Colombia

Case Study Unlocks Clues to Rare Resilience to Alzheimer’s Disease

Posted on by Lawrence Tabak, D.D.S., Ph.D.

Biomedical breakthroughs most often involve slow and steady research in studies involving large numbers of people. But sometimes careful study of even just one truly remarkable person can lead the way to fascinating discoveries with far-reaching implications.

An NIH-funded case study published recently in the journal Nature Medicine falls into this far-reaching category [1]. The report highlights the world’s second person known to have an extreme resilience to a rare genetic form of early onset Alzheimer’s disease. These latest findings in a single man follow a 2019 report of a woman with similar resilience to developing symptoms of Alzheimer’s despite having the same strong genetic predisposition for the disease [2].

The new findings raise important new ideas about the series of steps that may lead to Alzheimer’s and its dementia. They’re also pointing the way to key parts of the brain for cognitive resilience—and potentially new treatment targets—that may one day help to delay or even stop progression of Alzheimer’s.

The man in question is a member of a well-studied extended family from the country of Colombia. This group of related individuals, or kindred, is the largest in the world with a genetic variant called the “Paisa” mutation (or Presenilin-1 E280A). This Paisa variant follows an autosomal dominant pattern of inheritance, meaning that those with a single altered copy of the rare variant passed down from one parent usually develop mild cognitive impairment around the age of 44. They typically advance to full-blown dementia around the age of 50 and rarely live past the age of 60. This contrasts with the most common form of Alzheimer’s, which usually begins after age 65.

The new findings come from a team led by Yakeel Quiroz, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston; Joseph Arboleda-Velasquez, Massachusetts Eye and Ear, Boston; Diego Sepulveda-Falla, University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany; and Francisco Lopera, University of Antioquia, Medellín, Colombia. Lopera first identified this family more than 30 years ago and has been studying them ever since.

In the new case report, the researchers identified a Colombian man who’d been married with two children and retired from his job as a mechanic in his early 60s. Despite carrying the Paisa mutation, his first cognitive assessment at age 67 showed he was cognitively intact, having limited difficulties with verbal learning skills or language. It wasn’t until he turned 70 that he was diagnosed with mild cognitive impairment—more than 20 years later than the expected age for this family—showing some decline in short-term memory and verbal fluency.

At age 73, he enrolled in the Colombia-Boston biomarker research study (COLBOS). This study is a collaborative project between the University of Antioquia and Massachusetts General Hospital involving approximately 6,000 individuals from the Paisa kindred. About 1,500 of those in the study carry the mutation that sets them up for early Alzheimer’s. As a member of the COLBOS study, the man underwent thorough neuroimaging tests to look for amyloid plaques and tau tangles, both of which are hallmarks of Alzheimer’s.

While this man died at age 74 with Alzheimer’s, the big question is: how did he stave off dementia for so long despite his poor genetic odds? The COLBOS study earlier identified a woman with a similar resilience to Alzheimer’s, which they traced to two copies of a rare, protective genetic variant called Christchurch. This variant affects a gene called apolipoprotein E (APOE3), which is well known for its influence on Alzheimer’s risk. However, the man didn’t carry this same protective variant.

The researchers still thought they’d find an answer in his genome and kept looking. While they found several variants of possible interest, they zeroed in on a single gene variant that they’ve named Reelin-COLBOS. What helped them to narrow it down to this variant is the man also had a sister with the Paisa mutation who only progressed to advanced dementia at age 72. It turned out, in addition to the Paisa variant, the siblings also shared an altered copy of the newly discovered Reelin-COLBOS variant.

This Reelin-COLBOS gene is known to encode a protein that controls signals to chemically modify tau proteins, which form tangles that build up over time in the Alzheimer’s brain and have been linked to memory loss. Reelin is also functionally related to APOE, the gene that was altered in the woman with extreme Alzheimer’s protection. Reelin and APOE both interact with common protein receptors in neurons. Together, the findings add to evidence that signaling pathways influencing tau play an important role in Alzheimer’s pathology and protection.

The neuroimaging exams conducted when the man was age 73 have offered further intriguing clues. They showed that his brain had extensive amyloid plaques. He also had tau tangles in some parts of his brain. But one brain region, called the entorhinal cortex, was notable for having a very minimal amount of those hallmark tau tangles.

The entorhinal cortex is a hub for memory, navigation, and the perception of time. Its degeneration also leads to cognitive impairment and dementia. Studies of the newly identified Reelin-COLBOS variant in Alzheimer’s mouse models also help to confirm that the variant offers its protection by diminishing the pathological modifications of tau.

Overall, the findings in this one individual and his sister highlight the Reelin pathway and brain region as promising targets for future study and development of Alzheimer’s treatments. Quiroz and her colleagues report that they are actively exploring treatment approaches inspired by the Christchurch and Reelin-COLBOS discoveries.

Of course, there’s surely more to discover from continued study of these few individuals and others like them. Other as yet undescribed genetic and environmental factors are likely at play. But the current findings certainly offer some encouraging news for those at risk for Alzheimer’s disease—and a reminder of how much can be learned from careful study of remarkable individuals.

References:

[1] Resilience to autosomal dominant Alzheimer’s disease in a Reelin-COLBOS heterozygous man. Lopera F, Marino C, Chandrahas AS, O’Hare M, Reiman EM, Sepulveda-Falla D, Arboleda-Velasquez JF, Quiroz YT, et al. Nat Med. 2023 May;29(5):1243-1252.

[2] Resistance to autosomal dominant Alzheimer’s disease in an APOE3 Christchurch homozygote: a case report. Arboleda-Velasquez JF, Lopera F, O’Hare M, Delgado-Tirado S, Tariot PN, Johnson KA, Reiman EM, Quiroz YT et al. Nat Med. 2019 Nov;25(11):1680-1683.

Links:

Alzheimer’s Disease & Related Dementias (National Institute on Aging/NIH)

“NIH Support Spurs Alzheimer’s Research in Colombia,” Global Health Matters, January/February 2014, Fogarty International Center/NIS

“COLBOS Study Reveals Mysteries of Alzheimer’s Disease,” NIH Record, August 19, 2022.

Yakeel Quiroz (Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston)

Joseph Arboleda-Velasquez (Massachusetts Eye and Ear, Harvard Medical School, Boston)

Diego Sepulveda-Falla Lab (University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany)

Francisco Lopera (University of Antioquia, Medellín, Colombia)

NIH Support: National Institute on Aging; National Eye Institute; National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke; Office of the Director

Mouse Study Finds Microbe Might Protect against Food Poisoning

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

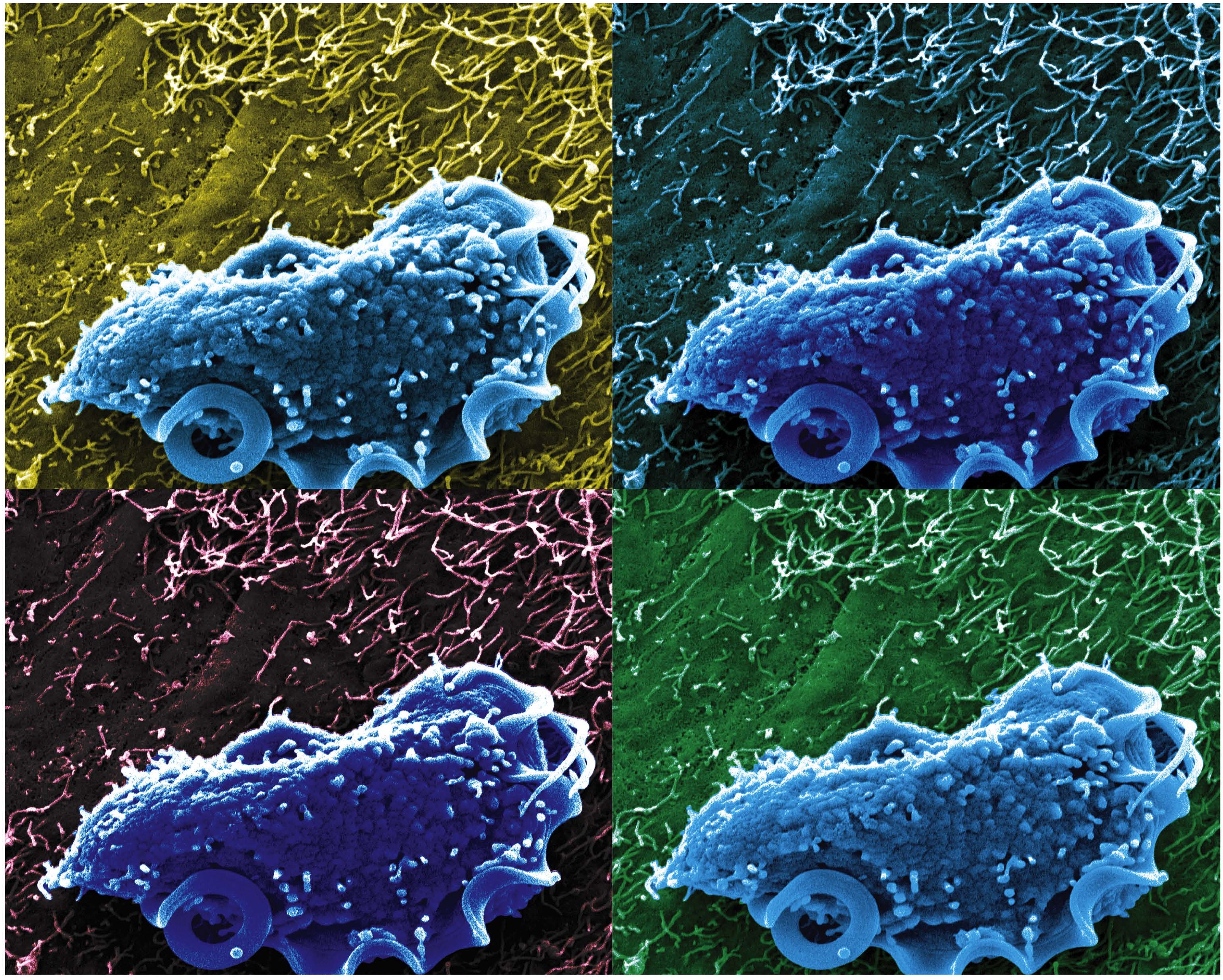

Caption: Scanning electron microscopy image of T. mu in the mouse colon.

Credit: Aleksey Chudnovskiy and Miriam Merad, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai

Recently, we humans have started to pay a lot more attention to the legions of bacteria that live on and in our bodies because of research that’s shown us the many important roles they play in everything from how we efficiently metabolize food to how well we fend off disease. And, as it turns out, bacteria may not be the only interior bugs with the power to influence our biology positively—a new study suggests that an entirely different kingdom of primarily single-celled microbes, called protists, may be in on the act.

In a study published in the journal Cell, an NIH-funded research team reports that it has identified a new protozoan, called Tritrichomonas musculis (T. mu), living inside the gut of laboratory mice. That sounds bad—but actually this little wriggler was potentially providing a positive benefit to the mice. Not only did T. mu appear to boost the animals’ immune systems, it spared them from the severe intestinal infection that typically occurs after eating food contaminated with toxic Salmonella bacteria. While it’s not yet clear if protists exist that can produce similar beneficial effects in humans, there is evidence that a close relative of T. mu frequently resides in the intestines of people around the world.

Creative Minds: Opening a Window on Alzheimer’s Before It Strikes

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

While attending college in her native Colombia, Yakeel T. Quiroz joined the Grupo de Neurociencias de Antioquia. This dedicated group of Colombian researchers, healthcare workers, and students has worked for many years with a large extended family in the northwestern district of Antioquia that is truly unique.

About half of the more than 5,000 family members inherit a gene mutation that predisposes them to what is known locally as “la bobera,” or “the foolishness,” a devastating form of early-onset Alzheimer’s disease. Those born with the mutation are cognitively healthy through their 20s, become forgetful in their 30s, and descend into full-blown Alzheimer’s disease by their mid-to-late 40s. Making matters worse, multiple family members sometimes are in different stages of dementia at the same time, including the caregiver attempting to hold the household together.

Quiroz, now a researcher at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, vowed never to forget these families. She hasn’t, working hard to understand early-onset Alzheimer’s disease and helping to establish the Forget Me Not Initiative to raise money for affected families. With an NIH Director’s Early Independence Award, Quiroz also recently launched her own lab to pursue an even broader scientific opportunity: discover subtle pre-symptomatic changes in the brain years before they give rise to detectable Alzheimer’s. What she learns will have application not only to detect and possibly treat early-onset Alzheimer’s in Colombia but also to understand the late-onset forms of the dementia that affect an estimated 35.6 million people worldwide.