pain

Pain Circuit Discovery in the Brain Suggests Promising Alternative to Opioid Painkillers

Posted on by Lawrence Tabak, D.D.S., Ph.D.

Chronic pain is an often-debilitating health condition and serious public health concern, affecting more than 50 million Americans.1 The opioid and overdose crisis, which stems from inadequate pain treatment, continues to have a devastating impact on families and communities across the country. To combat both challenges, we urgently need new ways to treat acute and chronic pain effectively without the many downsides of opioids.

While there are already multiple classes of non-opioid pain medications and other approaches to manage pain, unfortunately none have proved as effective as opioids when it comes to pain relief. So, I’m encouraged to see that an NIH-funded team now has preclinical evidence of a promising alternative target for pain-relieving medicines in the brain.2

Rather than activating opioid receptors, the new approach targets receptors for a nerve messenger known as acetylcholine in a portion of the brain involved in pain control. Based on findings from animal models, it appears that treatments targeting acetylcholine could offer pain relief even in people who have reduced responsiveness to opioids. Their findings suggest that the treatment approach has the potential to remain effective in combatting pain long-term and with limited risk for withdrawal symptoms or addiction.

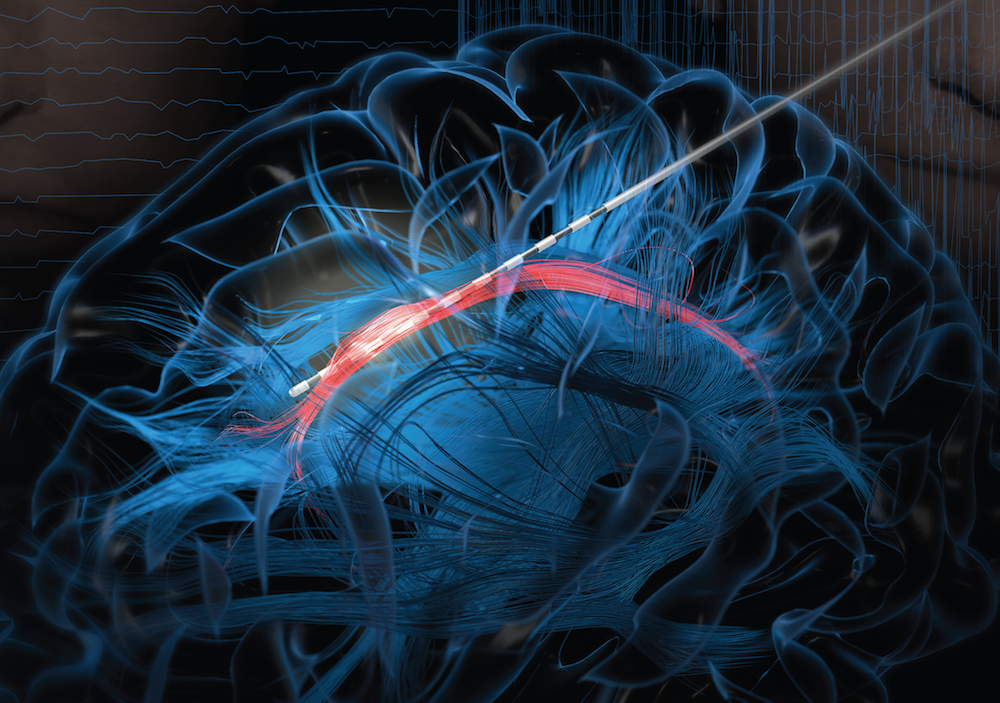

The researchers, led by Daniel McGehee, University of Chicago, focused their attention on non-opioid pathways in the ventrolateral periaqueductal gray (vlPAG), a brain area involved in pain control. They had previously shown that activating acetylcholine receptors, which are part of the vlPAG’s underlying circuitry, could relieve pain.3 However, they found that when the body is experiencing pain, it unexpectedly suppresses acetylcholine rather than releasing more.

To understand how and why this is happening, McGehee and Shivang Sullere, now a postdoctoral fellow at Harvard Medical School, conducted studies in mice to understand how acetylcholine is released under various pain states. They found that mice treated with a drug that stimulates an acetylcholine receptor known as alpha-7 (⍺7) initially led to more activity in the nervous system. But this activity quickly gave way to a prolonged inactive or quiet state that delivered pain relief. Interestingly, this unexpected inhibitory effect lasted for several hours.

Additional studies in mice that had developed a tolerance to opioids showed the same long-lasting pain relief. This encouraging finding was expected since opioids use a pathway separate from acetylcholine. In more good news, the animals didn’t show any signs of dependence or addiction either. For instance, in the absence of pain, they didn’t prefer spending time in environments where they’d receive the ⍺7-targeted drug.

Imaging studies measuring brain activity revealed greater activity in cells expressing ⍺7 with higher levels of pain. When that activity was blocked, pain levels dropped. The finding suggests to the researchers it may be possible to monitor pain levels through brain imaging. It’s also possible the acetylcholine circuitry in the brain may play a role in the process whereby acute or temporary pain becomes chronic.

Finding treatments to modify acetylcholine levels or target acetylcholine receptors may therefore offer a means to treat pain and prevent it from becoming chronic. Encouragingly, drugs acting on these receptors already have been tested for use in people for treating other health conditions. It will now be important to learn whether these existing therapeutics or others like them may act as highly effective, non-addictive painkillers, with important implications for alleviating chronic pain.

References:

[1] NIH HEAL Initiative Research Plan. NIH HEAL Initiative.

[2] Sullere S et al. A cholinergic circuit that relieves pain despite opioid tolerance. Neuron. DOI: 10.1016/j.neuron.2023.08.017 (2023).

[3] Umana IC et al. Nicotinic modulation of descending pain control circuitry. Pain. PMID: 28817416; PMCID: PMC5873975 (2017).

Links:

The Helping to End Addiction Long-term® (HEAL) Initiative (NIH)

Pain (National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke/NIH)

Opioids (National Institute on Drug Abuse/NIH)

Daniel McGehee (University of Chicago, Illinois)

NIH Support: National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, National Institute on Drug Abuse

NIH HEAL Initiative Meets People Where They Are

Posted on by Rebecca Baker, Ph.D., NIH Helping to End Addiction Long-term® (HEAL) Initiative

The opioid crisis continues to devastate communities across America. Dangerous synthetic opioids, like fentanyl, have flooded the illicit drug supply with terrible consequences. Tragically, based on our most-recent data, about 108,000 people in the U.S. die per year from overdoses of opioids or stimulants [1]. Although this complex public health challenge started from our inability to treat pain effectively, chronic pain remains a life-altering problem for 50 million Americans.

To match the size and complexity of the crisis, in 2018 NIH developed the NIH Helping to End Addiction Long-term® (HEAL) Initiative, an aggressive effort involving nearly all of its 27 institutes and centers. Through more than 1,000 research projects, including basic science, clinical testing of new and repurposed drugs, research with communities, and health equity research, HEAL is dedicated to building a new future built on hope.

In this future:

- A predictive tool used during a health visit personalizes treatment for back pain. The tool estimates the probability that a person will benefit from physical therapy, psychotherapy, or surgery.

- Visits to community health clinics and emergency departments serve as routine opportunities to prevent and treat opioid addiction.

- Qualified school staff and pediatricians screen all children for behavioral and other mental health conditions that increase risk for harmful developmental outcomes, including opioid misuse.

- Infants born exposed to opioids during a mother’s pregnancy receive high-quality care—setting them up for a healthy future.

Five years after getting started (and interrupted by a global pandemic), HEAL research is making progress toward achieving this vision. I’ll highlight three ways in which scientific solutions are meeting people where they are today.

A Window of Opportunity for Treatment in the Justice System

Sadly, jails and prisons are “ground zero” for the nation’s opioid crisis. Eighty-five percent of people who are incarcerated have a substance use disorder or a history of substance use. Our vision at HEAL is that every person in jail, prison, or a court-supervised program receives medical care, which includes effective opioid use disorder treatment.

Some research results already are in supporting this approach: A recent HEAL study learned that individuals who had received addiction treatment while in one Massachusetts jail were about 30 percent less likely to be arrested, arraigned, or incarcerated again compared with those incarcerated during the same time period in a neighboring jail that did not offer treatment [2]. Research from the HEAL-supported Justice Community Opioid Innovation Network also is exploring public perceptions about opioid addiction. One such survey showed that most U.S. adults see opioid use disorder as a treatable medical condition rather than as a criminal matter [3]. That’s hopeful news for the future.

A Personalized Treatment Plan for Chronic Back Pain

Half of American adults live with chronic back pain, a major contributor to opioid use. The HEAL-supported Back Pain Consortium (BACPAC) is creating a whole-system model for comprehensive testing of everything that contributes to chronic low back pain, from anxiety to tissue damage. It also includes comprehensive testing of promising pain-management approaches, including psychotherapy, antidepressants, or surgery.

Refining this whole-system model, which is nearing completion, includes finding computer-friendly ways to describe the relationship between the different elements of pain and treatment. That might include developing mathematical equations that describe the physical movements and connections of the vertebrae, discs, and tendons.

Or it might include an artificial intelligence technique called machine learning, in which a computer looks for patterns in existing data, such as electronic health records or medical images. In keeping with HEAL’s all-hands-on-deck approach, BACPAC also conducts clinical trials to test new (or repurposed) treatments and develop new technologies focused on back pain, like a “wearable muscle” to help support the back.

Harnessing Innovation from the Private Sector

The HEAL research portfolio spans basic science to health services research. That allows us to put many shots on goal that will need to be commercialized to help people. Through its research support of small businesses, HEAL funding offers a make-or-break opportunity to advance a great idea to the marketplace, providing a bridge to venture capital or other larger funding sources needed for commercialization.

This bridge also allows HEAL to invest directly in the heart of innovation. Currently, HEAL funds nearly 100 such companies across 20 states. While this is a relatively small portion of all HEAL research, it is science that will make a difference in our communities, and these researchers are passionate about what they do to build a better future.

A couple of current examples of this research passion include: delivery of controlled amounts of non-opioid pain medications after surgery using a naturally absorbable film or a bone glue; immersive virtual reality to help people with opioid use disorder visualize the consequences of certain personal choices; and mobile apps that support recovery, taking medications, or sensing an overdose.

In 2023, HEAL is making headway toward its mission to accelerate development of safe, non-addictive, and effective strategies to prevent and treat pain, opioid misuse, and overdose. We have 314 clinical trials underway and 41 submissions to the Food and Drug Administration to begin clinical testing of investigational new drugs or devices: That number has doubled in the last year. More than 100 projects alone are addressing back pain, and more than 200 projects are studying medications for opioid use disorder.

The nation’s opioid crisis is profoundly difficult and multifaceted—and it won’t be solved with any single approach. Our research is laser-focused on its vision of ending addiction long-term, including improving pain management and expanding access to underused, but highly effective, addiction medications. Every day, we imagine a better future for people with physical and emotional pain and communities that are hurting. Hundreds of researchers and community members across the country are working to achieve a future where people and communities have the tools they need to thrive.

References:

[1] Provisional drug overdose death counts. Ahmad FB, Cisewski JA, Rossen LM, Sutton P. National Center for Health Statistics. 2023.

[2] Recidivism and mortality after in-jail buprenorphine treatment for opioid use disorder. Evans EA, Wilson D, Friedmann PD. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2022 Feb 1;231:109254.

[3] Social stigma toward persons with opioid use disorder: Results from a nationally representative survey of U.S. adults. Taylor BG, Lamuda PA, Flanagan E, Watts E, Pollack H, Schneider J. Subst Use Misuse. 2021;56(12):1752-1764.

Links:

SAMHSA’s National Helpline (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Rockville, MD)

NIH Helping to End Addiction Long-term® (HEAL) Initiative

Video: The NIH HEAL Initiative–HEAL Is Hope

Justice Community Opioid Innovation Network (HEAL)

Back Pain Consortium Research Program (HEAL)

NIH HEAL Initiative 2023 Annual Report (HEAL)

Small Business Programs (HEAL)

Rebecca Baker (HEAL)

Note: Dr. Lawrence Tabak, who performs the duties of the NIH Director, has asked the heads of NIH’s Institutes, Centers, and Offices to contribute occasional guest posts to the blog to highlight some of the interesting science that they support and conduct. This is the 28th in the series of NIH guest posts that will run until a new permanent NIH director is in place.

A Whole Person Approach to Lifting the Burden of Chronic Pain Among Service Members and Veterans

Posted on by Helene M. Langevin, M.D., National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health

Chronic pain and its companion crisis of opioid misuse have taken a terrible toll on Americans. But the impact has been even greater on U.S. service members and veterans, who often deal with the compounded factors of service-related injuries and traumatic stress.

For example, among soldiers in a leading U.S. Army unit, 44 percent had chronic pain and 15 percent used opioids after a combat deployment. That compares to 26 percent and 4 percent, respectively, in the general population [1,2].

This disproportionate burden of chronic pain among veterans [3] and service members led NIH’s National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (NCCIH) to act. We forged a collaboration in 2017 across NIH, U.S. Department of Defense (DOD), and U.S. Department of Veteran’s Affairs (VA) to establish the Pain Management Collaboratory (PMC).

The PMC’s research focusing on the implementation and evaluation of nondrug approaches for the management of pain is urgently needed in the military and across our entire country. Nondrug approaches require a shift in thinking. Rather than focusing solely on blocking pain temporarily using analgesics, nondrug approaches work with the mind and body to promote the resolution of chronic pain and the long-term restoration of health through techniques and practices such as manual therapy, yoga, and mindfulness-based interventions.

Addressing chronic pain in ways that don’t only rely on drugs means addressing underlying issues, such as joints and connective tissue that lack adequate movement or training our brains to “turn down the volume” on pain signals. Using mind and body practices to reduce pain can help promote health in other ways. Possible “fringe benefits” include better sleep, more energy for physical activity, a better mindset for making good nutritional choices, and/or improved mood.

Indeed, there is a growing body of research on the benefits of nondrug approaches to address chronic pain. What is so powerful about PMC is it puts this knowledge to work by embedding research within military health care settings.

The PMC supports a shared resource center and 11 large-scale pragmatic clinical trials. Within this real-world health care setting, the clinical trials have enrolled more than 8,200 participants across 42 veteran and military health systems. These studies offer both strength in numbers and insights into what happens when learnings from controlled clinical trials collide with the realities of health care delivery and the complexities of daily life. [4]

Central to the PMC partnership is whole person health. Too often, we see health through the prism of separate parts—for example, a person’s cardiovascular, digestive, and mental health problems are viewed as co-occurring rather than as interrelated conditions. A whole person framework—a central focus of NCCIH’s current Strategic Plan—brings the parts back together and recognizes that health exists across multiple interconnected body systems and domains: biological, behavioral, social, and environmental.

The VA’s implementation of a whole health model [5] and their unique closed-loop health care system offers an opportunity to deliver care, conduct research, and illustrate what happens when people receive coordinated care that treats the whole person. In fact, VA’s leadership in this area was the impetus for a recent report by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. The report underscored the importance of implementing whole person health care in all settings and for every American.

There are many opportunities ahead for this interagency collaboration. It will help to achieve an important shift, from treating problems one at a time to promoting overall military readiness, resilience, and well-being for U.S. service members and veterans.

Congress appropriated $5 million to NCCIH in fiscal year 2023 to enhance pain research with a special emphasis on military populations. These additional resources will allow NCCIH to support more complex studies in understanding how multiple therapeutic approaches that impact multiple body systems can impact chronic pain.

Meanwhile, programs like the DOD’s Consortium for Health and Military Performance (CHAMP) will continue to translate these lessons learned into accessible pain management information that service members can use in promoting and maintaining their health.

While the PMC’s research program specifically targets the military community, this growing body of knowledge will benefit us all. Understanding how to better manage chronic pain and offering more treatment options for those who want to avoid the risks of opioids will help us all build resilience and restore health of the whole person.

References:

[1] Chronic pain and opioid use in US soldiers after combat deployment. Toblin RL, Quartana PJ, Riviere LA, Walper KC, Hoge CW. JAMA Intern. Med. 2014 Aug;174(8):1400-1401.

[2] Pain and opioids in the military: We must do better. Jonas WB, Schoomaker EB. JAMA Intern. Med. 2014 Aug;174(8):1402-1403

[3] Severe pain in veterans: The effect of age and sex, and comparisons with the general population. Nahin RL. J Pain. 2017 Mar; 18(3):247-254.

[4] Justice and equity in pragmatic clinical trials: Considerations for pain research within integrated health systems. Ali J, Davis AF, Burgess DJ, Rhon DI, Vining R, Young-McCaughan S, Green S, Kerns RD. Learn Health Sys. 2021 Oct 19;6(2): e10291

[5] The APPROACH trial: Assessing pain, patient-reported outcomes, and complementary and integrative health. Zeliadt S, Coggeshall S, Thomas E, Gelman H, Taylor S. Clin. Trials. 2020 Aug;17(4):351-359.

Links:

National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (NIH)

NCCIH Strategic Plan FY 2021-2025: Mapping a Pathway to Research on Whole Person Health (NIH)

Pain Management Collaboratory (Yale University, New Haven, CT)

Whole Health (U.S Department of Veteran’s Affairs, Washington, D.C.)

Consortium for Health and Military Performance (Department of Defense, Bethesda, MD)

Achieving Whole Health: A New Approach for Veterans and the Nation. (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, Washington, D.C.)

Note: Dr. Lawrence Tabak, who performs the duties of the NIH Director, has asked the heads of NIH’s Institutes, Centers, and Offices to contribute occasional guest posts to the blog to highlight some of the interesting science that they support and conduct. This is the 26th in the series of NIH guest posts that will run until a new permanent NIH director is in place.

Tackling Complex Scientific Questions Requires a Team Approach

Posted on by Nora D. Volkow, M.D., National Institute on Drug Abuse

During the COVID-19 pandemic, we have seen unprecedented, rapid scientific collaboration, as experts around the world in discrete, previously disconnected fields, have found ways to collaborate to face a common cause. For example, physicists helped respiratory specialists understand how virus particles could spread in air, leading to improved mitigation strategies. Specialists in cardiovascular science, neuroscience, immunology, and other fields are now working together to understand and address Long COVID. Over the past two years, we have also seen remarkable international sharing of epidemiological data and information on effects of vaccines.

Science is increasingly a team activity, which is true for many fields, not just biomedicine. The professional diversity of research teams reflects the increased complexity of the questions science is called upon to answer. This is especially obvious in the study of the brain, which is the most complex system known to us.

The NIH’s Brain Research Through Advancing Innovative Neurotechnologies® (BRAIN) Initiative, with the goal of vastly enhancing neuroscience through new technologies, includes research teams with neuroscientists, engineers, mathematicians, physicists, data scientists, ethicists, and more. Nearly half (47 percent) of grant awards have multiple principal investigators.

Besides the BRAIN Initiative, other multi-institute NIH research projects are applying team science to complex research questions, such as those related to neurodevelopment, addiction, and pain. The Helping to End Addiction Long-term® Initiative, or NIH HEAL Initiative®, created a team-based research framework to advance promising pain therapeutics quickly to clinical testing.

In the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) study, which is led by NIDA in close partnership with NIH’s National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA), and other NIH institutes, 21 research centers are collecting behavioral, biospecimen, and neuroimaging data from 11,878 children from age 10 through their teens. Teams led by experts in adolescent psychiatry, developmental psychology, and pediatrics interview participants and their families. These experts then gather a battery of health metrics from psychological, cognitive, sociocultural, and physical assessments, including collection and analysis of various kinds of biospecimens (blood, saliva). Further, experts in biophysics gather information on the structure and function of participants’ brains every two years.

A similar study of young children in the first decade of life beginning with the prenatal period, the HEALthy Brain and Child Development (HBCD) study, supported by HEAL, NIDA, and several other NIH institutes and centers, is now underway at 25 research sites across the country. A range of scientific specialists, similar to that in the ABCD study, is involved in this effort. In this case, they are aided by experts in obstetric care and in infant neuroimaging.

For both of these studies, teams of data scientists validate and curate all the information generated and make it available to researchers across the world. This makes it possible to investigate complex questions such as human neurodevelopmental diversity and the effects of genes and social experiences and their relation to mental health. More than half of the publications using ABCD data have been authored by non-ABCD investigators taking advantage of the open-access format.

Yet, institutions that conduct and fund science—including NIH—have been slow to support and reward collaboration. Because authorship and funding are so important in tenure and promotion decisions at universities, for example, an individual’s contribution to larger, multi-investigator projects on which they may not be the grantee or lead author on a study publication may carry less weight.

For this reason, early-career scientists may be particularly reluctant to collaborate on team projects. Among the recommendations of a 2015 National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM) report, Enhancing the Effectiveness of Team Science, was that universities and other institutions should find effective ways to give credit for team-based work to assist promotion and tenure committees.

The strongest teams will be diverse in other respects, not just scientific expertise. Besides more actively fostering productive collaborations across disciplines, NIH is making a more concerted effort to promote racial equity and inclusivity in our research workforce, both through the NIH UNITE Initiative and through Institute-specific initiatives like NIDA’s Racial Equity Initiative.

To promote diversity, inclusivity, and accessibility in research, the BRAIN Initiative recently added a requirement in most of its funding opportunity announcements (FOAs) that has applicants include a Plan for Enhancing Diverse Perspectives (PEDP) in the proposed research. The PEDPs are evaluated and scored during the peer review as part of the holistic considerations used to inform funding decisions. These long-overdue measures will not only ensure that NIH-funded science is more diverse, but they are also important steps toward studying and addressing social determinants of health and the health disparities that exist for so many conditions.

Increasingly, scientific discovery is as much about exploring new connections between different kinds of researchers as it is about finding new relationships among different kinds of scientific databases. The challenges before us are great—ending the COVID pandemic, finding a solution to the addiction and overdose crisis, and so many others—and increased collaboration between scientists will give us the greatest chance to successfully overcome these challenges.

Links:

Nora Volkow’s Blog (National Institute on Drug Abuse/NIH)

Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development Study

Brain Research Through Advancing Innovative Neurotechnologies® (BRAIN) Initiative (NIH)

Racial Equity Initiative (NIDA)

Note: Acting NIH Director Lawrence Tabak has asked the heads of NIH’s Institutes and Centers (ICs) to contribute occasional guest posts to the blog to highlight some of the interesting science that they support and conduct. This is the 13th in the series of NIH IC guest posts that will run until a new permanent NIH director is in place.

Research to Address the Real-Life Challenges of Opioid Crisis

Posted on by Lawrence Tabak, D.D.S., Ph.D.

While great progress has been made in controlling the COVID-19 pandemic, America’s opioid crisis continues to evolve in unexpected ways. The opioid crisis, which worsened during the pandemic and now involves the scourge of fentanyl, claims more than 70,000 lives each year in the United States [1]. But throughout the pandemic, NIH has continued its research efforts to help people with a substance use disorder find the help that they so need. These efforts include helping to find relief for the millions of Americans who live with severe and chronic pain.

Recently, I traveled to Atlanta for the Rx and Illicit Drug Summit 2022. While there, I moderated an evening fireside chat with two of NIH’s leaders in combating the opioid crisis: Nora Volkow, director of the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA); and Rebecca Baker, director of Helping to End Addiction Long-term® (HEAL) initiative. What follows is an edited, condensed transcript of our conversation.

Tabak: Let’s start with Nora. When did the opioid crisis begin, and how has it changed over the years

Volkow: It started just before the year 2000 with the over-prescription of opioid medications. People were becoming addicted to them, many from diverted product. By 2010, CDC developed guidelines that decreased the over-prescription. But then, we saw a surge in heroin use. That turned the opioid crisis into two problems: prescription opioids and heroin.

In 2016, we encountered the worst scourge yet. It is fentanyl, an opioid that’s 50 times more potent than heroin. Fentanyl is easily manufactured, and it’s easier than other opioids to hide and transport across the border. That makes this drug very profitable.

What we have seen during the pandemic is the expansion of fentanyl use in the United States. Initially, fentanyl made its way to the Northeast; now it’s everywhere. Initially, it was used to contaminate heroin; now it’s used to contaminate cocaine, methamphetamine, and, most recently, illicit prescription drugs, such as benzodiazepines and stimulants. With fentanyl contaminating all these drugs, we’re also seeing a steep rise in mortality from cocaine and methamphetamine use in African Americans, American Indians, and Alaska natives.

Tabak: What about teens? A recent study in the journal JAMA reported for the first time in a decade that overdose deaths among U.S. teens rose dramatically in 2020 and kept rising through 2021 [2]. Is fentanyl behind this alarming increase?

Volkow: Yes, and it has us very concerned. The increase also surprised us. Over the past decade, we have seen a consistent decrease in adolescent drug use. In fact, there are some drugs that have the lowest usage rates that we’ve ever recorded. To observe this more than doubling of overdose deaths from fentanyl before the COVID pandemic was a major surprise.

Adolescents don’t typically use heroin, nor do they seek out fentanyl. Our fear is adolescents are misusing illicit prescriptions contaminated with fentanyl. Because an estimated 30-40 percent of those tainted pills contain levels of fentanyl that can kill you, it becomes a game of Russian roulette. This dangerous game is being played by adolescents who may just be experimenting with illicit pills.

Tabak: For people with substance use disorders, there are new ways to get help. In fact, one of the very few positive outcomes of the pandemic is the emergence of telehealth. If we can learn to navigate the various regulatory issues, do you see a place for telehealth going forward?

Volkow: When you have a crisis like this one, there’s a real need to accelerate interventions and innovation like telehealth. It certainly existed before the pandemic, and we knew that telehealth was beneficial for the treatment of substance use disorders. But it was very difficult to get reimbursement, making access extremely limited.

When COVID overwhelmed emergency departments, people with substance use disorders could no longer get help there. Other interventions were needed, and telehealth helped fill the void. It also had the advantage of reaching rural populations in states such as Kentucky, West Virginia, Ohio, where easy access to treatment or unique interventions can be challenging. In many prisons and jails, administrators worried about bringing web-based technologies into their facilities. So, in partnership with the Justice Department, we have created networks that now will enable the entry of telehealth into jails and prisons.

Tabak: Rebecca, it’s been four years since the HEAL initiative was announced at this very summit in 2018. How is the initiative addressing this ever-evolving crisis?

Baker: We’ve launched over 600 research projects across the country at institutions, hospitals, and research centers in a broad range of scientific areas. We’re working to come up with new treatment options for pain and addiction. There’s exciting research underway to address the craving and sleep disruption caused by opioid withdrawal. This research has led to over 20 investigational new drug applications to the FDA. Some are for repurposed drugs, compounds that have already been shown to be safe and effective for treating other health conditions that may also have value for treating addiction. Some are completely novel. We have also initiated the first testing of an opioid vaccine, for oxycodone, to prevent relapse and overdose in high-risk individuals.

Tabak: What about clinical research?

Baker: We’re testing multiple different treatments for both pain and addiction. Not everyone with pain is the same, and not every treatment is going to work the same for everyone. We’re conducting clinical trials in real-world settings to find out what works best for patients. We’re also working to implement lifesaving, evidence-based interventions into places where people seek help, including faith, community, and criminal justice settings.

Tabak: The pandemic highlighted inequities in our health-care system. These inequities afflict individuals and populations who are struggling with addiction and overdose. Nora, what needs to be done to address the social determinants of racial disparities?

Volkow: This is an extraordinarily important question. As you noted, certain racial and ethnic groups had disproportionately higher mortality rates from COVID. We have seen the same with overdose deaths. For example, we know that the most important intervention for preventing overdoses is to initiate medications such as methadone, buprenorphine or vivitrol. But Black Americans are initiated on these medications at least five years later than white Americans. Similarly, Black Americans also are less likely to receive the overdose-reversal medication naloxone.

That’s not right. We must ask what are the core causes of limited access to high-quality health care? Low income is a major contributing factor. Helping people get an education is one of the most important factors to address it. Another factor is distrust of the medical system. When racial and ethnic discrimination is compounded by discrimination because a person has a substance use disorder, you can see why it becomes very difficult for some to seek help. As a society, we certainly need to address racial discrimination. But we also need to address discrimination against substance use disorders in people of all races who are vulnerable.

Baker: Our research is tackling these barriers head on with a direct focus on stigma. As Nora alluded to, oftentimes providers may not offer lifesaving medication to some patients, and we’ve developed and are testing research training to help providers recognize and address their own biases and behaviors in caring for different populations.

We have supported research on the drivers of equity. A big part of this is engaging with people with lived experience and making sure that the interventions being designed are feasible in the real world. Not everyone has access to health insurance, transportation, childcare—the support that they may need to sustain treatment and recovery. In short, our research is seeking ways to enhance linkage to treatment.

Nora mentioned the importance of telehealth in improving equity. That’s another research focus, as well as developing tailored, culturally appropriate interventions for addressing pain and addiction. When you have this trust issue, you can’t always go in with a prescription or a recommendation from a physician. So in American and Alaskan native communities, we’re integrating evidence-based prevention approaches with traditional practices like wellness gatherings, cooking together, use of sage and spirituality, along with community support, and seeing if that encourages and increases the uptake of these prevention approaches in communities that need it so much.

Tabak: The most heartbreaking impact of the opioid crisis has been the infants born dependent on opioids. Rebecca, what’s being done to help the very youngest victims of the opioid crisis born with neonatal opioid withdrawal syndrome, or NOWS?

Baker: Thanks for asking about the infants. Babies with NOWS undergo withdrawal at birth and cry inconsolably, often with extreme stomach upset and sometimes even with seizures. Our research found that hospitals across the country vary greatly in how they treat these babies. Our program, ACT NOW, or Advancing Clinical Trials in Neonatal Opioid Withdrawal, aims to provide concrete guidance for nurses in the NICU treating these infants. One of the studies that we call Eat, Sleep, Console focuses on the abilities of the baby. Our researchers are testing if the ability to eat, sleep, or be consoled increases bonding with the mother and if it reduces time in the hospital, as well as other long-term health outcomes.

In addition to that NOWS program, we’ve also launched the HEALthy Brain and Child Development Study, or HBCD, that seeks to understand the long-term consequences of opioid exposure together with all the other environmental and other factors the baby experiences as they grow up. The hope is that together these studies will inform future prevention and treatment efforts for both mental health and also substance use and addiction.

Tabak: As the surge in heroin use and appearance of fentanyl has taught us, the opioid crisis has ever-changing dynamics. It tells us that we need better prevention strategies. Rebecca, could you share what HEAL is doing about prevention?

Baker: Prevention has always been a core component of the HEAL Initiative in a number of ways. The first is by preventing unnecessary opioid exposures through enhanced and evidence-based pain management. HEAL is supporting research on new small molecules, new devices, new biologic therapeutics that could treat pain and distinct pain conditions without opioids. And we’re also researching and providing guidance for clinicians on strategies for managing pain without medication, including acupuncture and physical therapy. They can often be just as effective and more sustainable.

HEAL is also working to address risky opioid use outside of pain management, especially in high-risk groups. That includes teens and young adults who may be experimenting, people lacking stable housing, patients who are on high-dose opioids for pain management, or they maybe have gone off high-dose opioids but still have them in their possession.

Finally, to prevent overdose we have to give naloxone to the people who need it. The HEALing Communities Study has taken some really innovative approaches to providing naloxone in libraries, on the beach, and places where overdoses are actually happening, not just in medical settings. And I think that will be, in our fight against the overdose crisis, a key tool.

Volkow: Larry, I’d like to add a few words on prevention. There are evidence-based interventions that have been shown to be quite effective for preventing substance use among teenagers and young adults. And yet, they are not implemented. We have evidence-based interventions that work for prevention. We have evidence-based interventions that work for treatment. But we don’t provide the resources for their implementation, nor do we train the personnel that can carry it over.

Science can give us tools, but if we do not partner at the next level for their implementation, those tools do not have the impact they should have. That’s why I always bring up the importance of policy in the implementation phase.

Tabak: Rebecca, the opioid crisis got started with a lack of good options for treating pain. Could you share with us how HEAL’s research efforts are addressing the needs of millions of Americans who experience both chronic pain and opioid use disorder?

Baker: It’s so important to remember people with pain. We can’t let our efforts to combat the opioid crisis make us lose sight of the needs of the millions of Americans with pain. One hundred million Americans experience pain; half of them have severe pain, daily pain, and 20 million have such severe pain that they can’t do things that are important to them in their life, family, job, other activities that bring their life meaning.

HEAL recognizes that these individuals need better options. New non-addictive pain treatments. But as you say, there is a special need for people with a substance use disorder who also have pain. They desperately need new and better options. And so we recently, through the HEAL Initiative, launched a new trials network that couples medication-based treatment for opioid use disorders, so that’s methadone or buprenorphine, with new pain-management strategies such as psychotherapy or yoga in the opioid use disorder treatment setting so that you’re not sending them around to lots of different places. And our hope is that this integrated approach will address some of the fragmented healthcare challenges that often results in poor care for these patients.

My last point would be that some patients need opioids to function. We can’t forget as we make sure that we are limiting risky opioid use that we don’t take away necessary opioids for these patients, and so our future research will incorporate ways of making sure that they receive needed treatment while also preventing them from the risks of opioid use disorder.

Tabak: Rebecca, let me ask you one more question. What do you want the folks here to remember about HEAL?

Baker: HEAL stands for Helping to End Addiction Long-term, and nobody knows more than the people in this room how challenging and important that really is. We’ve heard a little bit about the great promise of our research and some of the advances that are coming through our research pipeline, new treatments, new guidance for clinicians and caregivers. I want everyone to know that we want to work with you. By working together, I’m confident that we will tailor these new advances to meet the individual needs of the patients and populations that we serve.

Tabak: Nora, what would you like to add?

Volkow: This afternoon, I met with two parents who told me the story of how they lost their daughter to an overdose. They showed me pictures of this fantastic girl, along with her drawings. Whenever we think about overdose deaths in America, the sheer number—75,000—can make us indifferent. But when you can focus on one person and feel the love surrounding that life, you remember the value of this work.

Like in COVID, substance use disorders are a painful problem that we’re all experiencing in some way. They may have upset our lives. But they may have brought us together and, in many instances, brought out the best that humans can do. The best, to me, is caring for one another and taking the responsibility of helping those that are most vulnerable. I believe that science has a purpose. And here we have a purpose: to use science to bring solutions that can prevent and treat those suffering from substance use disorders.

Tabak: Thanks to both of you for this enlightening conversation.

References:

[1] Drug overdose deaths, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, February 22, 2022.

[2] Trends in drug overdose deaths among US adolescents, January 2010 to June 2021. Friedman J. et al. JAMA. 2022 Apr 12;327(14):1398-1400.

Links:

Video: Evening Plenary with NIH’s Lawrence Tabak, Nora Volkow, and Rebecca Baker (Rx and Illicit Drug Summit 2022)

SAMHSA’s National Helpline (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Rockville, MD)

Opioids (National Institute on Drug Abuse/NIH)

Fentanyl (NIDA)

Helping to End Addiction Long-term®(HEAL) Initiative (NIH)

Rebecca Baker (HEAL/NIH)

Nora Volkow (NIDA)

NIH’s Nobel Winners Demonstrate Value of Basic Research

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Last week was a big one for both NIH and me. Not only did I announce my plans to step down as NIH Director by year’s end to return to my lab full-time, I was reminded by the announcement of the 2021 Nobel Prizes of what an honor it is to be affiliated an institution with such a strong, sustained commitment to supporting basic science.

This year, NIH’s Nobel excitement started in the early morning hours of October 4, when two NIH-supported neuroscientists in California received word from Sweden that they had won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine. One “wake up” call went to David Julius, University of California, San Francisco (UCSF), who was recognized for his groundbreaking discovery of the first protein receptor that controls thermosensation, the body’s perception of temperature. The other went to his long-time collaborator, Ardem Patapoutian, Scripps Research Institute, La Jolla, CA, for his seminal work that identified the first protein receptor that controls our sense of touch.

But the good news didn’t stop there. On October 6, the 2021 Nobel Prize in Chemistry was awarded to NIH-funded chemist David W.C. MacMillan of Princeton University, N.J., who shared the honor with Benjamin List of Germany’s Max Planck Institute. (List also received NIH support early in his career.)

The two researchers were recognized for developing an ingenious tool that enables the cost-efficient construction of “greener” molecules with broad applications across science and industry—including for drug design and development.

Then, to turn this into a true 2021 Nobel Prize “hat trick” for NIH, we learned on October 12 that two of this year’s three Nobel winners in Economic Sciences had been funded by NIH. David Card, an NIH-supported researcher at University of California, Berkley, was recognized “for his empirical contributions to labor economics.” He shared the 2021 prize with NIH grantee Joshua Angrist of Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, and his colleague Guido Imbens of Stanford University, Palo Alto, CA, “for their methodological contributions to the analysis of causal relationships.” What a year!

The achievements of these and NIH’s 163 past Nobel Prize winners stand as a testament to the importance of our agency’s long and robust history of investing in basic biomedical research. In this area of research, scientists ask fundamental questions about how life works. The answers they uncover help us to understand the principles, mechanisms, and processes that underlie living organisms, including the human body in sickness and health.

What’s more, each advance builds upon past discoveries, often in unexpected ways and sometimes taking years or even decades before they can be translated into practical results. Recent examples of life-saving breakthroughs that have been built upon years of fundamental biomedical research include the mRNA vaccines for COVID-19 and the immunotherapy approaches now helping people with many types of cancer.

Take the case of the latest Nobels. Fundamental questions about how the human body responds to medicinal plants were the initial inspiration behind the work of UCSF’s Julius. He’d noticed that studies from Hungary found that a natural chemical in chili peppers, called capsaicin, activated a subgroup of neurons to create the painful, burning sensation that most of us have encountered from having a bit too much hot sauce. But what wasn’t known was the molecular mechanism by which capsaicin triggered that sensation.

In 1997, having settled on the best experimental approach to study this question, Julius and colleagues screened millions of DNA fragments corresponding to genes expressed in the sensory neurons that were known to interact with capsaicin. In a matter of weeks, they had pinpointed the gene encoding the protein receptor through which capsaicin interacts with those neurons [1]. Julius and team then determined in follow-up studies that the receptor, later named TRPV1, also acts as a thermal sensor on certain neurons in the peripheral nervous system. When capsaicin raises the temperature to a painful range, the receptor opens a pore-like ion channel in the neuron that then transmit a signal for the unpleasant sensation on to the brain.

In collaboration with Patapoutian, Julius then turned his attention from hot to cold. The two used the chilling sensation of the active chemical in mint, menthol, to identify a protein called TRPM8, the first receptor that senses cold [2, 3]. Additional pore-like channels related to TRPV1 and TRPM8 were identified and found to be activated by a range of different temperatures.

Taken together, these breakthrough discoveries have opened the door for researchers around the world to study in greater detail how our nervous system detects the often-painful stimuli of hot and cold. Such information may well prove valuable in the ongoing quest to develop new, non-addictive treatments for pain. The NIH is actively pursuing some of those avenues through its Helping to End Addiction Long-termSM (HEAL) Initiative.

Meanwhile, Patapoutian was busy cracking the molecular basis of another basic sense: touch. First, Patapoutian and his collaborators identified a mouse cell line that produced a measurable electric signal when individual cells were poked. They had a hunch that the electrical signal was generated by a protein receptor that was activated by physical pressure, but they still had to identify the receptor and the gene that coded for it. The team screened 71 candidate genes with no luck. Then, on their 72nd try, they identified a touch receptor-coding gene, which they named Piezo1, after the Greek word for pressure [4].

Patapoutian’s group has since found other Piezo receptors. As often happens in basic research, their findings have taken them in directions they never imagined. For example, they have discovered that Piezo receptors are involved in controlling blood pressure and sensing whether the bladder is full. Fascinatingly, these receptors also seem to play a role in controlling iron levels in red blood cells, as well as controlling the actions of certain white blood cells, called macrophages.

Turning now to the 2021 Nobel in Chemistry, the basic research of MacMillan and List has paved the way for addressing a major unmet need in science and industry: the need for less expensive and more environmentally friendly catalysts. And just what is a catalyst? To build the synthetic molecules used in drugs and a wide range of other materials, chemists rely on catalysts, which are substances that control and accelerate chemical reactions without becoming part of the final product.

It was long thought there were only two major categories of catalysts for organic synthesis: metals and enzymes. But enzymes are large, complex proteins that are hard to scale to industrial processes. And metal catalysts have the potential to be toxic to workers, as well as harmful to the environment. Then, about 20 years ago, List and MacMillan, working independently from each other, created a third type of catalyst. This approach, known as asymmetric organocatalysis [5, 6], builds upon small organic molecule catalysts that have a stable framework of carbon atoms, to which more active chemical groups can attach, often including oxygen, nitrogen, sulfur, or phosphorus.

Organocatalysts have gone on to be applied in ways that have proven to be more cost effective and environmentally friendly than using traditional metal or enzyme catalysts. In fact, this precise new tool for molecular construction is now being used to build everything from new pharmaceuticals to light-absorbing molecules used in solar cells.

That brings us to the Nobel Prize in the Economic Sciences. This year’s laureates showed that it’s possible to reach cause-and-effect answers to questions in the social sciences. The key is to evaluate situations in groups of people being treated differently, much like the design of clinical trials in medicine. Using this “natural experiment” approach in the early 1990s, David Card produced novel economic analyses, showing an increase in the minimum wage does not necessarily lead to fewer jobs. In the mid-1990s, Angrist and Imbens then refined the methodology of this approach, showing that precise conclusions can be drawn from natural experiments that establish cause and effect.

Last year, NIH added the names of three scientists to its illustrious roster of Nobel laureates. This year, five more names have been added. Many more will undoubtedly be added in the years and decades ahead. As I’ve said many times over the past 12 years, it’s an extraordinary time to be a biomedical researcher. As I prepare to step down as the Director of this amazing institution, I can assure you that NIH’s future has never been brighter.

References:

[1] The capsaicin receptor: a heat-activated ion channel in the pain pathway. Caterina MJ, Schumacher MA, Tominaga M, Rosen TA, Levine JD, Julius D. Nature 1997:389:816-824.

[2] Identification of a cold receptor reveals a general role for TRP channels in thermosensation. McKemy DD, Neuhausser WM, Julius D. Nature 2002:416:52-58.

[3] A TRP channel that senses cold stimuli and menthol. Peier AM, Moqrich A, Hergarden AC, Reeve AJ, Andersson DA, Story GM, Earley TJ, Dragoni I, McIntyre P, Bevan S, Patapoutian A. Cell 2002:108:705-715.

[4] Piezo1 and Piezo2 are essential components of distinct mechanically activated cation channels. Coste B, Mathur J, Schmidt M, Earley TJ, Ranade S, Petrus MJ, Dubin AE, Patapoutian A. Science 2010:330: 55-60.

[5] Proline-catalyzed direct asymmetric aldol reactions. List B, Lerner RA, Barbas CF. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 122, 2395–2396 (2000).

[6] New strategies for organic catalysis: the first highly enantioselective organocatalytic Diels-AlderReaction. Ahrendt KA, Borths JC, MacMillan DW. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000, 122, 4243-4244.

Links:

Basic Research – Digital Media Kit (NIH)

Curiosity Creates Cures: The Value and Impact of Basic Research (National Institute of General Medical Sciences/NIH)

Explaining How Research Works (NIH)

NIH Basics, Collins FS, Science, 3 Aug 2012. 337; 6094: 503.

NIH’s Commitment to Basic Science, Mike Lauer, Open Mike Blog, March 25, 2016

Nobel Laureates (NIH)

The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 2021 (The Nobel Assembly at the Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden)

Video: Announcement of the 2021 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine (YouTube)

The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 2021 (The Nobel Assembly at the Karolinska Institutet)

Video: Announcement of the 2021 Nobel Prize in Chemistry (YouTube)

The Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences (The Nobel Assembly at the Karolinska Institutet)

Video: Announcement of the 2021 Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences (YouTube)

Julius Lab (University of California San Francisco)

The Patapoutian Lab (Scripps Research, La Jolla, CA)

Benjamin List (Max-Planck-Institut für Kohlenforschung, Mülheim an der Ruhr, Germany)

The MacMillan Group (Princeton University, NJ)

David Card (University of California, Berkeley)

Joshua Angrist (Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge)

NIH Support:

David Julius: National Institute of Neurological Diseases and Stroke; National Institute of General Medical Sciences; National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research

Ardem Patapoutian: National Institute of Neurological Diseases and Stroke; National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute

David W.C. MacMillan: National Institute of General Medical Sciences

David Card: National Institute on Aging; Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development

Joshua Angrist: Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development

Could CRISPR Gene-Editing Technology Be an Answer to Chronic Pain?

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Gene editing has shown great promise as a non-heritable way to treat a wide range of conditions, including many genetic diseases and more recently, even COVID-19. But could a version of the CRISPR gene-editing tool also help deliver long-lasting pain relief without the risk of addiction associated with prescription opioid drugs?

In work recently published in the journal Science Translational Medicine, researchers demonstrated in mice that a modified version of the CRISPR system can be used to “turn off” a gene in critical neurons to block the transmission of pain signals [1]. While much more study is needed and the approach is still far from being tested in people, the findings suggest that this new CRISPR-based strategy could form the basis for a whole new way to manage chronic pain.

This novel approach to treating chronic pain occurred to Ana Moreno, the study’s first author, when she was a Ph.D. student in the NIH-supported lab of Prashant Mali, University of California, San Diego. Mali had been studying a wide range of novel gene- and cell-based therapeutics. While reading up on both, Moreno landed on a paper about a mutation in a gene that encodes a pain-enhancing protein in spinal neurons called NaV1.7.

Moreno read that kids born with a loss-of-function mutation in this gene have a rare condition known as congenital insensitivity to pain (CIP). They literally don’t sense and respond to pain. Although these children often fail to recognize serious injuries because of the absence of pain to alert them, they have no other noticeable physical effects of the condition.

For Moreno, something clicked. What if it were possible to engineer a new kind of treatment—one designed to turn this gene down or fully off and stop people from feeling chronic pain?

Moreno also had an idea about how to do it. She’d been working on repressing or “turning off” genes using a version of CRISPR known as “dead” Cas9 [2]. In CRISPR systems designed to edit DNA, the Cas9 enzyme is often likened to a pair of scissors. Its job is to cut DNA in just the right spot with the help of an RNA guide. However, CRISPR-dead Cas9 no longer has any ability to cut DNA. It simply sticks to its gene target and blocks its expression. Another advantage is that the system won’t lead to any permanent DNA changes, since any treatment based on CRISPR-dead Cas9 might be safely reversed.

After establishing that the technique worked in cells, Moreno and colleagues moved to studies of laboratory mice. They injected viral vectors carrying the CRISPR treatment into mice with different types of chronic pain, including inflammatory and chemotherapy-induced pain.

Moreno and colleagues determined that all the mice showed evidence of durable pain relief. Remarkably, the treatment also lasted for three months or more and, importantly, without any signs of side effects. The researchers are also exploring another approach to do the same thing using a different set of editing tools called zinc finger nucleases (ZFNs).

The researchers say that one of these approaches might one day work for people with a large number of chronic pain conditions that involve transmission of the pain signal through NaV1.7. That includes diabetic polyneuropathy, sciatica, and osteoarthritis. It also could provide relief for patients undergoing chemotherapy, along with those suffering from many other conditions. Moreno and Mali have co-founded the spinoff company Navega Therapeutics, San Diego, CA, to work on the preclinical steps necessary to help move their approach closer to the clinic.

Chronic pain is a devastating public health problem. While opioids are effective for acute pain, they can do more harm than good for many chronic pain conditions, and they are responsible for a nationwide crisis of addiction and drug overdose deaths [3]. We cannot solve any of these problems without finding new ways to treat chronic pain. As we look to the future, it’s hopeful that innovative new therapeutics such as this gene-editing system could one day help to bring much needed relief.

References:

[1] Long-lasting analgesia via targeted in situ repression of NaV1.7 in mice. Moreno AM, Alemán F, Catroli GF, Hunt M, Hu M, Dailamy A, Pla A, Woller SA, Palmer N, Parekh U, McDonald D, Roberts AJ, Goodwill V, Dryden I, Hevner RF, Delay L, Gonçalves Dos Santos G, Yaksh TL, Mali P. Sci Transl Med. 2021 Mar 10;13(584):eaay9056.

[2] Nuclease dead Cas9 is a programmable roadblock for DNA replication. Whinn KS, Kaur G, Lewis JS, Schauer GD, Mueller SH, Jergic S, Maynard H, Gan ZY, Naganbabu M, Bruchez MP, O’Donnell ME, Dixon NE, van Oijen AM, Ghodke H. Sci Rep. 2019 Sep 16;9(1):13292.

[3] Drug Overdose Deaths. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Links:

Congenital insensitivity to pain (National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences/NIH)

Opioids (National Institute on Drug Abuse/NIH)

Mali Lab (University of California, San Diego)

Navega Therapeutics (San Diego, CA)

NIH Support: National Human Genome Research Institute; National Cancer Institute; National Institute of General Medical Sciences; National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke

Discovering a Source of Laughter in the Brain

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

If laughter really is the best medicine, wouldn’t it be great if we could learn more about what goes on in the brain when we laugh? Neuroscientists recently made some major progress on this front by pinpointing a part of the brain that, when stimulated, never fails to induce smiles and laughter.

In their study conducted in three patients undergoing electrical stimulation brain mapping as part of epilepsy treatment, the NIH-funded team found that stimulation of a specific tract of neural fibers, called the cingulum bundle, triggered laughter, smiles, and a sense of calm. Not only do the findings shed new light on the biology of laughter, researchers hope they may also lead to new strategies for treating a range of conditions, including anxiety, depression, and chronic pain.

In people with epilepsy whose seizures are poorly controlled with medication, surgery to remove seizure-inducing brain tissue sometimes helps. People awaiting such surgeries must first undergo a procedure known as intracranial electroencephalography (iEEG). This involves temporarily placing 10 to 20 arrays of tiny electrodes in the brain for up to several weeks, in order to pinpoint the source of a patient’s seizures in the brain. With the patient’s permission, those electrodes can also enable physician-researchers to stimulate various regions of the patient’s brain to map their functions and make potentially new and unexpected discoveries.

In the new study, published in The Journal of Clinical Investigation, Jon T. Willie, Kelly Bijanki, and their colleagues at Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, looked at a 23-year-old undergoing iEEG for 8 weeks in preparation for surgery to treat her uncontrolled epilepsy [1]. One of the electrodes implanted in her brain was located within the cingulum bundle and, when that area was stimulated for research purposes, the woman experienced an uncontrollable urge to laugh. Not only was the woman given to smiles and giggles, she also reported feeling relaxed and calm.

As a further and more objective test of her mood, the researchers asked the woman to interpret the expression of faces on a computer screen as happy, sad, or neutral. Electrical stimulation to the cingulum bundle led her to see those faces as happier, a sign of a generally more positive mood. A full evaluation of her mental state also showed she was fully aware and alert.

To confirm the findings, the researchers looked to two other patients, a 40-year-old man and a 28-year-old woman, both undergoing iEEG in the course of epilepsy treatment. In those two volunteers, stimulation of the cingulum bundle also triggered laughter and reduced anxiety with otherwise normal cognition.

Willie notes that the cingulum bundle links many brain areas together. He likens it to a super highway with lots of on and off ramps. He suspects the spot they’ve uncovered lies at a key intersection, providing access to various brain networks regulating mood, emotion, and social interaction.

Previous research has shown that stimulation of other parts of the brain can also prompt patients to laugh. However, what makes stimulation of the cingulum bundle a particularly promising approach is that it not only triggers laughter, but also reduces anxiety.

The new findings suggest that stimulation of the cingulum bundle may be useful for calming patients’ anxieties during neurosurgeries in which they must remain awake. In fact, Willie’s team did so during their 23-year-old woman’s subsequent epilepsy surgery. Each time she became distressed, the stimulation provided immediate relief. Also, if traditional deep brain stimulation or less invasive means of brain stimulation can be developed and found to be safe for long-term use, they may offer new ways to treat depression, anxiety disorders, and/or chronic pain.

Meanwhile, Willie’s team is hard at work using similar approaches to map brain areas involved in other aspects of mood, including fear, sadness, and anxiety. Together with the multidisciplinary work being mounted by the NIH-led BRAIN Initiative, these kinds of studies promise to reveal functionalities of the human brain that have previously been out of reach, with profound consequences for neuroscience and human medicine.

Reference:

[1] Cingulum stimulation enhances positive affect and anxiolysis to facilitate awake craniotomy. Bijanki KR, Manns JR, Inman CS, Choi KS, Harati S, Pedersen NP, Drane DL, Waters AC, Fasano RE, Mayberg HS, Willie JT. J Clin Invest. 2018 Dec 27.

Links:

Video: Patient’s Response (Bijanki et al. The Journal of Clinical Investigation)

Epilepsy Information Page (National Institute of Neurological Disease and Stroke/NIH)

Jon T. Willie (Emory University, Atlanta, GA)

NIH Support: National Institute of Neurological Disease and Stroke; National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences

Next Page