infectious disease

Encouraging First-in-Human Results for a Promising HIV Vaccine

Posted on by Lawrence Tabak, D.D.S., Ph.D.

In recent years, we’ve witnessed some truly inspiring progress in vaccine development. That includes the mRNA vaccines that were so critical during the COVID-19 pandemic, the first approved vaccine for respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), and a “universal flu vaccine” candidate that could one day help to thwart future outbreaks of more novel influenza viruses.

Inspiring progress also continues to be made toward a safe and effective vaccine for HIV, which still infects about 1.5 million people around the world each year [1]. A prime example is the recent first-in-human trial of an HIV vaccine made in the lab from a unique protein nanoparticle, a molecular construct measuring just a few billionths of a meter.

The results of this early phase clinical study, published recently in the journal Science Translational Medicine [2] and earlier in Science [3], showed that the experimental HIV nanoparticle vaccine is safe in people. While this vaccine alone will not offer HIV protection and is intended to be part of an eventual broader, multistep vaccination regimen, the researchers also determined that it elicited a robust immune response in nearly all 36 healthy adult volunteers.

How robust? The results show that the nanoparticle vaccine, known by the lab name eOD-GT8 60-mer, successfully expanded production of a rare type of antibody-producing immune B cell in nearly all recipients.

What makes this rare type of B cell so critical is that it is the cellular precursor of other B cells capable of producing broadly neutralizing antibodies (bnAbs) to protect against diverse HIV variants. Also very good news, the vaccine elicited broad responses from helper T cells. They play a critical supportive role for those essential B cells and their development of the needed broadly neutralizing antibodies.

For decades, researchers have brought a wealth of ideas to bear on developing a safe and effective HIV vaccine. However, crossing the finish line—an FDA-approved vaccine—has proved profoundly difficult.

A major reason is the human immune system is ill equipped to recognize HIV and produce the needed infection-fighting antibodies. And yet the medical literature includes reports of people with HIV who have produced the needed antibodies, showing that our immune system can do it.

But these people remain relatively rare, and the needed robust immunity clocks in only after many years of infection. On top of that, HIV has a habit of mutating rapidly to produce a wide range of identity-altering variants. For a vaccine to work, it most likely will need to induce the production of bnAbs that recognize and defend against not one, but the many different faces of HIV.

To make the uncommon more common became the quest of a research team that includes scientists William Schief, Scripps Research and IAVI Neutralizing Antibody Center, La Jolla, CA; M. Juliana McElrath, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center, Seattle; and Kristen Cohen, a former member of the McElrath lab now at Moderna, Cambridge, MA. The team, with NIH collaborators and support, has been plotting out a stepwise approach to train the immune system into making the needed bnAbs that recognize many HIV variants.

The critical first step is to prime the immune system to make more of those coveted bnAb-precursor B cells. That’s where the protein nanoparticle known as eOD-GT8 60-mer enters the picture.

This nanoparticle, administered by injection, is designed to mimic a small, highly conserved segment of an HIV protein that allows the virus to bind and infect human cells. In the body, those nanoparticles launch an immune response and then quickly vanish. But because this important protein target for HIV vaccines is so tiny, its signal needed amplification for immune system detection.

To boost the signal, the researchers started with a bacterial protein called lumazine synthase (LumSyn). It forms the scaffold, or structural support, of the self-assembling nanoparticle. Then, they added to the LumSyn scaffold 60 copies of the key HIV protein. This louder HIV signal is tailored to draw out and engage those very specific B cells with the potential to produce bnAbs.

As the first-in-human study showed, the nanoparticle vaccine was safe when administered twice to each participant eight weeks apart. People reported only mild to moderate side effects that went away in a day or two. The vaccine also boosted production of the desired B cells in all but one vaccine recipient (35 of 36). The idea is that this increase in essential B cells sets the stage for the needed additional steps—booster shots that can further coax these cells along toward making HIV protective bnAbs.

The latest finding in Science Translational Medicine looked deeper into the response of helper T cells in the same trial volunteers. Again, the results appear very encouraging. The researchers observed CD4 T cells specific to the HIV protein and to the LumSyn in 84 percent and 93 percent of vaccine recipients. Their analyses also identified key hotspots that the T cells recognized, which is important information for refining future vaccines to elicit helper T cells.

The team reports that they’re now collaborating with Moderna, the developer of one of the two successful mRNA-based COVID-19 vaccines, on an mRNA version of eOD-GT8 60-mer. That’s exciting because mRNA vaccines are much faster and easier to produce and modify, which should now help to move this line of research along at a faster clip.

Indeed, two International AIDS Vaccine Initiative (IAVI)-sponsored clinical trials of the mRNA version are already underway, one in the U.S. and the other in Rwanda and South Africa [4]. It looks like this team and others are now on a promising track toward following the basic science and developing a multistep HIV vaccination regimen that guides the immune response and its stepwise phases in the right directions.

As we look back on more than 40 years of HIV research, it’s heartening to witness the progress that continues toward ending the HIV epidemic. This includes the recent FDA approval of the drug Apretude, the first injectable treatment option for pre-exposure prevention of HIV, and the continued global commitment to produce a safe and effective vaccine.

References:

[1] Global HIV & AIDS statistics fact sheet. UNAIDS.

[2] A first-in-human germline-targeting HIV nanoparticle vaccine induced broad and publicly targeted helper T cell responses. Cohen KW, De Rosa SC, Fulp WJ, deCamp AC, Fiore-Gartland A, Laufer DS, Koup RA, McDermott AB, Schief WR, McElrath MJ. Sci Transl Med. 2023 May 24;15(697):eadf3309.

[3] Vaccination induces HIV broadly neutralizing antibody precursors in humans. Leggat DJ, Cohen KW, Willis JR, Fulp WJ, deCamp AC, Koup RA, Laufer DS, McElrath MJ, McDermott AB, Schief WR. Science. 2022 Dec 2;378(6623):eadd6502.

[4] IAVI and Moderna launch first-in-Africa clinical trial of mRNA HIV vaccine development program. IAVI. May 18, 2022.

Links:

Progress Toward an Eventual HIV Vaccine, NIH Research Matters, Dec. 13, 2022.

NIH Statement on HIV Vaccine Awareness Day 2023, Auchincloss H, Kapogiannis, B. May, 18, 2023.

HIV Vaccine Development (National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases/NIH)

International AIDS Vaccine Initiative (IAVI) (New York, NY)

William Schief (Scripps Research, La Jolla, CA)

Julie McElrath (Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center, Seattle, WA)

McElrath Lab (Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center, Seattle, WA)

NIH Support: National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases

Tuberculosis: An Ancient Disease in Need of Modern Scientific Tools

Posted on by Anthony S. Fauci, M.D., National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases

Although COVID-19 has dominated our attention for the past two years, tuberculosis (TB), an ancient scourge, remains a dominating infectious disease globally, with an estimated 10 million new cases and more than 1.3 million deaths in 2020. TB disproportionately afflicts the poor and has long been the leading cause of death in people living with HIV.

Unfortunately, during the global COVID-19 pandemic, recent gains in TB control have been stalled or reversed. We’ve seen a massive drop in new TB diagnoses, reflecting poor access to care and an uptick in deaths in 2020 [1].

We are fighting TB with an armory of old weapons inferior to those we have for COVID-19. The Bacillus Calmette–Guérin (BCG) vaccine, the world’s only licensed TB vaccine, has been in use for more than 100 years. While BCG is somewhat effective at preventing TB meningitis in children, it provides more limited durable protection against pulmonary TB in children and adults. More effective vaccination strategies to prevent infection and disease, decrease relapse rates, and shorten durations of treatment are desperately needed to reduce the terrible global burden of TB.

In this regard, over the past five years, several exciting research advances have generated new optimism in the field of TB vaccinology. Non-human primate studies conducted at my National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases’ (NIAID) Vaccine Research Center and other NIAID-funded laboratories have demonstrated that effective immunity against infection is achievable and that administering BCG intravenously, rather than under the skin as it currently is given, is highly protective [2].

Results from a phase 2 trial testing BCG revaccination in adolescents at high risk of TB infection suggested this approach could help prevent TB [3]. In addition, a phase 2 trial of an experimental TB vaccine based on the recombinant protein M72 and an immune-priming adjuvant, AS01, also showed promise in preventing active TB disease in latently infected adults [4].

Both candidates are now moving on to phase 3 efficacy trials. The encouraging results of these trials, combined with nine other candidates currently in phase 2 or 3 studies [5], offer new hope that improved vaccines may be on the horizon. The NIAID is working with a team of other funders and investigators to analyze the correlates of protection from these studies to inform future TB vaccine development.

Even with these exciting developments, it is critical to accelerate our efforts to enhance and diversify the TB vaccine pipeline by addressing persistent basic and translational research gaps. To this end, NIAID has several new programs. The Immune Protection Against Mtb Centers are taking a multidisciplinary approach to integrate animal and human data to gain a comprehensive understanding of the immune responses required to prevent TB infection and disease.

This spring, NIAID will fund awards under the Innovation for TB Vaccine Discovery program that will focus on the discovery and early evaluation of novel TB vaccine candidates with the goal of diversifying the TB vaccine pipeline. Later this year, the Advancing Vaccine Adjuvant Research for TB program will systematically assess combinations of TB immunogens and adjuvants. Finally, NIAID’s well-established clinical trials networks are planning two new clinical trials of TB vaccine candidates.

As we look to the future, we must apply the lessons learned in the development of the COVID-19 vaccines to longstanding public health challenges such as TB. COVID-19 vaccine development was hugely successful due to the use of novel vaccine platforms, structure-based vaccine design, community engagement for rapid clinical trial enrollment, real-time data sharing with key stakeholders, and innovative trial designs.

However, critical gaps remain in our armamentarium. These include the harnessing the immunology of the tissues that line the respiratory tract to design vaccines more adept at blocking initial infection and transmission, employing thermostable formulations and novel delivery systems for resource-limited settings, and crafting effective messaging around vaccines for different populations.

As we work to develop better ways to prevent, diagnose, and treat TB, we will do well to remember the great public health icon, Paul Farmer, who tragically passed away earlier this year at a much too young age. Paul witnessed firsthand the devastating consequences of TB and its drug resistant forms in Haiti, Peru, and other parts of the world.

In addition to leading efforts to improve how TB is treated, Paul provided direct patient care in underserved communities and demanded that the world do more to meet their needs. As we honor Paul’s legacy, let us accelerate our efforts to find better tools to fight TB and other diseases of global health importance that exact a disproportionate toll among the poor and underserved.

References:

[1] Global tuberculosis report 2021. WHO. October 14, 2021.

[2] Prevention of tuberculosis in macaques after intravenous BCG immunization. Darrah PA, Zeppa JJ, Maiello P, Hackney JA, Wadsworth MH,. Hughes TK, Pokkali S, Swanson PA, Grant NL, Rodgers MA, Kamath M, Causgrove CM, Laddy DJ, Bonavia A, Casimiro D, Lin PL, Klein E, White AG, Scanga CA, Shalek AK, Roederer M, Flynn JL, and Seder RA. Nature. 2020 Jan 1; 577: 95–102.

[3] Prevention of M. tuberculosis Infection with H4:IC31 vaccine or BCG revaccination. Nemes E, Geldenhuys H, Rozot V, Rutkowski KT, Ratangee F,Bilek N., Mabwe S, Makhethe L, Erasmus M, Toefy A, Mulenga H, Hanekom WA, et al. N Engl J Med 2018; 379:138-149.

[4] Final analysis of a trial of M72/AS01E vaccine to prevent tuberculosis. Tait DR, Hatherill M, Van Der Meeren O, Ginsberg AM, Van Brakel E, Salaun B, Scriba TJ, Akite EJ, Ayles HM, et al.

[5] Pipeline Report 2021: Tuberculosis Vaccines. TAG. October 2021.

Links:

Tuberculosis (National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases/NIH)

NIAID Strategic Plan for Tuberculosis Research

Immune Mechanisms of Protection Against Mycobacterium tuberculosis Centers (IMPAc-TB) (NIAID)

Partners in Health (Boston, MA)

[Note: Acting NIH Director Lawrence Tabak has asked the heads of NIH’s Institutes and Centers (ICs) to contribute occasional guest posts to the blog to highlight some of the interesting science that they support and conduct. This is the seventh in the series of NIH IC guest posts that will run until a new permanent NIH director is in place.]

The Challenge of Tracking COVID-19’s Stealthy Spread

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

As our nation looks with hope toward controlling the coronavirus 2019 disease (COVID-19) pandemic, researchers are forging ahead with efforts to develop and implement strategies to prevent future outbreaks. It sounds straightforward. However, several new studies indicate that containing SARS-CoV-2—the novel coronavirus that causes COVID-19—will involve many complex challenges, not the least of which is figuring out ways to use testing technologies to our best advantage in the battle against this stealthy foe.

The first thing that testing may help us do is to identify those SARS-CoV-2-infected individuals who have no symptoms, but who are still capable of transmitting the virus. These individuals, along with their close contacts, will need to be quarantined rapidly to protect others. These kinds of tests detect viral material and generally analyze cells collected via nasal or throat swabs.

The second way we can use testing is to identify individuals who’ve already been infected with SARS-CoV-2, but who didn’t get seriously ill and can no longer transmit the virus to others. These individuals may now be protected against future infections, and, consequently, may be in a good position to care for people with COVID-19 or who are vulnerable to the infection. Such tests use blood samples to detect antibodies, which are blood proteins that our immune systems produce to attack viruses and other foreign invaders.

A new study, published in Nature Medicine [1], models what testing of asymptomatic individuals with active SARS-CoV-2 infections may mean for future containment efforts. To develop their model, researchers at China’s Guangzhou Medical University and the University of Hong Kong School of Public Health analyzed throat swabs collected from 94 people who were moderately ill and hospitalized with COVID-19. Frequent in-hospital swabbing provided an objective, chronological record—in some cases, for more than a month after a diagnosis—of each patient’s viral loads and infectiousness.

The model, which also factored in patients’ subjective recollections of when they felt poorly, indicates:

• On average, patients became infectious 2.3 days before onset of symptoms.

• Their highest level of potential viral spreading likely peaked hours before their symptoms appeared.

• Patients became rapidly less infectious within a week, although the virus likely remains in the body for some time.

The researchers then turned to data from a separate, previously published study [2], which documented the timing of 77 person-to-person transmissions of SARS-CoV-2. Comparing the two data sets, the researchers estimated that 44 percent of SARS-CoV-2 transmissions occur before people get sick.

Based on this two-part model, the researchers warned that traditional containment strategies (testing only of people with symptoms, contact tracing, quarantine) will face a stiff challenge keeping up with COVID-19. Indeed, they estimated that if more than 30 percent of new infections come from people who are asymptomatic, and they aren’t tested and found positive until 2 or 3 days later, public health officials will need to track down more than 90 percent of their close contacts and get them quarantined quickly to contain the virus.

The researchers also suggested alternate strategies for curbing SARS-CoV-2 transmission fueled by people who are initially asymptomatic. One possibility is digital tracing. It involves creating large networks of people who’ve agreed to install a special tracing app on their smart phones. If a phone user tests positive for COVID-19, everyone with the app who happened to have come in close contact with that person would be alerted anonymously and advised to shelter at home.

The NIH has a team that’s exploring various ways to carry out digital tracing while still protecting personal privacy. The private sector also has been exploring technological solutions, with Apple and Google recently announcing a partnership to develop application programming interfaces (APIs) to allow voluntary digital tracing for COVID-19 [3], The rollout of their first API is expected in May.

Of course, all these approaches depend upon widespread access to point-of-care testing that can give rapid results. The NIH is developing an ambitious program to accelerate the development of such testing technologies; stay tuned for more information about this in a forthcoming blog.

The second crucial piece of the containment puzzle is identifying those individuals who’ve already been infected by SARS-CoV-2, many unknowingly, but who are no longer infectious. Early results from an ongoing study on residents in Los Angeles County indicated that approximately 4.1 percent tested positive for antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 [4]. That figure is much higher than expected based on the county’s number of known COVID-19 cases, but jibes with preliminary findings from a different research group that conducted antibody testing on residents of Santa Clara County, CA [5].

Still, it’s important to keep in mind that SARS-CoV-2 antibody tests are just in the development stage. It’s possible some of these results might represent false positives—perhaps caused by antibodies to some other less serious coronavirus that’s been in the human population for a while.

More work needs to be done to sort this out. In fact, the NIH’s National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), which is our lead institute for infectious disease research, recently launched a study to help gauge how many adults in the U. S. with no confirmed history of a SARS-CoV-2 infection have antibodies to the virus. In this investigation, researchers will collect and analyze blood samples from as many as 10,000 volunteers to get a better picture of SARS-CoV-2’s prevalence and potential to spread within our country.

There’s still an enormous amount to learn about this major public health threat. In fact, NIAID just released its strategic plan for COVID-19 to outline its research priorities. The plan provides more information about the challenges of tracking SARS-CoV-2, as well as about efforts to accelerate research into possible treatments and vaccines. Take a look!

References:

[1] Temporal dynamics in viral shedding and transmissibility of COVID-19. He X, Lau EHY, Wu P, Deng X, Wang J, Hao X, Lau YC, Wong JY, Guan Y, Tan X, Mo X, Chen Y, Liao B, Chen W, Hu F, Zhang Q, Zhong M, Wu Y, Zhao L, Zhang F, Cowling BJ, Li F, Leung GM. Nat Med. 2020 Apr 15. [Epub ahead of publication]

[2] Early transmission dynamics in Wuhan, China, of novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia. Li, Q. et al. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020 Mar 26;382, 1199–1207.

[3] Apple and Google partner on COVID-19 contact tracing technology. Apple news release, April 10, 2020.

[4] USC-LA County Study: Early Results of Antibody Testing Suggest Number of COVID-19 Infections Far Exceeds Number of Confirmed Cases in Los Angeles County. County of Los Angeles Public Health News Release, April 20, 2020.

[5] COVID-19 Antibody Seroprevalence in Santa Clara County, California. Bendavid E, Mulaney B, Sood N, Sjah S, Ling E, Bromley-Dulfano R, Lai C, Saavedra-Walker R, Tedrow J, Tversky D, Bogan A, Kupiec T, Eichner D, Gupta R, Ioannidis JP, Bhattacharya J. medRxiv, Preprint posted on April 14, 2020.

Links:

Coronavirus (COVID-19) (NIH)

COVID-19, MERS & SARS (NIAID)

NIAID Strategic Plan for COVID-19 Research, FY 2020-2024

NIH Support: National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases

Can Smart Phone Apps Help Beat Pandemics?

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

In recent weeks, most of us have spent a lot of time learning about coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and thinking about what’s needed to defeat this and future pandemic threats. When the time comes for people to come out of their home seclusion, how will we avoid a second wave of infections? One thing that’s crucial is developing better ways to trace the recent contacts of individuals who’ve tested positive for the disease-causing agent—in this case, a highly infectious novel coronavirus.

Traditional contact tracing involves a team of public health workers who talk to people via the phone or in face-to-face meetings. This time-consuming, methodical process is usually measured in days, and can even stretch to weeks in complex situations with multiple contacts. But researchers are now proposing to take advantage of digital technology to try to get contact tracing done much faster, perhaps in just a few hours.

Most smart phones are equipped with wireless Bluetooth technology that creates a log of all opt-in mobile apps operating nearby—including opt-in apps on the phones of nearby people. This has prompted a number of research teams to explore the idea of creating an app to notify individuals of exposure risk. Specifically, if a smart phone user tests positive today for COVID-19, everyone on their recent Bluetooth log would be alerted anonymously and advised to shelter at home. In fact, in a recent paper in the journal Science, a British research group has gone so far to suggest that such digital tracing may be valuable in the months ahead to improve our chances of keeping COVID-19 under control [1].

The British team, led by Luca Ferretti, Christophe Fraser, and David Bonsall, Oxford University, started their analyses using previously published data on COVID-19 outbreaks in China, Singapore, and aboard the Diamond Princess cruise ship. With a focus on prevention, the researchers compared the different routes of transmission, including from people with and without symptoms of the infection.

Based on that data, they concluded that traditional contact tracing was too slow to keep pace with the rapidly spreading COVID-19 outbreaks. During the three outbreaks studied, people infected with the novel coronavirus had a median incubation period of about five days before they showed any symptoms of COVID-19. Researchers estimated that anywhere from one-third to one-half of all transmissions came from asymptomatic people during this incubation period. Moreover, assuming that symptoms ultimately arose and an infected person was then tested and received a COVID-19 diagnosis, public health workers would need at least several more days to perform the contact tracing by traditional means. By then, they would have little chance of getting ahead of the outbreak by isolating the infected person’s contacts to slow its rate of transmission.

When they examined the situation in China, the researchers found that available data show a correlation between the roll-out of smart phone contact-tracing apps and the emergence of what appears to be sustained suppression of COVID-19 infection. Their analyses showed that the same held true in South Korea, where data collected through a smart phone app was used to recommend quarantine.

Despite its potential benefits in controlling or even averting pandemics, the British researchers acknowledged that digital tracing poses some major ethical, legal, and social issues. In China, people were required to install the digital tracing app on their phones if they wanted to venture outside their immediate neighborhoods. The app also displayed a color-coded warning system to enforce or relax restrictions on a person’s movements around a city or province. The Chinese app also relayed to a central database the information that it had gathered on phone users’ movements and COVID-19 status, raising serious concerns about data security and privacy of personal information.

In their new paper, the Oxford team, which included a bioethicist, makes the case for increased social dialogue about how best to employ digital tracing in ways the benefit human health. This is a far-reaching discussion with implications far beyond times of pandemic. Although the team analyzed digital tracing data for COVID-19, the algorithms that drive these apps could be adapted to track the spread of other common infectious diseases, such as seasonal influenza.

The study’s authors also raised another vital point. Even the most-sophisticated digital tracing app won’t be of much help if smart phone users don’t download it. Without widespread installation, the apps are unable to gather enough data to enable effective digital tracing. Indeed, the researchers estimate that about 60 percent of new COVID-19 cases in a community would need to be detected–and roughly the same percentage of contacts traced—to squelch the spread of the deadly virus.

Such numbers have app designers working hard to discover the right balance between protecting public health and ensuring personal rights. That includes NIH grantee Trevor Bedford, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle. He and his colleagues just launched NextTrace, a project that aims to build an opt-in app community for “digital participatory contact tracing” of COVID-19. Here at NIH, we have a team that is actively exploring the kind of technology that could achieve the benefits without unduly compromising personal privacy.

Bedford emphasizes that he and his colleagues aren’t trying to duplicate efforts already underway. Rather, they want to collaborate with others help to build a scientifically and ethically sound foundation for digital tracing aimed at improving the health of all humankind.

Reference:

[1] Quantifying SARS-CoV-2 transmission suggests epidemic control with digital contact tracing. Ferretti L, Wymant C, Kendall M, Zhao L, Nurtay A, Abeler-Dörner L, Parker M, Bonsall D, Fraser C. Science. 2020 Mar 31. [Epub ahead of print]

Links:

Coronavirus (COVID-19) (NIH)

COVID-19, MERS & SARS (National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases/NIH)

NextTrace (Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle)

Bedford Lab (Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center)

NIH Support: National Institute of General Medical Sciences

Structural Biology Points Way to Coronavirus Vaccine

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Credit: McLellan Lab, University of Texas at Austin

The recent COVID-19 outbreak of a novel type of coronavirus that began in China has prompted a massive global effort to contain and slow its spread. Despite those efforts, over the last month the virus has begun circulating outside of China in multiple countries and territories.

Cases have now appeared in the United States involving some affected individuals who haven’t traveled recently outside the country. They also have had no known contact with others who have recently arrived from China or other countries where the virus is spreading. The NIH and other U.S. public health agencies stand on high alert and have mobilized needed resources to help not only in its containment, but in the development of life-saving interventions.

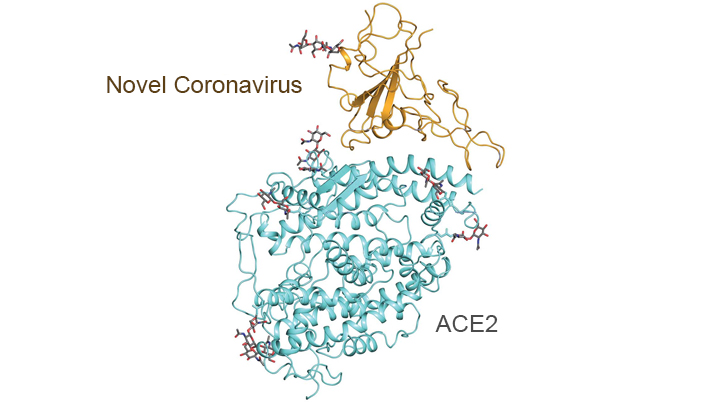

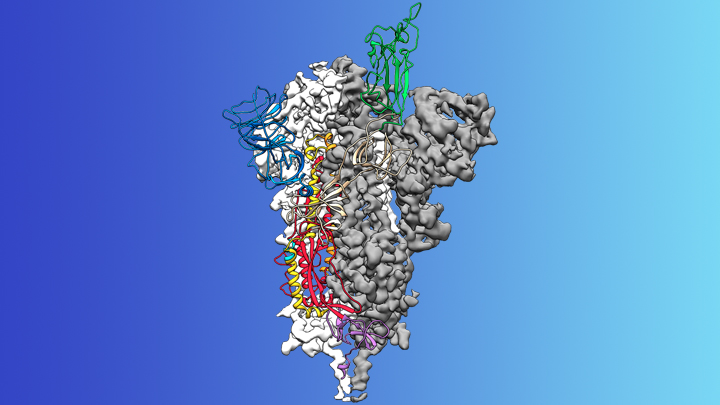

On the treatment and prevention front, some encouraging news was recently reported. In record time, an NIH-funded team of researchers has created the first atomic-scale map of a promising protein target for vaccine development [1]. This is the so-called spike protein on the new coronavirus that causes COVID-19. As shown above, a portion of this spiky surface appendage (green) allows the virus to bind a receptor on human cells, causing other portions of the spike to fuse the viral and human cell membranes. This process is needed for the virus to gain entry into cells and infect them.

Preclinical studies in mice of a candidate vaccine based on this spike protein are already underway at NIH’s Vaccine Research Center (VRC), part of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID). An early-stage phase I clinical trial of this vaccine in people is expected to begin within weeks. But there will be many more steps after that to test safety and efficacy, and then to scale up to produce millions of doses. Even though this timetable will potentially break all previous speed records, a safe and effective vaccine will take at least another year to be ready for widespread deployment.

Coronaviruses are a large family of viruses, including some that cause “the common cold” in healthy humans. In fact, these viruses are found throughout the world and account for up to 30 percent of upper respiratory tract infections in adults.

This outbreak of COVID-19 marks the third time in recent years that a coronavirus has emerged to cause severe disease and death in some people. Earlier coronavirus outbreaks included SARS (severe acute respiratory syndrome), which emerged in late 2002 and disappeared two years later, and MERS (Middle East respiratory syndrome), which emerged in 2012 and continues to affect people in small numbers.

Soon after COVID-19 emerged, the new coronavirus, which is closely related to SARS, was recognized as its cause. NIH-funded researchers including Jason McLellan, an alumnus of the VRC and now at The University of Texas at Austin, were ready. They’d been studying coronaviruses in collaboration with NIAID investigators for years, with special attention to the spike proteins.

Just two weeks after Chinese scientists reported the first genome sequence of the virus [2], McLellan and his colleagues designed and produced samples of its spike protein. Importantly, his team had earlier developed a method to lock coronavirus spike proteins into a shape that makes them both easier to analyze structurally via the high-resolution imaging tool cryo-electron microscopy and to use in vaccine development efforts.

After locking the spike protein in the shape it takes before fusing with a human cell to infect it, the researchers reconstructed its atomic-scale 3D structural map in just 12 days. Their results, published in Science, confirm that the spike protein on the virus that causes COVID-19 is quite similar to that of its close relative, the SARS virus. It also appears to bind human cells more tightly than the SARS virus, which may help to explain why the new coronavirus appears to spread more easily from person to person, mainly by respiratory transmission.

McLellan’s team and his NIAID VRC counterparts also plan to use the stabilized spike protein as a probe to isolate naturally produced antibodies from people who’ve recovered from COVID-19. Such antibodies might form the basis of a treatment for people who’ve been exposed to the virus, such as health care workers.

The NIAID is now working with the biotechnology company Moderna, Cambridge, MA, to use the latest findings to develop a vaccine candidate using messenger RNA (mRNA), molecules that serve as templates for making proteins. The goal is to direct the body to produce a spike protein in such a way to elicit an immune response and the production of antibodies. An early clinical trial of the vaccine in people is expected to begin in the coming weeks. Other vaccine candidates are also in preclinical development.

Meanwhile, the first clinical trial in the U.S. to evaluate an experimental treatment for COVID-19 is already underway at the University of Nebraska Medical Center’s biocontainment unit [3]. The NIH-sponsored trial will evaluate the safety and efficacy of the experimental antiviral drug remdesivir in hospitalized adults diagnosed with COVID-19. The first participant is an American who was repatriated after being quarantined on the Diamond Princess cruise ship in Japan.

As noted, the risk of contracting COVID-19 in the United States is currently low, but the situation is changing rapidly. One of the features that makes the virus so challenging to stay in front of is its long latency period before the characteristic flu-like fever, cough, and shortness of breath manifest. In fact, people infected with the virus may not show any symptoms for up to two weeks, allowing them to pass it on to others in the meantime. You can track the reported cases in the United States on the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s website.

As the outbreak continues over the coming weeks and months, you can be certain that NIH and other U.S. public health organizations are working at full speed to understand this virus and to develop better diagnostics, treatments, and vaccines.

References:

[1] Cryo-EM structure of the 2019-nCoV spike in the prefusion conformation. Wrapp D, Wang N, Corbett KS, Goldsmith JA, Hsieh CL, Abiona O, Graham BS, McLellan JS. Science. 2020 Feb 19.

[2] A new coronavirus associated with human respiratory disease in China. Wu F, Zhao S, Yu B, Chen YM, Wang W, Song ZG, Hu Y, Tao ZW, Tian JH, Pei YY, Yuan ML, Zhang YL, Dai FH, Liu Y, Wang QM, Zheng JJ, Xu L, Holmes EC, Zhang YZ. Nature. 2020 Feb 3.

[3] NIH clinical trial of remdesivir to treat COVID-19 begins. NIH News Release. Feb 25, 2020.

Links:

Coronaviruses (National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases/NIH)

Coronavirus (COVID-19) (NIAID)

Coronavirus Disease 2019 (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta)

NIH Support: National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases

Celebrating 2019 Biomedical Breakthroughs

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Happy New Year! As we say goodbye to the Teens, let’s take a look back at 2019 and some of the groundbreaking scientific discoveries that closed out this remarkable decade.

Each December, the reporters and editors at the journal Science select their breakthrough of the year, and the choice for 2019 is nothing less than spectacular: An international network of radio astronomers published the first image of a black hole, the long-theorized cosmic singularity where gravity is so strong that even light cannot escape [1]. This one resides in a galaxy 53 million light-years from Earth! (A light-year equals about 6 trillion miles.)

Though the competition was certainly stiff in 2019, the biomedical sciences were well represented among Science’s “runner-up” breakthroughs. They include three breakthroughs that have received NIH support. Let’s take a look at them:

In a first, drug treats most cases of cystic fibrosis: Last October, two international research teams reported the results from phase 3 clinical trials of the triple drug therapy Trikafta to treat cystic fibrosis (CF). Their data showed Trikafta effectively compensates for the effects of a mutation carried by about 90 percent of people born with CF. Upon reviewing these impressive data, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved Trikafta, developed by Vertex Pharmaceuticals.

The approval of Trikafta was a wonderful day for me personally, having co-led the team that isolated the CF gene 30 years ago. A few years later, I wrote a song called “Dare to Dream” imagining that wonderful day when “the story of CF is history.” Though we’ve still got more work to do, we’re getting a lot closer to making that dream come true. Indeed, with the approval of Trikafta, most people with CF have for the first time ever a real chance at managing this genetic disease as a chronic condition over the course of their lives. That’s a tremendous accomplishment considering that few with CF lived beyond their teens as recently as the 1980s.

Such progress has been made possible by decades of work involving a vast number of researchers, many funded by NIH, as well as by more than two decades of visionary and collaborative efforts between the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation and Aurora Biosciences (now, Vertex) that built upon that fundamental knowledge of the responsible gene and its protein product. Not only did this innovative approach serve to accelerate the development of therapies for CF, it established a model that may inform efforts to develop therapies for other rare genetic diseases.

Hope for Ebola patients, at last: It was just six years ago that news of a major Ebola outbreak in West Africa sounded a global health emergency of the highest order. Ebola virus disease was then recognized as an untreatable, rapidly fatal illness for the majority of those who contracted it. Though international control efforts ultimately contained the spread of the virus in West Africa within about two years, over 28,600 cases had been confirmed leading to more than 11,000 deaths—marking the largest known Ebola outbreak in human history. Most recently, another major outbreak continues to wreak havoc in northeastern Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), where violent civil unrest is greatly challenging public health control efforts.

As troubling as this news remains, 2019 brought a needed breakthrough for the millions of people living in areas susceptible to Ebola outbreaks. A randomized clinical trial in the DRC evaluated four different drugs for treating acutely infected individuals, including an antibody against the virus called mAb114, and a cocktail of anti-Ebola antibodies referred to as REGN-EB3. The trial’s preliminary data showed that about 70 percent of the patients who received either mAb114 or the REGN-EB3 antibody cocktail survived, compared with about half of those given either of the other two medicines.

So compelling were these preliminary results that the trial, co-sponsored by NIH’s National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) and the DRC’s National Institute for Biomedical Research, was halted last August. The results were also promptly made public to help save lives and stem the latest outbreak. All Ebola patients in the DRC treatment centers now are treated with one or the other of these two options. The trial results were recently published.

The NIH-developed mAb114 antibody and the REGN-EB3 cocktail are the first therapeutics to be shown in a scientifically rigorous study to be effective at treating Ebola. This work also demonstrates that ethically sound clinical research can be conducted under difficult conditions in the midst of a disease outbreak. In fact, the halted study was named Pamoja Tulinde Maisha (PALM), which means “together save lives” in Kiswahili.

To top off the life-saving progress in 2019, the FDA just approved the first vaccine for Ebola. Called Ervebo (earlier rVSV-ZEBOV), this single-dose injectable vaccine is a non-infectious version of an animal virus that has been genetically engineered to carry a segment of a gene from the Zaire species of the Ebola virus—the virus responsible for the current DRC outbreak and the West Africa outbreak. Because the vaccine does not contain the whole Zaire virus, it can’t cause Ebola. Results from a large study in Guinea conducted by the WHO indicated that the vaccine offered substantial protection against Ebola virus disease. Ervebo, produced by Merck, has already been given to over 259,000 individuals as part of the response to the DRC outbreak. The NIH has supported numerous clinical trials of the vaccine, including an ongoing study in West Africa.

Microbes combat malnourishment: Researchers discovered a few years ago that abnormal microbial communities, or microbiomes, in the intestine appear to contribute to childhood malnutrition. An NIH-supported research team followed up on this lead with a study of kids in Bangladesh, and it published last July its groundbreaking finding: that foods formulated to repair the “gut microbiome” helped malnourished kids rebuild their health. The researchers were able to identify a network of 15 bacterial species that consistently interact in the gut microbiomes of Bangladeshi children. In this month-long study, this bacterial network helped the researchers characterize a child’s microbiome and/or its relative state of repair.

But a month isn’t long enough to determine how the new foods would help children grow and recover. The researchers are conducting a similar study that is much longer and larger. Globally, malnutrition affects an estimated 238 million children under the age 5, stunting their normal growth, compromising their health, and limiting their mental development. The hope is that these new foods and others adapted for use around the world soon will help many more kids grow up to be healthy adults.

Measles Resurgent: The staff at Science also listed their less-encouraging 2019 Breakdowns of the Year, and unfortunately the biomedical sciences made the cut with the return of measles in the U.S. Prior to 1963, when the measles vaccine was developed, 3 to 4 million Americans were sickened by measles each year. Each year about 500 children would die from measles, and many more would suffer lifelong complications. As more people were vaccinated, the incidence of measles plummeted. By the year 2000, the disease was even declared eliminated from the U.S.

But, as more parents have chosen not to vaccinate their children, driven by the now debunked claim that vaccines are connected to autism, measles has made a very preventable comeback. Last October, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported an estimated 1,250 measles cases in the United States at that point in 2019, surpassing the total number of cases reported annually in each of the past 25 years.

The good news is those numbers can be reduced if more people get the vaccine, which has been shown repeatedly in many large and rigorous studies to be safe and effective. The CDC recommends that children should receive their first dose by 12 to 15 months of age and a second dose between the ages of 4 and 6. Older people who’ve been vaccinated or have had the measles previously should consider being re-vaccinated, especially if they live in places with low vaccination rates or will be traveling to countries where measles are endemic.

Despite this public health breakdown, 2019 closed out a memorable decade of scientific discovery. The Twenties will build on discoveries made during the Teens and bring us even closer to an era of precision medicine to improve the lives of millions of Americans. So, onward to 2020—and happy New Year!

Reference:

[1] 2019 Breakthrough of the Year. Science, December 19, 2019.

NIH Support: These breakthroughs represent the culmination of years of research involving many investigators and the support of multiple NIH institutes.

Next Page