CRISPR/Cas9

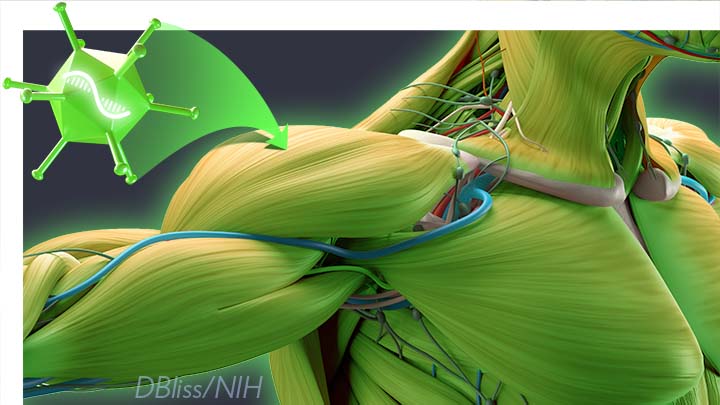

Engineering a Better Way to Deliver Therapeutic Genes to Muscles

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Amid all the progress toward ending the COVID-19 pandemic, it’s worth remembering that researchers here and around the world continue to make important advances in tackling many other serious health conditions. As an inspiring NIH-supported example, I’d like to share an advance on the use of gene therapy for treating genetic diseases that progressively degenerate muscle, such as Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD).

As published recently in the journal Cell, researchers have developed a promising approach to deliver therapeutic genes and gene editing tools to muscle more efficiently, thus requiring lower doses [1]. In animal studies, the new approach has targeted muscle far more effectively than existing strategies. It offers an exciting way forward to reduce unwanted side effects from off-target delivery, which has hampered the development of gene therapy for many conditions.

In boys born with DMD (it’s an X-linked disease and therefore affects males), skeletal and heart muscles progressively weaken due to mutations in a gene encoding a critical muscle protein called dystrophin. By age 10, most boys require a wheelchair. Sadly, their life expectancy remains less than 30 years.

The hope is gene therapies will one day treat or even cure DMD and allow people with the disease to live longer, high-quality lives. Unfortunately, the benign adeno-associated viruses (AAVs) traditionally used to deliver the healthy intact dystrophin gene into cells mostly end up in the liver—not in muscles. It’s also the case for gene therapy of many other muscle-wasting genetic diseases.

The heavy dose of viral vector to the liver is not without concern. Recently and tragically, there have been deaths in a high-dose AAV gene therapy trial for X-linked myotubular myopathy (XLMTM), a different disorder of skeletal muscle in which there may already be underlying liver disease, potentially increasing susceptibility to toxicity.

To correct this concerning routing error, researchers led by Mohammadsharif Tabebordbar in the lab of Pardis Sabeti, Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard and Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, have now assembled an optimized collection of AAVs. They have been refined to be about 10 times better at reaching muscle fibers than those now used in laboratory studies and clinical trials. In fact, researchers call them myotube AAVs, or MyoAAVs.

MyoAAVs can deliver therapeutic genes to muscle at much lower doses—up to 250 times lower than what’s needed with traditional AAVs. While this approach hasn’t yet been tried in people, animal studies show that MyoAAVs also largely avoid the liver, raising the prospect for more effective gene therapies without the risk of liver damage and other serious side effects.

In the Cell paper, the researchers demonstrate how they generated MyoAAVs, starting out with the commonly used AAV9. Their goal was to modify the outer protein shell, or capsid, to create an AAV that would be much better at specifically targeting muscle. To do so, they turned to their capsid engineering platform known as, appropriately enough, DELIVER. It’s short for Directed Evolution of AAV capsids Leveraging In Vivo Expression of transgene RNA.

Here’s how DELIVER works. The researchers generate millions of different AAV capsids by adding random strings of amino acids to the portion of the AAV9 capsid that binds to cells. They inject those modified AAVs into mice and then sequence the RNA from cells in muscle tissue throughout the body. The researchers want to identify AAVs that not only enter muscle cells but that also successfully deliver therapeutic genes into the nucleus to compensate for the damaged version of the gene.

This search delivered not just one AAV—it produced several related ones, all bearing a unique surface structure that enabled them specifically to target muscle cells. Then, in collaboration with Amy Wagers, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, the team tested their MyoAAV toolset in animal studies.

The first cargo, however, wasn’t a gene. It was the gene-editing system CRISPR-Cas9. The team found the MyoAAVs correctly delivered the gene-editing system to muscle cells and also repaired dysfunctional copies of the dystrophin gene better than the CRISPR cargo carried by conventional AAVs. Importantly, the muscles of MyoAAV-treated animals also showed greater strength and function.

Next, the researchers teamed up with Alan Beggs, Boston Children’s Hospital, and found that MyoAAV was effective in treating mouse models of XLMTM. This is the very condition mentioned above, in which very high dose gene therapy with a current AAV vector has led to tragic outcomes. XLMTM mice normally die in 10 weeks. But, after receiving MyoAAV carrying a corrective gene, all six mice had a normal lifespan. By comparison, mice treated in the same way with traditional AAV lived only up to 21 weeks of age. What’s more, the researchers used MyoAAV at a dose 100 times lower than that currently used in clinical trials.

While further study is needed before this approach can be tested in people, MyoAAV was also used to successfully introduce therapeutic genes into human cells in the lab. This suggests that the early success in animals might hold up in people. The approach also has promise for developing AAVs with potential for targeting other organs, thereby possibly providing treatment for a wide range of genetic conditions.

The new findings are the result of a decade of work from Tabebordbar, the study’s first author. His tireless work is also personal. His father has a rare genetic muscle disease that has put him in a wheelchair. With this latest advance, the hope is that the next generation of promising gene therapies might soon make its way to the clinic to help Tabebordbar’s father and so many other people.

Reference:

[1] Directed evolution of a family of AAV capsid variants enabling potent muscle-directed gene delivery across species. Tabebordbar M, Lagerborg KA, Stanton A, King EM, Ye S, Tellez L, Krunnfusz A, Tavakoli S, Widrick JJ, Messemer KA, Troiano EC, Moghadaszadeh B, Peacker BL, Leacock KA, Horwitz N, Beggs AH, Wagers AJ, Sabeti PC. Cell. 2021 Sep 4:S0092-8674(21)01002-3.

Links:

Muscular Dystrophy Information Page (National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke/NIH)

X-linked myotubular myopathy (Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center/National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences/NIH)

Somatic Cell Genome Editing (Common Fund/NIH)

Mohammadsharif Tabebordbar (Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard and Harvard University, Cambridge, MA)

Sabeti Lab (Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard and Harvard University)

NIH Support: Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development; Common Fund

Could CRISPR Gene-Editing Technology Be an Answer to Chronic Pain?

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Gene editing has shown great promise as a non-heritable way to treat a wide range of conditions, including many genetic diseases and more recently, even COVID-19. But could a version of the CRISPR gene-editing tool also help deliver long-lasting pain relief without the risk of addiction associated with prescription opioid drugs?

In work recently published in the journal Science Translational Medicine, researchers demonstrated in mice that a modified version of the CRISPR system can be used to “turn off” a gene in critical neurons to block the transmission of pain signals [1]. While much more study is needed and the approach is still far from being tested in people, the findings suggest that this new CRISPR-based strategy could form the basis for a whole new way to manage chronic pain.

This novel approach to treating chronic pain occurred to Ana Moreno, the study’s first author, when she was a Ph.D. student in the NIH-supported lab of Prashant Mali, University of California, San Diego. Mali had been studying a wide range of novel gene- and cell-based therapeutics. While reading up on both, Moreno landed on a paper about a mutation in a gene that encodes a pain-enhancing protein in spinal neurons called NaV1.7.

Moreno read that kids born with a loss-of-function mutation in this gene have a rare condition known as congenital insensitivity to pain (CIP). They literally don’t sense and respond to pain. Although these children often fail to recognize serious injuries because of the absence of pain to alert them, they have no other noticeable physical effects of the condition.

For Moreno, something clicked. What if it were possible to engineer a new kind of treatment—one designed to turn this gene down or fully off and stop people from feeling chronic pain?

Moreno also had an idea about how to do it. She’d been working on repressing or “turning off” genes using a version of CRISPR known as “dead” Cas9 [2]. In CRISPR systems designed to edit DNA, the Cas9 enzyme is often likened to a pair of scissors. Its job is to cut DNA in just the right spot with the help of an RNA guide. However, CRISPR-dead Cas9 no longer has any ability to cut DNA. It simply sticks to its gene target and blocks its expression. Another advantage is that the system won’t lead to any permanent DNA changes, since any treatment based on CRISPR-dead Cas9 might be safely reversed.

After establishing that the technique worked in cells, Moreno and colleagues moved to studies of laboratory mice. They injected viral vectors carrying the CRISPR treatment into mice with different types of chronic pain, including inflammatory and chemotherapy-induced pain.

Moreno and colleagues determined that all the mice showed evidence of durable pain relief. Remarkably, the treatment also lasted for three months or more and, importantly, without any signs of side effects. The researchers are also exploring another approach to do the same thing using a different set of editing tools called zinc finger nucleases (ZFNs).

The researchers say that one of these approaches might one day work for people with a large number of chronic pain conditions that involve transmission of the pain signal through NaV1.7. That includes diabetic polyneuropathy, sciatica, and osteoarthritis. It also could provide relief for patients undergoing chemotherapy, along with those suffering from many other conditions. Moreno and Mali have co-founded the spinoff company Navega Therapeutics, San Diego, CA, to work on the preclinical steps necessary to help move their approach closer to the clinic.

Chronic pain is a devastating public health problem. While opioids are effective for acute pain, they can do more harm than good for many chronic pain conditions, and they are responsible for a nationwide crisis of addiction and drug overdose deaths [3]. We cannot solve any of these problems without finding new ways to treat chronic pain. As we look to the future, it’s hopeful that innovative new therapeutics such as this gene-editing system could one day help to bring much needed relief.

References:

[1] Long-lasting analgesia via targeted in situ repression of NaV1.7 in mice. Moreno AM, Alemán F, Catroli GF, Hunt M, Hu M, Dailamy A, Pla A, Woller SA, Palmer N, Parekh U, McDonald D, Roberts AJ, Goodwill V, Dryden I, Hevner RF, Delay L, Gonçalves Dos Santos G, Yaksh TL, Mali P. Sci Transl Med. 2021 Mar 10;13(584):eaay9056.

[2] Nuclease dead Cas9 is a programmable roadblock for DNA replication. Whinn KS, Kaur G, Lewis JS, Schauer GD, Mueller SH, Jergic S, Maynard H, Gan ZY, Naganbabu M, Bruchez MP, O’Donnell ME, Dixon NE, van Oijen AM, Ghodke H. Sci Rep. 2019 Sep 16;9(1):13292.

[3] Drug Overdose Deaths. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Links:

Congenital insensitivity to pain (National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences/NIH)

Opioids (National Institute on Drug Abuse/NIH)

Mali Lab (University of California, San Diego)

Navega Therapeutics (San Diego, CA)

NIH Support: National Human Genome Research Institute; National Cancer Institute; National Institute of General Medical Sciences; National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke

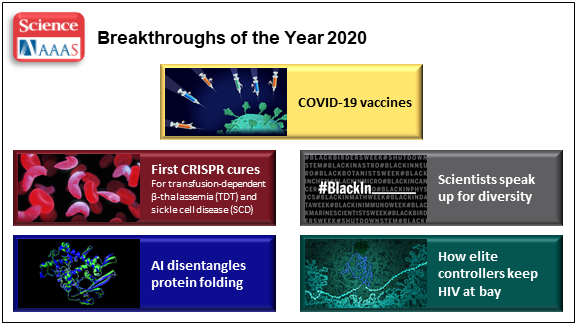

What A Year It Was for Science Advances!

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

At the close of every year, editors and writers at the journal Science review the progress that’s been made in all fields of science—from anthropology to zoology—to select the biggest advance of the past 12 months. In most cases, this Breakthrough of the Year is as tough to predict as the Oscar for Best Picture. Not in 2020. In a year filled with a multitude of challenges posed by the emergence of the deadly coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-2019), the breakthrough was the development of the first vaccines to protect against this pandemic that’s already claimed the lives of more than 360,000 Americans.

In keeping with its annual tradition, Science also selected nine runner-up breakthroughs. This impressive list includes at least three areas that involved efforts supported by NIH: therapeutic applications of gene editing, basic research understanding HIV, and scientists speaking up for diversity. Here’s a quick rundown of all the pioneering advances in biomedical research, both NIH and non-NIH funded:

Shots of Hope. A lot of things happened in 2020 that were unprecedented. At the top of the list was the rapid development of COVID-19 vaccines. Public and private researchers accomplished in 10 months what normally takes about 8 years to produce two vaccines for public use, with more on the way in 2021. In my more than 25 years at NIH, I’ve never encountered such a willingness among researchers to set aside their other concerns and gather around the same table to get the job done fast, safely, and efficiently for the world.

It’s also pretty amazing that the first two conditionally approved vaccines from Pfizer and Moderna were found to be more than 90 percent effective at protecting people from infection with SARS-CoV-2, the coronavirus that causes COVID-19. Both are innovative messenger RNA (mRNA) vaccines, a new approach to vaccination.

For this type of vaccine, the centerpiece is a small, non-infectious snippet of mRNA that encodes the instructions to make the spike protein that crowns the outer surface of SARS-CoV-2. When the mRNA is injected into a shoulder muscle, cells there will follow the encoded instructions and temporarily make copies of this signature viral protein. As the immune system detects these copies, it spurs the production of antibodies and helps the body remember how to fend off SARS-CoV-2 should the real thing be encountered.

It also can’t be understated that both mRNA vaccines—one developed by Pfizer and the other by Moderna in conjunction with NIH’s National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases—were rigorously evaluated in clinical trials. Detailed data were posted online and discussed in all-day meetings of an FDA Advisory Committee, open to the public. In fact, given the high stakes, the level of review probably was more scientifically rigorous than ever.

First CRISPR Cures: One of the most promising areas of research now underway involves gene editing. These tools, still relatively new, hold the potential to fix gene misspellings—and potentially cure—a wide range of genetic diseases that were once to be out of reach. Much of the research focus has centered on CRISPR/Cas9. This highly precise gene-editing system relies on guide RNA molecules to direct a scissor-like Cas9 enzyme to just the right spot in the genome to cut out or correct a disease-causing misspelling.

In late 2020, a team of researchers in the United States and Europe succeeded for the first time in using CRISPR to treat 10 people with sickle cell disease and transfusion-dependent beta thalassemia. As published in the New England Journal of Medicine, several months after this non-heritable treatment, all patients no longer needed frequent blood transfusions and are living pain free [1].

The researchers tested a one-time treatment in which they removed bone marrow from each patient, modified the blood-forming hematopoietic stem cells outside the body using CRISPR, and then reinfused them into the body. To prepare for receiving the corrected cells, patients were given toxic bone marrow ablation therapy, in order to make room for the corrected cells. The result: the modified stem cells were reprogrammed to switch back to making ample amounts of a healthy form of hemoglobin that their bodies produced in the womb. While the treatment is still risky, complex, and prohibitively expensive, this work is an impressive start for more breakthroughs to come using gene editing technologies. NIH, including its Somatic Cell Genome Editing program, continues to push the technology to accelerate progress and make gene editing cures for many disorders simpler and less toxic.

Scientists Speak Up for Diversity: The year 2020 will be remembered not only for COVID-19, but also for the very public and inescapable evidence of the persistence of racial discrimination in the United States. Triggered by the killing of George Floyd and other similar events, Americans were forced to come to grips with the fact that our society does not provide equal opportunity and justice for all. And that applies to the scientific community as well.

Science thrives in safe, diverse, and inclusive research environments. It suffers when racism and bigotry find a home to stifle diversity—and community for all—in the sciences. For the nation’s leading science institutions, there is a place and a calling to encourage diversity in the scientific workplace and provide the resources to let it flourish to everyone’s benefit.

For those of us at NIH, last year’s peaceful protests and hashtags were noticed and taken to heart. That’s one of the many reasons why we will continue to strengthen our commitment to building a culturally diverse, inclusive workplace. For example, we have established the NIH Equity Committee. It allows for the systematic tracking and evaluation of diversity and inclusion metrics for the intramural research program for each NIH institute and center. There is also the recently founded Distinguished Scholars Program, which aims to increase the diversity of tenure track investigators at NIH. Recently, NIH also announced that it will provide support to institutions to recruit diverse groups or “cohorts” of early-stage research faculty and prepare them to thrive as NIH-funded researchers.

AI Disentangles Protein Folding: Proteins, which are the workhorses of the cell, are made up of long, interconnected strings of amino acids that fold into a wide variety of 3D shapes. Understanding the precise shape of a protein facilitates efforts to figure out its function, its potential role in a disease, and even how to target it with therapies. To gain such understanding, researchers often try to predict a protein’s precise 3D chemical structure using basic principles of physics—including quantum mechanics. But while nature does this in real time zillions of times a day, computational approaches have not been able to do this—until now.

Of the roughly 170,000 proteins mapped so far, most have had their structures deciphered using powerful imaging techniques such as x-ray crystallography and cryo–electron microscopy (cryo-EM). But researchers estimate that there are at least 200 million proteins in nature, and, as amazing as these imaging techniques are, they are laborious, and it can take many months or years to solve 3D structure of a single protein. So, a breakthrough certainly was needed!

In 2020, researchers with the company Deep Mind, London, developed an artificial intelligence (AI) program that rapidly predicts most protein structures as accurately as x-ray crystallography and cryo-EM can map them [2]. The AI program, called AlphaFold, predicts a protein’s structure by computationally modeling the amino acid interactions that govern its 3D shape.

Getting there wasn’t easy. While a complete de novo calculation of protein structure still seemed out of reach, investigators reasoned that they could kick start the modeling if known structures were provided as a training set to the AI program. Utilizing a computer network built around 128 machine learning processors, the AlphaFold system was created by first focusing on the 170,000 proteins with known structures in a reiterative process called deep learning. The process, which is inspired by the way neural networks in the human brain process information, enables computers to look for patterns in large collections of data. In this case, AlphaFold learned to predict the underlying physical structure of a protein within a matter of days. This breakthrough has the potential to accelerate the fields of structural biology and protein research, fueling progress throughout the sciences.

How Elite Controllers Keep HIV at Bay: The term “elite controller” might make some people think of video game whizzes. But here, it refers to the less than 1 percent of people living with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) who’ve somehow stayed healthy for years without taking antiretroviral drugs. In 2020, a team of NIH-supported researchers figured out why this is so.

In a study of 64 elite controllers, published in the journal Nature, the team discovered a link between their good health and where the virus has inserted itself in their genomes [3]. When a cell transcribes a gene where HIV has settled, this so-called “provirus,” can produce more virus to infect other cells. But if it settles in a part of a chromosome that rarely gets transcribed, sometimes called a gene desert, the provirus is stuck with no way to replicate. Although this discovery won’t cure HIV/AIDS, it points to a new direction for developing better treatment strategies.

In closing, 2020 presented more than its share of personal and social challenges. Among those challenges was a flood of misinformation about COVID-19 that confused and divided many communities and even families. That’s why the editors and writers at Science singled out “a second pandemic of misinformation” as its Breakdown of the Year. This divisiveness should concern all of us greatly, as COVID-19 cases continue to soar around the country and our healthcare gets stretched to the breaking point. I hope and pray that we will all find a way to come together, both in science and in society, as we move forward in 2021.

References:

[1] CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing for sickle cell disease and β-thalassemia. Frangoul H et al. N Engl J Med. 2020 Dec 5.

[2] ‘The game has changed.’ AI triumphs at protein folding. Service RF. Science. 04 Dec 2020.

[3] Distinct viral reservoirs in individuals with spontaneous control of HIV-1. Jiang C et al. Nature. 2020 Sep;585(7824):261-267.

Links:

COVID-19 Research (NIH)

2020 Science Breakthrough of the Year (American Association for the Advancement of Science, Washington, D.C)

Gene-Editing Advance Puts More Gene-Based Cures Within Reach

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

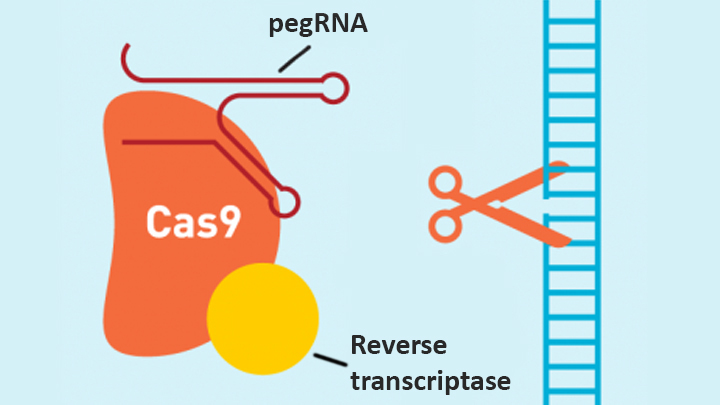

There’s been tremendous excitement recently about the potential of CRISPR and related gene-editing technologies for treating or even curing sickle cell disease (SCD), muscular dystrophy, HIV, and a wide range of other devastating conditions. Now comes word of another remarkable advance—called “prime editing”—that may bring us even closer to reaching that goal.

As groundbreaking as CRISPR/Cas9 has been for editing specific genes, the system has its limitations. The initial version is best suited for making a double-stranded break in DNA, followed by error-prone repair. The outcome is generally to knock out the target. That’s great if eliminating the target is the desired goal. But what if the goal is to fix a mutation by editing it back to the normal sequence?

The new prime editing system, which was described recently by NIH-funded researchers in the journal Nature, is revolutionary because it offers much greater control for making a wide range of precisely targeted edits to the DNA code, which consists of the four “letters” (actually chemical bases) A, C, G, and T [1].

Already, in tests involving human cells grown in the lab, the researchers have used prime editing to correct genetic mutations that cause two inherited diseases: SCD, a painful, life-threatening blood disorder, and Tay-Sachs disease, a fatal neurological disorder. What’s more, they say the versatility of their new gene-editing system means it can, in principle, correct about 89 percent of the more than 75,000 known genetic variants associated with human diseases.

In standard CRISPR, a scissor-like enzyme called Cas9 is used to cut all the way through both strands of the DNA molecule’s double helix. That usually results in the cell’s DNA repair apparatus inserting or deleting DNA letters at the site. As a result, CRISPR is extremely useful for disrupting genes and inserting or removing large DNA segments. However, it is difficult to use this system to make more subtle corrections to DNA, such as swapping a letter T for an A.

To expand the gene-editing toolbox, a research team led by David R. Liu, Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard, Cambridge, MA, previously developed a class of editing agents called base editors [2,3]. Instead of cutting DNA, base editors directly convert one DNA letter to another. However, base editing has limitations, too. It works well for correcting four of the most common single letter mutations in DNA. But at least so far, base editors haven’t been able to make eight other single letter changes, or fix extra or missing DNA letters.

In contrast, the new prime editing system can precisely and efficiently swap any single letter of DNA for any other, and can make both deletions and insertions, at least up to a certain size. The system consists of a modified version of the Cas9 enzyme fused with another enzyme, called reverse transcriptase, and a specially engineered guide RNA, called pegRNA. The latter contains the desired gene edit and steers the needed editing apparatus to a specific site in a cell’s DNA.

Once at the site, the Cas9 nicks one strand of the double helix. Then, reverse transcriptase uses one DNA strand to “prime,” or initiate, the letter-by-letter transfer of new genetic information encoded in the pegRNA into the nicked spot, much like the search-and-replace function of word processing software. The process is then wrapped up when the prime editing system prompts the cell to remake the other DNA strand to match the new genetic information.

So far, in tests involving human cells grown in a lab dish, Liu and his colleagues have used prime editing to correct the most common mutation that causes SCD, converting a T to an A. They were also able to remove four DNA letters to correct the most common mutation underlying Tay-Sachs disease, a devastating condition that typically produces symptoms in children within the first year and leads to death by age four. The researchers also used their new system to insert new DNA segments up to 44 letters long and to remove segments at least 80 letters long.

Prime editing does have certain limitations. For example, 11 percent of known disease-causing variants result from changes in the number of gene copies, and it’s unclear if prime editing can insert or remove DNA that’s the size of full-length genes—which may contain up to 2.4 million letters.

It’s also worth noting that now-standard CRISPR editing and base editors have been tested far more thoroughly than prime editing in many different kinds of cells and animal models. These earlier editing technologies also may be more efficient for some purposes, so they will likely continue to play unique and useful roles in biomedicine.

As for prime editing, additional research is needed before we can consider launching human clinical trials. Among the areas that must be explored are this technology’s safety and efficacy in a wide range of cell types, and its potential for precisely and safely editing genes in targeted tissues within living animals and people.

Meanwhile, building on all these bold advances, efforts are already underway to accelerate the development of affordable, accessible gene-based cures for SCD and HIV on a global scale. Just last month, NIH and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation announced a collaboration that will invest at least $200 million over the next four years toward this goal. Last week, I had the chance to present this plan and discuss it with global health experts at the Grand Challenges meeting Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. The project is an unprecedented partnership designed to meet an unprecedented opportunity to address health conditions that once seemed out of reach but—as this new work helps to show—may now be within our grasp.

References:

[1] Search-and-replace genome editing without double-strand breaks or donor DNA. Anzalone AV, Randolph PB, Davis JR, Sousa AA, Koblan LW, Levy JM, Chen PJ, Wilson C, Newby GA, Raguram A, Liu DR. Nature. Online 2019 October 21. [Epub ahead of print]

[2] Programmable editing of a target base in genomic DNA without double-stranded DNA cleavage. Komor AC, Kim YB, Packer MS, Zuris JA, Liu DR. Nature. 2016 May 19;533(7603):420-424.

[3] Programmable base editing of A•T to G•C in genomic DNA without DNA cleavage. Gaudelli NM, Komor AC, Rees HA, Packer MS, Badran AH, Bryson DI, Liu DR. Nature. 2017 Nov 23;551(7681):464-471.

Links:

Tay-Sachs Disease (Genetics Home Reference/National Library of Medicine/NIH)

Sickle Cell Disease (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute/NIH)

Cure Sickle Cell Initiative (NHLBI)

What are Genome Editing and CRISPR-Cas9? (National Library of Medicine/NIH)

Somatic Cell Genome Editing Program (Common Fund/NIH)

David R. Liu (Harvard, Cambridge, MA)

NIH Support: National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases; National Human Genome Research Institute; National Institute for General Medical Sciences; National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering; National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences

Nano-Sized Solution for Efficient and Versatile CRISPR Gene Editing

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Credit: Guojun Chen and Amr Abdeen, University of Wisconsin-Madison

If used to make non-heritable genetic changes, CRISPR gene-editing technology holds tremendous promise for treating or curing a wide range of devastating disorders, including sickle cell disease, vision loss, and muscular dystrophy. Early efforts to deliver CRISPR-based therapies to affected tissues in a patient’s body typically have involved packing the gene-editing tools into viral vectors, which may cause unwanted immune reactions and other adverse effects.

Now, NIH-supported researchers have developed an alternative CRISPR delivery system: nanocapsules. Not only do these tiny, synthetic capsules appear to pose a lower risk of side effects, they can be precisely customized to deliver their gene-editing payloads to many different types of cells or tissues in the body, which can be extremely tough to do with a virus. Another advantage of these gene-editing nanocapsules is that they can be freeze-dried into a powder that’s easier than viral systems to transport, store, and administer at different doses.

In findings published in Nature Nanotechnology [1], researchers, led by Shaoqin Gong and Krishanu Saha, University of Wisconsin-Madison, developed the nanocapsules with specific design criteria in mind. They would need to be extremely small, about the size of a small virus, for easy entry into cells. Their surface would need to be adaptable for targeting different cell types. They also had to be highly stable in the bloodstream and yet easily degraded to release their contents once inside a cell.

After much hard work in the lab, they created their prototype. It features a thin polymer shell that’s easily decorated with peptides or other ingredients to target the nanocapsule to a predetermined cell type.

At just 25 nanometers in diameter, each nanocapsule still has room to carry cargo. That cargo includes a single CRISPR/Cas9 scissor-like enzyme for snipping DNA and a guide RNA that directs it to the right spot in the genome for editing.

In the bloodstream, the nanocapsules remain fully intact. But, once inside a cell, their polymer shells quickly disintegrate and release the gene-editing payload. How is this possible? The crosslinking molecules that hold the polymer together immediately degrade in the presence of another molecule, called glutathione, which is found at high levels inside cells.

The studies showed that human cells grown in the lab readily engulf and take the gene-editing nanocapsules into bubble-like endosomes. Their gene-editing contents are then released into the cytoplasm where they can begin making their way to a cell’s nucleus within a few hours.

Further study in lab dishes showed that nanocapsule delivery of CRISPR led to precise gene editing of up to about 80 percent of human cells with little sign of toxicity. The gene-editing nanocapsules also retained their potency even after they were freeze-dried and reconstituted.

But would the nanocapsules work in a living system? To find out, the researchers turned to mice, targeting their nanocapsules to skeletal muscle and tissue in the retina at the back of eye. Their studies showed that nanocapsules injected into muscle or the tight subretinal space led to efficient gene editing. In the eye, the nanocapsules worked especially well in editing retinal cells when they were decorated with a chemical ingredient known to bind an important retinal protein.

Based on their initial results, the researchers anticipate that their delivery system could reach most cells and tissues for virtually any gene-editing application. In fact, they are now exploring the potential of their nanocapsules for editing genes within brain tissue.

I’m also pleased to note that Gong and Saha’s team is part of a nationwide consortium on genome editing supported by NIH’s recently launched Somatic Cell Genome Editing program. This program is dedicated to translating breakthroughs in gene editing into treatments for as many genetic diseases as possible. So, we can all look forward to many more advances like this one.

Reference:

[1] A biodegradable nanocapsule delivers a Cas9 ribonucleoprotein complex for in vivo genome editing. Chen G, Abdeen AA, Wang Y, Shahi PK, Robertson S, Xie R, Suzuki M, Pattnaik BR, Saha K, Gong S. Nat Nanotechnol. 2019 Sep 9.

Links:

Somatic Cell Genome Editing (NIH)

Saha Lab (University of Wisconsin-Madison)

Shaoqin (Sarah) Gong (University of Wisconsin-Madison)

NIH Support: National Eye Institute; National Institute of General Medical Sciences; National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; Common Fund

Study in Africa Yields New Diabetes Gene

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

When I volunteered to serve as a physician at a hospital in rural Nigeria more than 25 years ago, I expected to treat a lot of folks with infectious diseases, such as malaria and tuberculosis. And that certainly happened. What I didn’t expect was how many people needed care for type 2 diabetes (T2D) and the health problems it causes. Surprisingly, these individuals were generally not overweight, and the course of their illness seemed different than in the West.

The experience inspired me to join with other colleagues at Howard University, Washington, DC, to help found the Africa America Diabetes Mellitus (AADM) study. It aims to uncover genomic risk factors for T2D in Africa and, using that information, improve understanding of the condition around the world.

So, I’m pleased to report that, using genomic data from more than 5,000 volunteers, our AADM team recently discovered a new gene, called ZRANB3, that harbors a variant associated with T2D in sub-Saharan Africa [1]. Using sophisticated laboratory models, the team showed that a malfunctioning ZRANB3 gene impairs insulin production to control glucose levels in the bloodstream.

Since my first trip to Nigeria, the number of people with T2D has continued to rise. It’s now estimated that about 8 to 10 percent of Nigerians have some form of diabetes [2]. In Africa, diabetes affects more than 7 percent of the population, more than twice the incidence in 1980 [3].

The causes of T2D involve a complex interplay of genetic, environmental, and lifestyle factors. I was particularly interested in finding out whether the genetic factors for T2D might be different in sub-Saharan Africa than in the West. But at the time, there was a dearth of genomic information about T2D in Africa, the cradle of humanity. To understand complex diseases like T2D fully, we need all peoples and continents represented in the research.

To begin to fill this research gap, the AADM team got underway and hasn’t looked back. In the latest study, led by Charles Rotimi at NIH’s National Human Genome Research Institute, in partnership with multiple African diabetes experts, the AADM team enlisted 5,231 volunteers from Nigeria, Ghana, and Kenya. About half of the study’s participants had T2D and half did not.

As reported in Nature Communications, their genome-wide search for T2D gene variants turned up three interesting finds. Two were in genes previously linked to T2D risk in other human populations. The third involved a gene that codes for ZRANB3, an enzyme associated with DNA replication and repair that had never been reported in association with T2D.

To understand how ZRANB3 might influence a person’s risk for developing T2D, the researchers turned to zebrafish (Danio rerio), an excellent vertebrate model for its rapid development. The researchers found that the ZRANB3 gene is active in insulin-producing beta cells of the pancreas. That was important to know because people with T2D frequently have reduced numbers of beta cells, which compromises their ability to produce enough insulin.

The team next used CRISPR/Cas9 gene-editing tools either to “knock out” or reduce the expression of ZRANB3 in young zebrafish. In both cases, it led to increased loss of beta cells.

Additional study in the beta cells of mice provided more details. While normal beta cells released insulin in response to high levels of glucose, those with suppressed ZRANB3 activity couldn’t. Together, the findings show that ZRANB3 is important for beta cells to survive and function normally. It stands to reason, then, that people with a lower functioning variant of ZRANB3 would be more susceptible to T2D.

In many cases, T2D can be managed with some combination of diet, exercise, and oral medications. But some people require insulin to manage the disease. The new findings suggest, particularly for people of African ancestry, that the variant of the ZRANB3 gene that one inherits might help to explain those differences. People carrying particular variants of this gene also may benefit from beginning insulin treatment earlier, before their beta cells have been depleted.

So why wasn’t ZRANB3 discovered in the many studies on T2D carried out in the United States, Europe, and Asia? It turns out that the variant that predisposes Africans to this disease is extremely rare in these other populations. Only by studying Africans could this insight be uncovered.

More than 20 years ago, I helped to start the AADM project to learn more about the genetic factors driving T2D in sub-Saharan Africa. Other dedicated AADM leaders have continued to build the research project, taking advantage of new technologies as they came along. It’s profoundly gratifying that this project has uncovered such an impressive new lead, revealing important aspects of human biology that otherwise would have been missed. The AADM team continues to enroll volunteers, and the coming years should bring even more discoveries about the genetic factors that contribute to T2D.

References:

[1] ZRANB3 is an African-specific type 2 diabetes locus associated with beta-cell mass and insulin response. Adeyemo AA, Zaghloul NA, Chen G, Doumatey AP, Leitch CC, Hostelley TL, Nesmith JE, Zhou J, Bentley AR, Shriner D, Fasanmade O, Okafor G, Eghan B Jr, Agyenim-Boateng K, Chandrasekharappa S, Adeleye J, Balogun W, Owusu S, Amoah A, Acheampong J, Johnson T, Oli J, Adebamowo C; South Africa Zulu Type 2 Diabetes Case-Control Study, Collins F, Dunston G, Rotimi CN. Nat Commun. 2019 Jul 19;10(1):3195.

[2] Diabetes mellitus in Nigeria: The past, present and future. Ogbera AO, Ekpebegh C. World J Diabetes. 2014 Dec 15;5(6):905-911.

[3] Global report on diabetes. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2016. World Health Organization.

Links:

Diabetes (National Institute of Diabetes ad Digestive and Kidney Diseases/NIH)

Diabetes and African Americans (Department of Health and Human Services)

Why Use Zebrafish to Study Human Diseases (Intramural Research Program/NIH)

Charles Rotimi (National Human Genome Research Institute/NIH)

NIH Support: National Human Genome Research Institute; National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities

A CRISPR Approach to Treating Sickle Cell

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Recently, CBS’s “60 Minutes” highlighted the story of Jennelle Stephenson, a brave young woman with sickle cell disease (SCD). Jennelle now appears potentially cured of this devastating condition, thanks to an experimental gene therapy being tested at the NIH Clinical Center in Bethesda, MD. As groundbreaking as this research may be, it’s among a variety of innovative strategies now being tried to cure SCD and other genetic diseases that have long seemed out of reach.

One particularly exciting approach involves using gene editing to increase levels of fetal hemoglobin (HbF) in the red blood cells of people with SCD. Shortly after birth, babies usually stop producing HbF, and switch over to the adult form of hemoglobin. But rare individuals continue to make high levels of HbF throughout their lives. This is referred to as hereditary persistence of fetal hemoglobin (HPFH). (My own postdoctoral research in the early 1980s discovered some of the naturally occurring DNA mutations that lead to this condition.)

Individuals with HPFH are entirely healthy. Strikingly, rare individuals with SCD who also have HPFH have an extremely mild version of sickle cell disease—essentially the presence of significant quantities of HbF provides protection against sickling. So, researchers have been exploring ways to boost HbF in everyone with SCD—and gene editing may provide an effective, long-lasting way to do this.

Clinical trials of this approach are already underway. And new findings reported in Nature Medicine show it may be possible to make the desired edits even more efficiently, raising the possibility that a single infusion of gene-edited cells might be able to cure SCD [1].

Sickle cell disease is caused by a specific point mutation in a gene that codes for the beta chain of hemoglobin. People with just one copy of this mutation have sickle cell trait and are generally healthy. But those who inherit two mutant copies of this gene suffer lifelong consequences of the presence of this abnormal protein. Their red blood cells—normally flexible and donut-shaped—assume the sickled shape that gives SCD its name. The sickled cells clump together and stick in small blood vessels, resulting in severe pain, anemia, stroke, pulmonary hypertension, organ failure, and far too often, early death.

Eleven years ago, a team led by Vijay Sankaran and Stuart Orkin at Boston Children’s Hospital and the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute discovered that a protein called BCL11A seemed to determine HbF levels [2]. Subsequent work showed the protein actually works as a master mediator of the switch from fetal to adult hemoglobin, which normally occurs shortly after birth.

Five years ago, Orkin and Daniel Bauer identified a specific enhancer of BCL11A expression that could be an attractive target for gene editing [3]. They could knock out the enhancer in the bone marrow, and BCL11A would not be produced, allowing HbF to stay switched on.

Because the BCL11A protein is required to turn off production of HbF in red cells. the researchers had another idea. They thought it might be possible to keep HbF on permanently by disrupting BCL11A in blood-forming hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs). The hope was that such a treatment might offer people with SCD a permanent supply of healthy red blood cells.

Fast-forward to the present, and researchers are now testing the ability of gene editing tools to cure the disease. A favorite editing system is CRISPR, which I’ve highlighted on my blog.

CRISPR is a highly precise gene-editing tool that relies on guide RNA molecules to direct a scissor-like Cas9 enzyme to just the right spot in the genome to correct the misspelling. The gene-editing treatment involves removing bone marrow from a patient, modifying the HSCs outside the body using CRISPR gene-editing tools, and then returning them back to the patient. Preclinical studies had shown that CRISPR can be effective in editing BCL11A to boost HbF production.

But questions lingered about the editing efficiency in HSCs versus more common, shorter-lived progenitor cells found in bone marrow samples. The efficiency greatly influences how long the edited cells might benefit patients. Bauer’s team saw room for improvement and, as the new study shows, they were right.

To produce lasting HbF production, it’s important to edit as many HSCs as possible. But it turns out that HSCs are more resistant to editing than other types of cells in bone marrow. With a series of adjustments to the gene-editing protocol, including use of an optimized version of the Cas9 protein, the researchers showed they could push the number of edited genes from about 80 percent to about 95 percent.

Their studies show that the most frequent Cas9 edits in HSCs are tiny insertions of a single DNA “letter.” With that slight edit to the BCL11A gene, HSCs reprogram themselves in a way that ensures long-term HbF production.

As a first test of their CRISPR-edited human HSCs, the researchers carried out the editing on HSCs derived from patients with SCD. Then they transferred the editing cells into immune-compromised mice. Four months later, the mice continued to produce red blood cells that produced high levels of HbF and resisted sickling. Bauer says they’re already taking steps to begin testing cells edited with their optimized protocol in a clinical trial.

What’s truly exciting is that the first U.S. human clinical trials of such a gene-editing approach for SCD are already underway, led by CRISPR Therapeutics/Vertex Pharmaceuticals and Sangamo Therapeutics/Sanofi. In January, CRISPR Therapeutics/Vertex Pharmaceuticals announced that the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) had granted Fast Track Designation for their CRISPR-based treatment called CTX001 [4].

In that recent “60 Minutes” segment, I dared to suggest that we now have what looks like a cure for SCD. As shown by this new work and the clinical trials underway, we in fact may soon have multiple different strategies to provide cures for this devastating disease. And if this can work for sickle cell, a similar strategy might work for other genetic conditions that currently lack any effective treatment.

References:

[1] Highly efficient therapeutic gene editing of human hematopoietic stem cells. Wu Y, Zeng J, Roscoe BP, Liu P, Yao Q, Lazzarotto CR, Clement K, Cole MA, Luk K, Baricordi C, Shen AH, Ren C, Esrick EB, Manis JP, Dorfman DM, Williams DA, Biffi A, Brugnara C, Biasco L, Brendel C, Pinello L, Tsai SQ, Wolfe SA, Bauer DE. Nat Med. 2019 Mar 25.

[2] Human fetal hemoglobin expression is regulated by the developmental stage-specific repressor BCL11A. Sankaran VG, Menne TF, Xu J, Akie TE, Lettre G, Van Handel B, Mikkola HK, Hirschhorn JN, Cantor AB, Orkin SH.Science. 2008 Dec 19;322(5909):1839-1842.

[3] An erythroid enhancer of BCL11A subject to genetic variation determines fetal hemoglobin level. Bauer DE, Kamran SC, Lessard S, Xu J, Fujiwara Y, Lin C, Shao Z, Canver MC, Smith EC, Pinello L, Sabo PJ, Vierstra J, Voit RA, Yuan GC, Porteus MH, Stamatoyannopoulos JA, Lettre G, Orkin SH. Science. 2013 Oct 11;342(6155):253-257.

[4] CRISPR Therapeutics and Vertex Announce FDA Fast Track Designation for CTX001 for the Treatment of Sickle Cell Disease, CRISPR Therapeutics News Release, Jan. 4, 2019.

Links:

Sickle Cell Disease (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute/NIH)

Cure Sickle Cell Initiative (NHLBI)

What are Genome Editing and CRISPR-Cas9? (National Library of Medicine/NIH)

Could Gene Therapy Cure Sickle Cell Anemia? (CBS News)

Daniel Bauer (Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston)

Somatic Cell Genome Editing Program (Common Fund/NIH)

NIH Support: National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; National Institute of General Medical Sciences; National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases; National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases

Next Page