schizophrenia

Brain Atlas Paves the Way for New Understanding of How the Brain Functions

Posted on by Lawrence Tabak, D.D.S., Ph.D.

When NIH launched The BRAIN Initiative® a decade ago, one of many ambitious goals was to develop innovative technologies for profiling single cells to create an open-access reference atlas cataloguing the human brain’s many parts. The ultimate goal wasn’t to produce a single, static reference map, but rather to capture a dynamic view of how the brain’s many cells of varied types are wired to work together in the healthy brain and how this picture may shift in those with neurological and mental health disorders.

So I’m now thrilled to report the publication of an impressive collection of work from hundreds of scientists in the BRAIN Initiative Cell Census Network (BICCN), detailed in more than 20 papers in Science, Science Advances, and Science Translational Medicine.1 Among many revelations, this unprecedented, international effort has characterized more than 3,000 human brain cell types. To put this into some perspective, consider that the human lung contains 61 cell types.2 The work has also begun to uncover normal variation in the brains of individual people, some of the features that distinguish various disease states, and distinctions among key parts of the human brain and those of our closely related primate cousins.

Of course, it’s not possible to do justice to this remarkable body of work or its many implications in the space of a single blog post. But to give you an idea of what’s been accomplished, some of these studies detail the primary effort to produce a comprehensive brain atlas, including defining the brain’s many cell types along with their underlying gene activity and the chemical modifications that turn gene activity up or down.3,4,5

Other studies in this collection take a deep dive into more specific brain areas. For instance, to capture normal variations among people, a team including Nelson Johansen, University of California, Davis, profiled cells in the neocortex—the outermost portion of the brain that’s responsible for many complex human behaviors.6 Overall, the work revealed a highly consistent cellular makeup from one person to the next. But it also highlighted considerable variation in gene activity, some of which could be explained by differences in age, sex and health. However, much of the observed variation remains unexplained, opening the door to more investigations to understand the meaning behind such brain differences and their role in making each of us who we are.

Yang Li, now at Washington University in St. Louis, and his colleagues analyzed 1.1 million cells from 42 distinct brain areas in samples from three adults.4 They explored various cell types with potentially important roles in neuropsychiatric disorders and were able to pinpoint specific cell types, genes and genetic switches that may contribute to the development of certain traits and disorders, including bipolar disorder, depression and schizophrenia.

Yet another report by Nikolas Jorstad, Allen Institute, Seattle, and colleagues delves into essential questions about what makes us human as compared to other primates like chimpanzees.7 Their comparisons of gene activity at the single-cell level in a specific area of the brain show that humans and other primates have largely the same brain cell types, but genes are activated differently in specific cell types in humans as compared to other primates. Those differentially expressed genes in humans often were found in portions of the genome that show evidence of rapid change over evolutionary time, suggesting that they play important roles in human brain function in ways that have yet to be fully explained.

All the data represented in this work has been made publicly accessible online for further study. Meanwhile, the effort to build a more finely detailed picture of even more brain cell types and, with it, a more complete understanding of human brain circuitry and how it can go awry continues in the BRAIN Initiative Cell Atlas Network (BICAN). As impressive as this latest installment is—in our quest to understand the human brain, brain disorders, and their treatment—we have much to look forward to in the years ahead.

References:

A list of all the papers part of the brain atlas research is available here: https://www.science.org/collections/brain-cell-census.

[1] M Maroso. A quest into the human brain. Science DOI: 10.1126/science.adl0913 (2023).

[2] L Sikkema, et al. An integrated cell atlas of the lung in health and disease. Nature Medicine DOI: 10.1038/s41591-023-02327-2 (2023).

[3] K Siletti, et al. Transcriptomic diversity of cell types across the adult human brain. Science DOI: 10.1126/science.add7046 (2023).

[4] Y Li, et al. A comparative atlas of single-cell chromatin accessibility in the human brain. Science DOI: 10.1126/science.adf7044 (2023).

[5] W Tian, et al. Single-cell DNA methylation and 3D genome architecture in the human brain. Science DOI: 10.1126/science.adf5357 (2023).

[6] N Johansen, et al. Interindividual variation in human cortical cell type abundance and expression. Science DOI: 10.1126/science.adf2359 (2023).

[7] NL Jorstad, et al. Comparative transcriptomics reveals human-specific cortical features. Science DOI: 10.1126/science.ade9516 (2023).

NIH Support: Projects funded through the NIH BRAIN Initiative Cell Consensus Network

How the Brain Differentiates the ‘Click,’ ‘Crack,’ or ‘Thud’ of Everyday Tasks

Posted on by Lawrence Tabak, D.D.S., Ph.D.

If you’ve been staying up late to watch the World Series, you probably spent those nine innings hoping for superstars Bryce Harper or José Altuve to square up a fastball and send it sailing out of the yard. Long-time baseball fans like me can distinguish immediately the loud crack of a home-run swing from the dull thud of a weak grounder.

Our brains have such a fascinating ability to discern “right” sounds from “wrong” ones in just an instant. This applies not only in baseball, but in the things that we do throughout the day, whether it’s hitting the right note on a musical instrument or pushing the car door just enough to click it shut without slamming.

Now, an NIH-funded team of neuroscientists has discovered what happens in the brain when one hears an expected or “right” sound versus a “wrong” one after completing a task. It turns out that the mammalian brain is remarkably good at predicting both when a sound should happen and what it ideally ought to sound like. Any notable mismatch between that expectation and the feedback, and the hearing center of the brain reacts.

It may seem intuitive that humans and other animals have this auditory ability, but researchers didn’t know how neurons in the brain’s auditory cortex, where sound is processed, make these snap judgements to learn complex tasks. In the study published in the journal Current Biology, David Schneider, New York University, New York, set out to understand how this familiar experience really works.

To do it, Schneider and colleagues, including postdoctoral fellow Nicholas Audette, looked to mice. They are a lot easier to study in the lab than humans and, while their brains aren’t miniature versions of our own, our sensory systems share many fundamental similarities because we are both mammals.

Of course, mice don’t go around hitting home runs or opening and closing doors. So, the researchers’ first step was training the animals to complete a task akin to closing the car door. To do it, they trained the animals to push a lever with their paws in just the right way to receive a reward. They also played a distinctive tone each time the lever reached that perfect position.

After making thousands of attempts and hearing the associated sound, the mice knew just what to do—and what it should sound like when they did it right. Their studies showed that, when the researchers removed the sound, played the wrong sound, or played the correct sound at the wrong time, the mice took notice and adjusted their actions, just as you might do if you pushed a car door shut and the resulting click wasn’t right.

To find out how neurons in the auditory cortex responded to produce the observed behaviors, Schneider’s team also recorded brain activity. Intriguingly, they found that auditory neurons hardly responded when a mouse pushed the lever and heard the sound they’d learned to expect. It was only when something about the sound was “off” that their auditory neurons suddenly crackled with activity.

As the researchers explained, it seems from these studies that the mammalian auditory cortex responds not to the sounds themselves but to how those sounds match up to, or violate, expectations. When the researchers canceled the sound altogether, as might happen if you didn’t push a car door hard enough to produce the familiar click shut, activity within a select group of auditory neurons spiked right as they should have heard the sound.

Schneider’s team notes that the same brain areas and circuitry that predict and process self-generated sounds in everyday tasks also play a role in conditions such as schizophrenia, in which people may hear voices or other sounds that aren’t there. The team hopes their studies will help to explain what goes wrong—and perhaps how to help—in schizophrenia and other neural disorders. Perhaps they’ll also learn more about what goes through the healthy brain when anticipating the satisfying click of a closed door or the loud crack of a World Series home run.

Reference:

[1] Precise movement-based predictions in the mouse auditory cortex. Audette NJ, Zhou WX, Chioma A, Schneider DM. Curr Biology. 2022 Oct 24.

Links:

How Do We Hear? (National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders/NIH)

Schizophrenia (National Institute of Mental Health/NIH)

David Schneider (New York University, New York)

NIH Support: National Institute of Mental Health; National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders

Groundbreaking Study Maps Key Brain Circuit

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Biologists have long wondered how neurons from different regions of the brain actually interconnect into integrated neural networks, or circuits. A classic example is a complex master circuit projecting across several regions of the vertebrate brain called the basal ganglia. It’s involved in many fundamental brain processes, such as controlling movement, thought, and emotion.

In a paper published recently in the journal Nature, an NIH-supported team working in mice has created a wiring diagram, or connectivity map, of a key component of this master circuit that controls voluntary movement. This groundbreaking map will guide the way for future studies of the basal ganglia’s direct connections with the thalamus, which is a hub for information going to and from the spinal cord, as well as its links to the motor cortex in the front of the brain, which controls voluntary movements.

This 3D animation drawn from the paper’s findings captures the biological beauty of these intricate connections. It starts out zooming around four of the six horizontal layers of the motor cortex. At about 6 seconds in, the video focuses on nerve cell projections from the thalamus (blue) connecting to cortex nerve cells that provide input to the basal ganglia (green). It also shows connections to the cortex nerve cells that input to the thalamus (red).

At about 25 seconds, the video scans back to provide a quick close-up of the cell bodies (green and red bulges). It then zooms out to show the broader distribution of nerve cells within the cortex layers and the branched fringes of corticothalamic nerve cells (red) at the top edge of the cortex.

The video comes from scientific animator Jim Stanis, University of Southern California Mark and Mary Stevens Neuroimaging and Informatics Institute, Los Angeles. He collaborated with Nick Foster, lead author on the Nature paper and a research scientist in the NIH-supported lab of Hong-Wei Dong at the University of California, Los Angeles.

The two worked together to bring to life hundreds of microscopic images of this circuit, known by the unusually long, hyphenated name: the cortico-basal ganglia-thalamic loop. It consists of a series of subcircuits that feed into a larger signaling loop.

The subcircuits in the loop make it possible to connect thinking with movement, helping the brain learn useful sequences of motor activity. The looped subcircuits also allow the brain to perform very complex tasks such as achieving goals (completing a marathon) and adapting to changing circumstances (running uphill or downhill).

Although scientists had long assumed the cortico-basal ganglia-thalamic loop existed and formed a tight, closed loop, they had no real proof. This new research, funded through NIH’s Brain Research Through Advancing Innovative Neurotechnologies® (BRAIN) Initiative, provides that proof showing anatomically that the nerve cells physically connect, as highlighted in this video. The research also provides electrical proof through tests that show stimulating individual segments activate the others.

Detailed maps of neural circuits are in high demand. That’s what makes results like these so exciting to see. Researchers can now better navigate this key circuit not only in mice but other vertebrates, including humans. Indeed, the cortico-basal ganglia-thalamic loop may be involved in a number of neurological and neuropsychiatric conditions, including Huntington’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, schizophrenia, and addiction. In the meantime, Stanis, Foster, and colleagues have left us with a very cool video to watch.

Reference:

[1] The mouse cortico-basal ganglia-thalamic network. Foster NN, Barry J, Korobkova L, Garcia L, Gao L, Becerra M, Sherafat Y, Peng B, Li X, Choi JH, Gou L, Zingg B, Azam S, Lo D, Khanjani N, Zhang B, Stanis J, Bowman I, Cotter K, Cao C, Yamashita S, Tugangui A, Li A, Jiang T, Jia X, Feng Z, Aquino S, Mun HS, Zhu M, Santarelli A, Benavidez NL, Song M, Dan G, Fayzullina M, Ustrell S, Boesen T, Johnson DL, Xu H, Bienkowski MS, Yang XW, Gong H, Levine MS, Wickersham I, Luo Q, Hahn JD, Lim BK, Zhang LI, Cepeda C, Hintiryan H, Dong HW. Nature. 2021;598(7879):188-194.

Links:

Brain Basics: Know Your Brain (National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke/NIH)

Dong Lab (University of California, Los Angeles)

Mark and Mary Stevens Neuroimaging and Informatics Institute (University of Southern California, Los Angeles)

The Brain Research Through Advancing Innovative Neurotechnologies® (BRAIN) Initiative (NIH)

NIH Support: Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development; National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders; National Institute of Mental Health

New Technology Opens Evolutionary Window into Brain Development

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

One of the great mysteries in biology is how we humans ended up with such large, complex brains. In search of clues, researchers have spent years studying the protein-coding genes activated during neurodevelopment. But some answers may also be hiding in non-coding regions of the human genome, where sequences called regulatory elements increase or decrease the activity of genes.

A fascinating example involves a type of regulatory element called a human accelerated region (HAR). Although “human” is part of this element’s name, it turns out that the genomes of all vertebrates—not just humans—contain the DNA segments now designated as HARs.

In most organisms, HARs show a relatively low rate of mutation, which means these regulatory elements have been highly conserved across species throughout evolutionary time [1]. The big exception is Homo sapiens, in which HARs have exhibited a much higher rate of mutations.

The accelerated rate of HARs mutations observed in humans suggest that, over the course of very long periods of time, these genomic changes might have provided our species with some sort of evolutionary advantage. What might that be? Many have speculated the advantage might involve the brain because HARs are often associated with genes involved in neurodevelopment. Now, in a paper published in the journal Neuron, an NIH-supported team confirms that’s indeed the case [2].

In the new work, researchers found that about half of the HARs in the human genome influence the activity, or expression, of protein-coding genes in neural cells and tissues during the brain’s development [3]. The researchers say their study—the most comprehensive to date of the 3,171 HARs in the human genome—firmly establishes that this type of regulatory element helps to drive patterns of neurodevelopmental gene activity specific to humans.

Yet to be determined is precisely how HARs affect the development of the human brain. The quest to uncover these details will no doubt shed new light on fundamental questions about the brain, its billions of neurons, and their trillions of interconnections. For example, why does human neural development span decades, longer than the life spans of most primates and other mammals? Answering such questions could also reveal new clues into a range of cognitive and behavioral disorders. In fact, early research has already made tentative links between HARs and neurodevelopmental conditions such as autism spectrum disorder and schizophrenia [3].

The latest work was led by Kelly Girskis, Andrew Stergachis, and Ellen DeGennaro, all of whom were in the lab of Christopher Walsh while working on the project. An NIH grantee, Walsh is director of the Allen Discovery Center for Brain Evolution at Boston Children’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, which is supported by the Paul G. Allen Foundation Frontiers Group, and is an Investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Though HARs have been studied since 2006, one of the big challenges in systematically assessing them has been technological. The average length of a HAR is about 269 bases of DNA, but current technologies for assessing function can only easily analyze DNA molecules that span 150 bases or less.

Ryan Doan, who was then in the Walsh Lab, and his colleagues solved the problem by creating a new machine called CaptureMPRA. (MPRA is short for “massively parallel reporter assays.”) This technological advance cleverly barcodes HARs and, more importantly, makes it possible to analyze HARs up to about 500 bases in length.

Using CaptureMPRA technology in tandem with cell culture studies, researchers rolled up their sleeves and conducted comprehensive, full-sequence analyses of more than 3,000 HARs. In their initial studies, primarily in neural cells, they found nearly half of human HARs are active to drive gene expression in cell culture. Of those, 42 percent proved to have increased ability to enhance gene expression compared to their orthologues, or counterparts, in chimpanzees.

Next, the team integrated these data with an existing epigenetic dataset derived from developing human brain cells, as well as additional datasets generated from sorted brain cell types. They found that many HARs appeared to have the ability to increase the activity of protein-coding genes, while a smaller—but very significant—subset of the HARs appeared to be enhancing gene expression specifically in neural progenitor cells, which are responsible for making various neural cell types.

The data suggest that as the human HAR sequences mutated and diverged from other mammals, they increased their ability to enhance or sometimes suppress the activity of certain genes in neural cells. To illustrate this point, the researchers focused on two HARs that appear to interact specifically with a gene referred to as R17. This gene can have highly variable gene expression patterns not only in different human cell types, but also in cells from other vertebrates and non-vertebrates.

In the human cerebral cortex, the outermost part of the brain that’s responsible for complex behaviors, R17 is expressed only in neural progenitor cells and only at specific time points. The researchers found that R17 slows the progression of neural progenitor cells through the cell cycle. That might seem strange, given the billions of neurons that need to be made in the cortex. But it’s consistent with the biology. In the human, it takes more than 130 days for the cortex to complete development, compared to about seven days in the mouse.

Clearly, to learn more about how the human brain evolved, researchers will need to look for clues in many parts of the genome at once, including its non-coding regions. To help researchers navigate this challenging terrain, the Walsh team has created an online resource displaying their comprehensive HAR data. It will appear soon, under the name HAR Hub, on the University of California Santa Cruz Genome Browser.

References:

[1] An RNA gene expressed during cortical development evolved rapidly in humans. Pollard KS, Salama SR, Lambert N, Lambot MA, Coppens S, Pedersen JS, Katzman S, King B, Onodera C, Siepel A, Kern AD, Dehay C, Igel H, Ares M Jr, Vanderhaeghen P, Haussler D. Nature. 2006 Sep 14;443(7108):167-72.

[2] Rewiring of human neurodevelopmental gene regulatory programs by human accelerated regions. Girskis KM, Stergachis AB, DeGennaro EM, Doan RN, Qian X, Johnson MB, Wang PP, Sejourne GM, Nagy MA, Pollina EA, Sousa AMM, Shin T, Kenny CJ, Scotellaro JL, Debo BM, Gonzalez DM, Rento LM, Yeh RC, Song JHT, Beaudin M, Fan J, Kharchenko PV, Sestan N, Greenberg ME, Walsh CA. Neuron. 2021 Aug 25:S0896-6273(21)00580-8.

[3] Mutations in human accelerated regions disrupt cognition and social behavior. Doan RN, Bae BI, Cubelos B, Chang C, Hossain AA, Al-Saad S, Mukaddes NM, Oner O, Al-Saffar M, Balkhy S, Gascon GG; Homozygosity Mapping Consortium for Autism, Nieto M, Walsh CA. Cell. 2016 Oct 6;167(2):341-354.

Links:

Christopher Walsh Laboratory (Boston Children’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School)

The Paul G. Allen Foundation Frontiers Group (Seattle)

NIH Support: National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke; National Institute of Mental Health; National Institute of General Medical Sciences; National Cancer Institute

A Real-Time Look at Value-Based Decision Making

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

All of us make many decisions every day. For most things, such as which jacket to wear or where to grab a cup of coffee, there’s usually no right answer, so we often decide using values rooted in our past experiences. Now, neuroscientists have identified the part of the mammalian brain that stores information essential to such value-based decision making.

Researchers zeroed in on this particular brain region, known as the retrosplenial cortex (RSC), by analyzing movies—including the clip shown about 32 seconds into this video—that captured in real time what goes on in the brains of mice as they make decisions. Each white circle is a neuron, and the flickers of light reflect their activity: the brighter the light, the more active the neuron at that point in time.

All told, the NIH-funded team, led by Ryoma Hattori and Takaki Komiyama, University of California at San Diego, La Jolla, made recordings of more than 45,000 neurons across six regions of the mouse brain [1]. Neural activity isn’t usually visible. But, in this case, researchers used mice that had been genetically engineered so that their neurons, when activated, expressed a protein that glowed.

Their system was also set up to encourage the mice to make value-based decisions, including choosing between two drinking tubes, each with a different probability of delivering water. During this decision-making process, the RSC proved to be the region of the brain where neurons persistently lit up, reflecting how the mouse evaluated one option over the other.

The new discovery, described in the journal Cell, comes as something of a surprise to neuroscientists because the RSC hadn’t previously been implicated in value-based decisions. To gather additional evidence, the researchers turned to optogenetics, a technique that enabled them to use light to inactivate neurons in the RSC’s of living animals. These studies confirmed that, with the RSC turned off, the mice couldn’t retrieve value information based on past experience.

The researchers note that the RSC is heavily interconnected with other key brain regions, including those involved in learning, memory, and controlling movement. This indicates that the RSC may be well situated to serve as a hub for storing value information, allowing it to be accessed and acted upon when it is needed.

The findings are yet another amazing example of how advances coming out of the NIH-led Brain Research through Advancing Innovative Neurotechnologies® (BRAIN) Initiative are revolutionizing our understanding of the brain. In the future, the team hopes to learn more about how the RSC stores this information and sends it to other parts of the brain. They note that it will also be important to explore how activity in this brain area may be altered in schizophrenia, dementia, substance abuse, and other conditions that may affect decision-making abilities. It will also be interesting to see how this develops during childhood and adolescence.

Reference:

[1] Area-Specificity and Plasticity of History-Dependent Value Coding During Learning. Hattori R, Danskin B, Babic Z, Mlynaryk N, Komiyama T. Cell. 2019 Jun 13;177(7):1858-1872.e15.

Links:

Brain Research through Advancing Innovative Neurotechnologies® (BRAIN) Initiative (NIH)

Komiyama Lab (UCSD, La Jolla)

NIH Support: National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke; National Eye Institute; National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders

Multiplex Rainbow Technology Offers New View of the Brain

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

The NIH-led Brain Research through Advancing Innovative Neurotechnologies® (BRAIN) Initiative is revolutionizing our understanding of how the brain works through its creation of new imaging tools. One of the latest advances—used to produce this rainbow of images—makes it possible to view dozens of proteins in rapid succession in a single tissue sample containing thousands of neural connections, or synapses.

Apart from their colors, most of these images look nearly identical at first glance. But, upon closer inspection, you’ll see some subtle differences among them in both intensity and pattern. That’s because the images capture different proteins within the complex network of synapses—and those proteins may be present in that network in different amounts and locations. Such findings may shed light on key differences among synapses, as well as provide new clues into the roles that synaptic proteins may play in schizophrenia and various other neurological disorders.

Synapses contain hundreds of proteins that regulate the release of chemicals called neurotransmitters, which allow neurons to communicate. Each synaptic protein has its own specific job in the process. But there have been longstanding technical difficulties in observing synaptic proteins at work. Conventional fluorescence microscopy can visualize at most four proteins in a synapse.

As described in Nature Communications [1], researchers led by Mark Bathe, Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), Cambridge, and Jeffrey Cottrell, Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard, Cambridge, have just upped this number considerably while delivering high quality images. They did it by adapting an existing imaging method called DNA PAINT [2]. The researchers call their adapted method PRISM. It is short for: Probe-based Imaging for Sequential Multiplexing.

Here’s how it works: First, researchers label proteins or other molecules of interest using antibodies that recognize those proteins. Those antibodies include a unique DNA probe that helps with the next important step: making the proteins visible under a microscope.

To do it, they deliver short snippets of complementary fluorescent DNA, which bind the DNA-antibody probes. While each protein of interest is imaged separately, researchers can easily wash the probes from a sample to allow a series of images to be generated, each capturing a different protein of interest.

In the original DNA PAINT, the DNA strands bind and unbind periodically to create a blinking fluorescence that can be captured using super-resolution microscopy. But that makes the process slow, requiring about half an hour for each protein.

To speed things up with PRISM, Bathe and his colleagues altered the fluorescent DNA probes. They used synthetic DNA that’s specially designed to bind more tightly or “lock” to the DNA-antibody. This gives a much brighter signal without the blinking effect. As a result, the imaging can be done faster, though at slightly lower resolution.

Though the team now captures images of 12 proteins within a sample in about an hour, this is just a start. As more DNA-antibody probes are developed for synaptic proteins, the team can readily ramp up this number to 30 protein targets.

Thanks to the BRAIN Initiative, researchers now possess a powerful new tool to study neurons. PRISM will help them learn more mechanistically about the inner workings of synapses and how they contribute to a range of neurological conditions.

References:

[1] Multiplexed and high-throughput neuronal fluorescence imaging with diffusible probes. Guo SM, Veneziano R, Gordonov S, Li L, Danielson E, Perez de Arce K, Park D, Kulesa AB, Wamhoff EC, Blainey PC, Boyden ES, Cottrell JR, Bathe M. Nat Commun. 2019 Sep 26;10(1):4377.

[2] Super-resolution microscopy with DNA-PAINT. Schnitzbauer J, Strauss MT, Schlichthaerle T, Schueder F, Jungmann R. Nat Protoc. 2017 Jun;12(6):1198-1228.

Links:

Schizophrenia (National Institute of Mental Health)

Mark Bathe (Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge)

Jeffrey Cottrell (Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard, Cambridge)

Brain Research through Advancing Innovative Neurotechnologies® (BRAIN) Initiative (NIH)

NIH Support: National Institute of Mental Health; National Human Genome Research Institute; National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke; National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences

Study Shows Genes Unique to Humans Tied to Bigger Brains

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

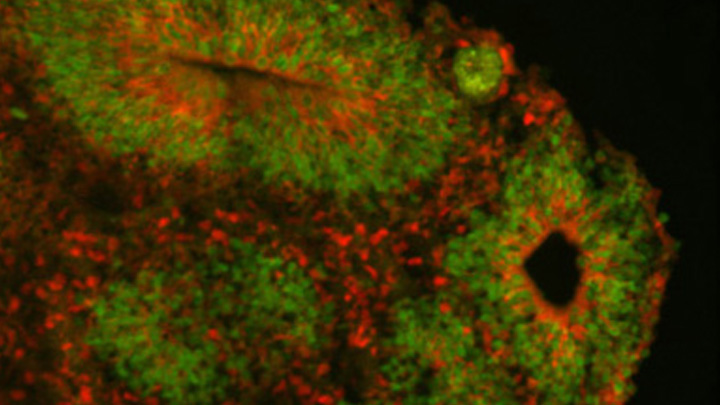

Caption: Cortical organoid, showing radial glial stem cells (green) and cortical neurons (red).

Credit: Sofie Salama, University of California, Santa Cruz

In seeking the biological answer to the question of what it means to be human, the brain’s cerebral cortex is a good place to start. This densely folded, outer layer of grey matter, which is vastly larger in Homo sapiens than in other primates, plays an essential role in human consciousness, language, and reasoning.

Now, an NIH-funded team has pinpointed a key set of genes—found only in humans—that may help explain why our species possesses such a large cerebral cortex. Experimental evidence shows these genes prolong the development of stem cells that generate neurons in the cerebral cortex, which in turn enables the human brain to produce more mature cortical neurons and, thus, build a bigger cerebral cortex than our fellow primates.

That sounds like a great advantage for humans! But there’s a downside. Researchers found the same genomic changes that facilitated the expansion of the human cortex may also render our species more susceptible to certain rare neurodevelopmental disorders.

Next Page