous scoring and assessment criteria. What’s more, the working group simultaneously developed master protocols appropriate for each of the drug classes selected and patient populations: outpatient, inpatient, or convalescent.

Through the coordinated efforts of all the working groups, here’s where we stand with the ACTIV trials:

ACTIV-1: A large-scale Phase 3 trial is enrolling hospitalized adults to test the safety and effectiveness of three medicines (cenicriviroc, abatacept, and infliximab). They are called immune modulators because they help to minimize the effects of an overactive immune response in some COVID-19 patients. This response, called a “cytokine storm,” can lead to acute respiratory distress syndrome, multiple organ failure, and other life-threatening complications.

ACTIV-2: A Phase 2/3 trial is enrolling adults with COVID-19 who are not hospitalized to evaluate the safety of multiple monoclonal antibodies (Lilly’s LY-CoV555, Brii Biosciences’s BRII-196 and BRII-198, and AstraZeneca’s AZD7442) used to block or neutralize the SARS-CoV-2 virus. The Lilly monoclonal antibody LY-CoV555 received an EUA for high risk non-hospitalized patients on November 9, 2020 and ACTIV-2 continued to test the agent in an open label study to further determine safety and efficacy in outpatients. Another arm of this trial has just started, testing inhaled, easy-to-administer interferon beta-1a treatment in adults with mild-to-moderate COVID-19 who are not hospitalized. An additional arm will test the drug camostat mesilate, a protease inhibitor that can block the TMPRSS2 host protein that is necessary for viral entry into human cells.

ACTIV-3: This Phase 3 trial is enrolling hospitalized adults with COVID-19. This study primarily aims to evaluate safety and to understand if monoclonal antibodies (AstraZeneca’s AZD7442, BRII-196 and BRII-198, and the VIR-7831 from GSK/Vir Biotechnology) and potentially other types of therapeutics can reduce time to recovery. It also aims to understand a treatment’s effect on extrapulmonary complications and respiratory dysfunction. Lilly’s monoclonal antibody LY-CoV555 was one of the first agents to be tested in this clinical trial and it was determined to not show the same benefits seen in outpatients. [Update: NIH-Sponsored ACTIV-3 Clinical Trial Closes Enrollment into Two Sub-Studies, March 4, 2021]

ACTIV-4: This trial aims to determine if various types of blood thinners, including apixaban, aspirin, and both unfractionated (UF) and low molecular weight (LMW) heparin, can treat adults diagnosed with COVID-19 and prevent life-threatening blood clots from forming. There are actually three Phase 3 trials included in ACTIV-4. One is enrolling people diagnosed with COVID-19 but who are not hospitalized; a second is enrolling patients who are hospitalized; and a third is enrolling people who are recovering from COVID-19. ACTIV-4 has already shown that full doses of heparin blood thinners are safe and effective for moderately ill hospitalized patients.

ACTIV-5: This is a Phase 2 trial testing newly identified agents that might have a major benefit to hospitalized patients with COVID-19, but that need further “proof of concept” testing before they move into a registrational Phase 3 trial. (In fact, another name for this trial is the “Big Effect Trial”.) It is testing medicines previously developed for other conditions that might be beneficial in treatment of COVID-19. The first two agents being tested are risankizumab (the result of a collaboration between Boehringer-Ingelheim), which is already FDA-approved to treat plaque psoriasis, and lenzilumab, which is under development by Humanigen to treat patients experiencing cytokine storm as part of cancer therapy.

In addition to trials conducted under the ACTIV partnership, NIH has prioritized and tested additional therapeutics in “ACTIV-associated trials.” These are NIH-funded, randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trials with one or more industry partners. Here’s a table with a comprehensive list.

Looking a bit further down the road, we also seek to develop orally administered drugs that would potentially block the replication ability of SARS-CoV-2, the coronavirus that causes COVID-19, in the earliest stages of infection. One goal would be to develop an antiviral medication for SARS-CoV-2 that acts similarly to oseltamivir phosphate (Tamiflu®), a drug used to shorten the course of the flu in people who’ve had symptoms for less than two days and to prevent the flu in asymptomatic people who may have been exposed to the influenza virus. Yet another major long-term effort of NIH and its partners will be to develop safe and effective antiviral medications that work against all coronaviruses, even those with variant genomes. (And, yes, such drugs might even cure the common cold!)

So, while our ACTIV partners and many other researchers around the globe continue to harness the power of science to end the devastating COVID-19 pandemic as soon as possible, we must also consider the lessons learned this past year, in order to prepare ourselves to respond more swiftly to future outbreaks of coronaviruses and other infectious disease threats. Our work is clearly a marathon, not a sprint.

Links:

Accelerating COVID-19 Therapeutic Interventions and Vaccines (ACTIV) (NIH)

COVID-19 Research (NIH)

Combat COVID (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Washington, D.C.)

Pull Up a Chair with Dr. Freire: The COVID Conversations (Foundation for the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD)

SARS-COV-2 Antiviral Therapeutics Summit Report, November 2020 (NIH)

Share this:

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Telegram (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window)

- Click to print (Opens in new window)

Posted In: News

Tags: Accelerating COVID-19 Therapeutic Interventions and Vaccines, ACTIV, antiviral, apixaban, aspirin, AstraZeneca, AZD7442, Big Effect Trial, blood clots, blood thinner, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Brii Bioscience, BRII-196, BRII-198, camostat mesilate, clinical trials, coronavirus, COVID-19, COVID-19 Clinical & Preclinical Candidate Compound Portal, COVID-19 treatment, COVID-19 vaccine, dexamethasone, drug development, Eli Lilly and Company, EUA, GSK/Vir Biotechnology, heparin, host-targeted immune modulator, Humanigen, immune modulator, lenzilumab, LY-CoV555, monoclonal antibody, novel coronavirus, oseltamivir phosphate, pandemic, public-private partnership, Regeneron, remdesivir, risankizumab, SARS-CoV-2, Tamiflu, therapeutics, TMPRSS2, treatments, VIR-7831

Can Blood Thinners Keep Moderately Ill COVID-19 Patients Out of the ICU?

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

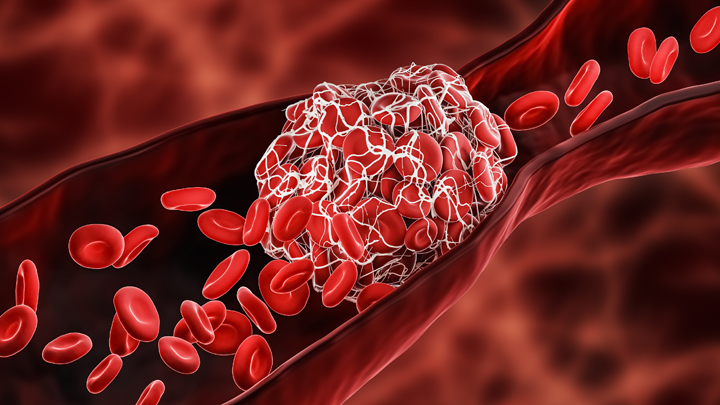

One of many troubling complications of infection with SARS-CoV-2, the coronavirus that causes COVID-19, is its ability to trigger the formation of multiple blood clots, most often in older people but sometimes in younger ones, too. It raises the question of whether and when more aggressive blood thinning treatments might improve outcomes for people hospitalized for COVID-19.

The answer to this question is desperately needed to help guide clinical practice. So, I’m happy to report interim results of three large clinical trials spanning four continents and more than 300 hospitals that are beginning to provide critical evidence on this very question [1]. While it will take time to reach a solid consensus, the findings based on more than 1,000 moderately ill patients suggest that full doses of blood thinners are safe and can help to keep folks hospitalized with COVID-19 from becoming more severely ill and requiring some form of organ support.

The results that are in so far suggest that individuals hospitalized, but not severely ill, with COVID-19 who received a full intravenous dose of the common blood thinner heparin were less likely to need vital organ support, including mechanical ventilation, compared to those who received the lower “prophylactic” subcutaneous dose. It’s important to note that these findings are in contrast to results announced last month indicating that routine use of a full dose of blood thinner for patients already critically ill and in the ICU wasn’t beneficial and may even have been harmful in some cases [2]. This is a compelling example of how critical it is to stratify patients with different severity in clinical trials—what might help one subgroup might be of no benefit, or even harmful, in another.

More study is clearly needed to sort out all the details about when more aggressive blood thinning treatment is warranted. Trial investigators are now working to make the full results available to help inform a doctor’s decisions about how to best to treat their patients hospitalized with COVID-19. It’s worth noting that these trials are overseen by independent review boards, which routinely evaluate the data and are composed of experts in ethics, biostatistics, clinical trials, and blood clotting disorders.

These clinical trials were made possible in part by the Accelerating COVID-19 Therapeutic Interventions and Vaccines (ACTIV) public-private partnership and its ACTIV-4 Antithrombotics trials—along with similar initiatives in Canada, Australia, and the European Union. The ACTIV-4 trials are overseen by the NIH’s National Heart, Lung, and Blood institute and funded by Operation Warp Speed.

This ACTIV-4 trial is one of three Phase 3 clinical trials evaluating the safety and effectiveness of blood thinners for patients with COVID-19 [3]. Another ongoing trial is investigating whether blood thinners are beneficial for newly diagnosed COVID-19 patients who do not require hospitalization. There are also plans to explore the use of blood thinners for patients after they’ve been discharged from the hospital following a diagnosis of moderate to severe COVID-19 and to establish more precise methods for identifying which patients with COVID-19 are most at risk for developing life-threatening blood clots.

Meanwhile, research teams are exploring other potentially promising ways to repurpose existing therapeutics and improve COVID-19 outcomes. In fact, the very day that these latest findings on blood thinners were announced, another group at The Montreal Heart Institute, Canada, announced preliminary results of the international COLCORONA trial, testing the use of colchicine—an anti-inflammatory drug widely used to treat gout and other conditions—for patients diagnosed with COVID-19 [4].

Their early findings in treating patients just after a confirmed diagnosis of COVID-19 suggest that colchicine might reduce the risk of death or hospitalization compared to patients given a placebo. In the more than 4,100 individuals with a proven diagnosis of COVID-19, colchicine significantly reduced hospitalizations by 25 percent, the need for mechanical ventilation by 50 percent, and deaths by 44 percent. Still, the actual numbers of individuals represented by these percentages was small.

Time will tell whether and for which patients colchicine and blood thinners prove most useful in treating COVID-19. For those answers, we’ll have to await the analysis of more data. But the early findings on both treatment strategies come as a welcome reminder that we continue to make progress each day on such critical questions about which existing treatments can be put to work to improve outcomes for people with COVID-19. Together with our efforts to slow the spread of SARS-CoV-2, finding better ways to treat those who do get sick and prevent some of the worst outcomes will help us finally put this terrible pandemic behind us.

References:

[1] Full-dose blood thinners decreased need for life support and improved outcome in hospitalized COVID-19 patients. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. January 22, 2021.

[2] NIH ACTIV trial of blood thinners pauses enrollment of critically ill COVID-19 patients. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. December 22, 2020.

[3] NIH ACTIV initiative launches adaptive clinical trials of blood-clotting treatments for COVID-19. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. September 10, 2020.

[4] Colchicine reduces the risk of COVID-19-related complications. The Montreal Heart Institute. January 22, 2021.

Links:

COVID-19 Research (NIH)

Combat COVID (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Washington, D.C.)

Accelerating COVID-19 Therapeutic Interventions and Vaccines (ACTIV) (NIH)

NIH Support: National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute

Share this:

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Telegram (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window)

- Click to print (Opens in new window)

Posted In: News

Tags: Accelerating COVID-19 Therapeutic Interventions and Vaccines, ACTIV, ACTIV-4, ACTIV-4 Antithrombotics trials, blood, blood clots, blood thinner, blood vessels, clinical trials, colchicine, COLCORONA trial, COVID-19, COVID-19 treatment, COVID-19-complications, heart, heparin, Montreal Heart Institute, novel coronavirus, pandemic, SARS-CoV-2, stroke

New Online Resource Shows How You Can Help to Fight COVID-19

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

There are lots of useful online resources to learn about COVID-19 and some of the clinical studies taking place across the country. What’s been missing is a one-stop online information portal that pulls together the most current information for people of all groups, races, ethnicities, and backgrounds who want to get involved in fighting the pandemic. So, I’m happy to share that the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, in coordination with NIH and Operation Warp Speed, has just launched a website called Combat COVID.

This easy-to-navigate portal makes it even easier for you and your loved ones to reach informed decisions about your health and to find out how to help in the fight against COVID-19. Indeed, it shows that no matter your current experience with COVID-19, there are opportunities to get involved to develop vaccines and medicines that will help everyone. Hundreds of thousands of volunteers have already taken this step—but we still need more, so we are seeking your help.

The Combat COVID website, which can also be viewed in Spanish, is organized to guide you to the most relevant information based on your own COVID-19 status:

• If you’ve never had COVID-19, you’ll be directed to information about joining the COVID-19 Prevention Network’s Volunteer Screening Registry. This registry is creating a list of potential volunteers willing to take part in ongoing or future NIH clinical trials focused on preventing COVID-19—like vaccines. Why get involved in a clinical trial now if vaccines will be widely distributed in the future? Well, there’s still a long way to go to get the pandemic under control, and several promising vaccines are still undergoing definitive testing. Your best route to getting access to a vaccine right now might be a clinical trial. And the more vaccines that are found to be safe and effective, the sooner we will be able to immunize all Americans and many others around the world.

• If you have an active COVID-19 infection, you’ll be directed to information about ongoing clinical trials that are studying better ways to treat the infection with promising drugs and other treatments. There are currently at least nine ongoing clinical trials for adults at every stage of COVID-19 illness. That includes five NIH Accelerating COVID-19 Therapeutic Interventions and Vaccines (ACTIV) public-private partnership trials. All of these are promising treatments, but need to be rigorously tested to be sure they are safe and effective.

• If you’ve recovered from a confirmed case of COVID-19, you may be able to give the gift of life to someone else. Check out Combat COVID, where you’ll be directed to information about how to donate blood plasma. Once donated, this plasma may be infused into another person to help treat COVID-19 or it may be used to make a potential medicine.

• For doctors treating people with COVID-19, the website also provides a collection of useful information, including details on how to connect patients to ongoing clinical trials and other opportunities to combat COVID-19.

While I’m discussing online resources, NIH’s National Cancer Institute (NCI) also recently launched an interesting website for a critical initiative called the Serological Sciences Network for COVID-19 (SeroNet). A collaboration between several NIH components and 25 of the nation’s top biomedical research institutions, SeroNet will increase the national capacity for antibody testing, while also investigating all aspects of the immune response to SARS-CoV-2, the coronavirus that causes COVID-19. That includes studying variations in the severity of COVID-19 symptoms, the influence of pre-existing conditions for developing severe disease, and the chances of reinfection.

In our efforts to combat COVID-19, we’ve come a long way in a short period of time. But there is still plenty of work to do to get the pandemic under control to protect ourselves, our loved ones, and our communities. Be a hero. Follow the three W’s: Wear a mask. Watch your distance (stay 6 feet apart). Wash your hands often. And, if you’d like to find what else you can do to help, follow your way to Combat COVID.

Links:

Coronavirus (COVID-19) (NIH)

Combat COVID (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Washington, D.C.)

Explaining Operation Warp Speed (HHS)

Accelerating COVID-19 Therapeutic Interventions and Vaccines (ACTIV) (NIH)

Serological Sciences Network for COVID-19 (SeroNet) (National Cancer Institute/NIH)

Share this:

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Telegram (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window)

- Click to print (Opens in new window)

Posted In: News

Tags: Accelerating COVID-19 Therapeutic Interventions and Vaccines, ACTIV, antibody, antibody testing, blood plasma, clinical trials, Combat COVID, coronavirus, COVID-19, COVID-19 prevention, COVID-19 Prevention Network, COVID-19 reinfection, drug development, novel coronavirus, online resources, Operation Warp Speed, pandemic, SARS-CoV-2, Serological Sciences Network for COVID-19, SeroNet, vaccine, website

Charting a Rapid Course Toward Better COVID-19 Tests and Treatments

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

It is becoming apparent that our country is entering a new and troubling phase of the pandemic as SARS-CoV-2, the novel coronavirus that causes COVID-19, continues to spread across many states and reaches into both urban and rural communities. This growing community spread is hard to track because up to 40 percent of infected people seem to have no symptoms. They can pass the virus quickly and unsuspectingly to friends and family members who might be more vulnerable to becoming seriously ill. That’s why we should all be wearing masks when we go out of the house—none of us can be sure we’re not that asymptomatic carrier of the virus.

This new phase makes fast, accessible, affordable diagnostic testing a critical first step in helping people and communities. In recognition of this need, NIH’s Rapid Acceleration of Diagnostics (RADx) initiative, just initiated in late April, has issued an urgent call to the nation’s inventors and innovators to develop fast, easy-to-use tests for SARS-CoV-2, the novel coronavirus that causes COVID-19. It brought a tremendous response, and NIH selected about 100 of the best concepts for an intense one-week “shark-tank” technology evaluation process.

Moving ahead at an unprecedented pace, NIH last week announced the first RADx projects to come through the deep dive with flying colors and enter the scale-up process necessary to provide additional rapid testing capacity to the U.S. public. As part of the RADx initiative, seven biomedical technology companies will receive a total of $248.7 million in federal stimulus funding to accelerate their efforts to scale up new lab-based and point-of-care technologies.

Four of these projects will aim to bolster the nation’s lab-based COVID-19 diagnostics capacity by tens of thousands of tests per day as soon as September and by millions by the end of the year. The other three will expand point-of-care testing for COVID-19, making results more rapidly and readily available in doctor’s offices, urgent care clinics, long-term care facilities, schools, child care centers, or even at home.

This is only a start, and we expect that more RADx projects will advance in the coming months and begin scaling up for wide-scale use. In the meantime, here’s an overview of the first seven projects developed through the initiative, which NIH is carrying out in partnership with the Office of the Assistant Secretary of Health, the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority, and the Department of Defense:

Point-of-Care Testing Approaches

Mesa Biotech. Hand-held testing device detects the genetic material of SARS-CoV-2. Results are read from a removable, single-use cartridge in 30 minutes.

Quidel. Test kit detects protein (viral antigen) from SARS-CoV-2. Electronic analyzers provide results within 15 minutes. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Service has identified this technology for possible use in nursing homes.

Talis Biomedical. Compact testing instrument uses a multiplexed cartridge to detect the genetic material of SARS-CoV-2 through isothermal amplification. Optical detection system delivers results in under 30 minutes.

Lab-based Testing Approaches

Ginkgo Bioworks. Automated system uses next-generation sequencing to scan patient samples for SARS-CoV-2’s genetic material. This system will be scaled up to make it possible to process tens of thousands of tests simultaneously and deliver results within one to two days. The company’s goal is to scale up to 50,000 tests per day in September and 100,000 per day by the end of 2020.

Helix OpCo. By combining bulk shipping of test kits and patient samples, automation, and next-generation sequencing of genetic material, the company’s goal is to process up to 50,000 samples per day by the end of September and 100,000 per day by the end of 2020.

Fluidigm. Microfluidics platform with the capacity to process thousands of polymerase chain reaction (PCR) tests for SARS-CoV-2 genetic material per day. The company’s goal is to scale up this platform and deploy advanced integrated fluidic chips to provide tens to hundreds of thousands of new tests per day in the fall of 2020. Most tests will use saliva.

Mammoth Biosciences. System uses innovative CRISPR gene-editing technology to detect key pieces of SARS-CoV-2 genetic material in patient samples. The company’s goal is to provide a multi-fold increase in testing capacity in commercial laboratories.

At the same time, on the treatment front, significant strides continue to be made by a remarkable public-private partnership called Accelerating COVID-19 Therapeutic Interventions and Vaccines (ACTIV). Since its formation in May, the partnership, which involves 20 biopharmaceutical companies, academic experts, and multiple federal agencies, has evaluated hundreds of therapeutic agents with potential application for COVID-19 and prioritized the most promising candidates.

Among the most exciting approaches are monoclonal antibodies (mAbs), which are biologic drugs derived from neutralizing antibodies isolated from people who’ve survived COVID-19. This week, the partnership launched two trials (one for COVID-19 inpatients, the other for COVID-19 outpatients) of a mAB called LY-CoV555, which was developed by Eli Lilly and Company, Indianapolis, IN. It was discovered by Lilly’s development partner AbCellera Biologics Inc. Vancouver, Canada, in collaboration with the NIH’s National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID). In addition to the support from ACTIV, both of the newly launched studies also receive support for Operation Warp Speed, the government’s multi-agency effort against COVID-19.

LY-CoV555 was derived from the immune cells of one of the very first survivors of COVID-19 in the United States. It targets the spike protein on the surface of SARS-CoV-2, blocking it from attaching to human cells.

The first trial, which will look at both the safety and efficacy of the mAb for treating COVID-19, will involve about 300 individuals with mild to moderate COVID-19 who are hospitalized at facilities that are part of existing clinical trial networks. These volunteers will receive either an intravenous infusion of LY-CoV555 or a placebo solution. Five days later, their condition will be evaluated. If the initial data indicate that LY-CoV555 is safe and effective, the trial will transition immediately—and seamlessly—to enrolling an additional 700 participants with COVID-19, including some who are severely ill.

The second trial, which will evaluate how LY-CoV555 affects the early course of COVID-19, will involve 220 individuals with mild to moderate COVID-19 who don’t need to be hospitalized. In this study, participants will randomly receive either an intravenous infusion of LY-CoV555 or a placebo solution, and will be carefully monitored over the next 28 days. If the data indicate that LY-CoV555 is safe and shortens the course of COVID-19, the trial will then enroll an additional 1,780 outpatient volunteers and transition to a study that will more broadly evaluate its effectiveness.

Both trials are later expected to expand to include other experimental therapies under the same master study protocol. Master protocols allow coordinated and efficient evaluation of multiple investigational agents at multiple sites as the agents become available. These protocols are designed with a flexible, rapidly responsive framework to identify interventions that work, while reducing administrative burden and cost.

In addition, Lilly this week started a separate large-scale safety and efficacy trial to see if LY-CoV555 can be used to prevent COVID-19 in high-risk residents and staff at long-term care facilities. The study isn’t part of ACTIV.

NIH-funded researchers have been extremely busy over the past seven months, pursuing every avenue we can to detect, treat, and, ultimately, end this devasting pandemic. Far more work remains to be done, but as RADx and ACTIV exemplify, we’re making rapid progress through collaboration and a strong, sustained investment in scientific innovation.

Links:

Coronavirus (COVID-19) (NIH)

Rapid Acceleration of Diagnostics (RADx)

Video: NIH RADx Delivering New COVID-19 Testing Technologies to Meet U.S. Demand (YouTube)

Accelerating COVID-19 Therapeutic Interventions and Vaccines (ACTIV)

Explaining Operation Warp Speed (U.S. Department of Health and Human Resources/Washington, D.C.)

“NIH delivering new COVID-19 testing technologies to meet U.S. demand,” NIH news release,” July 31, 2020.

“NIH launches clinical trial to test antibody treatment in hospitalized COVID-19 patients,” NIH new release, August 4, 2020.

“NIH clinical trial to test antibodies and other experimental therapeutics for mild and moderate COVID-19,” NIH news release, August 4, 2020.

Share this:

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Telegram (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window)

- Click to print (Opens in new window)

Posted In: News

Tags: AbCellerra Biologics, Accelerating COVID-19 Therapeutic Interventions and Vaccines, ACTIV, antibodies, coronavirus, COVID-19, COVID-19 testing, COVID-19 treatment, diagnostics, Eli Lilly and Company, Fluidigm, Gingko Bioworks, Helix OpCo, lab-based testing, LY-CoV555, mAbs, Mammoth Biosciences, master protocols, Mesa Biotech, monoclonal antibody, novel coronavirus, Operation Warp Speed, pandemic, point-of-care tests, Quidel, RADx, Rapid Acceleration of Diagnostics Initiative, saliva test, SARS-CoV-2, spike protein, Talis Biomedical, therapeutics

Researchers Publish Encouraging Early Data on COVID-19 Vaccine

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

People all around the globe are anxiously awaiting development of a safe, effective vaccine to protect against the deadly threat of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Evidence is growing that biomedical research is on track to provide such help, and to do so in record time.

Just two days ago, in a paper in the New England Journal of Medicine [1], researchers presented encouraging results from the vaccine that’s furthest along in U.S. human testing: an innovative approach from NIH’s Vaccine Research Center (VRC), in partnership with Moderna Inc., Cambridge, MA [1]. The centerpiece of this vaccine is a small, non-infectious snippet of messenger RNA (mRNA). Injecting this mRNA into muscle will spur a person’s own body to make a key viral protein, which, in turn, will encourage the production of protective antibodies against SARS-CoV-2—the novel coronavirus that causes COVID-19.

While it generally takes five to 10 years to develop a vaccine against a new infectious agent, we simply don’t have that time with a pandemic as devastating as COVID-19. Upon learning of the COVID-19 outbreak in China early this year, and seeing the genome sequence of SARS-CoV-2 appear on the internet, researchers with NIH’s National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) carefully studied the viral instructions, focusing on the portion that codes for a spike protein that the virus uses to bind to and infect human cells.

Because of their experience with the original SARS virus back in the 2000s, they thought a similar approach to vaccine development would work and modified an existing design to reflect the different sequence of the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein. Literally within days, they had created a vaccine in the lab. They then went on to work with Moderna, a biotech firm that’s produced personalized cancer vaccines. All told, it took just 66 days from the time the genome sequence was made available in January to the start of the first-in-human study described in the new peer-reviewed paper.

In the NIH-supported phase 1 human clinical trial, researchers found the vaccine, called mRNA-1273, to be safe and generally well tolerated. Importantly, human volunteers also developed significant quantities of neutralizing antibodies that target the virus in the right place to block it from infecting their cells.

Conducted at Kaiser Permanente Washington Health Research Institute, Seattle; and Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, the trial led by Kaiser Permanente’s Lisa Jackson involved healthy adult volunteers. Each volunteer received two vaccinations in the upper arm at one of three doses, given approximately one month apart.

The volunteers will be tracked for a full year, allowing researchers to monitor their health and antibody production. However, the recently published paper provides interim data on the phase 1 trial’s first 45 participants, ages 18 to 55, for the first 57 days after their second vaccination. The data revealed:

• No volunteers suffered serious adverse events.

• Optimal dose to elicit high levels of neutralizing antibody activity, while also protecting patient safety, appears to be 100 micrograms. Doses administered in the phase 1 trial were either 25, 100, or 250 micrograms.

• More than half of the volunteers reported fatigue, headache, chills, muscle aches, or pain at the injection site. Those symptoms were most common after the second vaccination and in volunteers who received the highest vaccine dose. That dose will not be used in larger trials.

• Two doses of 100 micrograms of the vaccine prompted a robust immune response, which was last measured 43 days after the second dose. These responses were actually above the average levels seen in blood samples from people who had recovered from COVID-19.

These encouraging results are being used to inform the next rounds of human testing of the mRNA-1273 vaccine. A phase 2 clinical trial is already well on its way to recruiting 600 healthy adults.This study will continue to profile the vaccine’s safety, as well as its ability to trigger an immune response.

Meanwhile, later this month, a phase 3 clinical trial will begin enrolling 30,000 volunteers, with particular focus on recruitment in regions and populations that have been particularly hard hit by the virus.

The design of that trial, referred to as a “master protocol,” had major contributions from the Accelerating COVID-19 Therapeutic Interventions and Vaccine (ACTIV) initiative, a remarkable public-private partnership involving 20 biopharmaceutical companies, academic experts, and multiple federal agencies. Now, a coordinated effort across the U.S. government, called Operation Warp Speed, is supporting rapid conduct of these clinical trials and making sure that millions of doses of any successful vaccine will be ready if the vaccine proves save and effective.

Results of this first phase 3 trial are expected in a few months. If you are interested in volunteering for these or other prevention trials, please check out NIH’s new COVID-19 clinical trials network.

There’s still a lot of work that remains to be done, and anything can happen en route to the finish line. But by pulling together, and leaning on the very best science, I am confident that we will be able rise to the challenge of ending this pandemic that has devastated so many lives.

Reference:

[1] A SARS-CoV-2 mRNA Vaccine—Preliminary Report. Jackson LA, Anderson EJ, Rouphael NG, Ledgerwood JE, Graham BS, Beigel JH, et al. NEJM. 2020 July 14. [Publication ahead of print]

Links:

Coronavirus (COVID-19) (NIH)

Dale and Betty Bumpers Vaccine Research Center (National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases/NIH)

Moderna, Inc. (Cambridge, MA)

Safety and Immunogenicity Study of 2019-nCoV Vaccine (mRNA-1273) for Prophylaxis of SARS-CoV-2 Infection (COVID-19) (ClinicalTrials.gov)

“NIH Launches Clinical Trials Network to Test COVID-19 Vaccines and Other Prevention Tools,” NIAID News Release, NIH, July 8, 2020.

Accelerating COVID-19 Therapeutic Interventions and Vaccines (ACTIV) (NIH)

Explaining Operation Warp Speed (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Washington, DC)

NIH Support: National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases

Share this:

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Telegram (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window)

- Click to print (Opens in new window)

Posted In: News

Tags: Accelerating COVID-19 Therapeutic Interventions and Vaccines, ACTIV, antibodies, clinical trials, coronavirus, COVID-19, COVID-19 vaccine, COVPN, Kaiser Permanente, Moderna, mRNA, mRNA-1273, neutralizing antibodies, novel coronavirus, Operation Warp Speed, pandemic, SARS, SARS-CoV-2, spike protein, vaccine

Meet the Researcher Leading NIH’s COVID-19 Vaccine Development Efforts

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

A safe, effective vaccine is the ultimate tool needed to end the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. Biomedical researchers are making progress every day towards such a vaccine, whether it’s devising innovative technologies or figuring out ways to speed human testing. In fact, just this week, NIH’s National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) established a new clinical trials network that will enroll tens of thousands of volunteers in large-scale clinical trials testing a variety of investigational COVID-19 vaccines.

Among the vaccines moving rapidly through the development pipeline is one developed by NIAID’s Dale and Betty Bumpers Vaccine Research Center (VRC), in partnership with Moderna, Inc., Cambridge, MA. So, I couldn’t think of a better person to give us a quick overview of the COVID-19 vaccine research landscape than NIH’s Dr. John Mascola, who is Director of the VRC. Our recent conversation took place via videoconference, with John linking in from his home in Rockville, MD, and me from my place in nearby Chevy Chase. Here’s a condensed transcript of our chat:

Collins: Vaccines have been around since Edward Jenner and smallpox in the late 1700s. But how does a vaccine actually work to protect someone from infection?

Mascola: The immune system works by seeing something that’s foreign and then responding to it. Vaccines depend on the fact that if the immune system has seen a foreign protein or entity once, the second time the immune response will be much brisker. So, with these principles in mind, we vaccinate using part of a viral protein that the immune system will recognize as foreign. The response to this viral protein, or antigen, calls in specialized T and B cells, the so-called memory cells, and they remember the encounter. When you get exposed to the real thing, the immune system is already prepared. Its response is so rapid that you clear the virus before you get sick.

Collins: What are the steps involved in developing a vaccine?

Mascola: One can’t make a vaccine, generally speaking, without knowing something about the virus. We need to understand its surface proteins. We need to understand how the immune system sees the virus. Once that knowledge exists, we can make a candidate vaccine in the laboratory pretty quickly. We then transfer the vaccine to a manufacturing facility, called a pilot plant, that makes clinical grade material for testing. When enough testable material is available, we do a first-in-human study, often at our vaccine clinic at the NIH Clinical Center.

If those tests look promising, the next big step is finding a pharmaceutical partner to make the vaccine at large scale, seek regulatory approval, and distribute it commercially. That usually takes a while. So, from start to finish, the process often takes five or more years.

Collins: With this global crisis, we obviously don’t have five years to wait. Tell us about what the VRC started to do as soon as you learned about the outbreak in Wuhan, China.

Mascola: Sure. It’s a fascinating story. We had been talking with NIAID Director Dr. Anthony Fauci and our colleagues about how to prepare for the next pandemic. Pretty high on our list were coronaviruses, having already worked on past outbreaks of SARS and MERS [other respiratory diseases caused by coronaviruses]. So, we studied coronaviruses and focused on the unique spike protein crowning their surfaces. We designed a vaccine that presented the spike protein to the immune system.

Collins: Knowing that the spike protein was likely your antigen, what was your approach to designing the vaccine?

Mascola: Our approach was a nucleic acid-based vaccine. I’m referring to vaccines that are based on genetic material, either DNA or RNA. It’s this type of vaccine that can be moved most rapidly into the clinic for initial testing.

When we learned of the outbreak in Wuhan, we simply accessed the nucleic acid sequence of SARS-CoV-2, the novel coronavirus that causes COVID-19. Most of the sequence was on a server from Chinese investigators. We looked at the spike sequence and built that into an RNA vaccine. This is called in silico vaccine design. Because of our experience with the original SARS back in the 2000s, we knew its sequence and we knew this approach worked. We simply modified the vaccine design to the sequence of the spike protein of SARS-CoV-2. Literally within days, we started making the vaccine in the lab.

At the same time, we worked with a biotechnology company called Moderna that creates personalized cancer vaccines. From the time the sequence was made available in early January to the start of the first in-human study, it was about 65 days.

Collins: Wow! Has there ever been a vaccine developed in 65 days?

Mascola: I don’t think so. There are a lot of firsts with COVID, and vaccine development is one of them.

Collins: For the volunteers who enrolled in the phase 1 study, what was actually in the syringe?

Mascola: The syringe included messenger RNA (mRNA), the encoded instructions for making a specific protein, in this case the spike protein. The mRNA is formulated in a lipid nanoparticle shell. The reason is mRNA is less stable than DNA, and it doesn’t like to hang around in a test tube where enzymes can break it down. But if one formulates it just right into a nanoparticle, the mRNA is protected. Furthermore, that protective particle allows one to inject it into muscle and facilitates the uptake of the mRNA into the muscle cells. The cells translate the mRNA into spike proteins, and the immune system sees them and mounts a response.

Collins: Do muscle cells know how to take that protein and put it on their cell surfaces, where the immune system can see it?

Mascola: They do if the mRNA is engineered just the right way. We’ve been doing this with DNA for a long time. With mRNA, the advantage is that it just has to get into the cell [not into the nucleus of the cell as it does for DNA]. But it took about a decade of work to figure out how to do nucleotide silencing, which allows the cell to see the mRNA, not destroy it, and actually treat it as a normal piece of mRNA to translate into protein. Once that was figured out, it becomes pretty easy to make any specific vaccine.

Collins: That’s really an amazing part of the science. While it seems like this all happened in a blink of an eye, 65 days, it was built on years of basic science work to understand how cells treat mRNA. What’s the status of the vaccine right now?

Mascola: Early data from the phase 1 study are very encouraging. There’s a manuscript in preparation that should be out shortly showing that the vaccine was safe. It induced a very robust immune response to that spike protein. In particular, we looked for neutralizing antibodies, which are the ones that attach to the spike, blocking the virus from binding to a cell. There’s a general principle in vaccine development: if the immune system generates neutralizing antibodies, that’s a very good sign.

Collins: You’d be the first to say that you’re not done yet. Even though those are good signs, that doesn’t prove that this vaccine will work. What else do you need to know?

Mascola: The only real way to learn if a vaccine works is to test it in people. We break clinical studies into phases 1, 2, and 3. Phase 1 has already been done to evaluate safety. Phase 2 is a larger evaluation of safety and immune response. That’s ongoing and has enrolled 500 or 600 people, which is good. The plan for the phase 3 study will be to start in July. Again, that’s incredibly fast, considering that we didn’t even know this virus existed until January.

Collins: How many people do you need to study in a phase 3 trial?

Mascola: We’re thinking 20,000 or 30,000.

Collins: And half get the vaccine and half get a placebo?

Mascola: Sometimes it can be done differently, but the classic approach is half placebo, half vaccine.

Collins: We’ve been talking about the VRC-Moderna nucleic acid vaccine. But there are others that are coming along pretty quickly. What other strategies are being employed, and what are their timetables?

Mascola: There are many dozens of vaccines under development. The response has been extraordinary by academic groups, biotech companies, pharmaceutical companies, and NIH’s Accelerating COVID-19 Therapeutic Interventions and Vaccines (ACTIV) partnership. I don’t think I’ve ever seen so much activity in a vaccine space moving ahead at such a rapid clip.

As far as being ready for advanced clinical trials, there are a just handful and they involve different types of vaccines. At least three nucleic acid vaccines are in clinical trials. There are also two vaccines that use proteins, which is a more classic approach.

In addition, there are several vaccines based on a viral vector. To make these, one puts the genes for the spike protein inside an adenovirus, which is an innocuous cold virus, and injects it into muscle. In regard to phase 3 trials, there are maybe three or four vaccines that could be formally in such tests by the fall.

Collins: How is it possible to do this so much more rapidly than in the past, without imposing risks?

Mascola: It’s a really important question, Francis. A number of things are being done in parallel, and that wouldn’t usually be the case. We can get a vaccine into a first-in-human study much more quickly because of time-saving technologies.

But the real important point is that for the phase 3 trial, there are no timesavers. One must enroll 30,000 people and watch them over months in a very rigorous, placebo-controlled environment. The NIH has stood up what’s called a Data Safety Monitoring Board for all the trials. That’s an independent group of investigators that will review all vaccine trial data periodically. They can see what the data are showing: Should the trial be stopped early because the vaccine is working? Is there a safety signal that raises concern?

While the phase 3 trial is going on, the U.S. government also will be funding large-scale manufacture of the vaccine. Traditionally, you would do the vaccine trial, wait until it’s all done, and analyze the data. If it worked, you’d build a vaccine plant to make enough material, which takes two or three years, and then go to the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for regulatory approval.

Everything here is being done in parallel. So, if the vaccine works, it’s already in supply. And we have been engaging the FDA to get real-time feedback. That does save a lot of time.

Collins: Is it possible that we’ll manufacture a whole lot of doses that may have to be thrown out if the vaccine doesn’t work?