brain surgery

Discovering a Source of Laughter in the Brain

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

If laughter really is the best medicine, wouldn’t it be great if we could learn more about what goes on in the brain when we laugh? Neuroscientists recently made some major progress on this front by pinpointing a part of the brain that, when stimulated, never fails to induce smiles and laughter.

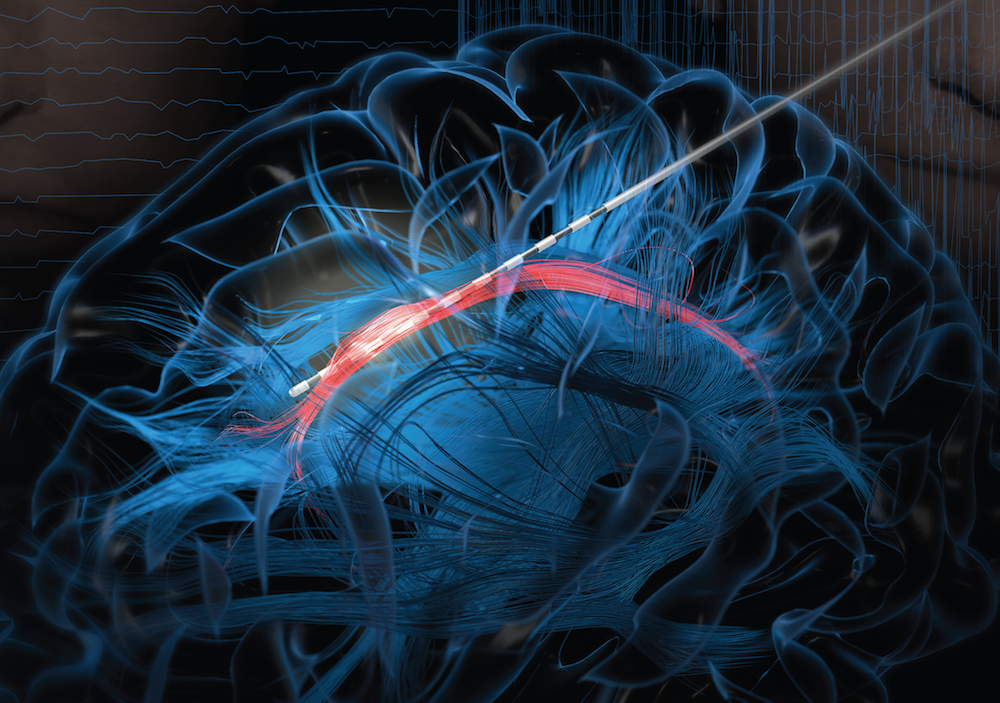

In their study conducted in three patients undergoing electrical stimulation brain mapping as part of epilepsy treatment, the NIH-funded team found that stimulation of a specific tract of neural fibers, called the cingulum bundle, triggered laughter, smiles, and a sense of calm. Not only do the findings shed new light on the biology of laughter, researchers hope they may also lead to new strategies for treating a range of conditions, including anxiety, depression, and chronic pain.

In people with epilepsy whose seizures are poorly controlled with medication, surgery to remove seizure-inducing brain tissue sometimes helps. People awaiting such surgeries must first undergo a procedure known as intracranial electroencephalography (iEEG). This involves temporarily placing 10 to 20 arrays of tiny electrodes in the brain for up to several weeks, in order to pinpoint the source of a patient’s seizures in the brain. With the patient’s permission, those electrodes can also enable physician-researchers to stimulate various regions of the patient’s brain to map their functions and make potentially new and unexpected discoveries.

In the new study, published in The Journal of Clinical Investigation, Jon T. Willie, Kelly Bijanki, and their colleagues at Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, looked at a 23-year-old undergoing iEEG for 8 weeks in preparation for surgery to treat her uncontrolled epilepsy [1]. One of the electrodes implanted in her brain was located within the cingulum bundle and, when that area was stimulated for research purposes, the woman experienced an uncontrollable urge to laugh. Not only was the woman given to smiles and giggles, she also reported feeling relaxed and calm.

As a further and more objective test of her mood, the researchers asked the woman to interpret the expression of faces on a computer screen as happy, sad, or neutral. Electrical stimulation to the cingulum bundle led her to see those faces as happier, a sign of a generally more positive mood. A full evaluation of her mental state also showed she was fully aware and alert.

To confirm the findings, the researchers looked to two other patients, a 40-year-old man and a 28-year-old woman, both undergoing iEEG in the course of epilepsy treatment. In those two volunteers, stimulation of the cingulum bundle also triggered laughter and reduced anxiety with otherwise normal cognition.

Willie notes that the cingulum bundle links many brain areas together. He likens it to a super highway with lots of on and off ramps. He suspects the spot they’ve uncovered lies at a key intersection, providing access to various brain networks regulating mood, emotion, and social interaction.

Previous research has shown that stimulation of other parts of the brain can also prompt patients to laugh. However, what makes stimulation of the cingulum bundle a particularly promising approach is that it not only triggers laughter, but also reduces anxiety.

The new findings suggest that stimulation of the cingulum bundle may be useful for calming patients’ anxieties during neurosurgeries in which they must remain awake. In fact, Willie’s team did so during their 23-year-old woman’s subsequent epilepsy surgery. Each time she became distressed, the stimulation provided immediate relief. Also, if traditional deep brain stimulation or less invasive means of brain stimulation can be developed and found to be safe for long-term use, they may offer new ways to treat depression, anxiety disorders, and/or chronic pain.

Meanwhile, Willie’s team is hard at work using similar approaches to map brain areas involved in other aspects of mood, including fear, sadness, and anxiety. Together with the multidisciplinary work being mounted by the NIH-led BRAIN Initiative, these kinds of studies promise to reveal functionalities of the human brain that have previously been out of reach, with profound consequences for neuroscience and human medicine.

Reference:

[1] Cingulum stimulation enhances positive affect and anxiolysis to facilitate awake craniotomy. Bijanki KR, Manns JR, Inman CS, Choi KS, Harati S, Pedersen NP, Drane DL, Waters AC, Fasano RE, Mayberg HS, Willie JT. J Clin Invest. 2018 Dec 27.

Links:

Video: Patient’s Response (Bijanki et al. The Journal of Clinical Investigation)

Epilepsy Information Page (National Institute of Neurological Disease and Stroke/NIH)

Jon T. Willie (Emory University, Atlanta, GA)

NIH Support: National Institute of Neurological Disease and Stroke; National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences

How the Brain Regulates Vocal Pitch

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Credit: University of California, San Francisco

Whether it’s hitting a high note, delivering a punch line, or reading a bedtime story, the pitch of our voices is a vital part of human communication. Now, as part of their ongoing quest to produce a dynamic picture of neural function in real time, researchers funded by the NIH’s Brain Research through Advancing Innovative Neurotechnologies (BRAIN) Initiative have identified the part of the brain that controls vocal pitch [1].

This improved understanding of how the human brain regulates the pitch of sounds emanating from the voice box, or larynx, is more than cool neuroscience. It could aid in the development of new, more natural-sounding technologies to assist people who have speech disorders or who’ve had their larynxes removed due to injury or disease.