malaria

Battling Malaria at the Atomic Level

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Tropical medicine has its share of wily microbes. Among the most clever is the mosquito-borne protozoan Plasmodium falciparum, which is the cause of the most common—and most lethal—form of malaria. For decades, doctors have used antimalarial drugs against P. falciparum. But just when malaria appeared to be well on its way to eradication, this parasitic protozoan mutated in ways that has enabled it to resist frontline antimalarial drugs. This resistance is a major reason that malaria, one of the world’s oldest diseases, still claims the lives of about 400,000 people each year [1].

This is a situation with which I have personal experience. Thirty years ago before traveling to Nigeria, I followed directions and took chloroquine to prevent malaria. But the resistance to the drug was already widespread, and I came down with malaria anyway. Fortunately, the parasite that a mosquito delivered to me was sensitive to another drug called Fansidar, which acts through another mechanism. I was pretty sick for a few days, but recovered without lasting consequences.

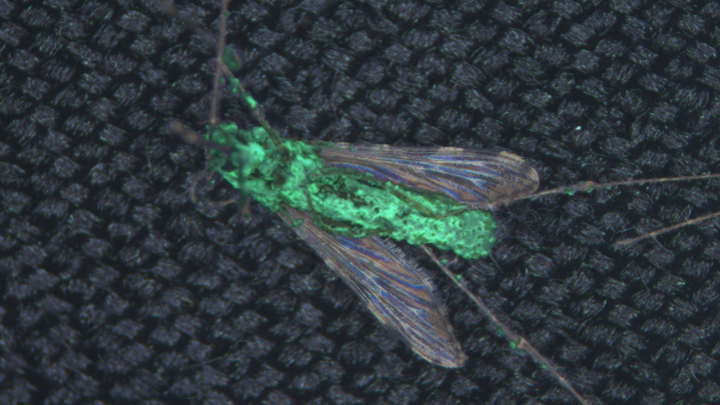

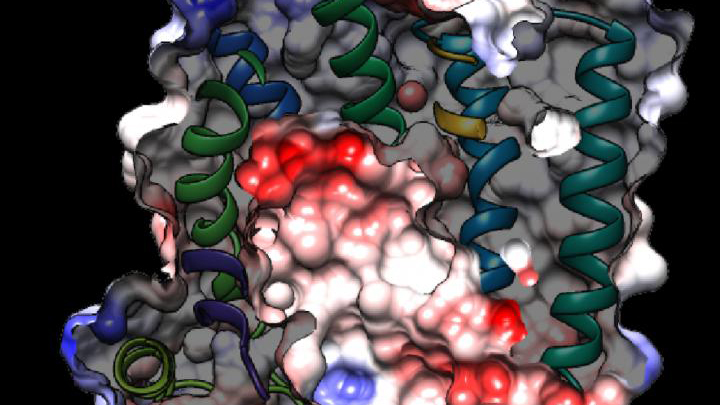

While new drugs are being developed to thwart P. falciparum, some researchers are busy developing tools to predict what mutations are likely to occur next in the parasite’s genome. And that’s what is so exciting about the image above. It presents the unprecedented, 3D atomic-resolution structure of a protein made by P. falciparum that’s been a major source of its resistance: the chloroquine-resistance transporter protein, or PfCRT.

In this cropped density map, you see part of the protein’s biochemical structure. The colorized area displays the long, winding chain of amino acids within the protein as helices in shades of green, blue and gold. These helices enclose a central cavity essential for the function of the protein, whose electrostatic properties are shown here as negative (red), positive (blue), and neutral (white). All this structural information was captured using cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM). The technique involves flash-freezing molecules in liquid nitrogen and bombarding them with electrons to capture their images with a special camera.

This groundbreaking work, published recently in Nature, comes from an NIH-supported multidisciplinary research team, led by David Fidock, Matthias Quick, and Filippo Mancia, Columbia University Irving Medical Center, New York [2]. It marks a major feat for structural biology, because PfCRT is on the small side for standard cryo-EM and, as Mancia discovered, the protein is almost featureless.

These two strikes made Mancia and colleagues wonder at first whether they would swing and miss at their attempt to image the protein. With the help of coauthor Anthony Kossiakoff, a researcher at the University of Chicago, the team complexed PfCRT to a bulkier antibody fragment. That doubled the size of their subject, and the fragment helped to draw out PfCRT’s hidden features. One year and a lot of hard work later, they got their homerun.

PfCRT is a transport protein embedded in the surface membrane of what passes for the gut of P. falciparum. Because the gene encoding it is highly mutable, the PfCRT protein modified its structure many years ago, enabling it to pump out and render ineffective several drugs in a major class of antimalarials called 4-aminoquinolines. That includes chloroquine.

Now, with the atomic structure in hand, researchers can map the locations of existing mutations and study how they work. This information will also allow them to model which regions of the protein to be on the lookout for the next adaptive mutations. The hope is this work will help to prolong the effectiveness of today’s antimalarial drugs.

For example, the drug piperaquine, a 4-aminoquinoline agent, is now used in combination with another antimalarial. The combination has proved quite effective. But recent reports show that P. falciparum has acquired resistance to piperaquine, driven by mutations in PfCRT that are spreading rapidly across Southeast Asia [3].

Interestingly, the researchers say they have already pinpointed single mutations that could confer piperaquine resistance to parasites from South America. They’ve also located where new mutations are likely to occur to compromise the drug’s action in Africa, where most malarial infections and deaths occur. So, this atomic structure is already being put to good use.

Researchers also hope that this model will allow drug designers to make structural adjustments to old, less effective malarial drugs and perhaps restore them to their former potency. Perhaps this could even be done by modifying chloroquine, introduced in the 1940s as the first effective antimalarial. It was used worldwide but was largely shelved a few decades later due to resistance—as I experienced three decades ago.

Malaria remains a constant health threat for millions of people living in subtropical areas of the world. Wouldn’t it be great to restore chloroquine to the status of a frontline antimalarial? The drug is inexpensive, taken orally, and safe. Through the power of science, its return is no longer out of the question.

References:

[1] World malaria report 2019. World Health Organization, December 4, 2019

[2] Structure and drug resistance of the Plasmodium falciparum transporter PfCRT. Kim J, Tan YZ, Wicht KJ, Erramilli SK, Dhingra SK, Okombo J, Vendome J, Hagenah LM, Giacometti SI, Warren AL, Nosol K, Roepe PD, Potter CS, Carragher B, Kossiakoff AA, Quick M, Fidock DA, Mancia F. Nature. 2019 Dec;576(7786):315-320.

[3] Determinants of dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine treatment failure in Plasmodium falciparum malaria in Cambodia, Thailand, and Vietnam: a prospective clinical, pharmacological, and genetic study. van der Pluijm RW, Imwong M, Chau NH, Hoa NT, et. al. Lancet Infect Dis. 2019 Sep;19(9):952-961.

Links:

Malaria (National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases/NIH)

Fidock Lab (Columbia University Irving Medical Center, New York)

Video: David Fidock on antimalarial drug resistance (BioMedCentral/YouTube)

Kossiakoff Lab (University of Chicago)

Mancia Lab (Columbia University Irving Medical Center)

Matthias Quick (Columbia University Irving Medical Center)

NIH Support: National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases; National Institute of General Medical Sciences; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute

Seven More Awesome Technologies Made Possible by Your Tax Dollars

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

We live in a world energized by technological advances, from that new app on your smartphone to drones and self-driving cars. As you can see from this video, NIH-supported researchers are also major contributors, developing a wide range of amazing biomedical technologies that offer tremendous potential to improve our health.

Produced by the NIH’s National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering (NIBIB), this video starts by showcasing some cool fluorescent markers that are custom-designed to light up specific cells in the body. This technology is already helping surgeons see and remove tumor cells with greater precision in people with head and neck cancer [1]. Further down the road, it might also be used to light up nerves, which can be very difficult to see—and spare—during operations for cancer and other conditions.

Other great things to come include:

- A wearable tattoo that detects alcohol levels in perspiration and wirelessly transmits the information to a smartphone.

- Flexible coils that produce high quality images during magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) [2-3]. In the future, these individualized, screen-printed coils may improve the comfort and decrease the scan times of people undergoing MRI, especially infants and small children.

- A time-release capsule filled with a star-shaped polymer containing the anti-malarial drug ivermectin. The capsule slowly dissolves in the stomach over two weeks, with the goal of reducing the need for daily doses of ivermectin to prevent malaria infections in at-risk people [4].

- A new radiotracer to detect prostate cancer that has spread to other parts of the body. Early clinical trial results show the radiotracer, made up of carrier molecules bonded tightly to a radioactive atom, appears to be safe and effective [5].

- A new supercooling technique that promises to extend the time that organs donated for transplantation can remain viable outside the body [6-7]. For example, current technology can preserve donated livers outside the body for just 24 hours. In animal studies, this new technique quadruples that storage time to up to four days.

- A wearable skin patch with dissolvable microneedles capable of effectively delivering an influenza vaccine. This painless technology, which has produced promising early results in humans, may offer a simple, affordable alternative to needle-and-syringe immunization [8].

If you like what you see here, be sure to check out this previous NIH video that shows six more awesome biomedical technologies that your tax dollars are helping to create. So, let me extend a big thanks to you from those of us at NIH—and from all Americans who care about the future of their health—for your strong, continued support!

References:

[1] Image-guided surgery in cancer: A strategy to reduce incidence of positive surgical margins. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Syst Biol Med. 2018 Feb 23.

[2] Screen-printed flexible MRI receive coils. Corea JR, Flynn AM, Lechêne B, Scott G, Reed GD, Shin PJ, Lustig M, Arias AC. Nat Commun. 2016 Mar 10;7:10839.

[3] Printed Receive Coils with High Acoustic Transparency for Magnetic Resonance Guided Focused Ultrasound. Corea J, Ye P, Seo D, Butts-Pauly K, Arias AC, Lustig M. Sci Rep. 2018 Feb 21;8(1):3392.

[4] Oral, ultra-long-lasting drug delivery: Application toward malaria elimination goals. Bellinger AM, Jafari M1, Grant TM, Zhang S, Slater HC, Wenger EA, Mo S, Lee YL, Mazdiyasni H, Kogan L, Barman R, Cleveland C, Booth L, Bensel T, Minahan D, Hurowitz HM, Tai T, Daily J, Nikolic B, Wood L, Eckhoff PA, Langer R, Traverso G. Sci Transl Med. 2016 Nov 16;8(365):365ra157.

[5] Clinical Translation of a Dual Integrin avb3– and Gastrin-Releasing Peptide Receptor–Targeting PET Radiotracer, 68Ga-BBN-RGD. Zhang J, Niu G, Lang L, Li F, Fan X, Yan X, Yao S, Yan W, Huo L, Chen L, Li Z, Zhu Z, Chen X. J Nucl Med. 2017 Feb;58(2):228-234.

[6] Supercooling enables long-term transplantation survival following 4 days of liver preservation. Berendsen TA, Bruinsma BG, Puts CF, Saeidi N, Usta OB, Uygun BE, Izamis ML, Toner M, Yarmush ML, Uygun K. Nat Med. 2014 Jul;20(7):790-793.

[7] The promise of organ and tissue preservation to transform medicine. Giwa S, Lewis JK, Alvarez L, Langer R, Roth AE, et a. Nat Biotechnol. 2017 Jun 7;35(6):530-542.

[8] The safety, immunogenicity, and acceptability of inactivated influenza vaccine delivered by microneedle patch (TIV-MNP 2015): a randomised, partly blinded, placebo-controlled, phase 1 trial. Rouphael NG, Paine M, Mosley R, Henry S, McAllister DV, Kalluri H, Pewin W, Frew PM, Yu T, Thornburg NJ, Kabbani S, Lai L, Vassilieva EV, Skountzou I, Compans RW, Mulligan MJ, Prausnitz MR; TIV-MNP 2015 Study Group.

Links:

National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering (NIH)

Center for Wearable Sensors (University of California, San Diego)

Hyperpolarized MRI Technology Resource Center (University of California, San Francisco)

Center for Engineering in Medicine (Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston)

Center for Drug Design, Development and Delivery (Georgia Tech University, Atlanta)

NIH Support: National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering; National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases

Tagging Essential Malaria Genes to Advance Drug Development

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

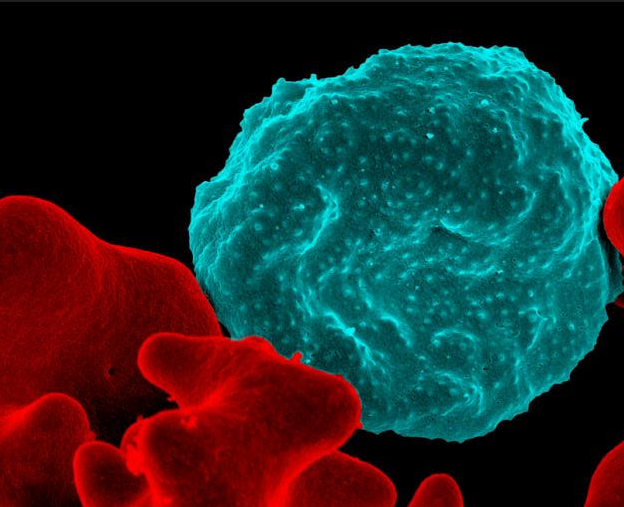

Caption: Colorized scanning electron micrograph of a blood cell infected with malaria parasites (blue with dots) surrounded by uninfected cells (red).

Credit: National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, NIH

As a volunteer physician in a small hospital in Nigeria 30 years ago, I was bitten by lots of mosquitoes and soon came down with headache, chills, fever, and muscle aches. It was malaria. Fortunately, the drug available to me then was effective, but I was pretty sick for a few days. Since that time, malarial drug resistance has become steadily more widespread. In fact, the treatment that cured me would be of little use today. Combination drug therapies including artemisinin have been introduced to take the place of the older drugs [1], but experts are concerned the mosquito-borne parasites that cause malaria are showing signs of drug resistance again.

So, researchers have been searching the genome of Plasmodium falciparum, the most-lethal species of the malaria parasite, for potentially better targets for drug or vaccine development. You wouldn’t think such work would be too tough because the genome of P. falciparum was sequenced more than 15 years ago [2]. Yet it’s proven to be a major challenge because the genetic blueprint of this protozoan parasite has an unusual bias towards two nucleotides (adenine and thymine), which makes it difficult to use standard research tools to study the functions of its genes.

Now, using a creative new spin on an old technique, an NIH-funded research team has solved this difficult problem and, for the first time, completely characterized the genes in the P. falciparum genome [3]. Their work identified 2,680 genes essential to P. falciparum’s growth and survival in red blood cells, where it does the most damage in humans. This gene list will serve as an important guide in the years ahead as researchers seek to identify the equivalent of a malarial Achilles heel, and use that to develop new and better ways to fight this deadly tropical disease.

Creative Minds: Building a CRISPR Gene Drive Against Malaria

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Valentino Gantz/Credit: Erik Jepsen

Researchers have used Drosophila melanogaster, the common fruit fly that sometimes hovers around kitchens, to make seminal discoveries involving genetics, the nervous system, and behavior, just to name a few. Could a new life-saving approach to prevent malaria be next? Valentino Gantz, a researcher at the University of California, San Diego, is on a path to answer that question.

Gantz has received a 2016 NIH Director’s Early Independence Award to use Drosophila to hone a new bioengineered tool that acts as a so-called “gene drive,” which spreads a new genetically encoded trait through a population much faster than would otherwise be possible. The lessons learned while working with flies will ultimately be applied to developing a more foolproof system for use in mosquitoes with the hope of stopping the transmission of malaria and potentially other serious mosquito-borne diseases.

Snapshots of Life: Neurons in a New Light

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Birds do it, bees do it, and even educated fleas do it. No, not fall in love, as the late Ella Fitzgerald so famously sang. Birds and insects can see polarized light—that is, light waves transmitted in a single directional plane—in ways that provides them with a far more colorful and detailed view of the world than is possible with the human eye.

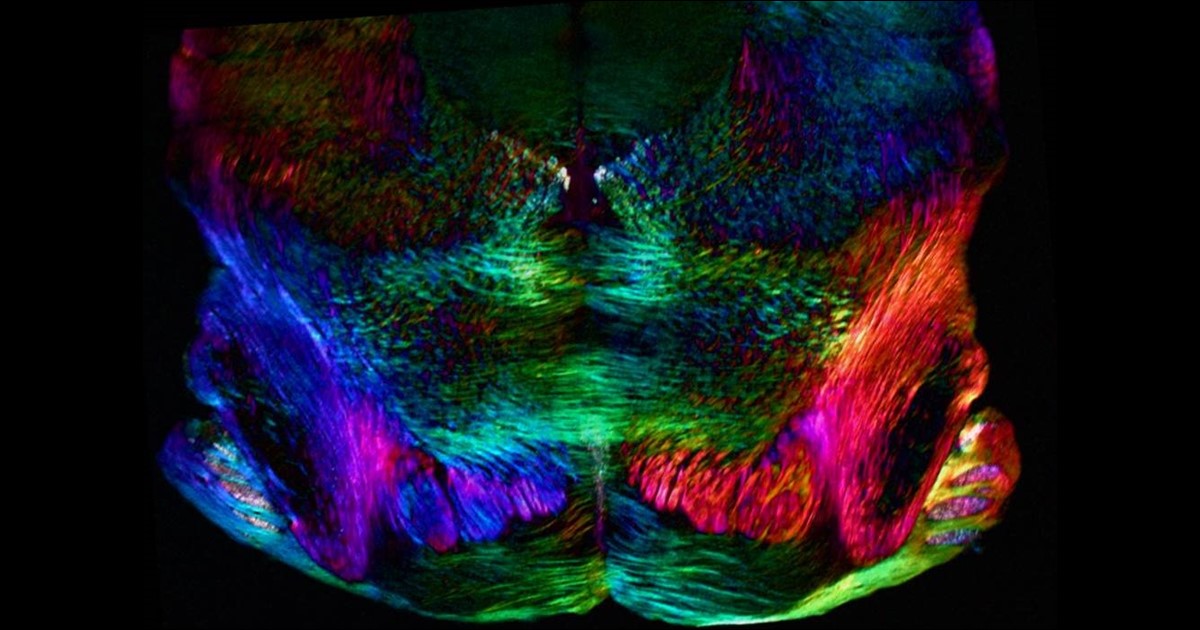

Still, thanks to innovations in microscope technology, scientists have been able to tap into the power of polarized light vision to explore the inner workings of many complex biological systems, including the brain. In this image, researchers used a recently developed polarized light microscope to trace the spatial orientation of neurons in a thin section of the mouse midbrain. Neurons that stretch horizontally appear green, while those oriented at a 45-degree angle are pinkish-red and those at 225 degrees are purplish-blue. What’s amazing is that these colors don’t involve staining or tagging the cells with fluorescent markers: the colors are generated strictly from the light interacting with the physical orientation of each neuron.

Gene Drive Research Takes Aim at Malaria

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Malaria has afflicted humans for millennia. Even today, the mosquito-borne, parasitic disease claims more than a half-million lives annually [1]. Now, in a study that has raised both hope and concern, researchers have taken aim at this ancient scourge by using one of modern science’s most powerful new technologies—the CRISPR/Cas9 gene-editing tool—to turn mosquitoes from dangerous malaria vectors into allies against infection [2].

Malaria has afflicted humans for millennia. Even today, the mosquito-borne, parasitic disease claims more than a half-million lives annually [1]. Now, in a study that has raised both hope and concern, researchers have taken aim at this ancient scourge by using one of modern science’s most powerful new technologies—the CRISPR/Cas9 gene-editing tool—to turn mosquitoes from dangerous malaria vectors into allies against infection [2].

The secret behind this new strategy is the “gene drive,” which involves engineering an organism’s genome in a way that intentionally spreads, or drives, a trait through its population much faster than is possible by normal Mendelian inheritance. The concept of gene drive has been around since the late 1960s [3]; but until the recent arrival of highly precise gene editing tools like CRISPR/Cas9, the approach was largely theoretical. In the new work, researchers inserted into a precise location in the mosquito chromosome, a recombinant DNA segment designed to block transmission of malaria parasites. Importantly, this segment also contained a gene drive designed to ensure the trait was inherited with extreme efficiency. And efficient it was! When the gene-drive engineered mosquitoes were mated with normal mosquitoes in the lab, they passed on the malaria-blocking trait to 99.5 percent of their offspring (as opposed to 50 percent for Mendelian inheritance).

LabTV: Curious About Malaria

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

It’s the time of year when thoughts turn to buying school supplies and heading back to the classroom or off to university. So, throughout the month of August, I’ll be sharing LabTV profiles of young people whose learning experiences have set them on the path to becoming biomedical researchers.

It’s the time of year when thoughts turn to buying school supplies and heading back to the classroom or off to university. So, throughout the month of August, I’ll be sharing LabTV profiles of young people whose learning experiences have set them on the path to becoming biomedical researchers.

One of the great things about college is that you never know where those four years might lead you. Elyse Munoz, who’s the focus of today’s video, offers an excellent case in point. Upon enrolling at Arizona State University, Tempe, she chose political science as her major—only to find the classes “incredibly boring.” Then a friend talked Munoz into taking an anatomy class, and suddenly everything clicked: she discovered biology was her true calling.

Now, Munoz is a candidate for a Ph.D. in genetics at Pennsylvania State University, State College. Working in the lab of molecular parasitologist Scott Lindner, Munoz is contributing to the search for promising vaccine targets for malaria, a mosquito-borne disease that kills more than a half-million people, mainly children under the age of 5, around the globe each year.

Malaria Vaccine Shows Promise

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Courtesy of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, NIH

Malaria has confounded biomedical researchers for decades because it’s been impossible so far to develop a vaccine that offers a high level of protection. But, thanks to a different approach to vaccine design and delivery, there’s hope that we may have finally turned the corner in the fight against this mosquito-borne health threat.

Fighting Malaria, With a Little Help from Bacteria

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Caption: Anopheles female blood feeding and Plasmodium falciparum eggs in Anopheles mosquito midguts.

Credit: Image courtesy of Jose Luis Ramirez, Laboratory of Malaria and Vector Research, NIAID, NIH

It turns out that one of the most innovative and effective strategies to fight malaria might involve harnessing a bacterium called Wolbachia. This naturally occurring genus of bacteria infects many species of insects, including mosquitoes. The reason this is important is that Wolbachia-infected mosquitoes become resistant to the parasite Plasmodium falciparum, which causes some 219 million cases of malaria worldwide and more than 660,000 deaths [1]. Wouldn’t it be amazing if Wolbachia-infected mosquitoes blocked the transmission of malaria?

Unfortunately, Wolbachia don’t normally pass from generation to generation in Anopheles, the mosquitoes that spread malaria. But that hurdle has now been overcome.