cryo-EM

3D Animation Captures Viral Infection in Action

Posted on by Lawrence Tabak, D.D.S., Ph.D.

With the summer holiday season now in full swing, the blog will also swing into its annual August series. For most of the month, I will share with you just a small sampling of the colorful videos and snapshots of life captured in a select few of the hundreds of NIH-supported research labs around the country.

To get us started, let’s turn to the study of viruses. Researchers now can generate vast amounts of data relatively quickly on a virus of interest. But data are often displayed as numbers or two-dimensional digital images on a computer screen. For most virologists, it’s extremely helpful to see a virus and its data streaming in three dimensions. To do so, they turn to a technological tool that we all know so well: animation.

This research animation features the chikungunya virus, a sometimes debilitating, mosquito-borne pathogen transmitted mainly in developing countries in Africa, Asia and the Americas. The animation illustrates large amounts of research data to show how the chikungunya virus infects our cells and uses its specialized machinery to release its genetic material into the cell and seed future infections. Let’s take a look.

In the opening seconds, you see how receptor binding glycoproteins (light blue), which are proteins with a carbohydrate attached on the viral surface, dock with protein receptors (yellow) on a host cell. At five seconds, the virus is drawn inside the cell. The change in the color of the chikungunya particle shows that it’s coated in a vesicle, which helps the virus make its way unhindered through the cytoplasm.

At 10 seconds, the virus then enters an endosome, ubiquitous bubble-like compartments that transport material from outside the cell into the cytosol, the fluid part of the cytoplasm. Once inside the endosome, the acidic environment makes other glycoproteins (red, blue, yellow) on the viral surface change shape and become more flexible and dynamic. These glycoproteins serve as machinery that enables them to reach out and grab onto the surrounding endosome membrane, which ultimately will be fused with the virus’s own membrane.

As more of those fusion glycoproteins grab on, fold back on themselves, and form into hairpin-like shapes, they pull the membranes together. The animation illustrates not only the changes in protein organization, but the resulting effects on the integrity of the membrane structures as this dynamic process proceeds. At 53 seconds, the viral protein shell, or capsid (green), which contains the virus’ genetic instructions, is released back out into the cell where it will ultimately go on to make more virus.

This remarkable animation comes from Margot Riggi and Janet Iwasa, experts in visualizing biology at the University of Utah’s Animation Lab, Salt Lake City. Their data source was researcher Kelly Lee, University of Washington, Seattle, who collaborated closely with Riggi and Iwasa on this project. The final product was considered so outstanding that it took the top prize for short videos in the 2022 BioArt Awards competition, sponsored by the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology (FASEB).

The Lee lab uses various research methods to understand the specific shape-shifting changes that chikungunya and other viruses perform as they invade and infect cells. One of the lab’s key visual tools is cryo-electron microscopy (Cryo-EM), specifically cryo-electron tomography (cryo-ET). Cryto-ET enables complex 3D structures, including the intermediate state of biological reactions, to be captured and imaged in remarkably fine detail.

In a study in the journal Nature Communications [1] last year, Lee’s team used cryo-ET to reveal how the chikungunya virus invades and delivers its genetic cargo into human cells to initiate a new infection. While Lee’s cryo-ET data revealed stages of the virus entry process and fine structural details of changes to the virus as it enters a cell and starts an infection, it still represented a series of snapshots with missing steps in between. So, Lee’s lab teamed up with The Animation Lab to help beautifully fill in the gaps.

Visualizing chikungunya and similar viruses in action not only makes for informative animations, it helps researchers discover better potential targets to intervene in this process. This basic research continues to make progress, and so do ongoing efforts to develop a chikungunya vaccine [2] and specific treatments that would help give millions of people relief from the aches, pains, and rashes associated with this still-untreatable infection.

References:

[1] Visualization of conformational changes and membrane remodeling leading to genome delivery by viral class-II fusion machinery. Mangala Prasad V, Blijleven JS, Smit JM, Lee KK. Nat Commun. 2022 Aug 15;13(1):4772. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-32431-9. PMID: 35970990; PMCID: PMC9378758.

[2] Experimental chikungunya vaccine is safe and well-tolerated in early trial, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases news release, April 27, 2020.

Links:

Chikungunya Virus (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta)

Global Arbovirus Initiative (World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland)

The Animation Lab (University of Utah, Salt Lake City)

Video: Janet Iwasa (TED Speaker)

Lee Lab (University of Washington, Seattle)

BioArt Awards (Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology, Rockville, MD)

NIH Support: National Institute of General Medical Sciences; National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases

Cryo-EM Scores Again

Posted on by Lawrence Tabak, D.D.S., Ph.D.

Human neurons are long, spindly structures, but if you could zoom in on their surfaces at super-high resolution, you’d see surprisingly large pores. They act as gated channels that open and close for ions and other essential molecules of life to pass in and out the cell. This rapid exchange of ions and other molecules is how neurons communicate, and why we humans can sense, think, move, and respond to the world around us [1].

Because these gated channels are so essential to neurons, mapping their precise physical structures at high-resolution has profound implications for informing future studies on the brain and nervous system. Good for us in these high-tech times that structural biologists keep getting better at imaging these 3D pores.

In fact, as just published in the journal Nature Communications [2], a team of NIH-supported scientists imaged the molecular structure of a gated pore of major research interest. The pore is called calcium homeostasis modulator 1 (CALHM1). Pictured below, you can view its 3D structure at near atomic resolution [2]. Keep in mind, this relatively large neuronal pore still measures approximately 50,000 times smaller than the width of a hair.

The structure comes from a research team led by Hiro Furukawa, Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, NY. He and his team relied on cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) to produce the first highly precise 3D models of CALHM1.

Cryo-EM involves flash-freezing molecules in liquid ethane and bombarding them with electrons to capture their images with a special camera. When all goes well, cryo-EM can reveal the structure of intricate macromolecular complexes in a matter of weeks.

Furukawa’s team had earlier studied CALHM1 from chickens with cryo-EM [3], and their latest work reveals that the human version is quite similar. Eight copies of the CALHM1 protein assemble to form the circular channel. Each of the protein subunits has a flexible arm that allows it to reach into the central opening, which the researchers now suspect allows the channels to open and close in a highly controlled manner. The researchers have likened the channels’ eight flexible arms to the arms of an octopus.

The researchers also found that fatty molecules called phospholipids play a critical role in stabilizing and regulating the eight-part channel. They used simulations to demonstrate how pockets in the CALHM1 channel binds this phospholipid over cholesterol to shore up the structure and function properly. Interestingly, these phospholipid molecules are abundant in many healthy foods, such as eggs, lean meats, and seafood.

Researchers knew that an inorganic chemical called ruthenium red can block the function of the CALHM1 channel. They’ve now shown precisely how this works. The structural details indicate that ruthenium red physically lodges in and plugs up the channel.

These details also may be useful in future efforts to develop drugs designed to target and modify the function of these channels in helpful ways. For instance, on our tongues, the channel plays a role in our ability to perceive sweet, sour, or umami (savory) flavors. In our brains, studies show the abnormal function of CALHM1 may be implicated in the plaques that accumulate in the brains of people with Alzheimer’s disease.

There are far too many other normal and abnormal functions to mention here in this brief post. Suffice it to say, I’ll look forward to seeing what this enabling research yields in the years ahead.

References:

[1] On the molecular nature of large-pore channels. Syrjanen, J., Michalski, K., Kawate, T., and Furukawa, H. J Mol Biol. 2021 Aug 20;433(17):166994. DOI: 10.1016/j.jmb.2021.166994. Epub 2021 Apr 16. PMID: 33865869; PMCID: PMC8409005.

[2] Structure of human CALHM1 reveals key locations for channel regulation and blockade by ruthenium red. Syrjänen JL, Epstein M, Gómez R, Furukawa H. Nat Commun. 2023 Jun 28;14(1):3821. DOI: 10.1038/s41467-023-39388-3. PMID: 37380652; PMCID: PMC10307800.

[3] Structure and assembly of calcium homeostasis modulator proteins. Syrjanen JL, Michalski K, Chou TH, Grant T, Rao S, Simorowski N, Tucker SJ, Grigorieff N, Furukawa H. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2020 Feb;27(2):150-159. DOI: 10.1038/s41594-019-0369-9. Epub 2020 Jan 27. PMID: 31988524; PMCID: PMC7015811.

Links:

Brain Basics: The Life and Death of a Neuron (National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke/NIH)

Alzheimer’s Disease (National Institute on Aging/NIH)

Furukawa Lab (Cold Spring Harbor Lab, Cold Spring Harbor, NY)

NIH Support: National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke; National Institute of Mental Health

What A Year It Was for Science Advances!

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

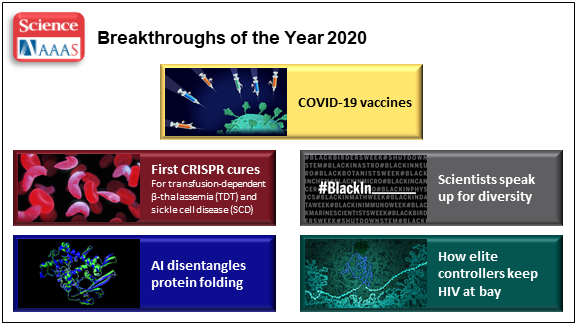

At the close of every year, editors and writers at the journal Science review the progress that’s been made in all fields of science—from anthropology to zoology—to select the biggest advance of the past 12 months. In most cases, this Breakthrough of the Year is as tough to predict as the Oscar for Best Picture. Not in 2020. In a year filled with a multitude of challenges posed by the emergence of the deadly coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-2019), the breakthrough was the development of the first vaccines to protect against this pandemic that’s already claimed the lives of more than 360,000 Americans.

In keeping with its annual tradition, Science also selected nine runner-up breakthroughs. This impressive list includes at least three areas that involved efforts supported by NIH: therapeutic applications of gene editing, basic research understanding HIV, and scientists speaking up for diversity. Here’s a quick rundown of all the pioneering advances in biomedical research, both NIH and non-NIH funded:

Shots of Hope. A lot of things happened in 2020 that were unprecedented. At the top of the list was the rapid development of COVID-19 vaccines. Public and private researchers accomplished in 10 months what normally takes about 8 years to produce two vaccines for public use, with more on the way in 2021. In my more than 25 years at NIH, I’ve never encountered such a willingness among researchers to set aside their other concerns and gather around the same table to get the job done fast, safely, and efficiently for the world.

It’s also pretty amazing that the first two conditionally approved vaccines from Pfizer and Moderna were found to be more than 90 percent effective at protecting people from infection with SARS-CoV-2, the coronavirus that causes COVID-19. Both are innovative messenger RNA (mRNA) vaccines, a new approach to vaccination.

For this type of vaccine, the centerpiece is a small, non-infectious snippet of mRNA that encodes the instructions to make the spike protein that crowns the outer surface of SARS-CoV-2. When the mRNA is injected into a shoulder muscle, cells there will follow the encoded instructions and temporarily make copies of this signature viral protein. As the immune system detects these copies, it spurs the production of antibodies and helps the body remember how to fend off SARS-CoV-2 should the real thing be encountered.

It also can’t be understated that both mRNA vaccines—one developed by Pfizer and the other by Moderna in conjunction with NIH’s National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases—were rigorously evaluated in clinical trials. Detailed data were posted online and discussed in all-day meetings of an FDA Advisory Committee, open to the public. In fact, given the high stakes, the level of review probably was more scientifically rigorous than ever.

First CRISPR Cures: One of the most promising areas of research now underway involves gene editing. These tools, still relatively new, hold the potential to fix gene misspellings—and potentially cure—a wide range of genetic diseases that were once to be out of reach. Much of the research focus has centered on CRISPR/Cas9. This highly precise gene-editing system relies on guide RNA molecules to direct a scissor-like Cas9 enzyme to just the right spot in the genome to cut out or correct a disease-causing misspelling.

In late 2020, a team of researchers in the United States and Europe succeeded for the first time in using CRISPR to treat 10 people with sickle cell disease and transfusion-dependent beta thalassemia. As published in the New England Journal of Medicine, several months after this non-heritable treatment, all patients no longer needed frequent blood transfusions and are living pain free [1].

The researchers tested a one-time treatment in which they removed bone marrow from each patient, modified the blood-forming hematopoietic stem cells outside the body using CRISPR, and then reinfused them into the body. To prepare for receiving the corrected cells, patients were given toxic bone marrow ablation therapy, in order to make room for the corrected cells. The result: the modified stem cells were reprogrammed to switch back to making ample amounts of a healthy form of hemoglobin that their bodies produced in the womb. While the treatment is still risky, complex, and prohibitively expensive, this work is an impressive start for more breakthroughs to come using gene editing technologies. NIH, including its Somatic Cell Genome Editing program, continues to push the technology to accelerate progress and make gene editing cures for many disorders simpler and less toxic.

Scientists Speak Up for Diversity: The year 2020 will be remembered not only for COVID-19, but also for the very public and inescapable evidence of the persistence of racial discrimination in the United States. Triggered by the killing of George Floyd and other similar events, Americans were forced to come to grips with the fact that our society does not provide equal opportunity and justice for all. And that applies to the scientific community as well.

Science thrives in safe, diverse, and inclusive research environments. It suffers when racism and bigotry find a home to stifle diversity—and community for all—in the sciences. For the nation’s leading science institutions, there is a place and a calling to encourage diversity in the scientific workplace and provide the resources to let it flourish to everyone’s benefit.

For those of us at NIH, last year’s peaceful protests and hashtags were noticed and taken to heart. That’s one of the many reasons why we will continue to strengthen our commitment to building a culturally diverse, inclusive workplace. For example, we have established the NIH Equity Committee. It allows for the systematic tracking and evaluation of diversity and inclusion metrics for the intramural research program for each NIH institute and center. There is also the recently founded Distinguished Scholars Program, which aims to increase the diversity of tenure track investigators at NIH. Recently, NIH also announced that it will provide support to institutions to recruit diverse groups or “cohorts” of early-stage research faculty and prepare them to thrive as NIH-funded researchers.

AI Disentangles Protein Folding: Proteins, which are the workhorses of the cell, are made up of long, interconnected strings of amino acids that fold into a wide variety of 3D shapes. Understanding the precise shape of a protein facilitates efforts to figure out its function, its potential role in a disease, and even how to target it with therapies. To gain such understanding, researchers often try to predict a protein’s precise 3D chemical structure using basic principles of physics—including quantum mechanics. But while nature does this in real time zillions of times a day, computational approaches have not been able to do this—until now.

Of the roughly 170,000 proteins mapped so far, most have had their structures deciphered using powerful imaging techniques such as x-ray crystallography and cryo–electron microscopy (cryo-EM). But researchers estimate that there are at least 200 million proteins in nature, and, as amazing as these imaging techniques are, they are laborious, and it can take many months or years to solve 3D structure of a single protein. So, a breakthrough certainly was needed!

In 2020, researchers with the company Deep Mind, London, developed an artificial intelligence (AI) program that rapidly predicts most protein structures as accurately as x-ray crystallography and cryo-EM can map them [2]. The AI program, called AlphaFold, predicts a protein’s structure by computationally modeling the amino acid interactions that govern its 3D shape.

Getting there wasn’t easy. While a complete de novo calculation of protein structure still seemed out of reach, investigators reasoned that they could kick start the modeling if known structures were provided as a training set to the AI program. Utilizing a computer network built around 128 machine learning processors, the AlphaFold system was created by first focusing on the 170,000 proteins with known structures in a reiterative process called deep learning. The process, which is inspired by the way neural networks in the human brain process information, enables computers to look for patterns in large collections of data. In this case, AlphaFold learned to predict the underlying physical structure of a protein within a matter of days. This breakthrough has the potential to accelerate the fields of structural biology and protein research, fueling progress throughout the sciences.

How Elite Controllers Keep HIV at Bay: The term “elite controller” might make some people think of video game whizzes. But here, it refers to the less than 1 percent of people living with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) who’ve somehow stayed healthy for years without taking antiretroviral drugs. In 2020, a team of NIH-supported researchers figured out why this is so.

In a study of 64 elite controllers, published in the journal Nature, the team discovered a link between their good health and where the virus has inserted itself in their genomes [3]. When a cell transcribes a gene where HIV has settled, this so-called “provirus,” can produce more virus to infect other cells. But if it settles in a part of a chromosome that rarely gets transcribed, sometimes called a gene desert, the provirus is stuck with no way to replicate. Although this discovery won’t cure HIV/AIDS, it points to a new direction for developing better treatment strategies.

In closing, 2020 presented more than its share of personal and social challenges. Among those challenges was a flood of misinformation about COVID-19 that confused and divided many communities and even families. That’s why the editors and writers at Science singled out “a second pandemic of misinformation” as its Breakdown of the Year. This divisiveness should concern all of us greatly, as COVID-19 cases continue to soar around the country and our healthcare gets stretched to the breaking point. I hope and pray that we will all find a way to come together, both in science and in society, as we move forward in 2021.

References:

[1] CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing for sickle cell disease and β-thalassemia. Frangoul H et al. N Engl J Med. 2020 Dec 5.

[2] ‘The game has changed.’ AI triumphs at protein folding. Service RF. Science. 04 Dec 2020.

[3] Distinct viral reservoirs in individuals with spontaneous control of HIV-1. Jiang C et al. Nature. 2020 Sep;585(7824):261-267.

Links:

COVID-19 Research (NIH)

2020 Science Breakthrough of the Year (American Association for the Advancement of Science, Washington, D.C)

Caught on Camera: Neutralizing Antibodies Interacting with SARS-CoV-2

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

As this long year enters its final month, there is good reason to look ahead to 2021 with optimism that the COVID-19 pandemic will finally be contained. The Food and Drug Administration is now reviewing the clinical trial data of the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines to ensure their safety and efficacy. If all goes well, emergency use authorization could come very soon, allowing immunizations to begin.

Work also continues on developing better therapeutics against SARS-CoV-2, the novel coronavirus that causes COVID-19. Though we’ve learned a great deal about this coronavirus in a short time, structural biologists continue to produce more detailed images that reveal more precisely where and how to target SARS-CoV-2. This research often involves neutralizing antibodies that circulate in the blood of most people who’ve recovered from COVID-19. The study of such antibodies and how they interact with SARS-CoV-2 offers critical biological clues into how to treat and prevent COVID-19.

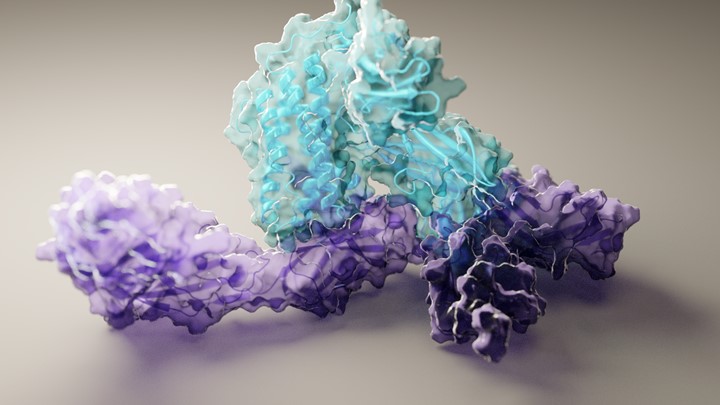

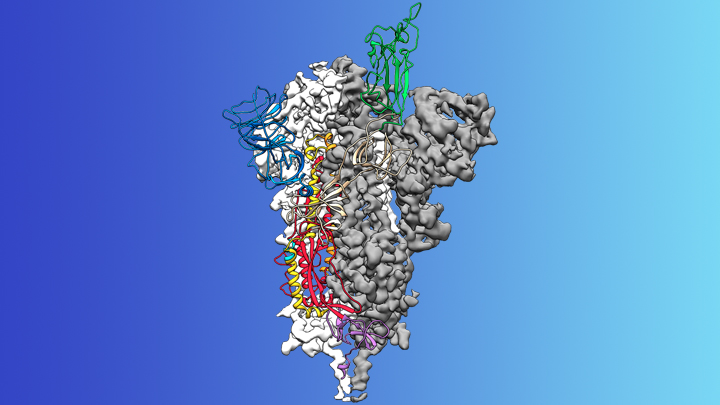

A recent study in the journal Nature brings more progress, providing the most in-depth analysis yet of how human neutralizing antibodies physically grip SARS-CoV-2 to block it from binding to our cells [1]. To conduct this analysis, a team of NIH-supported structural biologists, led by postdoc Christopher Barnes and Pamela Björkman, California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, used the power of cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) to capture complex molecular interactions at near-atomic scale.

People infected with SARS-CoV-2 (or any foreign substance, for that matter) generate thousands of different versions of attack antibodies. Some of these antibodies are very good at sticking to the coronavirus, while others attach only loosely. Barnes used cryo-EM to capture highly intricate pictures of eight different human neutralizing antibodies bound tightly to SARS-CoV-2. Each of these antibodies, which had been isolated from patients a few weeks after they developed symptoms of COVID-19, had been shown in lab tests to be highly effective at blocking infection.

The researchers mapped all physical interactions between several human neutralizing antibodies and SARS-CoV-2’s spike protein that stud its surface. The virus uses these spiky extensions to infect a human cell by grabbing on to the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptor. The molecular encounter between the coronavirus and ACE2 takes place via one or more of a trio of three protein domains, called receptor-binding domains (RBDs), that jut out from its spikes. RBDs flap up and down in the fluid surrounding cells, “reaching up” to touch and enter, or “laying down” to hide from an infected person’s antibodies and immune cells. Only an “up” RBD can attach to ACE2 and get into a cell.

Taken together with other structural information known about SARS-CoV-2, Barnes’ cryo-EM snapshots revealed four different types of shapes, or classes, of antibody-spike combinations. These high-resolution molecular views show that human neutralizing antibodies interact in many different ways with SARS-CoV-2: blocking access to either one or more RBDs in their “up” or “down” positions.

These results tell us a number of things, including underscoring why strategies that combine multiple types of antibodies in an “antibody cocktail” might likely offer broader protection against infection than using just a single type of antibody. Indeed, that approach is currently being tested in patients with COVID-19.

The findings also provide a molecular guide for custom-designing synthetic antibodies in the lab to foil SARS-CoV-2. As one example, Barnes and his team observed that one antibody completely locked all three RBDs into closed (“down”) positions. As you might imagine, scientists might want to copy that antibody type when designing an antibody-based drug or vaccine.

It is tragic that hundreds of thousands of people have died from this terrible new disease. Yet the immune system helps most to recover. Learning as much as we possibly can from those individuals who’ve been infected and returned to health should help us understand how to heal others who develop COVID-19, as well as inform precision design of additional vaccines that are molecularly targeted to this new foe.

While we look forward to the arrival of COVID-19 vaccines and their broad distribution in 2021, each of us needs to remember to practice the three W’s: Wear a mask. Watch your distance (stay 6 feet apart). Wash your hands often. In parallel with everyone adopting these critical public health measures, the scientific community is working harder than ever to meet this moment, doing everything possible to develop safe and effective ways of treating and preventing COVID-19.

Reference:

[1] SARS-CoV-2 neutralizing antibody structures inform therapeutic strategies. Barnes CO, Jette CA, Abernathy ME, et al. Nature. 2020 Oct 12. [Epub ahead of print].

Links:

Coronavirus (COVID-19) (NIH)

Combat COVID (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Washington, D.C.)

Freezing a Moment in Time: Snapshots of Cryo-EM Research (National Institute of General Medical Sciences/NIH)

Björkman Lab (California Institute of Technology, Pasadena)

NIH Support: National Institute of General Medical Sciences; National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases

Protein Mapping Study Reveals Valuable Clues for COVID-19 Drug Development

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

One way to fight COVID-19 is with drugs that directly target SARS-CoV-2, the novel coronavirus that causes the disease. That’s the strategy employed by remdesivir, the only antiviral drug currently authorized by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to treat COVID-19. Another promising strategy is drugs that target the proteins within human cells that the virus needs to infect, multiply, and spread.

With the aim of developing such protein-targeted antiviral drugs, a large, international team of researchers, funded in part by the NIH, has precisely and exhaustively mapped all of the interactions that take place between SARS-CoV-2 proteins and the human proteins found within infected host cells. They did the same for the related coronaviruses: SARS-CoV-1, the virus responsible for outbreaks of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS), which ended in 2004; and MERS-CoV, the virus that causes the now-rare Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS).

The goal, as reported in the journal Science, was to use these protein “interactomes” to uncover vulnerabilities shared by all three coronaviruses. The hope is that the newfound knowledge about these shared proteins—and the pathways to which they belong—will inform efforts to develop new kinds of broad-spectrum antiviral therapeutics for use in the current and future coronavirus outbreaks.

Facilitated by the Quantitative Biosciences Institute Research Group, the team, which included David E. Gordon and Nevan Krogan, University of California, San Francisco, and hundreds of other scientists from around the world, successfully mapped nearly 400 protein-protein interactions between SARS-CoV-2 and human proteins.

You can see one of these interactions in the video above. The video starts out with an image of the Orf9b protein of SARS-CoV-2, which normally consists of two linked molecules (blue and orange). But researchers discovered that Orf9b dissociates into a single molecule (orange) when it interacts with the human protein TOM70 (teal). Through detailed structural analysis using cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM), the team went on to predict that this interaction may disrupt a key interaction between TOM70 and another human protein called HSP90.

While further study is needed to understand all the details and their implications, it suggests that this interaction may alter important aspects of the human immune response, including blocking interferon signals that are crucial for sounding the alarm to prevent serious illness. While there is no drug immediately available to target Orf9b or TOM70, the findings point to this interaction as a potentially valuable target for treating COVID-19 and other diseases caused by coronaviruses.

This is just one intriguing example out of 389 interactions between SARS-CoV-2 and human proteins uncovered in the new study. The researchers also identified 366 interactions between human and SARS-CoV-1 proteins and 296 for MERS-CoV. They were especially interested in shared interactions that take place between certain human proteins and the corresponding proteins in all three coronaviruses.

To learn more about the significance of these protein-protein interactions, the researchers conducted a series of studies to find out how disrupting each of the human proteins influences SARS-CoV-2’s ability to infect human cells. These studies narrowed the list to 73 human proteins that the virus depends on to replicate.

Among them were the receptor for an inflammatory signaling molecule called IL-17, which has been suggested as an indicator of COVID-19 severity. Two other human proteins—PGES-2 and SIGMAR1—were of particular interest because they are targets of existing drugs, including the anti-inflammatory indomethacin for PGES-2 and antipsychotics like haloperidol for SIGMAR1.

To connect the molecular-level data to existing clinical information for people with COVID-19, the researchers looked to medical billing data for nearly 740,000 Americans treated for COVID-19. They then zeroed in on those individuals who also happened to have been treated with drugs targeting PGES-2 or SIGMAR1. And the results were quite striking.

They found that COVID-19 patients taking indomethacin were less likely than those taking an anti-inflammatory that doesn’t target PGES-2 to require treatment at a hospital. Similarly, COVID-19 patients taking antipsychotic drugs like haloperidol that target SIGMAR1 were half as likely as those taking other types of antipsychotic drugs to require mechanical ventilation.

More research is needed before we can think of testing these or similar drugs against COVID-19 in human clinical trials. Yet these findings provide a remarkable demonstration of how basic molecular and structural biological findings can be combined with clinical data to yield valuable new clues for treating COVID-19 and other viral illnesses, perhaps by repurposing existing drugs. Not only is NIH-supported basic science essential for addressing the challenges of the current pandemic, it is building a strong foundation of fundamental knowledge that will make us better prepared to deal with infectious disease threats in the future.

Reference:

[1] Comparative host-coronavirus protein interaction networks reveal pan-viral disease mechanisms. Gordon DE et al. Science. 2020 Oct 15:eabe9403.

Links:

Coronavirus (COVID-19) (NIH)

Krogan Lab (University of California, San Francisco)

NIH Support: National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases; National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke; National Institute of General Medical Sciences

Structural Biology Points Way to Coronavirus Vaccine

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Credit: McLellan Lab, University of Texas at Austin

The recent COVID-19 outbreak of a novel type of coronavirus that began in China has prompted a massive global effort to contain and slow its spread. Despite those efforts, over the last month the virus has begun circulating outside of China in multiple countries and territories.

Cases have now appeared in the United States involving some affected individuals who haven’t traveled recently outside the country. They also have had no known contact with others who have recently arrived from China or other countries where the virus is spreading. The NIH and other U.S. public health agencies stand on high alert and have mobilized needed resources to help not only in its containment, but in the development of life-saving interventions.

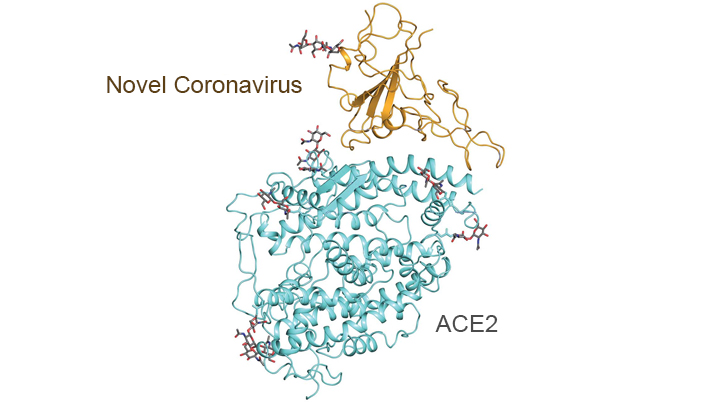

On the treatment and prevention front, some encouraging news was recently reported. In record time, an NIH-funded team of researchers has created the first atomic-scale map of a promising protein target for vaccine development [1]. This is the so-called spike protein on the new coronavirus that causes COVID-19. As shown above, a portion of this spiky surface appendage (green) allows the virus to bind a receptor on human cells, causing other portions of the spike to fuse the viral and human cell membranes. This process is needed for the virus to gain entry into cells and infect them.

Preclinical studies in mice of a candidate vaccine based on this spike protein are already underway at NIH’s Vaccine Research Center (VRC), part of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID). An early-stage phase I clinical trial of this vaccine in people is expected to begin within weeks. But there will be many more steps after that to test safety and efficacy, and then to scale up to produce millions of doses. Even though this timetable will potentially break all previous speed records, a safe and effective vaccine will take at least another year to be ready for widespread deployment.

Coronaviruses are a large family of viruses, including some that cause “the common cold” in healthy humans. In fact, these viruses are found throughout the world and account for up to 30 percent of upper respiratory tract infections in adults.

This outbreak of COVID-19 marks the third time in recent years that a coronavirus has emerged to cause severe disease and death in some people. Earlier coronavirus outbreaks included SARS (severe acute respiratory syndrome), which emerged in late 2002 and disappeared two years later, and MERS (Middle East respiratory syndrome), which emerged in 2012 and continues to affect people in small numbers.

Soon after COVID-19 emerged, the new coronavirus, which is closely related to SARS, was recognized as its cause. NIH-funded researchers including Jason McLellan, an alumnus of the VRC and now at The University of Texas at Austin, were ready. They’d been studying coronaviruses in collaboration with NIAID investigators for years, with special attention to the spike proteins.

Just two weeks after Chinese scientists reported the first genome sequence of the virus [2], McLellan and his colleagues designed and produced samples of its spike protein. Importantly, his team had earlier developed a method to lock coronavirus spike proteins into a shape that makes them both easier to analyze structurally via the high-resolution imaging tool cryo-electron microscopy and to use in vaccine development efforts.

After locking the spike protein in the shape it takes before fusing with a human cell to infect it, the researchers reconstructed its atomic-scale 3D structural map in just 12 days. Their results, published in Science, confirm that the spike protein on the virus that causes COVID-19 is quite similar to that of its close relative, the SARS virus. It also appears to bind human cells more tightly than the SARS virus, which may help to explain why the new coronavirus appears to spread more easily from person to person, mainly by respiratory transmission.

McLellan’s team and his NIAID VRC counterparts also plan to use the stabilized spike protein as a probe to isolate naturally produced antibodies from people who’ve recovered from COVID-19. Such antibodies might form the basis of a treatment for people who’ve been exposed to the virus, such as health care workers.

The NIAID is now working with the biotechnology company Moderna, Cambridge, MA, to use the latest findings to develop a vaccine candidate using messenger RNA (mRNA), molecules that serve as templates for making proteins. The goal is to direct the body to produce a spike protein in such a way to elicit an immune response and the production of antibodies. An early clinical trial of the vaccine in people is expected to begin in the coming weeks. Other vaccine candidates are also in preclinical development.

Meanwhile, the first clinical trial in the U.S. to evaluate an experimental treatment for COVID-19 is already underway at the University of Nebraska Medical Center’s biocontainment unit [3]. The NIH-sponsored trial will evaluate the safety and efficacy of the experimental antiviral drug remdesivir in hospitalized adults diagnosed with COVID-19. The first participant is an American who was repatriated after being quarantined on the Diamond Princess cruise ship in Japan.

As noted, the risk of contracting COVID-19 in the United States is currently low, but the situation is changing rapidly. One of the features that makes the virus so challenging to stay in front of is its long latency period before the characteristic flu-like fever, cough, and shortness of breath manifest. In fact, people infected with the virus may not show any symptoms for up to two weeks, allowing them to pass it on to others in the meantime. You can track the reported cases in the United States on the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s website.

As the outbreak continues over the coming weeks and months, you can be certain that NIH and other U.S. public health organizations are working at full speed to understand this virus and to develop better diagnostics, treatments, and vaccines.

References:

[1] Cryo-EM structure of the 2019-nCoV spike in the prefusion conformation. Wrapp D, Wang N, Corbett KS, Goldsmith JA, Hsieh CL, Abiona O, Graham BS, McLellan JS. Science. 2020 Feb 19.

[2] A new coronavirus associated with human respiratory disease in China. Wu F, Zhao S, Yu B, Chen YM, Wang W, Song ZG, Hu Y, Tao ZW, Tian JH, Pei YY, Yuan ML, Zhang YL, Dai FH, Liu Y, Wang QM, Zheng JJ, Xu L, Holmes EC, Zhang YZ. Nature. 2020 Feb 3.

[3] NIH clinical trial of remdesivir to treat COVID-19 begins. NIH News Release. Feb 25, 2020.

Links:

Coronaviruses (National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases/NIH)

Coronavirus (COVID-19) (NIAID)

Coronavirus Disease 2019 (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta)

NIH Support: National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases

Battling Malaria at the Atomic Level

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Tropical medicine has its share of wily microbes. Among the most clever is the mosquito-borne protozoan Plasmodium falciparum, which is the cause of the most common—and most lethal—form of malaria. For decades, doctors have used antimalarial drugs against P. falciparum. But just when malaria appeared to be well on its way to eradication, this parasitic protozoan mutated in ways that has enabled it to resist frontline antimalarial drugs. This resistance is a major reason that malaria, one of the world’s oldest diseases, still claims the lives of about 400,000 people each year [1].

This is a situation with which I have personal experience. Thirty years ago before traveling to Nigeria, I followed directions and took chloroquine to prevent malaria. But the resistance to the drug was already widespread, and I came down with malaria anyway. Fortunately, the parasite that a mosquito delivered to me was sensitive to another drug called Fansidar, which acts through another mechanism. I was pretty sick for a few days, but recovered without lasting consequences.

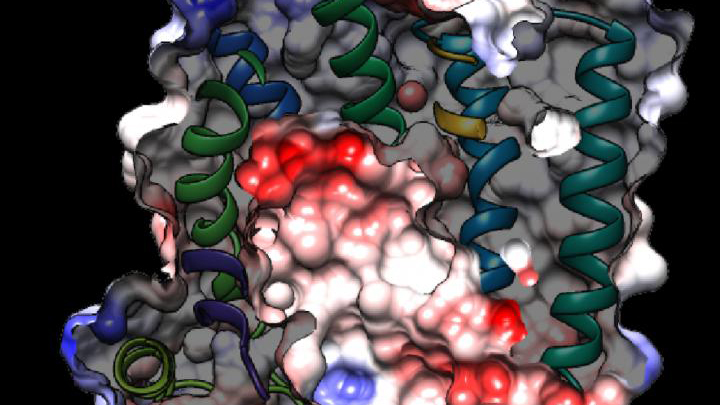

While new drugs are being developed to thwart P. falciparum, some researchers are busy developing tools to predict what mutations are likely to occur next in the parasite’s genome. And that’s what is so exciting about the image above. It presents the unprecedented, 3D atomic-resolution structure of a protein made by P. falciparum that’s been a major source of its resistance: the chloroquine-resistance transporter protein, or PfCRT.

In this cropped density map, you see part of the protein’s biochemical structure. The colorized area displays the long, winding chain of amino acids within the protein as helices in shades of green, blue and gold. These helices enclose a central cavity essential for the function of the protein, whose electrostatic properties are shown here as negative (red), positive (blue), and neutral (white). All this structural information was captured using cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM). The technique involves flash-freezing molecules in liquid nitrogen and bombarding them with electrons to capture their images with a special camera.

This groundbreaking work, published recently in Nature, comes from an NIH-supported multidisciplinary research team, led by David Fidock, Matthias Quick, and Filippo Mancia, Columbia University Irving Medical Center, New York [2]. It marks a major feat for structural biology, because PfCRT is on the small side for standard cryo-EM and, as Mancia discovered, the protein is almost featureless.

These two strikes made Mancia and colleagues wonder at first whether they would swing and miss at their attempt to image the protein. With the help of coauthor Anthony Kossiakoff, a researcher at the University of Chicago, the team complexed PfCRT to a bulkier antibody fragment. That doubled the size of their subject, and the fragment helped to draw out PfCRT’s hidden features. One year and a lot of hard work later, they got their homerun.

PfCRT is a transport protein embedded in the surface membrane of what passes for the gut of P. falciparum. Because the gene encoding it is highly mutable, the PfCRT protein modified its structure many years ago, enabling it to pump out and render ineffective several drugs in a major class of antimalarials called 4-aminoquinolines. That includes chloroquine.

Now, with the atomic structure in hand, researchers can map the locations of existing mutations and study how they work. This information will also allow them to model which regions of the protein to be on the lookout for the next adaptive mutations. The hope is this work will help to prolong the effectiveness of today’s antimalarial drugs.

For example, the drug piperaquine, a 4-aminoquinoline agent, is now used in combination with another antimalarial. The combination has proved quite effective. But recent reports show that P. falciparum has acquired resistance to piperaquine, driven by mutations in PfCRT that are spreading rapidly across Southeast Asia [3].

Interestingly, the researchers say they have already pinpointed single mutations that could confer piperaquine resistance to parasites from South America. They’ve also located where new mutations are likely to occur to compromise the drug’s action in Africa, where most malarial infections and deaths occur. So, this atomic structure is already being put to good use.

Researchers also hope that this model will allow drug designers to make structural adjustments to old, less effective malarial drugs and perhaps restore them to their former potency. Perhaps this could even be done by modifying chloroquine, introduced in the 1940s as the first effective antimalarial. It was used worldwide but was largely shelved a few decades later due to resistance—as I experienced three decades ago.

Malaria remains a constant health threat for millions of people living in subtropical areas of the world. Wouldn’t it be great to restore chloroquine to the status of a frontline antimalarial? The drug is inexpensive, taken orally, and safe. Through the power of science, its return is no longer out of the question.

References:

[1] World malaria report 2019. World Health Organization, December 4, 2019

[2] Structure and drug resistance of the Plasmodium falciparum transporter PfCRT. Kim J, Tan YZ, Wicht KJ, Erramilli SK, Dhingra SK, Okombo J, Vendome J, Hagenah LM, Giacometti SI, Warren AL, Nosol K, Roepe PD, Potter CS, Carragher B, Kossiakoff AA, Quick M, Fidock DA, Mancia F. Nature. 2019 Dec;576(7786):315-320.

[3] Determinants of dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine treatment failure in Plasmodium falciparum malaria in Cambodia, Thailand, and Vietnam: a prospective clinical, pharmacological, and genetic study. van der Pluijm RW, Imwong M, Chau NH, Hoa NT, et. al. Lancet Infect Dis. 2019 Sep;19(9):952-961.

Links:

Malaria (National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases/NIH)

Fidock Lab (Columbia University Irving Medical Center, New York)

Video: David Fidock on antimalarial drug resistance (BioMedCentral/YouTube)

Kossiakoff Lab (University of Chicago)

Mancia Lab (Columbia University Irving Medical Center)

Matthias Quick (Columbia University Irving Medical Center)

NIH Support: National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases; National Institute of General Medical Sciences; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute

Next Page