West Africa

Celebrating 2019 Biomedical Breakthroughs

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Happy New Year! As we say goodbye to the Teens, let’s take a look back at 2019 and some of the groundbreaking scientific discoveries that closed out this remarkable decade.

Each December, the reporters and editors at the journal Science select their breakthrough of the year, and the choice for 2019 is nothing less than spectacular: An international network of radio astronomers published the first image of a black hole, the long-theorized cosmic singularity where gravity is so strong that even light cannot escape [1]. This one resides in a galaxy 53 million light-years from Earth! (A light-year equals about 6 trillion miles.)

Though the competition was certainly stiff in 2019, the biomedical sciences were well represented among Science’s “runner-up” breakthroughs. They include three breakthroughs that have received NIH support. Let’s take a look at them:

In a first, drug treats most cases of cystic fibrosis: Last October, two international research teams reported the results from phase 3 clinical trials of the triple drug therapy Trikafta to treat cystic fibrosis (CF). Their data showed Trikafta effectively compensates for the effects of a mutation carried by about 90 percent of people born with CF. Upon reviewing these impressive data, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved Trikafta, developed by Vertex Pharmaceuticals.

The approval of Trikafta was a wonderful day for me personally, having co-led the team that isolated the CF gene 30 years ago. A few years later, I wrote a song called “Dare to Dream” imagining that wonderful day when “the story of CF is history.” Though we’ve still got more work to do, we’re getting a lot closer to making that dream come true. Indeed, with the approval of Trikafta, most people with CF have for the first time ever a real chance at managing this genetic disease as a chronic condition over the course of their lives. That’s a tremendous accomplishment considering that few with CF lived beyond their teens as recently as the 1980s.

Such progress has been made possible by decades of work involving a vast number of researchers, many funded by NIH, as well as by more than two decades of visionary and collaborative efforts between the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation and Aurora Biosciences (now, Vertex) that built upon that fundamental knowledge of the responsible gene and its protein product. Not only did this innovative approach serve to accelerate the development of therapies for CF, it established a model that may inform efforts to develop therapies for other rare genetic diseases.

Hope for Ebola patients, at last: It was just six years ago that news of a major Ebola outbreak in West Africa sounded a global health emergency of the highest order. Ebola virus disease was then recognized as an untreatable, rapidly fatal illness for the majority of those who contracted it. Though international control efforts ultimately contained the spread of the virus in West Africa within about two years, over 28,600 cases had been confirmed leading to more than 11,000 deaths—marking the largest known Ebola outbreak in human history. Most recently, another major outbreak continues to wreak havoc in northeastern Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), where violent civil unrest is greatly challenging public health control efforts.

As troubling as this news remains, 2019 brought a needed breakthrough for the millions of people living in areas susceptible to Ebola outbreaks. A randomized clinical trial in the DRC evaluated four different drugs for treating acutely infected individuals, including an antibody against the virus called mAb114, and a cocktail of anti-Ebola antibodies referred to as REGN-EB3. The trial’s preliminary data showed that about 70 percent of the patients who received either mAb114 or the REGN-EB3 antibody cocktail survived, compared with about half of those given either of the other two medicines.

So compelling were these preliminary results that the trial, co-sponsored by NIH’s National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) and the DRC’s National Institute for Biomedical Research, was halted last August. The results were also promptly made public to help save lives and stem the latest outbreak. All Ebola patients in the DRC treatment centers now are treated with one or the other of these two options. The trial results were recently published.

The NIH-developed mAb114 antibody and the REGN-EB3 cocktail are the first therapeutics to be shown in a scientifically rigorous study to be effective at treating Ebola. This work also demonstrates that ethically sound clinical research can be conducted under difficult conditions in the midst of a disease outbreak. In fact, the halted study was named Pamoja Tulinde Maisha (PALM), which means “together save lives” in Kiswahili.

To top off the life-saving progress in 2019, the FDA just approved the first vaccine for Ebola. Called Ervebo (earlier rVSV-ZEBOV), this single-dose injectable vaccine is a non-infectious version of an animal virus that has been genetically engineered to carry a segment of a gene from the Zaire species of the Ebola virus—the virus responsible for the current DRC outbreak and the West Africa outbreak. Because the vaccine does not contain the whole Zaire virus, it can’t cause Ebola. Results from a large study in Guinea conducted by the WHO indicated that the vaccine offered substantial protection against Ebola virus disease. Ervebo, produced by Merck, has already been given to over 259,000 individuals as part of the response to the DRC outbreak. The NIH has supported numerous clinical trials of the vaccine, including an ongoing study in West Africa.

Microbes combat malnourishment: Researchers discovered a few years ago that abnormal microbial communities, or microbiomes, in the intestine appear to contribute to childhood malnutrition. An NIH-supported research team followed up on this lead with a study of kids in Bangladesh, and it published last July its groundbreaking finding: that foods formulated to repair the “gut microbiome” helped malnourished kids rebuild their health. The researchers were able to identify a network of 15 bacterial species that consistently interact in the gut microbiomes of Bangladeshi children. In this month-long study, this bacterial network helped the researchers characterize a child’s microbiome and/or its relative state of repair.

But a month isn’t long enough to determine how the new foods would help children grow and recover. The researchers are conducting a similar study that is much longer and larger. Globally, malnutrition affects an estimated 238 million children under the age 5, stunting their normal growth, compromising their health, and limiting their mental development. The hope is that these new foods and others adapted for use around the world soon will help many more kids grow up to be healthy adults.

Measles Resurgent: The staff at Science also listed their less-encouraging 2019 Breakdowns of the Year, and unfortunately the biomedical sciences made the cut with the return of measles in the U.S. Prior to 1963, when the measles vaccine was developed, 3 to 4 million Americans were sickened by measles each year. Each year about 500 children would die from measles, and many more would suffer lifelong complications. As more people were vaccinated, the incidence of measles plummeted. By the year 2000, the disease was even declared eliminated from the U.S.

But, as more parents have chosen not to vaccinate their children, driven by the now debunked claim that vaccines are connected to autism, measles has made a very preventable comeback. Last October, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported an estimated 1,250 measles cases in the United States at that point in 2019, surpassing the total number of cases reported annually in each of the past 25 years.

The good news is those numbers can be reduced if more people get the vaccine, which has been shown repeatedly in many large and rigorous studies to be safe and effective. The CDC recommends that children should receive their first dose by 12 to 15 months of age and a second dose between the ages of 4 and 6. Older people who’ve been vaccinated or have had the measles previously should consider being re-vaccinated, especially if they live in places with low vaccination rates or will be traveling to countries where measles are endemic.

Despite this public health breakdown, 2019 closed out a memorable decade of scientific discovery. The Twenties will build on discoveries made during the Teens and bring us even closer to an era of precision medicine to improve the lives of millions of Americans. So, onward to 2020—and happy New Year!

Reference:

[1] 2019 Breakthrough of the Year. Science, December 19, 2019.

NIH Support: These breakthroughs represent the culmination of years of research involving many investigators and the support of multiple NIH institutes.

Ebola Virus: Lessons from a Unique Survivor

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

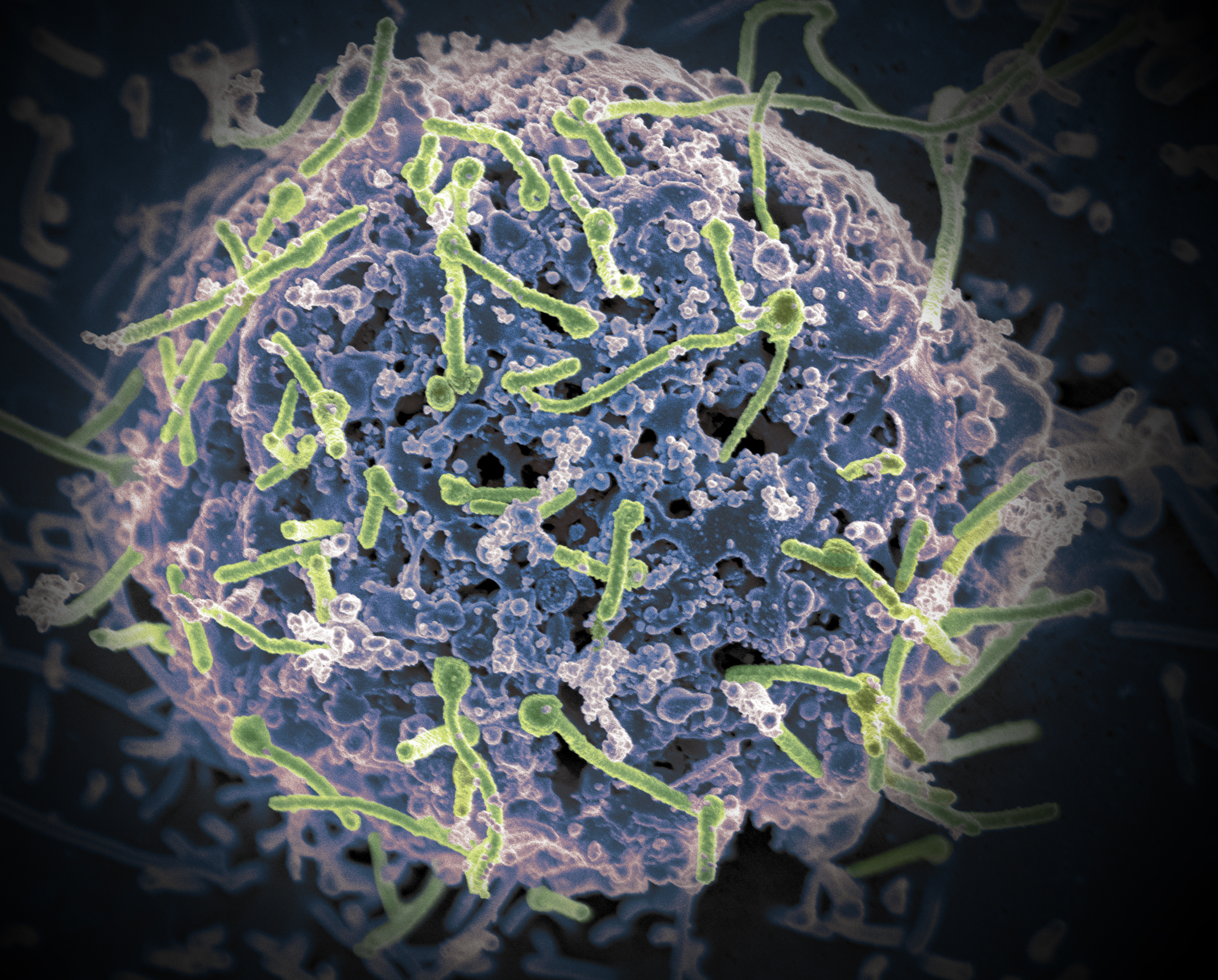

Caption: Ebola virus (green) is shown on cell surface.

Credit: National Institutes of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, NIH

There are new reports of an outbreak of Ebola virus disease in the Democratic Republic of Congo. This news comes just two years after international control efforts eventually contained an Ebola outbreak in West Africa, though before control was achieved, more than 11,000 people died—the largest known Ebola outbreak in human history [1]. While considerable progress continues to be made in understanding the infection and preparing for new outbreaks, many questions remain about why some people die from Ebola and others survive.

Now, some answers are beginning to emerge thanks to a new detailed analysis of the immune responses of a unique Ebola survivor, a 34-year-old American health-care worker who was critically ill and cared for at the NIH Special Clinical Studies Unit in 2015 [2]. The NIH-led team used the patient’s blood samples, which were drawn every day, to measure the number of viral particles and monitor how his immune system reacted over the course of his Ebola infection, from early symptoms through multiple organ failures and, ultimately, his recovery.

The researchers identified unexpectedly large shifts in immune responses that preceded observable improvements in the patient’s symptoms. The researchers say that, through further study and close monitoring of such shifts, health care workers may be able to develop more effective ways to care for Ebola patients.

H3Africa: Fostering Collaboration

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Caption: Pioneers in building Africa’s genomic research capacity; front, Charlotte Osafo (l) and Yemi Raji; back, David Burke (l) and Tom Glover.

Credit: University of Michigan, Ann Arbor

About a year ago, Tom Glover began sifting through a stack of applications from prospective students hoping to be admitted into the Master’s Degree Program in Human Genetics at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. Glover, the program’s director, got about halfway through the stack when he noticed applications from two physicians in West Africa: Charlotte Osafo from Ghana, and Yemi Raji from Nigeria. Both were kidney specialists in their 40s, and neither had formal training in genomics or molecular biology, which are normally requirements for entry into the program.

Glover’s first instinct was to disregard the applications. But he noticed the doctors were affiliated with the Human Heredity and Health in Africa (H3Africa) Initiative, which is co-supported by the Wellcome Trust and the National Institutes of Health Common Fund, and aims in part to build the expertise to carry out genomics research across the continent of Africa. (I am proud to have had a personal hand in the initial steps that led to the founding of H3Africa.) Glover held onto the two applications and, after much internal discussion, Osafo and Raji were admitted to the Master’s Program. But there were important stipulations: they had to arrive early to undergo “boot camp” in genomics and molecular biology and also extend their coursework over an extra term.

Enlisting mHealth in the Fight Against River Blindness

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

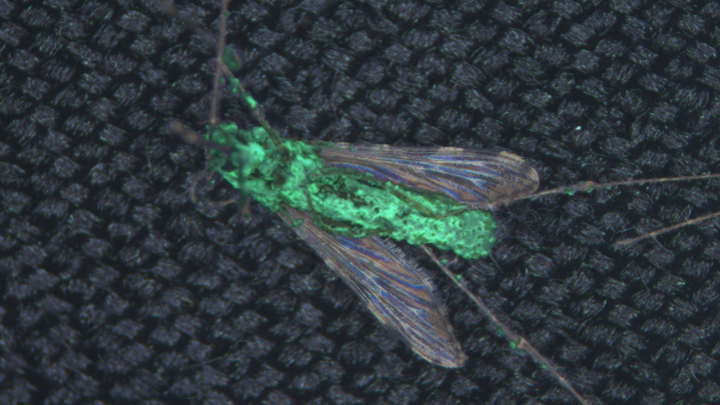

When it comes to devising new ways to provide state-of-the art medical care to people living in remote areas of the world, smartphones truly are helping scientists get smarter. For example, an NIH-supported team working in Central Africa recently turned an iPhone into a low-cost video microscope capable of quickly testing to see if people infected with a parasitic worm called Loa loa can safely receive a drug intended to protect them from a different, potentially blinding parasitic disease.

As shown in the video above, the iPhone’s camera scans a drop of a person’s blood for the movement of L. loa worms. Customized software then processes the motion to count the worms (see the dark circles) in the blood sample and arrive at an estimate of the body’s total worm load. The higher the worm load, the greater the risk of developing serious side effects from a drug treatment for river blindness, also known as onchocerciasis.

From Ebola Researchers, An Anthem of Hope

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

After watching this music video, you might wonder what on earth it has to do with biomedical science, let alone Ebola research. The answer is everything.

This powerful song, entitled “One Truth,” is dedicated to all of the brave researchers, healthcare workers, and others who have put their lives on the line to save people during the recent outbreak of Ebola virus disease. What’s more, it was written and performed by seven amazing scientists—one from the United States and six from West Africa.

NIH Ebola Update: Working Toward Treatments and Vaccines

Posted on by Drs. Anthony S. Fauci and Francis S. Collins

Updated Oct. 22, 2014: The National Institutes of Health (NIH) today announced the start of human clinical trials of a second Ebola vaccine candidate at the NIH Clinical Center in Bethesda, MD. In this early phase trial, researchers from NIH’s National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) are evaluating the vaccine, called VSV-ZEBOV, for its safety and ability to generate an immune response in healthy adults who receive two intramuscular doses, called a prime-boost strategy.

The Walter Reed Army Institute of Research is simultaneously testing the vaccine candidate as a single dose at its Clinical Trials Center in Silver Spring, MD. VSV-ZEBOV, which was developed by researchers at the Public Health Agency of Canada’s National Microbiology Laboratory, has been licensed to NewLink Genetics Corp. through its wholly owned subsidiary BioProtection Systems, both based in Ames, Iowa.

Early human testing of another Ebola vaccine candidate, co-developed by NIAID and GlaxoSmithKline, began in early September at the NIH Clinical Center. Initial data on that vaccine’s safety and ability to generate an immune response are expected by the end of 2014.

We are all alarmed by the scope and scale of the human tragedy occurring in West African nations affected by the Ebola virus disease epidemic. While the cornerstones of the Ebola response remain prompt diagnosis and isolation of patients, tracing of contacts, and proper protective equipment for healthcare workers, the National Institutes of Health (NIH), led by its National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), is spearheading efforts to develop treatments and a vaccine for Ebola as quickly as possible.

For example, NIAID has supported and collaborated with Mapp Biopharmaceutical, Inc., San Diego, in its development of the product known as ZMapp, which has been administered experimentally to several Ebola-infected patients. While it is not possible at this time to determine whether ZMapp benefited these patients, NIAID is supporting a broader effort to advance development and clinical testing of ZMapp to determine if it is safe and effective. In addition, the U.S. Biodefense Advanced Research and Development Agency (BARDA) has announced plans to optimize and accelerate the manufacturing of ZMapp, which is in limited supply, to enable clinical safety testing to proceed as soon as possible.

Using Genomics to Follow the Path of Ebola

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Caption: Colorized scanning electron micrograph of filamentous Ebola virus particles (blue) budding from a chronically infected VERO E6 cell (yellow-green).

Credit: National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, NIH

Long before the current outbreak of Ebola Virus Disease (EVD) began in West Africa, NIH-funded scientists had begun collaborating with labs in Sierra Leone and Nigeria to analyze the genomes and develop diagnostic tests for the virus that caused Lassa fever, a deadly hemorrhagic disease related to EVD. But when the outbreak struck in February 2014, an international team led by NIH Director’s New Innovator Awardee Pardis Sabeti quickly switched gears to focus on Ebola.

In a study just out in the journal Science [1], this fast-acting team reported that it has sequenced the complete genetic blueprints, or genomes, of 99 Ebola virus samples obtained from 78 patients in Sierra Leone. This new genomic data has revealed clues about the origin and evolution of the Ebola virus, as well as provided insights that may aid in the development of better diagnostics and inform efforts to devise effective therapies and vaccines.

Eradicating Ebola: In U.S. Biomedical Research, We Trust

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Caption: Researcher inside a biosafety level 4 laboratory, which provides the necessary precautions for working with the Ebola virus.

Credit: National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, NIH

Updated August 28, 2014: Today, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) announced plans to begin initial human testing of an investigational vaccine to prevent Ebola virus disease. Testing of the vaccine, co-developed by NIH’s National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) and GlaxoSmithKline, will begin next week at the NIH Clinical Center in Bethesda, MD.

As the outbreak of Ebola Virus Disease continues to spread in West Africa, now affecting four countries in the region, I am reminded how fragile life is—and how important NIH’s role is in protecting it.

NIH research has helped us understand how Ebola initially infects people and how it spreads from person to person. Preventing this spread is currently our greatest defense in fighting it. Through research, we know that the Ebola virus is transmitted through direct contact with bodily fluids and is not transmitted through the air like the flu. We also know the symptoms of Ebola and the period during which they can appear. This knowledge has informed how we manage the disease. We know that the virus can be contained and eradicated with early identification, isolation, strict infection control, and meticulous medical care.