nanotechnology

Nanoparticle Technology Holds Promise for Protecting Against Many Coronavirus Strains at Once

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

It’s truly encouraging to witness people all across our nation rolling up their sleeves to get their COVID-19 vaccines. That is our best chance to end this pandemic. But this is the third coronavirus to emerge and cause serious human illness in the last 20 years, and it’s probably not the last. So, this is also an opportunity to step up our efforts to develop vaccines to combat future strains of disease-causing coronavirus. With this in mind, I’m heartened by a new NIH-funded study showing the potential of a remarkably adaptable, nanoparticle-based approach to coronavirus vaccine development [1].

Both COVID-19 vaccines currently authorized for human use by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) work by using mRNA to instruct our cells to make an essential portion of the spike protein of SARS-CoV-2, which is the novel coronavirus that causes COVID-19. As our immune system learns to recognize this protein fragment as foreign, it produces antibodies to attack SARS-CoV-2 and prevent COVID-19. What makes the new vaccine technology so powerful is that it raises the possibility of training the immune system to recognize not just one strain of coronavirus—but up to eight—with a single shot.

This approach has not yet been tested in people, but when a research team, led by Pamela Bjorkman, California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, injected this new type of vaccine into mice, it spurred the production of antibodies that react to a variety of different coronaviruses. In fact, some of the mouse antibodies proved to be reactive to related strains of coronavirus that weren’t even represented in the vaccine. These findings suggest that if presented with multiple different fragments of the spike protein’s receptor binding domain (RBD), which is what SARS-like coronaviruses use to infect human cells, the immune system may learn to recognize common features that might protect against as-yet unknown, newly emerging coronaviruses.

This new work, published in the journal Science, utilizes a technology called a mosaic nanoparticle vaccine platform [1]. Originally developed by collaborators at the University of Oxford, United Kingdom, the nanoparticle component of the platform is a “cage” made up of 60 identical proteins. Each of those proteins has a small protein tag that functions much like a piece of Velcro®. In their SARS-CoV-2 work, Bjorkman and her colleagues, including graduate student Alex A. Cohen, engineered multiple different fragments of the spike protein so each had its own Velcro-like tag. When mixed with the nanoparticle, the spike protein fragments stuck to the cage, resulting in a vaccine nanoparticle with spikes representing four to eight distinct coronavirus strains on its surface. In this instance, the researchers chose spike protein fragments from several different strains of SARS-CoV-2, as well as from other related bat coronaviruses thought to pose a threat to humans.

The researchers then injected the vaccine nanoparticles into mice and the results were encouraging. After inoculation, the mice began producing antibodies that could neutralize many different strains of coronavirus. In fact, while more study is needed to understand the mechanisms, the antibodies responded to coronavirus strains that weren’t even represented on the mosaic nanoparticle. Importantly, this broad antibody response came without apparent loss in the antibodies’ ability to respond to any one particular coronavirus strain.

The findings raise the exciting possibility that this new vaccine technology could provide protection against many coronavirus strains with a single shot. Of course, far more study is needed to explore how well such vaccines work to protect animals against infection, and whether they will prove to be safe and effective in people. There will also be significant challenges in scaling up manufacturing. Our goal is not to replace the mRNA COVID-19 vaccines that scientists developed at such a remarkable pace over the last year, but to provide much-needed vaccine strategies and tools to respond swiftly to the emerging coronavirus strains of the future.

As we double down on efforts to combat COVID-19, we must also come to grips with the fact that SARS-CoV-2 isn’t the first—and surely won’t be the last—novel coronavirus to cause disease in humans. With continued research and development of new technologies such as this one, the hope is that we will come out of this terrible pandemic better prepared for future infectious disease threats.

References:

[1] Mosaic RBD nanoparticles elicit neutralizing antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 and zoonotic coronaviruses. Cohen AA, Gnanapragasam PNP, Lee YE, Hoffman PR, Ou S, Kakutani LM, Keeffe JR, Barnes CO, Nussenzweig MC, Bjorkman PJ. Science. 2021 Jan 12.

Links:

COVID-19 Research (NIH)

Bjorkman Lab (California Institute of Technology, Pasadena)

NIH Support: National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases

Nano-Sized Solution for Efficient and Versatile CRISPR Gene Editing

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Credit: Guojun Chen and Amr Abdeen, University of Wisconsin-Madison

If used to make non-heritable genetic changes, CRISPR gene-editing technology holds tremendous promise for treating or curing a wide range of devastating disorders, including sickle cell disease, vision loss, and muscular dystrophy. Early efforts to deliver CRISPR-based therapies to affected tissues in a patient’s body typically have involved packing the gene-editing tools into viral vectors, which may cause unwanted immune reactions and other adverse effects.

Now, NIH-supported researchers have developed an alternative CRISPR delivery system: nanocapsules. Not only do these tiny, synthetic capsules appear to pose a lower risk of side effects, they can be precisely customized to deliver their gene-editing payloads to many different types of cells or tissues in the body, which can be extremely tough to do with a virus. Another advantage of these gene-editing nanocapsules is that they can be freeze-dried into a powder that’s easier than viral systems to transport, store, and administer at different doses.

In findings published in Nature Nanotechnology [1], researchers, led by Shaoqin Gong and Krishanu Saha, University of Wisconsin-Madison, developed the nanocapsules with specific design criteria in mind. They would need to be extremely small, about the size of a small virus, for easy entry into cells. Their surface would need to be adaptable for targeting different cell types. They also had to be highly stable in the bloodstream and yet easily degraded to release their contents once inside a cell.

After much hard work in the lab, they created their prototype. It features a thin polymer shell that’s easily decorated with peptides or other ingredients to target the nanocapsule to a predetermined cell type.

At just 25 nanometers in diameter, each nanocapsule still has room to carry cargo. That cargo includes a single CRISPR/Cas9 scissor-like enzyme for snipping DNA and a guide RNA that directs it to the right spot in the genome for editing.

In the bloodstream, the nanocapsules remain fully intact. But, once inside a cell, their polymer shells quickly disintegrate and release the gene-editing payload. How is this possible? The crosslinking molecules that hold the polymer together immediately degrade in the presence of another molecule, called glutathione, which is found at high levels inside cells.

The studies showed that human cells grown in the lab readily engulf and take the gene-editing nanocapsules into bubble-like endosomes. Their gene-editing contents are then released into the cytoplasm where they can begin making their way to a cell’s nucleus within a few hours.

Further study in lab dishes showed that nanocapsule delivery of CRISPR led to precise gene editing of up to about 80 percent of human cells with little sign of toxicity. The gene-editing nanocapsules also retained their potency even after they were freeze-dried and reconstituted.

But would the nanocapsules work in a living system? To find out, the researchers turned to mice, targeting their nanocapsules to skeletal muscle and tissue in the retina at the back of eye. Their studies showed that nanocapsules injected into muscle or the tight subretinal space led to efficient gene editing. In the eye, the nanocapsules worked especially well in editing retinal cells when they were decorated with a chemical ingredient known to bind an important retinal protein.

Based on their initial results, the researchers anticipate that their delivery system could reach most cells and tissues for virtually any gene-editing application. In fact, they are now exploring the potential of their nanocapsules for editing genes within brain tissue.

I’m also pleased to note that Gong and Saha’s team is part of a nationwide consortium on genome editing supported by NIH’s recently launched Somatic Cell Genome Editing program. This program is dedicated to translating breakthroughs in gene editing into treatments for as many genetic diseases as possible. So, we can all look forward to many more advances like this one.

Reference:

[1] A biodegradable nanocapsule delivers a Cas9 ribonucleoprotein complex for in vivo genome editing. Chen G, Abdeen AA, Wang Y, Shahi PK, Robertson S, Xie R, Suzuki M, Pattnaik BR, Saha K, Gong S. Nat Nanotechnol. 2019 Sep 9.

Links:

Somatic Cell Genome Editing (NIH)

Saha Lab (University of Wisconsin-Madison)

Shaoqin (Sarah) Gong (University of Wisconsin-Madison)

NIH Support: National Eye Institute; National Institute of General Medical Sciences; National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; Common Fund

Teaming Magnetic Bacteria with Nanoparticles for Better Drug Delivery

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Nanoparticles hold great promise for delivering next-generation therapeutics, including those based on CRISPR gene editing tools. The challenge is how to guide these tiny particles through the bloodstream and into the right target tissues. Now, scientists are enlisting some surprising partners in this quest: magnetic bacteria!

First a bit of background. Discovered in the 1960s during studies of bog sediments, “magnetotactic” bacteria contain magnetic, iron-rich particles that enable them to orient themselves to the Earth’s magnetic fields. To explore the potential of these microbes for targeted delivery of nanoparticles, the NIH-funded researchers devised the ingenious system you see in this fluorescence microscopy video. This system features a model blood vessel filled with a liquid that contains both fluorescently-tagged nanoparticles (red) and large swarms of a type of magnetic bacteria called Magnetospirillum magneticum (not visible).

At the touch of a button that rotates external magnetic fields, researchers can wirelessly control the direction in which the bacteria move through the liquid—up, down, left, right, and even “freestyle.” And—get this—the flow created by the synchronized swimming of all these bacteria pushes along any nearby nanoparticles in the same direction, even without any physical contact between the two. In fact, the researchers have found that this bacteria-guided system delivers nanoparticles into target model tissues three times faster than a similar system lacking such bacteria.

How did anyone ever dream this up? Most previous attempts to get nanoparticle-based therapies into diseased tissues have relied on simple diffusion or molecular targeting methods. Because those approaches are not always ideal, NIH-funded researchers Sangeeta Bhatia, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA, and Simone Schürle, formerly of MIT and now ETH Zurich, asked themselves: Could magnetic forces be used to propel nanoparticles through the bloodstream?

As a graduate student at ETH Zurich, Schürle had worked to develop and study tiny magnetic robots, each about the size of a cell. Those microbots, called artificial bacterial flagella (ABF), were designed to replicate the movements of bacteria, relying on miniature flagellum-like propellers to move them along in corkscrew-like fashion.

In a study published recently in Science Advances, the researchers found that the miniature robots worked as hoped in tests within a model blood vessel [1]. Using magnets to propel a single microbot, the researchers found that 200-nanometer-sized polystyrene balls penetrated twice as far into a model tissue as they did without the aid of the magnet-driven forces.

At the same time, others in the Bhatia lab were developing bacteria that could be used to deliver cancer-fighting drugs. Schürle and Bhatia wished they could direct those microbial swarms using magnets as they could with the microbots. That’s when they learned about the potential of M. magneticum and developed the experimental system demonstrated in the video above.

The researchers’ next step will be to test their magnetic approach to drug delivery in a mouse model. Ultimately, they think their innovative strategy holds promise for delivering nanoparticles carrying a wide range of therapeutic payloads right to a tumor, infection, or other diseased tissue. It’s yet another example of how basic research combined with outside-the-box thinking can lead to surprisingly creative solutions with real potential to improve human health.

References:

[1] Synthetic and living micropropellers for convection-enhanced nanoparticle transport. Schürle S, Soleimany AP, Yeh T, Anand GM, Häberli M, Fleming HE, Mirkhani N, Qiu F, Hauert S, Wang X, Nelson BJ, Bhatia SN. Sci Adv. 2019 Apr 26;5(4):eaav4803.

Links:

Nanotechnology (NIH)

What are genome editing and CRISPR-Cas9? (National Library of Medicine/NIH)

Sangeeta Bhatia (Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA)

Simone Schürle-Finke (ETH Zurich, Switzerland)

NIH Support: National Cancer Institute; National Institute of General Medical Sciences

Electricity-Conducting Bacteria May Inspire Next-Gen Medical Devices

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Technological advances with potential for improving human health sometimes come from the most unexpected places. An intriguing example is an electricity-conducting biological nanowire that holds promise for powering miniaturized pacemakers and other implantable electronic devices.

The nanowires come from a bacterium called Geobacter sulfurreducens, shown in the electron micrograph above. This rod-shaped microbe (white) was discovered two decades ago in soil collected from an unlikely place: a ditch outside of Norman, Oklahoma. The bug can conduct electricity along its arm-like appendages, and, in the hydrocarbon-contaminated, oxygen-depleted soil in which it lives, such electrical inputs and outputs are essentially the equivalent of breathing.

Scientists fascinated with G. sulfurreducens thought that its electricity had to be flowing through well-studied microbial appendages called pili. But, as the atomic structure of these nanowires (multi-colors, foreground) now reveals, these nanowires aren’t pili at all! Instead, the bacteria have manufactured unique submicroscopic arm-like structures. These arms consist of long, repetitive chains of a unique protein, each surrounding a core of iron-containing molecules.

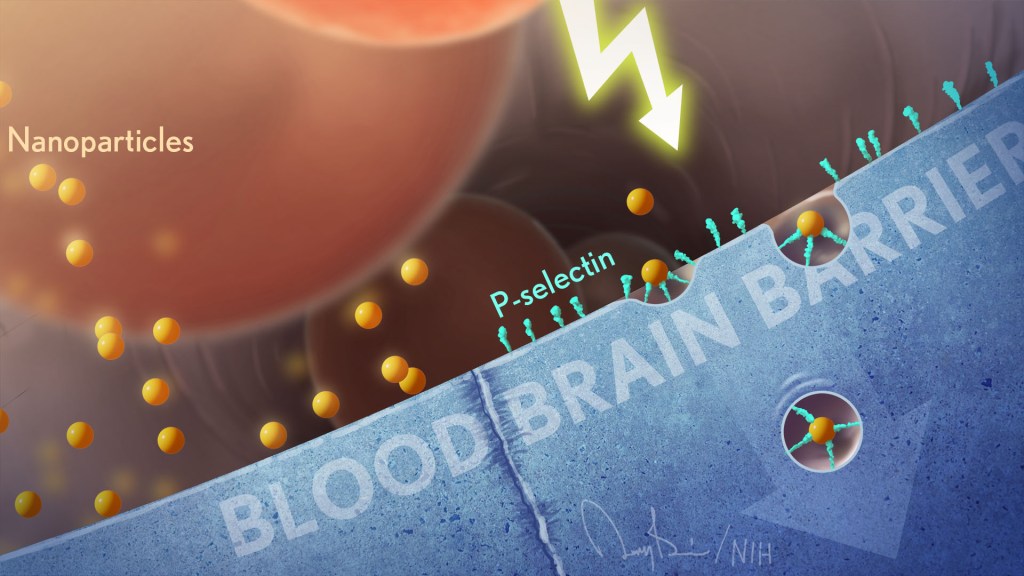

The surprising discovery, published in the journal Cell, was made by an NIH-funded team involving Edward Egelman, University of Virginia Health System, Charlottesville. Egelman’s lab has had a long interest in what’s called a type 4 pili. These strong, adhering appendages help certain infectious bacteria enter tissues and make people sick. In fact, they enable bugs like Neisseria meningitidis to cross the blood-brain barrier and cause potentially deadly bacterial meningitis. While other researchers had proposed that those same type 4 pili allowed G. sulfurreducens to conduct electricity, Egelman wasn’t so sure.

So, he took advantage of recent advances in cryo-electron microscopy, which involves flash-freezing molecules at extremely low temperatures before bombarding them with electrons to capture their images with a special camera. The cryo-EM images allowed his team to nail down the atomic structure of the nanowires, now called OmcS filaments.

Using those images and sophisticated bioinformatics, Egelman and team determined that OmcS proteins uniquely fit into the nanowires’ long repetitive chains, spacing their iron-bearing cores at regular intervals to transfer electrons and convey electricity. In fact, bacteria unable to produce OmcS proteins make filaments that conduct electricity 100 times less efficiently.

With these cryo-EM structures in hand, Egelman says his team will continue to explore their conductive properties. Such knowledge might someday be used to build biologically-inspired nanowires, measuring 1/100,000th the width of a human hair, to connect miniature electronic devices directly to living tissues. This is one more example of how nature’s ability to invent is pretty breathtaking—surely one wouldn’t have predicted the discovery of nanowires in a bacterium that lives in contaminated ditches.

Reference:

[1] Structure of Microbial Nanowires Reveals Stacked Hemes that Transport Electrons over Micrometers. Wang F, Gu Y, O’Brien JP, Yi SM, Yalcin SE, Srikanth V, Shen C, Vu D, Ing NL, Hochbaum AI, Egelman EH, Malvankar NS. Cell. 2019 Apr 4;177(2):361-369.

Links:

Electroactive microorganisms in bioelectrochemical systems. Logan BE, Rossi R, Ragab A, Saikaly PE. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2019 May;17(5):307-319.

High Resolution Electron Microscopy (National Cancer Institute/NIH)

Egelman Lab (University of Virginia, Charlottesville)

NIH Support: National Institute of General Medical Sciences; National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases; Common Fund

An Indisposable Idea from a Disposable Diaper

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Using a screwdriver on the tiny microcircuits arrayed inside a computer hard drive can be a real eye strain. Even more challenging is building the microcircuits or other electronic components at the nanoscale, one-billionth of a meter or less.

That’s why researchers are always on the lookout for new tools to help them work on such a minute scale. But some of these incredibly tiny tools and scaffolds can derive from very unexpected sources.

As published in the journal Science, an NIH-funded team has developed a technique called implosion fabrication to build impressively small and intricate components on the nanoscale [1]. Its secret ingredient: water-swollen gels that you’d find in a baby’s disposable diaper.

A baby’s disposable diaper? If that sounds familiar, my blog highlighted a related technique called expansion microscopy a few years ago that uses water-swollen gels that are generated from a compound used in diapers called sodium polyacrylate.

The previously-reported microscopy technique, from the lab of Edward Boyden, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, embeds biological samples in a fine web of sodium polyacrylate. When water is added, the gel expands, blowing up the specimen to 100 times its original size. This groundbreaking technique, called expansion microscopy, has enabled labs around the world to use conventional microscopes for high-resolution, nanoscale imaging.

In the latest work, Boyden’s team, including co-first authors Daniel Oran and Samuel Rodriques, asked a simple question: What would happen if they applied the sample preparation technique used for expansion microscopy—only in reverse?

To find out, Boyden’s team created millimeter-sized blocks of the super-absorbent sodium polyacrylate diaper compound. After using a nifty trick for attaching molecular anchors in a 3D pattern, they dehydrated the gel and voila! The structures imploded and shrank down to one-thousandth their original size, while holding their 3D shape.

During the process, they can add to the anchors a range of functional molecules or elements. These include DNA, nanoparticles, semiconductors, or almost anything that’s needed.

While more work is needed to perfect the new technique, the researchers have already shown it can create objects one cubic millimeter in size, engineered to include intricate details down to about 50 nanometers. For comparison, a virus is about 30 to 50 nanometers.

These latest findings come as a reminder that advances in biomedicine often lead in wonderful and unexpected new directions. Out of the NIH-funded efforts related to The Brain Research through Advancing Innovative Neurotechnologies® (BRAIN) Initiative, members of the Boyden Lab wanted to see the brain better using basic microscopes. Now, we have a widely-applicable promising new approach to nanofabrication.

Reference:

[1] 3D nanofabrication by volumetric deposition and controlled shrinkage of patterned scaffolds. Oran D, Rodriques SG, Gao R, Asano S, Skylar-Scott MA, Chen F, Tillberg PW, Marblestone AH, Boyden ES. Science. 2018 Dec 14;362(6420):1281-1285.

Links:

Size of the Nanoscale (Nano.gov)

Synthetic Neurobiology Group, Ed Boyden (MIT, Cambridge, MA)

The Brain Research through Advancing Innovative Neurotechnologies® (BRAIN) Initiative (NIH)

NIH Support: Common Fund; National Institute of Mental Health; National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering; National Human Genome Research Institute; National Institute on Drug Abuse; National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke

World’s Smallest Tic-Tac-Toe Game Built from DNA

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Check out the world’s smallest board game, a nanoscale match of tic-tac-toe being played out in a test tube with X’s and O’s made of DNA. But the innovative approach you see demonstrated in this video is much more than fun and games. Ultimately, researchers hope to use this technology to build tiny DNA machines for a wide variety of biomedical applications.

Here’s how it works. By combining two relatively recent technologies, an NIH-funded team led by Lulu Qian, California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, CA, created a “swapping mechanism” that programs dynamic interactions between complex DNA nanostructures [1]. The approach takes advantage of DNA’s modular structure, along with its tendency to self-assemble, based on the ability of the four letters of DNA’s chemical alphabet to pair up in an orderly fashion, A to T and C to G.

To make each of the X or O tiles in this game (displayed here in an animated cartoon version), researchers started with a single, long strand of DNA and many much shorter strands, called staples. When the sequence of DNA letters in each of those components is arranged just right, the longer strand will fold up into the desired 2D or 3D shape. This technique is called DNA origami because of its similarity to the ancient art of Japanese paper folding.

In the early days of DNA origami, researchers showed the technique could be used to produce miniature 2D images, such as a smiley face [2]. Last year, the Caltech group got more sophisticated—using DNA origami to produce the world’s smallest reproduction of the Mona Lisa [3].

In the latest work, published in Nature Communications, Qian, Philip Petersen and Grigory Tikhomirov first mixed up a solution of nine blank DNA origami tiles in a test tube. Those DNA tiles assembled themselves into a tic-tac-toe grid. Next, two players took turns adding one of nine X or O DNA tiles into the solution. Each of the game pieces was programmed precisely to swap out only one of the tile positions on the original, blank grid, based on the DNA sequences positioned along its edges.

When the first match was over, player X had won! More importantly for future biomedical applications, the original, blank grid had been fully reconfigured into a new structure, built of all-new, DNA-constructed components. That achievement shows not only can researchers use DNA to build miniature objects, they can also use DNA to repair or reconfigure such objects.

Of course, the ultimate aim of this research isn’t to build games or reproduce famous works of art. Qian wants to see her DNA techniques used to produce tiny automated machines, capable of performing basic tasks on a molecular scale. In fact, her team already has used a similar approach to build nano-sized DNA robots, programmed to sort molecules in much the same way that a person might sort laundry [4]. Such robots may prove useful in miniaturized approaches to drug discovery, development, manufacture, and/or delivery.

Another goal of the Caltech team is to demonstrate to the scientific community what’s possible with this leading-edge technology, in hopes that other researchers will pick up their innovative tools for their own applications. That would be a win-win for us all.

References:

[1] Information-based autonomous reconfiguration in systems of DNA nanostructures. Petersen P, Tikhomirov G, Qian L. Nat Commun. 2018 Dec 18;9(1):5362

[2] Folding DNA to create nanoscale shapes and patterns. Rothemund PW. Nature. 2006 Mar 16;440(7082):297-302.

[3] Fractal assembly of micrometre-scale DNA origami arrays with arbitrary patterns. Tikhomirov G, Petersen P, Qian L. Nature. 2017 Dec 6;552(7683):67-71.

[4] A cargo-sorting DNA robot. Thubagere AJ, Li W, Johnson RF, Chen Z, Doroudi S, Lee YL, Izatt G, Wittman S, Srinivas N, Woods D, Winfree E, Qian L. Science. 2017 Sep 15;357(6356).

Links:

Paul Rothemund—DNA Origami: Folded DNA as a Building Material for Molecular Devices (Cal Tech, Pasadena)

The World’s Smallest Mona Lisa (Caltech)

Qian Lab (Caltech, Pasadena, CA)

NIH Support: National Institute of General Medical Sciences

Detecting Cancer with a Herringbone Nanochip

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Credit: Yong Zeng, University of Kansas, Lawrence and Kansas City

The herringbone motif is familiar as the classic, V-shaped patterned weave long popular in tweed jackets. But the nano-sized herringbone pattern seen here is much more than a fashion statement. It helps to solve a tricky design problem for a cancer-detecting “lab-on-a-chip” device.

A research team, led by Yong Zeng, University of Kansas, Lawrence, and Andrew Godwin at the University of Kansas Medical Center, Kansas City. previously developed a lab-on-a-chip that senses exosomes. They are tiny bubble-shaped structures that most mammalian cells secrete constantly into the bloodstream [1]. Once thought of primarily as trash bags used by cells to rid themselves of waste products, exosomes carry important molecular information (RNA, protein, and metabolites) used by cells to communicate and influence the behavior of other cells.

What’s also interesting, tumor cells produce more exosomes than healthy cells. That makes these 30-to-150-nanometer structures (a nanometer is a billionth of a meter) potentially useful for detecting cancer. In fact, these NIH-funded researchers found that their microfluidic device can detect exosomes from ovarian cancer within a 2-microliter blood sample. That’s just 1/25th of a drop!

But there was a technical challenge. When such tiny samples are placed into microfluidic channels, the fluid and any particles within it tend to flow in parallel layers without any mixing between them. As a result, exosomes can easily pass through undetected, without ever touching the biosensors on the surface of the chip.

That’s where the herringbone comes in. As reported in Nature Biomedical Engineering, when fluid flows over those 3D herringbone structures, it produces a whirlpool-like effect [2]. As a result, exosomes are more reliably swept into contact with the biosensors.

The team’s distinctive herringbone structures also increase the surface area within the chip. Because the surface is also porous, it allows fluid to drain out slowly to further encourage exosomes to reach the biosensors.

Zeng’s team put their “lab-on-a-chip” to the test using blood samples from 20 patients with ovarian cancer and 10 age-matched controls. The chip was able to detect rapidly the presence of exosomal proteins known to be associated with ovarian cancer.

The researchers report that their device is sensitive enough to detect just 10 exosomes in a 1-microliter sample. It also could be easily adapted to detect exosomal proteins associated with other cancers, and perhaps other conditions as well.

Zeng and colleagues haven’t mentioned whether they’re also looking into trying other geometric patterns in their designs. But the next time you see a tweed jacket, just remember that there’s more to its herringbone pattern than meets the eye.

References:

[1] Ultrasensitive microfluidic analysis of circulating exosomes using a nanostructured graphene oxide/polydopamine coating. Zhang P, He M, Zeng Y. Lab Chip. 2016 Aug 2;16(16):3033-3042.

[2] Ultrasensitive detection of circulating exosomes with a 3D-nanopatterned microfluidic chip. Zhang P, Zhou X, He M, Shang Y, Tetlow AL, Godwin AK, Zeng Y. Nature Biomedical Engineering. February 25, 2019.

Links:

Ovarian, Fallopian Tube, and Primary Peritoneal Cancer—Patient Version (National Cancer Institute/NIH)

Cancer Screening Overview—Patient Version (NCI/NIH)

Extracellular RNA Communication (Common Fund/NIH)

Zeng Lab (University of Kansas, Lawrence)

Godwin Laboratory (University of Kansas Medical Center, Kansas City)

NIH Support: National Cancer Institute

‘Nanoantennae’ Make Infrared Vision Possible

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Credit: Ma et al. Cell, 2019

Infrared vision often brings to mind night-vision goggles that allow soldiers to see in the dark, like you might have seen in the movie Zero Dark Thirty. But those bulky goggles may not be needed one day to scope out enemy territory or just the usual things that go bump in the night. In a dramatic advance that brings together material science and the mammalian vision system, researchers have just shown that specialized lab-made nanoparticles applied to the retina, the thin tissue lining the back of the eye, can extend natural vision to see in infrared light.

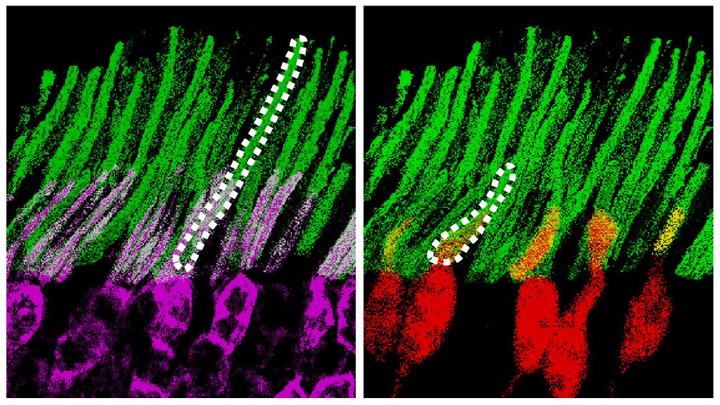

The researchers showed in mouse studies that their specially crafted nanoparticles bind to the retina’s light-sensing cells, where they act like “nanoantennae” for the animals to see and recognize shapes in infrared—day or night—for at least 10 weeks. Even better, the mice maintained their normal vision the whole time and showed no adverse health effects. In fact, some of the mice are still alive and well in the lab, although their ability to see in infrared may have worn off.

When light enters the eyes of mice, humans, or any mammal, light-sensing cells in the retina absorb wavelengths within the range of visible light. (That’s roughly from 400 to 700 nanometers.) While visible light includes all the colors of the rainbow, it actually accounts for only a fraction of the full electromagnetic spectrum. Left out are the longer wavelengths of infrared light. That makes infrared light invisible to the naked eye.

In the study reported in the journal Cell, an international research team including Gang Han, University of Massachusetts Medical School, Worcester, wanted to find a way for mammalian light-sensing cells to absorb and respond to the longer wavelengths of infrared [1]. It turns out Han’s team had just the thing to do it.

His NIH-funded team was already working on the nanoparticles now under study for application in a field called optogenetics—the use of light to control living brain cells [2]. Optogenetics normally involves the stimulation of genetically modified brain cells with blue light. The trouble is that blue light doesn’t penetrate brain tissue well.

That’s where Han’s so-called upconversion nanoparticles (UCNPs) came in. They attempt to get around the normal limitations of optogenetic tools by incorporating certain rare earth metals. Those metals have a natural ability to absorb lower energy infrared light and convert it into higher energy visible light (hence the term upconversion).

But could those UCNPs also serve as miniature antennae in the eye, receiving infrared light and emitting readily detected visible light? To find out in mouse studies, the researchers injected a dilute solution containing UCNPs into the back of eye. Such sub-retinal injections are used routinely by ophthalmologists to treat people with various eye problems.

These UCNPs were modified with a protein that allowed them to stick to light-sensing cells. Because of the way that UCNPs absorb and emit wavelengths of light energy, they should to stick to the light-sensing cells and make otherwise invisible infrared light visible as green light.

Their hunch proved correct, as mice treated with the UCNP solution began seeing in infrared! How could the researchers tell? First, they shined infrared light into the eyes of the mice. Their pupils constricted in response just as they would with visible light. Then the treated mice aced a series of maneuvers in the dark that their untreated counterparts couldn’t manage. The treated animals also could rely on infrared signals to make out shapes.

The research is not only fascinating, but its findings may also have a wide range of intriguing applications. One could imagine taking advantage of the technology for use in hiding encrypted messages in infrared or enabling people to acquire a temporary, built-in ability to see in complete darkness.

With some tweaks and continued research to confirm the safety of these nanoparticles, the system might also find use in medicine. For instance, the nanoparticles could potentially improve vision in those who can’t see certain colors. While such infrared vision technologies will take time to become more widely available, it’s a great example of how one area of science can cross-fertilize another.

References:

[1] Mammalian Near-Infrared Image Vision through Injectable and Self-Powered Retinal Nanoantennae. Ma Y, Bao J, Zhang Y, Li Z, Zhou X, Wan C, Huang L, Zhao Y, Han G, Xue T. Cell. 2019 Feb 27. [Epub ahead of print]

[2] Near-Infrared-Light Activatable Nanoparticles for Deep-Tissue-Penetrating Wireless Optogenetics. Yu N, Huang L, Zhou Y, Xue T, Chen Z, Han G. Adv Healthc Mater. 2019 Jan 11:e1801132.

Links:

Diagram of the Eye (National Eye Institute/NIH)

Infrared Waves (NASA)

Visible Light (NASA)

Han Lab (University of Massachusetts, Worcester)

NIH Support: National Institute of Mental Health; National Institute of General Medical Sciences

Skin Cells Can Be Reprogrammed In Vivo

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Thousands of Americans are rushed to the hospital each day with traumatic injuries. Daniel Gallego-Perez hopes that small chips similar to the one that he’s touching with a metal stylus in this photo will one day be a part of their recovery process.

The chip, about one square centimeter in size, includes an array of tiny channels with the potential to regenerate damaged tissue in people. Gallego-Perez, a researcher at The Ohio State University Colleges of Medicine and Engineering, Columbus, has received a 2018 NIH Director’s New Innovator Award to develop the chip to reprogram skin and other cells to become other types of tissue needed for healing. The reprogrammed cells then could regenerate and restore injured neural or vascular tissue right where it’s needed.

Gallego-Perez and his Ohio State colleagues wondered if it was possible to engineer a device placed on the skin that’s capable of delivering reprogramming factors directly into cells, eliminating the need for the viral delivery vectors now used in such work. While such a goal might sound futuristic, Gallego-Perez and colleagues offered proof-of-principle last year in Nature Nanotechnology that such a chip can reprogram skin cells in mice. [1]

Here’s how it works: First, the chip’s channels are loaded with specific reprogramming factors, including DNA or proteins, and then the chip is placed on the skin. A small electrical current zaps the chip’s channels, driving reprogramming factors through cell membranes and into cells. The process, called tissue nanotransfection (TNT), is finished in milliseconds.

To see if the chips could help heal injuries, researchers used them to reprogram skin cells into vascular cells in mice. Not only did the technology regenerate blood vessels and restore blood flow to injured legs, the animals regained use of those limbs within two weeks of treatment.

The researchers then went on to show that they could use the chips to reprogram mouse skin cells into neural tissue. When proteins secreted by those reprogrammed skin cells were injected into mice with brain injuries, it helped them recover.

In the newly funded work, Gallego-Perez wants to take the approach one step further. His team will use the chip to reprogram harder-to-reach tissues within the body, including peripheral nerves and the brain. The hope is that the device will reprogram cells surrounding an injury, even including scar tissue, and “repurpose” them to encourage nerve repair and regeneration. Such an approach may help people who’ve suffered a stroke or traumatic nerve injury.

If all goes well, this TNT method could one day fill an important niche in emergency medicine. Gallego-Perez’s work is also a fine example of just one of the many amazing ideas now being pursued in the emerging field of regenerative medicine.

Reference:

[1] Topical tissue nano-transfection mediates non-viral stroma reprogramming and rescue. Gallego-Perez D, Pal D, Ghatak S, Malkoc V, Higuita-Castro N, Gnyawali S, Chang L, Liao WC, Shi J, Sinha M, Singh K, Steen E, Sunyecz A, Stewart R, Moore J, Ziebro T, Northcutt RG, Homsy M, Bertani P, Lu W, Roy S, Khanna S, Rink C, Sundaresan VB, Otero JJ, Lee LJ, Sen CK. Nat Nanotechnol. 2017 Oct;12(10):974-979.

Links:

Stroke Information (National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke/NIH)

Burns and Traumatic Injury (NIH)

Peripheral Neuropathy (National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke/NIH)

Video: Breakthrough Device Heals Organs with a Single Touch (YouTube)

Gallego-Perez Lab (The Ohio State University College of Medicine, Columbus)

Gallego-Perez Project Information (NIH RePORTER)

NIH Support: Common Fund; National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke

Next Page