gene editing

Celebrating NIH Science, Blogs, and Blog Readers!

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Happy holidays to one and all! As you may have heard, this is my last holiday season as the Director of the National Institutes of Health (NIH)—a post that I’ve held for the past 12 years and four months under three U.S. Presidents. And, wow, it really does seem like only yesterday that I started this blog!

At the blog’s outset, I said my goal was to “highlight new discoveries in biology and medicine that I think are game changers, noteworthy, or just plain cool.” More than 1,100 posts, 10 million unique visitors, and 13.7 million views later, I hope you’ll agree that goal has been achieved. I’ve also found blogging to be a whole lot of fun, as well as a great way to expand my own horizons and share a little of what I’ve learned about biomedical advances with people all across the nation and around the world.

So, as I sign off as NIH Director and return to my lab at NIH’s National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI), I want to thank everyone who’s ever visited this Blog—from high school students to people with health concerns, from biomedical researchers to policymakers. I hope that the evidence-based information that I’ve provided has helped and informed my readers in some small way.

In this my final post, I’m sharing a short video (see above) that highlights just a few of the blog’s many spectacular images, many of them produced by NIH-funded scientists during the course of their research. In the video, you’ll see a somewhat quirky collection of entries, but hopefully you will sense my enthusiasm for the potential of biomedical research to fight human disease and improve human health—from innovative immunotherapies for treating cancer to the gift of mRNA vaccines to combat a pandemic.

Over the years, I’ve blogged about many of the bold, new frontiers of biomedicine that are now being explored by research teams supported by NIH. Who would have imagined that, within the span of a dozen years, precision medicine would go from being an interesting idea to a driving force behind the largest-ever NIH cohort seeking to individualize the prevention and treatment of common disease? Or that today we’d be deep into investigations of precisely how the human brain works, as well as how human health may benefit from some of the trillions of microbes that call our bodies home?

My posts also delved into some of the amazing technological advances that are enabling breakthroughs across a wide range of scientific fields. These innovative technologies include powerful new ways of mapping the atomic structures of proteins, editing genetic material, and designing improved gene therapies.

So, what’s next for NIH? Let me assure you that NIH is in very steady hands as it heads into a bright horizon brimming with exceptional opportunities for biomedical research. Like you, I look forward to discoveries that will lead us even closer to the life-saving answers that we all want and need.

While we wait for the President to identify a new NIH director, Lawrence Tabak, who has been NIH’s Principal Deputy Director and my right arm for the last decade, will serve as Acting NIH Director. So, keep an eye out for his first post in early January!

As for me, I’ll probably take a little time to catch up on some much-needed sleep, do some reading and writing, and hopefully get out for a few more rides on my Harley with my wife Diane. But there’s plenty of work to do in my lab, where the focus is on type 2 diabetes and a rare disease of premature aging called Hutchinson-Gilford Progeria Syndrome. I’m excited to pursue those research opportunities and see where they lead.

In closing, I’d like to extend my sincere thanks to each of you for your interest in hearing from the NIH Director—and supporting NIH research—over the past 12 years. It’s been an incredible honor to serve you at the helm of this great agency that’s often called the National Institutes of Hope. And now, for one last time, Diane and I take great pleasure in sending you and your loved ones our most heartfelt wishes for Happy Holidays and a Healthy New Year!

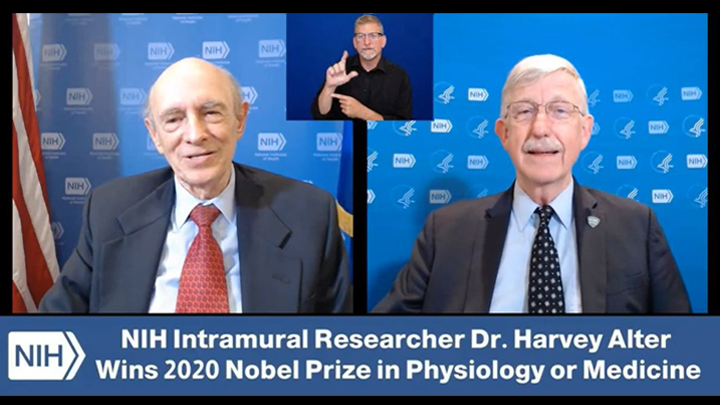

Engineering a Better Way to Deliver Therapeutic Genes to Muscles

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Amid all the progress toward ending the COVID-19 pandemic, it’s worth remembering that researchers here and around the world continue to make important advances in tackling many other serious health conditions. As an inspiring NIH-supported example, I’d like to share an advance on the use of gene therapy for treating genetic diseases that progressively degenerate muscle, such as Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD).

As published recently in the journal Cell, researchers have developed a promising approach to deliver therapeutic genes and gene editing tools to muscle more efficiently, thus requiring lower doses [1]. In animal studies, the new approach has targeted muscle far more effectively than existing strategies. It offers an exciting way forward to reduce unwanted side effects from off-target delivery, which has hampered the development of gene therapy for many conditions.

In boys born with DMD (it’s an X-linked disease and therefore affects males), skeletal and heart muscles progressively weaken due to mutations in a gene encoding a critical muscle protein called dystrophin. By age 10, most boys require a wheelchair. Sadly, their life expectancy remains less than 30 years.

The hope is gene therapies will one day treat or even cure DMD and allow people with the disease to live longer, high-quality lives. Unfortunately, the benign adeno-associated viruses (AAVs) traditionally used to deliver the healthy intact dystrophin gene into cells mostly end up in the liver—not in muscles. It’s also the case for gene therapy of many other muscle-wasting genetic diseases.

The heavy dose of viral vector to the liver is not without concern. Recently and tragically, there have been deaths in a high-dose AAV gene therapy trial for X-linked myotubular myopathy (XLMTM), a different disorder of skeletal muscle in which there may already be underlying liver disease, potentially increasing susceptibility to toxicity.

To correct this concerning routing error, researchers led by Mohammadsharif Tabebordbar in the lab of Pardis Sabeti, Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard and Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, have now assembled an optimized collection of AAVs. They have been refined to be about 10 times better at reaching muscle fibers than those now used in laboratory studies and clinical trials. In fact, researchers call them myotube AAVs, or MyoAAVs.

MyoAAVs can deliver therapeutic genes to muscle at much lower doses—up to 250 times lower than what’s needed with traditional AAVs. While this approach hasn’t yet been tried in people, animal studies show that MyoAAVs also largely avoid the liver, raising the prospect for more effective gene therapies without the risk of liver damage and other serious side effects.

In the Cell paper, the researchers demonstrate how they generated MyoAAVs, starting out with the commonly used AAV9. Their goal was to modify the outer protein shell, or capsid, to create an AAV that would be much better at specifically targeting muscle. To do so, they turned to their capsid engineering platform known as, appropriately enough, DELIVER. It’s short for Directed Evolution of AAV capsids Leveraging In Vivo Expression of transgene RNA.

Here’s how DELIVER works. The researchers generate millions of different AAV capsids by adding random strings of amino acids to the portion of the AAV9 capsid that binds to cells. They inject those modified AAVs into mice and then sequence the RNA from cells in muscle tissue throughout the body. The researchers want to identify AAVs that not only enter muscle cells but that also successfully deliver therapeutic genes into the nucleus to compensate for the damaged version of the gene.

This search delivered not just one AAV—it produced several related ones, all bearing a unique surface structure that enabled them specifically to target muscle cells. Then, in collaboration with Amy Wagers, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, the team tested their MyoAAV toolset in animal studies.

The first cargo, however, wasn’t a gene. It was the gene-editing system CRISPR-Cas9. The team found the MyoAAVs correctly delivered the gene-editing system to muscle cells and also repaired dysfunctional copies of the dystrophin gene better than the CRISPR cargo carried by conventional AAVs. Importantly, the muscles of MyoAAV-treated animals also showed greater strength and function.

Next, the researchers teamed up with Alan Beggs, Boston Children’s Hospital, and found that MyoAAV was effective in treating mouse models of XLMTM. This is the very condition mentioned above, in which very high dose gene therapy with a current AAV vector has led to tragic outcomes. XLMTM mice normally die in 10 weeks. But, after receiving MyoAAV carrying a corrective gene, all six mice had a normal lifespan. By comparison, mice treated in the same way with traditional AAV lived only up to 21 weeks of age. What’s more, the researchers used MyoAAV at a dose 100 times lower than that currently used in clinical trials.

While further study is needed before this approach can be tested in people, MyoAAV was also used to successfully introduce therapeutic genes into human cells in the lab. This suggests that the early success in animals might hold up in people. The approach also has promise for developing AAVs with potential for targeting other organs, thereby possibly providing treatment for a wide range of genetic conditions.

The new findings are the result of a decade of work from Tabebordbar, the study’s first author. His tireless work is also personal. His father has a rare genetic muscle disease that has put him in a wheelchair. With this latest advance, the hope is that the next generation of promising gene therapies might soon make its way to the clinic to help Tabebordbar’s father and so many other people.

Reference:

[1] Directed evolution of a family of AAV capsid variants enabling potent muscle-directed gene delivery across species. Tabebordbar M, Lagerborg KA, Stanton A, King EM, Ye S, Tellez L, Krunnfusz A, Tavakoli S, Widrick JJ, Messemer KA, Troiano EC, Moghadaszadeh B, Peacker BL, Leacock KA, Horwitz N, Beggs AH, Wagers AJ, Sabeti PC. Cell. 2021 Sep 4:S0092-8674(21)01002-3.

Links:

Muscular Dystrophy Information Page (National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke/NIH)

X-linked myotubular myopathy (Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center/National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences/NIH)

Somatic Cell Genome Editing (Common Fund/NIH)

Mohammadsharif Tabebordbar (Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard and Harvard University, Cambridge, MA)

Sabeti Lab (Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard and Harvard University)

NIH Support: Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development; Common Fund

Could CRISPR Gene-Editing Technology Be an Answer to Chronic Pain?

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Gene editing has shown great promise as a non-heritable way to treat a wide range of conditions, including many genetic diseases and more recently, even COVID-19. But could a version of the CRISPR gene-editing tool also help deliver long-lasting pain relief without the risk of addiction associated with prescription opioid drugs?

In work recently published in the journal Science Translational Medicine, researchers demonstrated in mice that a modified version of the CRISPR system can be used to “turn off” a gene in critical neurons to block the transmission of pain signals [1]. While much more study is needed and the approach is still far from being tested in people, the findings suggest that this new CRISPR-based strategy could form the basis for a whole new way to manage chronic pain.

This novel approach to treating chronic pain occurred to Ana Moreno, the study’s first author, when she was a Ph.D. student in the NIH-supported lab of Prashant Mali, University of California, San Diego. Mali had been studying a wide range of novel gene- and cell-based therapeutics. While reading up on both, Moreno landed on a paper about a mutation in a gene that encodes a pain-enhancing protein in spinal neurons called NaV1.7.

Moreno read that kids born with a loss-of-function mutation in this gene have a rare condition known as congenital insensitivity to pain (CIP). They literally don’t sense and respond to pain. Although these children often fail to recognize serious injuries because of the absence of pain to alert them, they have no other noticeable physical effects of the condition.

For Moreno, something clicked. What if it were possible to engineer a new kind of treatment—one designed to turn this gene down or fully off and stop people from feeling chronic pain?

Moreno also had an idea about how to do it. She’d been working on repressing or “turning off” genes using a version of CRISPR known as “dead” Cas9 [2]. In CRISPR systems designed to edit DNA, the Cas9 enzyme is often likened to a pair of scissors. Its job is to cut DNA in just the right spot with the help of an RNA guide. However, CRISPR-dead Cas9 no longer has any ability to cut DNA. It simply sticks to its gene target and blocks its expression. Another advantage is that the system won’t lead to any permanent DNA changes, since any treatment based on CRISPR-dead Cas9 might be safely reversed.

After establishing that the technique worked in cells, Moreno and colleagues moved to studies of laboratory mice. They injected viral vectors carrying the CRISPR treatment into mice with different types of chronic pain, including inflammatory and chemotherapy-induced pain.

Moreno and colleagues determined that all the mice showed evidence of durable pain relief. Remarkably, the treatment also lasted for three months or more and, importantly, without any signs of side effects. The researchers are also exploring another approach to do the same thing using a different set of editing tools called zinc finger nucleases (ZFNs).

The researchers say that one of these approaches might one day work for people with a large number of chronic pain conditions that involve transmission of the pain signal through NaV1.7. That includes diabetic polyneuropathy, sciatica, and osteoarthritis. It also could provide relief for patients undergoing chemotherapy, along with those suffering from many other conditions. Moreno and Mali have co-founded the spinoff company Navega Therapeutics, San Diego, CA, to work on the preclinical steps necessary to help move their approach closer to the clinic.

Chronic pain is a devastating public health problem. While opioids are effective for acute pain, they can do more harm than good for many chronic pain conditions, and they are responsible for a nationwide crisis of addiction and drug overdose deaths [3]. We cannot solve any of these problems without finding new ways to treat chronic pain. As we look to the future, it’s hopeful that innovative new therapeutics such as this gene-editing system could one day help to bring much needed relief.

References:

[1] Long-lasting analgesia via targeted in situ repression of NaV1.7 in mice. Moreno AM, Alemán F, Catroli GF, Hunt M, Hu M, Dailamy A, Pla A, Woller SA, Palmer N, Parekh U, McDonald D, Roberts AJ, Goodwill V, Dryden I, Hevner RF, Delay L, Gonçalves Dos Santos G, Yaksh TL, Mali P. Sci Transl Med. 2021 Mar 10;13(584):eaay9056.

[2] Nuclease dead Cas9 is a programmable roadblock for DNA replication. Whinn KS, Kaur G, Lewis JS, Schauer GD, Mueller SH, Jergic S, Maynard H, Gan ZY, Naganbabu M, Bruchez MP, O’Donnell ME, Dixon NE, van Oijen AM, Ghodke H. Sci Rep. 2019 Sep 16;9(1):13292.

[3] Drug Overdose Deaths. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Links:

Congenital insensitivity to pain (National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences/NIH)

Opioids (National Institute on Drug Abuse/NIH)

Mali Lab (University of California, San Diego)

Navega Therapeutics (San Diego, CA)

NIH Support: National Human Genome Research Institute; National Cancer Institute; National Institute of General Medical Sciences; National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke

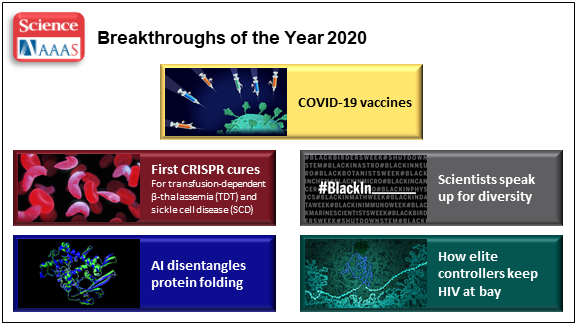

What A Year It Was for Science Advances!

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

At the close of every year, editors and writers at the journal Science review the progress that’s been made in all fields of science—from anthropology to zoology—to select the biggest advance of the past 12 months. In most cases, this Breakthrough of the Year is as tough to predict as the Oscar for Best Picture. Not in 2020. In a year filled with a multitude of challenges posed by the emergence of the deadly coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-2019), the breakthrough was the development of the first vaccines to protect against this pandemic that’s already claimed the lives of more than 360,000 Americans.

In keeping with its annual tradition, Science also selected nine runner-up breakthroughs. This impressive list includes at least three areas that involved efforts supported by NIH: therapeutic applications of gene editing, basic research understanding HIV, and scientists speaking up for diversity. Here’s a quick rundown of all the pioneering advances in biomedical research, both NIH and non-NIH funded:

Shots of Hope. A lot of things happened in 2020 that were unprecedented. At the top of the list was the rapid development of COVID-19 vaccines. Public and private researchers accomplished in 10 months what normally takes about 8 years to produce two vaccines for public use, with more on the way in 2021. In my more than 25 years at NIH, I’ve never encountered such a willingness among researchers to set aside their other concerns and gather around the same table to get the job done fast, safely, and efficiently for the world.

It’s also pretty amazing that the first two conditionally approved vaccines from Pfizer and Moderna were found to be more than 90 percent effective at protecting people from infection with SARS-CoV-2, the coronavirus that causes COVID-19. Both are innovative messenger RNA (mRNA) vaccines, a new approach to vaccination.

For this type of vaccine, the centerpiece is a small, non-infectious snippet of mRNA that encodes the instructions to make the spike protein that crowns the outer surface of SARS-CoV-2. When the mRNA is injected into a shoulder muscle, cells there will follow the encoded instructions and temporarily make copies of this signature viral protein. As the immune system detects these copies, it spurs the production of antibodies and helps the body remember how to fend off SARS-CoV-2 should the real thing be encountered.

It also can’t be understated that both mRNA vaccines—one developed by Pfizer and the other by Moderna in conjunction with NIH’s National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases—were rigorously evaluated in clinical trials. Detailed data were posted online and discussed in all-day meetings of an FDA Advisory Committee, open to the public. In fact, given the high stakes, the level of review probably was more scientifically rigorous than ever.

First CRISPR Cures: One of the most promising areas of research now underway involves gene editing. These tools, still relatively new, hold the potential to fix gene misspellings—and potentially cure—a wide range of genetic diseases that were once to be out of reach. Much of the research focus has centered on CRISPR/Cas9. This highly precise gene-editing system relies on guide RNA molecules to direct a scissor-like Cas9 enzyme to just the right spot in the genome to cut out or correct a disease-causing misspelling.

In late 2020, a team of researchers in the United States and Europe succeeded for the first time in using CRISPR to treat 10 people with sickle cell disease and transfusion-dependent beta thalassemia. As published in the New England Journal of Medicine, several months after this non-heritable treatment, all patients no longer needed frequent blood transfusions and are living pain free [1].

The researchers tested a one-time treatment in which they removed bone marrow from each patient, modified the blood-forming hematopoietic stem cells outside the body using CRISPR, and then reinfused them into the body. To prepare for receiving the corrected cells, patients were given toxic bone marrow ablation therapy, in order to make room for the corrected cells. The result: the modified stem cells were reprogrammed to switch back to making ample amounts of a healthy form of hemoglobin that their bodies produced in the womb. While the treatment is still risky, complex, and prohibitively expensive, this work is an impressive start for more breakthroughs to come using gene editing technologies. NIH, including its Somatic Cell Genome Editing program, continues to push the technology to accelerate progress and make gene editing cures for many disorders simpler and less toxic.

Scientists Speak Up for Diversity: The year 2020 will be remembered not only for COVID-19, but also for the very public and inescapable evidence of the persistence of racial discrimination in the United States. Triggered by the killing of George Floyd and other similar events, Americans were forced to come to grips with the fact that our society does not provide equal opportunity and justice for all. And that applies to the scientific community as well.

Science thrives in safe, diverse, and inclusive research environments. It suffers when racism and bigotry find a home to stifle diversity—and community for all—in the sciences. For the nation’s leading science institutions, there is a place and a calling to encourage diversity in the scientific workplace and provide the resources to let it flourish to everyone’s benefit.

For those of us at NIH, last year’s peaceful protests and hashtags were noticed and taken to heart. That’s one of the many reasons why we will continue to strengthen our commitment to building a culturally diverse, inclusive workplace. For example, we have established the NIH Equity Committee. It allows for the systematic tracking and evaluation of diversity and inclusion metrics for the intramural research program for each NIH institute and center. There is also the recently founded Distinguished Scholars Program, which aims to increase the diversity of tenure track investigators at NIH. Recently, NIH also announced that it will provide support to institutions to recruit diverse groups or “cohorts” of early-stage research faculty and prepare them to thrive as NIH-funded researchers.

AI Disentangles Protein Folding: Proteins, which are the workhorses of the cell, are made up of long, interconnected strings of amino acids that fold into a wide variety of 3D shapes. Understanding the precise shape of a protein facilitates efforts to figure out its function, its potential role in a disease, and even how to target it with therapies. To gain such understanding, researchers often try to predict a protein’s precise 3D chemical structure using basic principles of physics—including quantum mechanics. But while nature does this in real time zillions of times a day, computational approaches have not been able to do this—until now.

Of the roughly 170,000 proteins mapped so far, most have had their structures deciphered using powerful imaging techniques such as x-ray crystallography and cryo–electron microscopy (cryo-EM). But researchers estimate that there are at least 200 million proteins in nature, and, as amazing as these imaging techniques are, they are laborious, and it can take many months or years to solve 3D structure of a single protein. So, a breakthrough certainly was needed!

In 2020, researchers with the company Deep Mind, London, developed an artificial intelligence (AI) program that rapidly predicts most protein structures as accurately as x-ray crystallography and cryo-EM can map them [2]. The AI program, called AlphaFold, predicts a protein’s structure by computationally modeling the amino acid interactions that govern its 3D shape.

Getting there wasn’t easy. While a complete de novo calculation of protein structure still seemed out of reach, investigators reasoned that they could kick start the modeling if known structures were provided as a training set to the AI program. Utilizing a computer network built around 128 machine learning processors, the AlphaFold system was created by first focusing on the 170,000 proteins with known structures in a reiterative process called deep learning. The process, which is inspired by the way neural networks in the human brain process information, enables computers to look for patterns in large collections of data. In this case, AlphaFold learned to predict the underlying physical structure of a protein within a matter of days. This breakthrough has the potential to accelerate the fields of structural biology and protein research, fueling progress throughout the sciences.

How Elite Controllers Keep HIV at Bay: The term “elite controller” might make some people think of video game whizzes. But here, it refers to the less than 1 percent of people living with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) who’ve somehow stayed healthy for years without taking antiretroviral drugs. In 2020, a team of NIH-supported researchers figured out why this is so.

In a study of 64 elite controllers, published in the journal Nature, the team discovered a link between their good health and where the virus has inserted itself in their genomes [3]. When a cell transcribes a gene where HIV has settled, this so-called “provirus,” can produce more virus to infect other cells. But if it settles in a part of a chromosome that rarely gets transcribed, sometimes called a gene desert, the provirus is stuck with no way to replicate. Although this discovery won’t cure HIV/AIDS, it points to a new direction for developing better treatment strategies.

In closing, 2020 presented more than its share of personal and social challenges. Among those challenges was a flood of misinformation about COVID-19 that confused and divided many communities and even families. That’s why the editors and writers at Science singled out “a second pandemic of misinformation” as its Breakdown of the Year. This divisiveness should concern all of us greatly, as COVID-19 cases continue to soar around the country and our healthcare gets stretched to the breaking point. I hope and pray that we will all find a way to come together, both in science and in society, as we move forward in 2021.

References:

[1] CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing for sickle cell disease and β-thalassemia. Frangoul H et al. N Engl J Med. 2020 Dec 5.

[2] ‘The game has changed.’ AI triumphs at protein folding. Service RF. Science. 04 Dec 2020.

[3] Distinct viral reservoirs in individuals with spontaneous control of HIV-1. Jiang C et al. Nature. 2020 Sep;585(7824):261-267.

Links:

COVID-19 Research (NIH)

2020 Science Breakthrough of the Year (American Association for the Advancement of Science, Washington, D.C)

DNA Base Editing May Treat Progeria, Study in Mice Shows

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

My good friend Sam Berns was born with a rare genetic condition that causes rapid premature aging. Though Sam passed away in his teens from complications of this condition, called Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome, he’s remembered today for his truly positive outlook on life. Sam expressed it, in part, by his willingness to make adjustments that allowed him, in his words, to put things that he always wanted to do in the “can do” category.

In this same spirit on behalf of the several hundred kids worldwide with progeria and their families, a research collaboration, including my NIH lab, has now achieved a key technical advance to move non-heritable gene editing another step closer to the “can do” category to treat progeria. As published in the journal Nature, our team took advantage of new gene-editing tools to correct for the first time a single genetic misspelling responsible for progeria in a mouse model, with dramatically beneficial effects [1, 2]. This work also has implications for correcting similar single-base typos that cause other inherited genetic disorders.

The outcome of this work is incredibly gratifying for me. In 2003, my NIH lab discovered the DNA mutation that causes progeria. One seemingly small glitch—swapping a “T” in place of a “C” in a gene called lamin A (LMNA)—leads to the production of a toxic protein now known as progerin. Without treatment, children with progeria develop normally intellectually but age at an exceedingly rapid pace, usually dying prematurely from heart attacks or strokes in their early teens.

The discovery raised the possibility that correcting this single-letter typo might one day help or even cure children with progeria. But back then, we lacked the needed tools to edit DNA safely and precisely. To be honest, I didn’t think that would be possible in my lifetime. Now, thanks to advances in basic genomic research, including work that led to the 2020 Nobel Prize in Chemistry, that’s changed. In fact, there’s been substantial progress toward using gene-editing technologies, such as the CRISPR editing system, for treating or even curing a wide range of devastating genetic conditions, such as sickle cell disease and muscular dystrophy

It turns out that the original CRISPR system, as powerful as it is, works better at knocking out genes than correcting them. That’s what makes some more recently developed DNA editing agents and approaches so important. One of them, which was developed by David R. Liu, Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard, Cambridge, MA, and his lab members, is key to these latest findings on progeria, reported by a team including my lab in NIH’s National Human Genome Research Institute and Jonathan Brown, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, TN.

The relatively new gene-editing system moves beyond knock-outs to knock-ins [3,4]. Here’s how it works: Instead of cutting DNA as CRISPR does, base editors directly convert one DNA letter to another by enzymatically changing one DNA base to become a different base. The result is much like the find-and-replace function used to fix a typo in a word processor. What’s more, the gene editor does this without cutting the DNA.

Our three labs (Liu, Brown, and Collins) first teamed up with the Progeria Research Foundation, Peabody, MA, to obtain skin cells from kids with progeria. In lab studies, we found that base editors, targeted by an appropriate RNA guide, could successfully correct the LMNA gene in those connective tissue cells. The treatment converted the mutation back to the normal gene sequence in an impressive 90 percent of the cells.

But would it work in a living animal? To get the answer, we delivered a single injection of the DNA-editing apparatus into nearly a dozen mice either three or 14 days after birth, which corresponds in maturation level roughly to a 1-year-old or 5-year-old human. To ensure the findings in mice would be as relevant as possible to a future treatment for use in humans, we took advantage of a mouse model of progeria developed in my NIH lab in which the mice carry two copies of the human LMNA gene variant that causes the condition. Those mice develop nearly all of the features of the human illness

In the live mice, the base-editing treatment successfully edited in the gene’s healthy DNA sequence in 20 to 60 percent of cells across many organs. Many cell types maintained the corrected DNA sequence for at least six months—in fact, the most vulnerable cells in large arteries actually showed an almost 100 percent correction at 6 months, apparently because the corrected cells had compensated for the uncorrected cells that had died out. What’s more, the lifespan of the treated animals increased from seven to almost 18 months. In healthy mice, that’s approximately the beginning of old age.

This is the second notable advance in therapeutics for progeria in just three months. Last November, based on preclinical work from my lab and clinical trials conducted by the Progeria Research Foundation in Boston, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the first treatment for the condition. It is a drug called Zokinvy, and works by reducing the accumulation of progerin [5]. With long-term treatment, the drug is capable of extending the life of kids with progeria by 2.5 years and sometimes more. But it is not a cure.

We are hopeful this gene editing work might eventually lead to a cure for progeria. But mice certainly aren’t humans, and there are still important steps that need to be completed before such a gene-editing treatment could be tried safely in people. In the meantime, base editors and other gene editing approaches keep getting better—with potential application to thousands of genetic diseases where we know the exact gene misspelling. As we look ahead to 2021, the dream envisioned all those years ago about fixing the tiny DNA typo responsible for progeria is now within our grasp and getting closer to landing in the “can do” category.

References:

[1] In vivo base editing rescues Hutchinson-Gilford Progeria Syndrome in mice. Koblan LW et al. Nature. 2021 Jan 6.

[2] Base editor repairs mutation found in the premature-ageing syndrome progeria. Vermeij WP, Hoeijmakers JHJ. Nature. 6 Jan 2021.

[3] Programmable editing of a target base in genomic DNA without double-stranded DNA cleavage. Komor AC, Kim YB, Packer MS, Zuris JA, Liu DR. Nature. 2016 May 19;533(7603):420-424.

[4] Programmable base editing of A•T to G•C in genomic DNA without DNA cleavage. Gaudelli NM, Komor AC, Rees HA, Packer MS, Badran AH, Bryson DI, Liu DR. Nature. 2017 Nov 23;551(7681):464-471.

[5] FDA approves first treatment for Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome and some progeroid laminopathies. Food and Drug Administration. 2020 Nov 20.

Links:

Progeria (Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center/NIH)

What are Genome Editing and CRISPR-Cas9? (National Library of Medicine/NIH)

Somatic Cell Genome Editing Program (Common Fund/NIH)

David R. Liu (Harvard University, Cambridge, MA)

Collins Group (National Human Genome Research Institute/NIH)

Jonathan Brown (Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, TN)

NIH Support: National Human Genome Research Institute; National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences; National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering; National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases; National Institute of General Medical Sciences; Common Fund

Experts Conclude Heritable Human Genome Editing Not Ready for Clinical Applications

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

We stand at a critical juncture in the history of science. CRISPR and other innovative genome editing systems have given researchers the ability to make very precise changes in the sequence, or spelling, of the human DNA instruction book. If these tools are used to make non-heritable edits in only relevant tissues, they hold enormous potential to treat or even cure a wide range of devastating disorders, such as sickle cell disease, inherited neurologic conditions, and muscular dystrophy. But profound safety, ethical, and philosophical concerns surround the use of such technologies to make heritable changes in the human genome—changes that can be passed on to offspring and have consequences for future generations of humankind.

Such concerns are not hypothetical. Two years ago, a researcher in China took it upon himself to cross this ethical red line and conduct heritable genome editing experiments in human embryos with the aim of protecting the resulting babies against HIV infection. The medical justification was indefensible, the safety issues were inadequately considered, and the consent process was woefully inadequate. In response to this epic scientific calamity, NIH supported a call by prominent scientists for an international moratorium on human heritable, or germline, genome editing for clinical purposes.

Following on the heels of this unprecedented ethical breach, the U.S. National Academy of Sciences, U.S. National Academy of Medicine, and the U.K. Royal Society convened an international commission, sponsored by NIH, to conduct a comprehensive review of the clinical use of human germline genome editing. The 18-member panel, which represented 10 nations and four continents, included experts in genome editing technology; human genetics and genomics; psychology; reproductive, pediatric, and adult medicine; regulatory science; bioethics; and international law. Earlier this month, this commission issued its consensus study report, entitled Heritable Human Genome Editing [1].

The commission was designed to bring together thought leaders around the globe to engage in serious discussions about this highly controversial use of genome-editing technology. Among the concerns expressed by many of us was that if heritable genome editing were allowed to proceed without careful deliberation, the enormous potential of non-heritable genome editing for prevention and treatment of disease could become overshadowed by justifiable public outrage, fear, and disgust.

I’m gratified to say that in its new report, the expert panel closely examined the scientific and ethical issues, and concluded that heritable human genome editing is too technologically unreliable and unsafe to risk testing it for any clinical application in humans at the present time. The report cited the potential for unintended off-target DNA edits, which could have harmful health effects, such as cancer, later in life. Also noted was the risk of producing so-called mosaic embryos, in which the edits occur in only a subset of an embryo’s cells. This would make it very difficult for researchers to predict the clinical effects of heritable genome editing in human beings.

Among the many questions that the panel was asked to consider was: should society ever decide that heritable gene editing might be acceptable, what would be a viable framework for scientists, clinicians, and regulatory authorities to assess the potential clinical applications?

In response to that question, the experts replied: heritable gene editing, if ever permitted, should be limited initially to serious diseases that result from the mutation of one or both copies of a single gene. The first uses of these technologies should proceed incrementally and with extreme caution. Their potential medical benefits and harms should also be carefully evaluated before proceeding.

The commission went on to stress that before such an option could be on the table, all other viable reproductive possibilities to produce an embryo without a disease-causing alteration must be exhausted. That would essentially limit heritable gene editing to the exceedingly rare instance in which both parents have two copies of a recessive, disease-causing gene variant. Or another quite rare instance in which one parent has two copies of an altered gene for a dominant genetic disorder, such as Huntington’s disease.

Recognizing how unusual both scenarios would be, the commission held out the possibility that some would-be parents with less serious conditions might qualify if 25 percent or less of their embryos are free of the disease-causing gene variant. A possible example is familial hypercholesterolemia (FH), in which people carrying a mutation in the LDL receptor gene have unusually high levels of cholesterol in their blood. If both members of a couple are affected, only 25 percent of their biological children would be unaffected. FH can lead to early heart disease and death, but drug treatment is available and improving all the time, which makes this a less compelling example. Also, the commission again indicated that such individuals would need to have already traveled down all other possible reproductive avenues before considering heritable gene editing.

A thorny ethical question that was only briefly addressed in the commission’s report is the overall value to be attached to a couple’s desire to have a biological child. That desire is certainly understandable, although other options, such an adoption or in vitro fertilization with donor sperm, are available. This seems like a classic example of the tension between individual desires and societal concerns. Is the drive for a biological child in very high-risk situations such a compelling circumstance that it justifies asking society to start down a path towards modifying human germline DNA?

The commission recommended establishing an international scientific advisory board to monitor the rapidly evolving state of genome editing technologies. The board would serve as an access point for scientists, legislators, and the public to access credible information to weigh the latest progress against the concerns associated with clinical use of heritable human genome editing.

The National Academies/Royal Society report has been sent along to the World Health Organization (WHO), where it will serve as a resource for its expert advisory committee on human genome editing. The WHO committee is currently developing recommendations for appropriate governance mechanisms for both heritable and non-heritable human genome editing research and their clinical uses. That panel could issue its guidance later this year, which is sure to continue this very important conversation.

Reference:

[1] Heritable Human Genome Editing, Report Summary, National Academy of Sciences, September 2020.

Links:

“Heritable Genome Editing Not Yet Ready to Be Tried Safely and Effectively in Humans,” National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine news release, Sep. 3, 2020.

International Commission on the Clinical Use of Human Germline Genome Editing (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine/Washington, D.C.)

Video: Report Release Webinar , International Commission on the Clinical Use of Human Germline Genome Editing (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine)

National Academy of Sciences (Washington, D.C.)

National Academy of Medicine (Washington, D.C.)

The Royal Society (London)

Study Suggests Repurposed Drugs Might Treat Aggressive Lung Cancer

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Credit: Leanne Li, Koch Institute at MIT

Despite continued progress in treatment and prevention, lung cancer remains our nation’s leading cause of cancer death. In fact, more Americans die of lung cancer each year than of breast, colon, and prostate cancers combined [1,2]. While cigarette smoking is a major cause, lung cancer also occurs in non-smokers. I’m pleased to report discovery of what we hope will be a much-needed drug target for a highly aggressive, difficult-to-treat form of the disease, called small cell lung cancer (SCLC).

Using gene-editing technology to conduct a systematic, large-scale search for druggable vulnerabilities in certain types of cancer cells grown in lab dishes, NIH-funded researchers recently identified a metabolic pathway that appears to play a key role in SCLC. What makes this news even more encouraging is drugs that block this pathway already exist. That includes one in clinical testing for other types of cancer, and another that’s FDA-approved and has been safely used for more than 20 years to treat people with rheumatoid arthritis.

The new work comes from the lab of Tyler Jacks, Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), Cambridge. The Jacks lab, which is dedicated to understanding the genetic events that lead to cancer, develops mouse models engineered to carry the same genetic mutations that turn up in human cancers.

In work described in Science Translational Medicine, the team, co-led by Leanne Li and Sheng Rong Ng, applied CRISPR gene-editing tools to cells grown from some of their mouse models. Aiming high in terms of scale, researchers used CRISPR to knock out systematically, one by one, each of about 5,000 genes in cells from the SCLC mouse model, as well in cells from mouse models of other types of lung and pancreatic cancers. They looked to see what gene knockouts would slow down or kill the cancer cells, because that would be a good indication that the protein products of these genes, or the pathways they mediated, would be potential drug targets.

Out of those thousands of genes, one rose to the top of the list. It encodes an enzyme called DHODH (dihydroorotate dehydrogenase). This enzyme plays an important role in synthesizing pyrimidine, which is a major building block in DNA and RNA. Cytosine and thymine, the C and T in the four-letter DNA code, are pyrimidines; so is uracil, the U in RNA that takes the place of T in DNA. Because cancer cells are constantly dividing, there is a continual need to synthesize new DNA and RNA molecules to support the production of new daughter cells. And that means, unlike healthy cells, cancer cells require a steady supply of pyrimidine.

It turns out that the SCLC cells have an unexpected weakness relative to other cancer cells: they don’t produce as much pyrimidine. As a result, the researchers found blocking DHODH left the cells short on pyrimidine, leading to reduced growth and survival of the cancer.

This was especially good news because DHODH-blocking drugs, including one called brequinar, have already been tested in clinical trials for other cancers. In fact, brequinar is now being explored as a potential treatment for acute myeloid leukemia.

Might brequinar also hold promise for treating SCLC? To explore further, the researchers looked again to their genetic mouse model of SCLC. Their studies showed that mice treated with brequinar lived about 40 days longer than control animals. That’s a significant survival benefit in this system.

Brequinar treatment appeared to work even better when combined with other approved cancer drugs in mice that had SCLC cells transplanted into them. Further study in mice carrying SCLC tumors derived from four human patients added to this evidence. Two of the four human tumors shrunk in mice treated with brequinar.

Of course, mice are not people. But the findings suggest that brequinar or another DHODH blocker might hold promise as a new way to treat SCLC. While more study is needed to understand even better how brequinar works and explore potentially promising drug combinations, the fact that this drug is already in human testing for another indication suggests that a clinical trial to explore its use for SCLC might happen more quickly.

More broadly, the new findings show the promise of gene-editing technology as a research tool for uncovering elusive cancer targets. Such hard-fought discoveries will help to advance precise approaches to the treatment of even the most aggressive cancer types. And that should come as encouraging news to all those who are hoping to find new answers for hard-to-treat cancers.

References:

[1] Cancer Stat Facts: Lung and Bronchus Cancer (National Cancer Institute/NIH)

[2] Key Statistics for Lung Cancer (American Cancer Society)

[3] Identification of DHODH as a therapeutic target in small cell lung cancer. Li L, Ng SR, Colón CI, Drapkin BJ, Hsu PP, Li Z, Nabel CS, Lewis CA, Romero R, Mercer KL, Bhutkar A, Phat S, Myers DT, Muzumdar MD, Westcott PMK, Beytagh MC, Farago AF, Vander Heiden MG, Dyson NJ, Jacks T. Sci Transl Med. 2019 Nov 6;11(517).

Links:

Small Cell Lung Cancer Treatment (NCI/NIH)

Video: Introduction to Genome Editing Using CRISPR Cas9 (NIH)

Tyler Jacks (Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge)

NIH Support: National Cancer Institute

Next Page