HIV

Immune Resilience is Key to a Long and Healthy Life

Posted on by Lawrence Tabak, D.D.S., Ph.D.

Do you feel as if you or perhaps your family members are constantly coming down with illnesses that drag on longer than they should? Or, maybe you’re one of those lucky people who rarely becomes ill and, if you do, recovers faster than others.

It’s clear that some people generally are more susceptible to infectious illnesses, while others manage to stay healthier or bounce back more quickly, sometimes even into old age. Why is this? A new study from an NIH-supported team has an intriguing answer [1]. The difference, they suggest, may be explained in part by a new measure of immunity they call immune resilience—the ability of the immune system to rapidly launch attacks that defend effectively against infectious invaders and respond appropriately to other types of inflammatory stressors, including aging or other health conditions, and then quickly recover, while keeping potentially damaging inflammation under wraps.

The findings in the journal Nature Communications come from an international team led by Sunil Ahuja, University of Texas Health Science Center and the Department of Veterans Affairs Center for Personalized Medicine, both in San Antonio. To understand the role of immune resilience and its effect on longevity and health outcomes, the researchers looked at multiple other studies including healthy individuals and those with a range of health conditions that challenged their immune systems.

By looking at multiple studies in varied infectious and other contexts, they hoped to find clues as to why some people remain healthier even in the face of varied inflammatory stressors, ranging from mild to more severe. But to understand how immune resilience influences health outcomes, they first needed a way to measure or grade this immune attribute.

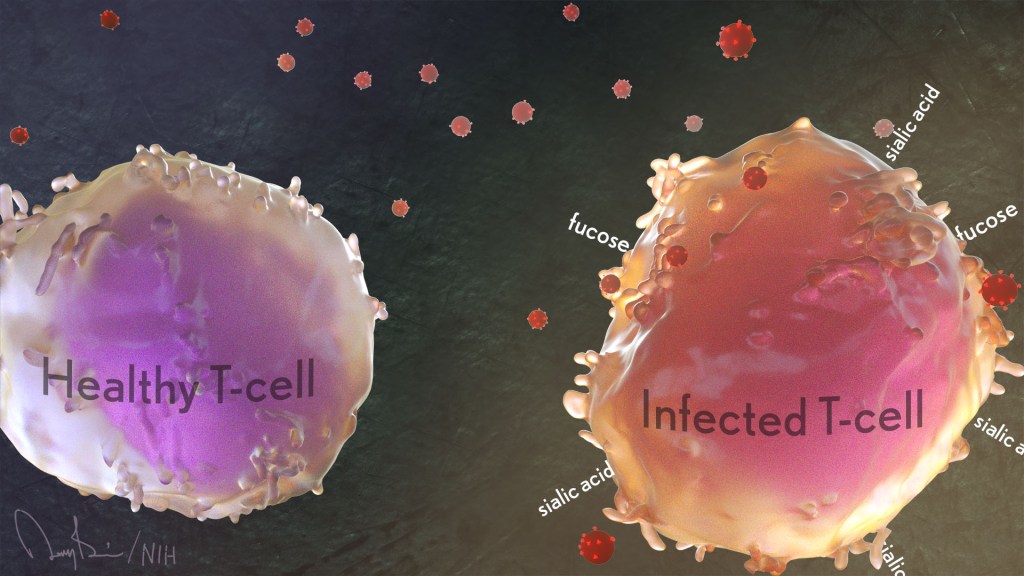

The researchers developed two methods for measuring immune resilience. The first metric, a laboratory test called immune health grades (IHGs), is a four-tier grading system that calculates the balance between infection-fighting CD8+ and CD4+ T-cells. IHG-I denotes the best balance tracking the highest level of resilience, and IHG-IV denotes the worst balance tracking the lowest level of immune resilience. An imbalance between the levels of these T cell types is observed in many people as they age, when they get sick, and in people with autoimmune diseases and other conditions.

The researchers also developed a second metric that looks for two patterns of expression of a select set of genes. One pattern associated with survival and the other with death. The survival-associated pattern is primarily related to immune competence, or the immune system’s ability to function swiftly and restore activities that encourage disease resistance. The mortality-associated genes are closely related to inflammation, a process through which the immune system eliminates pathogens and begins the healing process but that also underlies many disease states.

Their studies have shown that high expression of the survival-associated genes and lower expression of mortality-associated genes indicate optimal immune resilience, correlating with a longer lifespan. The opposite pattern indicates poor resilience and a greater risk of premature death. When both sets of genes are either low or high at the same time, immune resilience and mortality risks are more moderate.

In the newly reported study initiated in 2014, Ahuja and his colleagues set out to assess immune resilience in a collection of about 48,500 people, with or without various acute, repetitive, or chronic challenges to their immune systems. In an earlier study, the researchers showed that this novel way to measure immune status and resilience predicted hospitalization and mortality during acute COVID-19 across a wide age spectrum [2].

The investigators have analyzed stored blood samples and publicly available data representing people, many of whom were healthy volunteers, who had enrolled in different studies conducted in Africa, Europe, and North America. Volunteers ranged in age from 9 to 103 years. They also evaluated participants in the Framingham Heart Study, a long-term effort to identify common factors and characteristics that contribute to cardiovascular disease.

To examine people with a wide range of health challenges and associated stresses on their immune systems, the team also included participants who had influenza or COVID-19, and people living with HIV. They also included kidney transplant recipients, people with lifestyle factors that put them at high risk for sexually transmitted infections, and people who’d had sepsis, a condition in which the body has an extreme and life-threatening response following an infection.

The question in all these contexts was the same: How well did the two metrics of immune resilience predict an individual’s health outcomes and lifespan? The short answer is that immune resilience, longevity, and better health outcomes tracked together well. Those with metrics indicating optimal immune resilience generally had better health outcomes and lived longer than those who had lower scores on the immunity grading scale. Indeed, those with optimal immune resilience were more likely to:

- Live longer,

- Resist HIV infection or the progression from HIV to AIDS,

- Resist symptomatic influenza,

- Resist a recurrence of skin cancer after a kidney transplant,

- Survive COVID-19, and

- Survive sepsis.

The study also revealed other interesting findings. While immune resilience generally declines with age, some people maintain higher levels of immune resilience as they get older for reasons that aren’t yet known, according to the researchers. Some people also maintain higher levels of immune resilience despite the presence of inflammatory stress to their immune systems such as during HIV infection or acute COVID-19. People of all ages can show high or low immune resilience. The study also found that higher immune resilience is more common in females than it is in males.

The findings suggest that there is a lot more to learn about why people differ in their ability to preserve optimal immune resilience. With further research, it may be possible to develop treatments or other methods to encourage or restore immune resilience as a way of improving general health, according to the study team.

The researchers suggest it’s possible that one day checkups of a person’s immune resilience could help us to understand and predict an individual’s health status and risk for a wide range of health conditions. It could also help to identify those individuals who may be at a higher risk of poor outcomes when they do get sick and may need more aggressive treatment. Researchers may also consider immune resilience when designing vaccine clinical trials.

A more thorough understanding of immune resilience and discovery of ways to improve it may help to address important health disparities linked to differences in race, ethnicity, geography, and other factors. We know that healthy eating, exercising, and taking precautions to avoid getting sick foster good health and longevity; in the future, perhaps we’ll also consider how our immune resilience measures up and take steps to achieve or maintain a healthier, more balanced, immunity status.

References:

[1] Immune resilience despite inflammatory stress promotes longevity and favorable health outcomes including resistance to infection. Ahuja SK, Manoharan MS, Lee GC, McKinnon LR, Meunier JA, Steri M, Harper N, Fiorillo E, Smith AM, Restrepo MI, Branum AP, Bottomley MJ, Orrù V, Jimenez F, Carrillo A, Pandranki L, Winter CA, Winter LA, Gaitan AA, Moreira AG, Walter EA, Silvestri G, King CL, Zheng YT, Zheng HY, Kimani J, Blake Ball T, Plummer FA, Fowke KR, Harden PN, Wood KJ, Ferris MT, Lund JM, Heise MT, Garrett N, Canady KR, Abdool Karim SS, Little SJ, Gianella S, Smith DM, Letendre S, Richman DD, Cucca F, Trinh H, Sanchez-Reilly S, Hecht JM, Cadena Zuluaga JA, Anzueto A, Pugh JA; South Texas Veterans Health Care System COVID-19 team; Agan BK, Root-Bernstein R, Clark RA, Okulicz JF, He W. Nat Commun. 2023 Jun 13;14(1):3286. doi: 10.1038/s41467-023-38238-6. PMID: 37311745.

[2] Immunologic resilience and COVID-19 survival advantage. Lee GC, Restrepo MI, Harper N, Manoharan MS, Smith AM, Meunier JA, Sanchez-Reilly S, Ehsan A, Branum AP, Winter C, Winter L, Jimenez F, Pandranki L, Carrillo A, Perez GL, Anzueto A, Trinh H, Lee M, Hecht JM, Martinez-Vargas C, Sehgal RT, Cadena J, Walter EA, Oakman K, Benavides R, Pugh JA; South Texas Veterans Health Care System COVID-19 Team; Letendre S, Steri M, Orrù V, Fiorillo E, Cucca F, Moreira AG, Zhang N, Leadbetter E, Agan BK, Richman DD, He W, Clark RA, Okulicz JF, Ahuja SK. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2021 Nov;148(5):1176-1191. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2021.08.021. Epub 2021 Sep 8. PMID: 34508765; PMCID: PMC8425719.

Links:

COVID-19 Research (NIH)

HIV Info (NIH)

Sepsis (National Institute of General Medical Sciences/NIH)

Sunil Ahuja (University of Texas Health Science Center, San Antonio)

Framingham Heart Study (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute/NIH)

“A Secret to Health and Long Life? Immune Resilience, NIAID Grantees Report,” NIAID Now Blog, June 13, 2023

NIH Support: National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases; National Institute on Aging; National Institute of Mental Health; National Institute of General Medical Sciences; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute

Encouraging First-in-Human Results for a Promising HIV Vaccine

Posted on by Lawrence Tabak, D.D.S., Ph.D.

In recent years, we’ve witnessed some truly inspiring progress in vaccine development. That includes the mRNA vaccines that were so critical during the COVID-19 pandemic, the first approved vaccine for respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), and a “universal flu vaccine” candidate that could one day help to thwart future outbreaks of more novel influenza viruses.

Inspiring progress also continues to be made toward a safe and effective vaccine for HIV, which still infects about 1.5 million people around the world each year [1]. A prime example is the recent first-in-human trial of an HIV vaccine made in the lab from a unique protein nanoparticle, a molecular construct measuring just a few billionths of a meter.

The results of this early phase clinical study, published recently in the journal Science Translational Medicine [2] and earlier in Science [3], showed that the experimental HIV nanoparticle vaccine is safe in people. While this vaccine alone will not offer HIV protection and is intended to be part of an eventual broader, multistep vaccination regimen, the researchers also determined that it elicited a robust immune response in nearly all 36 healthy adult volunteers.

How robust? The results show that the nanoparticle vaccine, known by the lab name eOD-GT8 60-mer, successfully expanded production of a rare type of antibody-producing immune B cell in nearly all recipients.

What makes this rare type of B cell so critical is that it is the cellular precursor of other B cells capable of producing broadly neutralizing antibodies (bnAbs) to protect against diverse HIV variants. Also very good news, the vaccine elicited broad responses from helper T cells. They play a critical supportive role for those essential B cells and their development of the needed broadly neutralizing antibodies.

For decades, researchers have brought a wealth of ideas to bear on developing a safe and effective HIV vaccine. However, crossing the finish line—an FDA-approved vaccine—has proved profoundly difficult.

A major reason is the human immune system is ill equipped to recognize HIV and produce the needed infection-fighting antibodies. And yet the medical literature includes reports of people with HIV who have produced the needed antibodies, showing that our immune system can do it.

But these people remain relatively rare, and the needed robust immunity clocks in only after many years of infection. On top of that, HIV has a habit of mutating rapidly to produce a wide range of identity-altering variants. For a vaccine to work, it most likely will need to induce the production of bnAbs that recognize and defend against not one, but the many different faces of HIV.

To make the uncommon more common became the quest of a research team that includes scientists William Schief, Scripps Research and IAVI Neutralizing Antibody Center, La Jolla, CA; M. Juliana McElrath, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center, Seattle; and Kristen Cohen, a former member of the McElrath lab now at Moderna, Cambridge, MA. The team, with NIH collaborators and support, has been plotting out a stepwise approach to train the immune system into making the needed bnAbs that recognize many HIV variants.

The critical first step is to prime the immune system to make more of those coveted bnAb-precursor B cells. That’s where the protein nanoparticle known as eOD-GT8 60-mer enters the picture.

This nanoparticle, administered by injection, is designed to mimic a small, highly conserved segment of an HIV protein that allows the virus to bind and infect human cells. In the body, those nanoparticles launch an immune response and then quickly vanish. But because this important protein target for HIV vaccines is so tiny, its signal needed amplification for immune system detection.

To boost the signal, the researchers started with a bacterial protein called lumazine synthase (LumSyn). It forms the scaffold, or structural support, of the self-assembling nanoparticle. Then, they added to the LumSyn scaffold 60 copies of the key HIV protein. This louder HIV signal is tailored to draw out and engage those very specific B cells with the potential to produce bnAbs.

As the first-in-human study showed, the nanoparticle vaccine was safe when administered twice to each participant eight weeks apart. People reported only mild to moderate side effects that went away in a day or two. The vaccine also boosted production of the desired B cells in all but one vaccine recipient (35 of 36). The idea is that this increase in essential B cells sets the stage for the needed additional steps—booster shots that can further coax these cells along toward making HIV protective bnAbs.

The latest finding in Science Translational Medicine looked deeper into the response of helper T cells in the same trial volunteers. Again, the results appear very encouraging. The researchers observed CD4 T cells specific to the HIV protein and to the LumSyn in 84 percent and 93 percent of vaccine recipients. Their analyses also identified key hotspots that the T cells recognized, which is important information for refining future vaccines to elicit helper T cells.

The team reports that they’re now collaborating with Moderna, the developer of one of the two successful mRNA-based COVID-19 vaccines, on an mRNA version of eOD-GT8 60-mer. That’s exciting because mRNA vaccines are much faster and easier to produce and modify, which should now help to move this line of research along at a faster clip.

Indeed, two International AIDS Vaccine Initiative (IAVI)-sponsored clinical trials of the mRNA version are already underway, one in the U.S. and the other in Rwanda and South Africa [4]. It looks like this team and others are now on a promising track toward following the basic science and developing a multistep HIV vaccination regimen that guides the immune response and its stepwise phases in the right directions.

As we look back on more than 40 years of HIV research, it’s heartening to witness the progress that continues toward ending the HIV epidemic. This includes the recent FDA approval of the drug Apretude, the first injectable treatment option for pre-exposure prevention of HIV, and the continued global commitment to produce a safe and effective vaccine.

References:

[1] Global HIV & AIDS statistics fact sheet. UNAIDS.

[2] A first-in-human germline-targeting HIV nanoparticle vaccine induced broad and publicly targeted helper T cell responses. Cohen KW, De Rosa SC, Fulp WJ, deCamp AC, Fiore-Gartland A, Laufer DS, Koup RA, McDermott AB, Schief WR, McElrath MJ. Sci Transl Med. 2023 May 24;15(697):eadf3309.

[3] Vaccination induces HIV broadly neutralizing antibody precursors in humans. Leggat DJ, Cohen KW, Willis JR, Fulp WJ, deCamp AC, Koup RA, Laufer DS, McElrath MJ, McDermott AB, Schief WR. Science. 2022 Dec 2;378(6623):eadd6502.

[4] IAVI and Moderna launch first-in-Africa clinical trial of mRNA HIV vaccine development program. IAVI. May 18, 2022.

Links:

Progress Toward an Eventual HIV Vaccine, NIH Research Matters, Dec. 13, 2022.

NIH Statement on HIV Vaccine Awareness Day 2023, Auchincloss H, Kapogiannis, B. May, 18, 2023.

HIV Vaccine Development (National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases/NIH)

International AIDS Vaccine Initiative (IAVI) (New York, NY)

William Schief (Scripps Research, La Jolla, CA)

Julie McElrath (Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center, Seattle, WA)

McElrath Lab (Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center, Seattle, WA)

NIH Support: National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases

Thank You, Dr. Fauci

Posted on by Lawrence Tabak, D.D.S., Ph.D.

What A Year It Was for Science Advances!

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

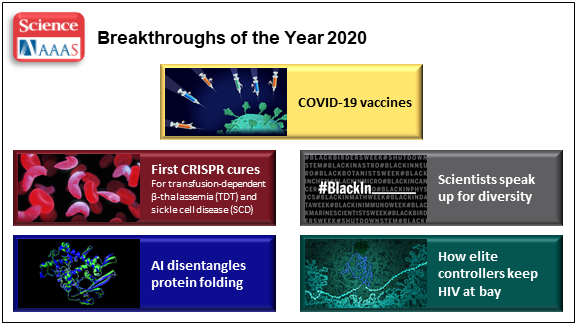

At the close of every year, editors and writers at the journal Science review the progress that’s been made in all fields of science—from anthropology to zoology—to select the biggest advance of the past 12 months. In most cases, this Breakthrough of the Year is as tough to predict as the Oscar for Best Picture. Not in 2020. In a year filled with a multitude of challenges posed by the emergence of the deadly coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-2019), the breakthrough was the development of the first vaccines to protect against this pandemic that’s already claimed the lives of more than 360,000 Americans.

In keeping with its annual tradition, Science also selected nine runner-up breakthroughs. This impressive list includes at least three areas that involved efforts supported by NIH: therapeutic applications of gene editing, basic research understanding HIV, and scientists speaking up for diversity. Here’s a quick rundown of all the pioneering advances in biomedical research, both NIH and non-NIH funded:

Shots of Hope. A lot of things happened in 2020 that were unprecedented. At the top of the list was the rapid development of COVID-19 vaccines. Public and private researchers accomplished in 10 months what normally takes about 8 years to produce two vaccines for public use, with more on the way in 2021. In my more than 25 years at NIH, I’ve never encountered such a willingness among researchers to set aside their other concerns and gather around the same table to get the job done fast, safely, and efficiently for the world.

It’s also pretty amazing that the first two conditionally approved vaccines from Pfizer and Moderna were found to be more than 90 percent effective at protecting people from infection with SARS-CoV-2, the coronavirus that causes COVID-19. Both are innovative messenger RNA (mRNA) vaccines, a new approach to vaccination.

For this type of vaccine, the centerpiece is a small, non-infectious snippet of mRNA that encodes the instructions to make the spike protein that crowns the outer surface of SARS-CoV-2. When the mRNA is injected into a shoulder muscle, cells there will follow the encoded instructions and temporarily make copies of this signature viral protein. As the immune system detects these copies, it spurs the production of antibodies and helps the body remember how to fend off SARS-CoV-2 should the real thing be encountered.

It also can’t be understated that both mRNA vaccines—one developed by Pfizer and the other by Moderna in conjunction with NIH’s National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases—were rigorously evaluated in clinical trials. Detailed data were posted online and discussed in all-day meetings of an FDA Advisory Committee, open to the public. In fact, given the high stakes, the level of review probably was more scientifically rigorous than ever.

First CRISPR Cures: One of the most promising areas of research now underway involves gene editing. These tools, still relatively new, hold the potential to fix gene misspellings—and potentially cure—a wide range of genetic diseases that were once to be out of reach. Much of the research focus has centered on CRISPR/Cas9. This highly precise gene-editing system relies on guide RNA molecules to direct a scissor-like Cas9 enzyme to just the right spot in the genome to cut out or correct a disease-causing misspelling.

In late 2020, a team of researchers in the United States and Europe succeeded for the first time in using CRISPR to treat 10 people with sickle cell disease and transfusion-dependent beta thalassemia. As published in the New England Journal of Medicine, several months after this non-heritable treatment, all patients no longer needed frequent blood transfusions and are living pain free [1].

The researchers tested a one-time treatment in which they removed bone marrow from each patient, modified the blood-forming hematopoietic stem cells outside the body using CRISPR, and then reinfused them into the body. To prepare for receiving the corrected cells, patients were given toxic bone marrow ablation therapy, in order to make room for the corrected cells. The result: the modified stem cells were reprogrammed to switch back to making ample amounts of a healthy form of hemoglobin that their bodies produced in the womb. While the treatment is still risky, complex, and prohibitively expensive, this work is an impressive start for more breakthroughs to come using gene editing technologies. NIH, including its Somatic Cell Genome Editing program, continues to push the technology to accelerate progress and make gene editing cures for many disorders simpler and less toxic.

Scientists Speak Up for Diversity: The year 2020 will be remembered not only for COVID-19, but also for the very public and inescapable evidence of the persistence of racial discrimination in the United States. Triggered by the killing of George Floyd and other similar events, Americans were forced to come to grips with the fact that our society does not provide equal opportunity and justice for all. And that applies to the scientific community as well.

Science thrives in safe, diverse, and inclusive research environments. It suffers when racism and bigotry find a home to stifle diversity—and community for all—in the sciences. For the nation’s leading science institutions, there is a place and a calling to encourage diversity in the scientific workplace and provide the resources to let it flourish to everyone’s benefit.

For those of us at NIH, last year’s peaceful protests and hashtags were noticed and taken to heart. That’s one of the many reasons why we will continue to strengthen our commitment to building a culturally diverse, inclusive workplace. For example, we have established the NIH Equity Committee. It allows for the systematic tracking and evaluation of diversity and inclusion metrics for the intramural research program for each NIH institute and center. There is also the recently founded Distinguished Scholars Program, which aims to increase the diversity of tenure track investigators at NIH. Recently, NIH also announced that it will provide support to institutions to recruit diverse groups or “cohorts” of early-stage research faculty and prepare them to thrive as NIH-funded researchers.

AI Disentangles Protein Folding: Proteins, which are the workhorses of the cell, are made up of long, interconnected strings of amino acids that fold into a wide variety of 3D shapes. Understanding the precise shape of a protein facilitates efforts to figure out its function, its potential role in a disease, and even how to target it with therapies. To gain such understanding, researchers often try to predict a protein’s precise 3D chemical structure using basic principles of physics—including quantum mechanics. But while nature does this in real time zillions of times a day, computational approaches have not been able to do this—until now.

Of the roughly 170,000 proteins mapped so far, most have had their structures deciphered using powerful imaging techniques such as x-ray crystallography and cryo–electron microscopy (cryo-EM). But researchers estimate that there are at least 200 million proteins in nature, and, as amazing as these imaging techniques are, they are laborious, and it can take many months or years to solve 3D structure of a single protein. So, a breakthrough certainly was needed!

In 2020, researchers with the company Deep Mind, London, developed an artificial intelligence (AI) program that rapidly predicts most protein structures as accurately as x-ray crystallography and cryo-EM can map them [2]. The AI program, called AlphaFold, predicts a protein’s structure by computationally modeling the amino acid interactions that govern its 3D shape.

Getting there wasn’t easy. While a complete de novo calculation of protein structure still seemed out of reach, investigators reasoned that they could kick start the modeling if known structures were provided as a training set to the AI program. Utilizing a computer network built around 128 machine learning processors, the AlphaFold system was created by first focusing on the 170,000 proteins with known structures in a reiterative process called deep learning. The process, which is inspired by the way neural networks in the human brain process information, enables computers to look for patterns in large collections of data. In this case, AlphaFold learned to predict the underlying physical structure of a protein within a matter of days. This breakthrough has the potential to accelerate the fields of structural biology and protein research, fueling progress throughout the sciences.

How Elite Controllers Keep HIV at Bay: The term “elite controller” might make some people think of video game whizzes. But here, it refers to the less than 1 percent of people living with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) who’ve somehow stayed healthy for years without taking antiretroviral drugs. In 2020, a team of NIH-supported researchers figured out why this is so.

In a study of 64 elite controllers, published in the journal Nature, the team discovered a link between their good health and where the virus has inserted itself in their genomes [3]. When a cell transcribes a gene where HIV has settled, this so-called “provirus,” can produce more virus to infect other cells. But if it settles in a part of a chromosome that rarely gets transcribed, sometimes called a gene desert, the provirus is stuck with no way to replicate. Although this discovery won’t cure HIV/AIDS, it points to a new direction for developing better treatment strategies.

In closing, 2020 presented more than its share of personal and social challenges. Among those challenges was a flood of misinformation about COVID-19 that confused and divided many communities and even families. That’s why the editors and writers at Science singled out “a second pandemic of misinformation” as its Breakdown of the Year. This divisiveness should concern all of us greatly, as COVID-19 cases continue to soar around the country and our healthcare gets stretched to the breaking point. I hope and pray that we will all find a way to come together, both in science and in society, as we move forward in 2021.

References:

[1] CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing for sickle cell disease and β-thalassemia. Frangoul H et al. N Engl J Med. 2020 Dec 5.

[2] ‘The game has changed.’ AI triumphs at protein folding. Service RF. Science. 04 Dec 2020.

[3] Distinct viral reservoirs in individuals with spontaneous control of HIV-1. Jiang C et al. Nature. 2020 Sep;585(7824):261-267.

Links:

COVID-19 Research (NIH)

2020 Science Breakthrough of the Year (American Association for the Advancement of Science, Washington, D.C)

See the Human Cardiovascular System in a Whole New Way

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Watch this brief video and you might guess you’re seeing an animated line drawing, gradually revealing a delicate take on a familiar system: the internal structures of the human body. But this movie doesn’t capture the work of a talented sketch artist. It was created using the first 3D, full-body imaging device using positron emission tomography (PET).

The device is called an EXPLORER (EXtreme Performance LOng axial REsearch scanneR) total-body PET scanner. By pairing this scanner with an advanced method for reconstructing images from vast quantities of data, the researchers can make movies.

For this movie in particular, the researchers injected small amounts of a short-lived radioactive tracer—an essential component of all PET scans—into the lower leg of a study volunteer. They then sat back as the scanner captured images of the tracer moving up the leg and into the body, where it enters the heart. The tracer moves through the heart’s right ventricle to the lungs, back through the left ventricle, and up to the brain. Keep watching, and, near the 30-second mark, you will see in closer focus a haunting capture of the beating heart.

This groundbreaking scanner was developed and tested by Jinyi Qi, Simon Cherry, Ramsey Badawi, and their colleagues at the University of California, Davis [1]. As the NIH-funded researchers reported recently in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, their new scanner can capture dynamic changes in the body that take place in a tenth of a second [2]. That’s faster than the blink of an eye!

This movie is composed of frames captured at 0.1-second intervals. It highlights a feature that makes this scanner so unique: its ability to visualize the whole body at once. Other medical imaging methods, including MRI, CT, and traditional PET scans, can be used to capture beautiful images of the heart or the brain, for example. But they can’t show what’s happening in the heart and brain at the same time.

The ability to capture the dynamics of radioactive tracers in multiple organs at once opens a new window into human biology. For example, the EXPLORER system makes it possible to measure inflammation that occurs in many parts of the body after a heart attack, as well as to study interactions between the brain and gut in Parkinson’s disease and other disorders.

EXPLORER also offers other advantages. It’s extra sensitive, which enables it to capture images other scanners would miss—and with a lower dose of radiation. It’s also much faster than a regular PET scanner, making it especially useful for imaging wiggly kids. And it expands the realm of research possibilities for PET imaging studies. For instance, researchers might repeatedly image a person with arthritis over time to observe changes that may be related to treatments or exercise.

Currently, the UC Davis team is working with colleagues at the University of California, San Francisco to use EXPLORER to enhance our understanding of HIV infection. Their preliminary findings show that the scanner makes it easier to capture where the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), the cause of AIDS, is lurking in the body by picking up on signals too weak to be seen on traditional PET scans.

While the research potential for this scanner is clearly vast, it also holds promise for clinical use. In fact, a commercial version of the scanner, called uEXPLORER, has been approved by the FDA and is in use at UC Davis [3]. The researchers have found that its improved sensitivity makes it much easier to detect cancers in patients who are obese and, therefore, harder to image well using traditional PET scanners.

As soon as the COVID-19 outbreak subsides enough to allow clinical research to resume, the researchers say they’ll begin recruiting patients with cancer into a clinical study designed to compare traditional PET and EXPLORER scans directly.

As these researchers, and other researchers around the world, begin to put this new scanner to use, we can look forward to seeing many more remarkable movies like this one. Imagine what they will reveal!

References:

[1] First human imaging studies with the EXPLORER total-body PET scanner. Badawi RD, Shi H, Hu P, Chen S, Xu T, Price PM, Ding Y, Spencer BA, Nardo L, Liu W, Bao J, Jones T, Li H, Cherry SR. J Nucl Med. 2019 Mar;60(3):299-303.

[2] Subsecond total-body imaging using ultrasensitive positron emission tomography. Zhang X, Cherry SR, Xie Z, Shi H, Badawi RD, Qi J. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2020 Feb 4;117(5):2265-2267.

[3] “United Imaging Healthcare uEXPLORER Total-body Scanner Cleared by FDA, Available in U.S. Early 2019.” Cision PR Newswire. January 22, 2019.

Links:

Positron Emission Tomography (PET) (NIH Clinical Center)

EXPLORER Total-Body PET Scanner (University of California, Davis)

Cherry Lab (UC Davis)

Badawi Lab (UC Davis Medical Center, Sacramento)

NIH Support: National Cancer Institute; National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering; Common Fund

Exploring Drug Repurposing for COVID-19 Treatment

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

It usually takes more than a decade to develop a safe, effective anti-viral therapy. But, when it comes to coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), we don’t have that kind of time. One way to speed the process may be to put some old drugs to work against this new disease threat. This is generally referred to as “drug repurposing.”

NIH has been doing everything possible to encourage screens of existing drugs that have been shown safe for human use. In a recent NIH-funded study in the journal Nature, researchers screened a chemical “library” that contained nearly 12,000 existing drug compounds for their potential activity against SARS-CoV-2, the novel coronavirus that causes COVID-19 [1]. The results? In tests in both non-human primate and human cell lines grown in laboratory conditions, 21 of these existing drugs showed potential for repurposing to thwart the novel coronavirus—13 of them at doses that likely could be safely given to people. The majority of these drugs have been tested in clinical trials for use in HIV, autoimmune diseases, osteoporosis, and other conditions.

These latest findings come from an international team led by Sumit Chanda, Sanford Burnham Prebys Medical Discovery Institute, La Jolla, CA. The researchers took advantage of a small-molecule drug library called ReFRAME [2], which was created in 2018 by Calibr, a non-profit drug discovery division of Scripps Research, La Jolla, CA.

In collaboration with Yuen Kwok-Yung’s team at the University of Hong Kong, the researchers first developed a high-throughput method that enabled them to screen rapidly each of the 11,987 drug compounds in the ReFRAME library for their potential to block SARS-CoV-2 in cells grown in the lab. The first round of testing narrowed the list of possible COVID-19 drugs to about 300. Next, using lower concentrations of the drugs in cells exposed to a second strain of SARS-CoV-2, they further narrowed the list to 100 compounds that could reliably limit growth of the coronavirus by at least 40 percent.

Generally speaking, an effective anti-viral drug is expected to show greater activity as its concentration is increased. So, Chanda’s team then tested those 100 drugs for evidence of such a dose-response relationship. Twenty-one of them passed this test. This group included remdesivir, a drug originally developed for Ebola virus disease and recently authorized by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for emergency use in the treatment of COVID-19. Remdesivir could now be considered a positive control.

These findings raised another intriguing question: Could any of the other drugs with a dose-response relationship work well in combination with remdesivir to block SARS-CoV-2 infection? Indeed, the researchers found that four of them could.

Further study showed that some of the most promising drugs on the list reduced the number of SARS-CoV-2 infected cells by 65 to 85 percent. The most potent of these was apilimod, a drug that has been evaluated in clinical trials for treating Crohn’s disease, rheumatoid arthritis, and other autoimmune conditions. Apilimod is now being evaluated in the clinic for its ability to prevent the progression of COVID-19. Another potential antiviral to emerge from the study is clofazimine, a 70-year old FDA-approved drug that is on the World Health Organization’s list of essential medicines for the treatment of leprosy.

Overall, the findings suggest that there may be quite a few existing drugs and/or experimental drugs fairly far along in the development pipeline that have potential to be repurposed for treating COVID-19. What’s more, some of them might also work well in combination with remdesivir, or perhaps other drugs, as treatment “cocktails,” such as those used to successfully treat HIV and hepatitis C.

This is just one of a wide variety of drug screening efforts that are underway, using different libraries and different assays to detect activity against SARS-CoV-2. The NIH’s National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences has established an open data portal to collect all of these data as quickly and openly as possible. As NIH continues its efforts to use the power of science to end the COVID-19 pandemic, it is critically important that we explore as many avenues as possible for developing diagnostics, treatments, and vaccines.

References:

[1] Discovery of SARS-CoV-2 antiviral drugs through large-scale compound repurposing. Riva L, Yuan S, Yin X, et al. Nature. 2020 Jul 24 [published online ahead of print]

[2] The ReFRAME library as a comprehensive drug repurposing library and its application to the treatment of cryptosporidiosis. Janes J, Young ME, Chen E, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2018;115(42):10750-10755.

Links:

Coronavirus (COVID-19) (NIH)

ReFRAMEdb (Scripps Research, La Jolla, CA)

The Chanda Lab (Sanford Burnham Prebys Medical Discovery Institute, La Jolla, CA)

Yuen Kwok-Yung (University of Hong Kong)

OpenData|Covid-19 (National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences/NIH)

NIH Support: National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases; National Institute of General Medical Sciences

Next Page