humans

Study Shows Genes Unique to Humans Tied to Bigger Brains

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

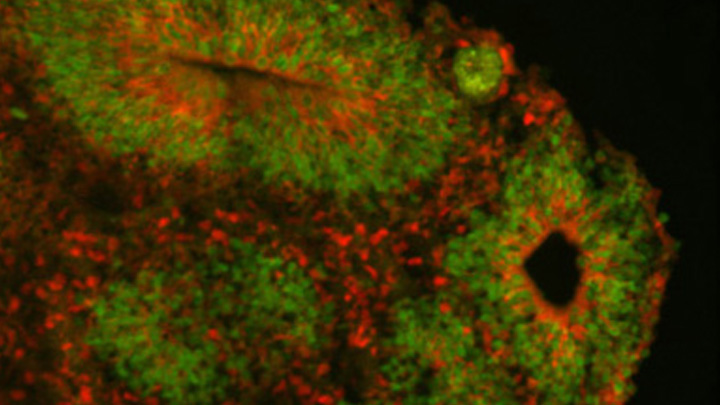

Caption: Cortical organoid, showing radial glial stem cells (green) and cortical neurons (red).

Credit: Sofie Salama, University of California, Santa Cruz

In seeking the biological answer to the question of what it means to be human, the brain’s cerebral cortex is a good place to start. This densely folded, outer layer of grey matter, which is vastly larger in Homo sapiens than in other primates, plays an essential role in human consciousness, language, and reasoning.

Now, an NIH-funded team has pinpointed a key set of genes—found only in humans—that may help explain why our species possesses such a large cerebral cortex. Experimental evidence shows these genes prolong the development of stem cells that generate neurons in the cerebral cortex, which in turn enables the human brain to produce more mature cortical neurons and, thus, build a bigger cerebral cortex than our fellow primates.

That sounds like a great advantage for humans! But there’s a downside. Researchers found the same genomic changes that facilitated the expansion of the human cortex may also render our species more susceptible to certain rare neurodevelopmental disorders.

Of Mice and Men: Study Pinpoints Genes Essential for Life

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Credit: National Human Genome Research Institute, NIH

Many people probably think of mice as unwanted household pests. But over more than a century, mice have proven to be incredibly valuable in medical research. One of many examples is how studies in mice are now helping researchers understand how mammalian genomes work, including the human genome. Scientists have spent decades inactivating, or “knocking out,” individual genes in laboratory mice to learn which tissues or organs are affected when a specific gene is out of order, providing valuable clues about its function.

More than a decade ago, NIH initiated a project called KOMP—the Knockout Mouse Project [1]. The goal was to use homologous recombination (exchange of similar or identical DNA) in embryonic stem cells from a standard mouse strain to knock out all of the mouse protein-coding genes. That work has led to wide availability of such cell lines to investigators with interest in specific genes, saving time and money. But it’s one thing to have a cell line with the gene knocked out, it’s even more interesting (and challenging) to determine the phenotype, or observable characteristics, of each knockout. To speed up that process in a scientifically rigorous and systematic manner, NIH and other research funding agencies teamed to launch an international research consortium to turn those embryonic stem cells into mice, and ultimately to catalogue the functions of the roughly 20,000 genes that mice and humans share. The consortium has just released an analysis of the phenotypes of the first 1,751 new lines of unique “knockout mice” with much more to come in the months ahead. This initial work confirms that about a third of all protein-coding genes are essential for live birth, helping to fill in a major gap in our understanding of the genome.