Autism Spectrum Disorder

New Technology Opens Evolutionary Window into Brain Development

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

One of the great mysteries in biology is how we humans ended up with such large, complex brains. In search of clues, researchers have spent years studying the protein-coding genes activated during neurodevelopment. But some answers may also be hiding in non-coding regions of the human genome, where sequences called regulatory elements increase or decrease the activity of genes.

A fascinating example involves a type of regulatory element called a human accelerated region (HAR). Although “human” is part of this element’s name, it turns out that the genomes of all vertebrates—not just humans—contain the DNA segments now designated as HARs.

In most organisms, HARs show a relatively low rate of mutation, which means these regulatory elements have been highly conserved across species throughout evolutionary time [1]. The big exception is Homo sapiens, in which HARs have exhibited a much higher rate of mutations.

The accelerated rate of HARs mutations observed in humans suggest that, over the course of very long periods of time, these genomic changes might have provided our species with some sort of evolutionary advantage. What might that be? Many have speculated the advantage might involve the brain because HARs are often associated with genes involved in neurodevelopment. Now, in a paper published in the journal Neuron, an NIH-supported team confirms that’s indeed the case [2].

In the new work, researchers found that about half of the HARs in the human genome influence the activity, or expression, of protein-coding genes in neural cells and tissues during the brain’s development [3]. The researchers say their study—the most comprehensive to date of the 3,171 HARs in the human genome—firmly establishes that this type of regulatory element helps to drive patterns of neurodevelopmental gene activity specific to humans.

Yet to be determined is precisely how HARs affect the development of the human brain. The quest to uncover these details will no doubt shed new light on fundamental questions about the brain, its billions of neurons, and their trillions of interconnections. For example, why does human neural development span decades, longer than the life spans of most primates and other mammals? Answering such questions could also reveal new clues into a range of cognitive and behavioral disorders. In fact, early research has already made tentative links between HARs and neurodevelopmental conditions such as autism spectrum disorder and schizophrenia [3].

The latest work was led by Kelly Girskis, Andrew Stergachis, and Ellen DeGennaro, all of whom were in the lab of Christopher Walsh while working on the project. An NIH grantee, Walsh is director of the Allen Discovery Center for Brain Evolution at Boston Children’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, which is supported by the Paul G. Allen Foundation Frontiers Group, and is an Investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Though HARs have been studied since 2006, one of the big challenges in systematically assessing them has been technological. The average length of a HAR is about 269 bases of DNA, but current technologies for assessing function can only easily analyze DNA molecules that span 150 bases or less.

Ryan Doan, who was then in the Walsh Lab, and his colleagues solved the problem by creating a new machine called CaptureMPRA. (MPRA is short for “massively parallel reporter assays.”) This technological advance cleverly barcodes HARs and, more importantly, makes it possible to analyze HARs up to about 500 bases in length.

Using CaptureMPRA technology in tandem with cell culture studies, researchers rolled up their sleeves and conducted comprehensive, full-sequence analyses of more than 3,000 HARs. In their initial studies, primarily in neural cells, they found nearly half of human HARs are active to drive gene expression in cell culture. Of those, 42 percent proved to have increased ability to enhance gene expression compared to their orthologues, or counterparts, in chimpanzees.

Next, the team integrated these data with an existing epigenetic dataset derived from developing human brain cells, as well as additional datasets generated from sorted brain cell types. They found that many HARs appeared to have the ability to increase the activity of protein-coding genes, while a smaller—but very significant—subset of the HARs appeared to be enhancing gene expression specifically in neural progenitor cells, which are responsible for making various neural cell types.

The data suggest that as the human HAR sequences mutated and diverged from other mammals, they increased their ability to enhance or sometimes suppress the activity of certain genes in neural cells. To illustrate this point, the researchers focused on two HARs that appear to interact specifically with a gene referred to as R17. This gene can have highly variable gene expression patterns not only in different human cell types, but also in cells from other vertebrates and non-vertebrates.

In the human cerebral cortex, the outermost part of the brain that’s responsible for complex behaviors, R17 is expressed only in neural progenitor cells and only at specific time points. The researchers found that R17 slows the progression of neural progenitor cells through the cell cycle. That might seem strange, given the billions of neurons that need to be made in the cortex. But it’s consistent with the biology. In the human, it takes more than 130 days for the cortex to complete development, compared to about seven days in the mouse.

Clearly, to learn more about how the human brain evolved, researchers will need to look for clues in many parts of the genome at once, including its non-coding regions. To help researchers navigate this challenging terrain, the Walsh team has created an online resource displaying their comprehensive HAR data. It will appear soon, under the name HAR Hub, on the University of California Santa Cruz Genome Browser.

References:

[1] An RNA gene expressed during cortical development evolved rapidly in humans. Pollard KS, Salama SR, Lambert N, Lambot MA, Coppens S, Pedersen JS, Katzman S, King B, Onodera C, Siepel A, Kern AD, Dehay C, Igel H, Ares M Jr, Vanderhaeghen P, Haussler D. Nature. 2006 Sep 14;443(7108):167-72.

[2] Rewiring of human neurodevelopmental gene regulatory programs by human accelerated regions. Girskis KM, Stergachis AB, DeGennaro EM, Doan RN, Qian X, Johnson MB, Wang PP, Sejourne GM, Nagy MA, Pollina EA, Sousa AMM, Shin T, Kenny CJ, Scotellaro JL, Debo BM, Gonzalez DM, Rento LM, Yeh RC, Song JHT, Beaudin M, Fan J, Kharchenko PV, Sestan N, Greenberg ME, Walsh CA. Neuron. 2021 Aug 25:S0896-6273(21)00580-8.

[3] Mutations in human accelerated regions disrupt cognition and social behavior. Doan RN, Bae BI, Cubelos B, Chang C, Hossain AA, Al-Saad S, Mukaddes NM, Oner O, Al-Saffar M, Balkhy S, Gascon GG; Homozygosity Mapping Consortium for Autism, Nieto M, Walsh CA. Cell. 2016 Oct 6;167(2):341-354.

Links:

Christopher Walsh Laboratory (Boston Children’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School)

The Paul G. Allen Foundation Frontiers Group (Seattle)

NIH Support: National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke; National Institute of Mental Health; National Institute of General Medical Sciences; National Cancer Institute

The Amazing Brain: Tracking Molecular Events with Calling Cards

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

In days mostly gone by, it was fashionable in some circles for people to hand out calling cards to mark their arrival at special social events. This genteel human tradition is now being adapted to the lab to allow certain benign viruses to issue their own high-tech calling cards and mark their arrival at precise locations in the genome. These special locations show where there’s activity involving transcription factors, specialized proteins that switch genes on and off and help determine cell fate.

The idea is that myriad, well-placed calling cards can track brain development over time in mice and detect changes in transcription factor activity associated with certain neuropsychiatric disorders. This colorful image, which won first place in this year’s Show Us Your BRAINs! Photo and Video contest, provides a striking display of these calling cards in action in living brain tissue.

The image comes from Allen Yen, a PhD candidate in the lab of Joseph Dougherty, collaborating with the nearby lab of Rob Mitra. Both labs are located in the Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis.

Yen and colleagues zoomed in on this section of mouse brain tissue under a microscope to capture dozens of detailed images that they then stitched together to create this high-resolution overview. The image shows neural cells (red) and cell nuclei (blue). But focus in on the neural cells (green) concentrated in the brain’s outer cortex (top) and hippocampus (two lobes in the upper center). They’ve been labelled with calling cards that were dropped off by adeno-associated virus [1].

Once dropped off, a calling card doesn’t bear a pretentious name or title. Rather, the calling card, is a small mobile snippet of DNA called a transposon. It gets dropped off with the other essential component of the technology: a specialized enzyme called a transposase, which the researchers fuse to one of many specific transcription factors of interest.

Each time one of these transcription factors of interest binds DNA to help turn a gene on or off, the attached transposase “grabs” a transposon calling card and inserts it into the genome. As a result, it leaves behind a permanent record of the interaction.

What’s also nice is the calling cards are programmed to give away their general locations. That’s because they encode a fluorescent marker (in this image, it’s a green fluorescent protein). In fact, Yen and colleagues could look under a microscope and tell from all the green that their calling card technology was in place and working as intended.

The final step, though, was to find out precisely where in the genome those calling cards had been left. For this, the researchers used next-generation sequencing to produce a cumulative history and map of each and every calling card dropped off in the genome.

These comprehensive maps allow them to identify important DNA-protein binding events well after the fact. This innovative technology also enables scientists to attribute past molecular interactions with observable developmental outcomes in a way that isn’t otherwise possible.

While the Mitra and Dougherty labs continue to improve upon this technology, it’s already readily adaptable to answer many important questions about the brain and brain disorders. In fact, Yen is now applying the technology to study neurodevelopment in mouse models of neuropsychiatric disorders, specifically autism spectrum disorder (ASD) [2]. This calling card technology also is available for any lab to deploy for studying a transcription factor of interest.

This research is supported by the Brain Research through Advancing Innovative Neurotechnologies® (BRAIN) Initiative. One of the major goals of BRAIN Initiative is to accelerate the development and application of innovative technologies to gain new understanding of the brain. This award-winning image is certainly a prime example of striving to meet this goal. I’ll look forward to what these calling cards will tell us in the future about ASD and other important neurodevelopmental conditions affecting the brain.

References:

[1] A viral toolkit for recording transcription factor-DNA interactions in live mouse tissues. Cammack AJ, Moudgil A, Chen J, Vasek MJ, Shabsovich M, McCullough K, Yen A, Lagunas T, Maloney SE, He J, Chen X, Hooda M, Wilkinson MN, Miller TM, Mitra RD, Dougherty JD. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2020 May 5;117(18):10003-10014.

[2] A MYT1L Syndrome mouse model recapitulates patient phenotypes and reveals altered brain development due to disrupted neuronal maturation. Jiayang Chen, Mary E. Lambo, Xia Ge, Joshua T. Dearborn, Yating Liu, Katherine B. McCullough, Raylynn G. Swift, Dora R. Tabachnick, Lucy Tian, Kevin Noguchi, Joel R. Garbow, John N. Constantino. bioRxiv. May 27, 2021.

Links:

Brain Research through Advancing Innovative Neurotechnologies® (BRAIN) Initiative (NIH)

Autism Spectrum Disorder (National Institute of Mental Health/NIH)

Dougherty Lab (Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis)

Mitra Lab (Washington University School of Medicine)

Show Us Your BRAINs! Photo and Video Contest (BRAIN Initiative/NIH)

NIH Support: National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke; National Institute of Mental Health; National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences; National Human Genome Research Institute; National Institute of General Medical Sciences

Could A Gut-Brain Connection Help Explain Autism?

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

You might think nutrient-sensing cells in the human gastrointestinal (GI) tract would have no connection whatsoever to autism spectrum disorder (ASD). But if Diego Bohórquez’s “big idea” is correct, these GI cells, called neuropods, could one day help to provide a direct link into understanding and treating some aspects of autism and other brain disorders.

Bohórquez, a researcher at Duke University, Durham, NC, recently discovered that cells in the intestine, previously known for their hormone-releasing ability, form extensions similar to neurons. He also found that those extensions connect to nerve fibers in the gut, which relay signals to the vagus nerve and onward to the brain. In fact, he found that those signals reach the brain in milliseconds [1].

Bohórquez has dedicated his lab to studying this direct, high-speed hookup between gut and brain and its impact on nutrient sensing, eating, and other essential behaviors. Now, with support from a 2019 NIH Director’s New Innovator Award, he will also explore the potential for treating autism and other brain disorders with drugs that act on the gut.

Bohórquez became interested in autism and its possible link to the gut-brain connection after a chance encounter with Geraldine Dawson, director of the Duke Center for Autism and Brain Development. Dawson mentioned that autism typically affects multiple organ systems.

With further reading, he discovered that kids with autism frequently cope with GI issues, including bowel inflammation, abdominal pain, constipation, and/or diarrhea [2]. They often also show unusual food-related behaviors, such as being extremely picky eaters. But his curiosity was especially piqued by evidence that certain gut microbes can influence abnormal behaviors in mice that model autism.

With his New Innovator Award, Bohórquez will study neuropods and the gut-brain connection in a mouse model of autism. Using the tools of optogenetics, which make it possible to activate cells with light, he’ll also see whether autism-like symptoms in mice can be altered or alleviated by controlling neuropods in the gut. Those symptoms include anxiety, repetitive behaviors, and lack of interest in interacting with other mice. He’ll also explore changes in the animals’ eating habits.

In another line of study, he will take advantage of intestinal tissue samples collected from people with autism. He’ll use those tissues to grow and then examine miniature intestinal “organoids,” looking for possible evidence that those from people with autism are different from others.

For the millions of people now living with autism, no truly effective drug therapies are available to help to manage the condition and its many behavioral and bodily symptoms. Bohórquez hopes one day to change that with drugs that act safely on the gut. In the meantime, he and his fellow “GASTRONAUTS” look forward to making some important and fascinating discoveries in the relatively uncharted territory where the gut meets the brain.

References:

[1] A gut-brain neural circuit for nutrient sensory transduction. Kaelberer MM, Buchanan KL, Klein ME, Barth BB, Montoya MM, Shen X, Bohórquez DV. Science. 2018 Sep 21;361(6408).

[2] Association of maternal report of infant and toddler gastrointestinal symptoms with autism: evidence from a prospective birth cohort. Bresnahan M, Hornig M, Schultz AF, Gunnes N, Hirtz D, Lie KK, Magnus P, Reichborn-Kjennerud T, Roth C, Schjølberg S, Stoltenberg C, Surén P, Susser E, Lipkin WI. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015 May;72(5):466-474.

Links:

Autism Spectrum Disorder (National Institute of Mental Health/NIH)

Bohórquez Lab (Duke University, Durham, NC)

Bohórquez Project Information (NIH RePORTER)

NIH Director’s New Innovator Award (Common Fund)

NIH Support: Common Fund; National Institute of Mental Health

Study Shows Genes Unique to Humans Tied to Bigger Brains

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

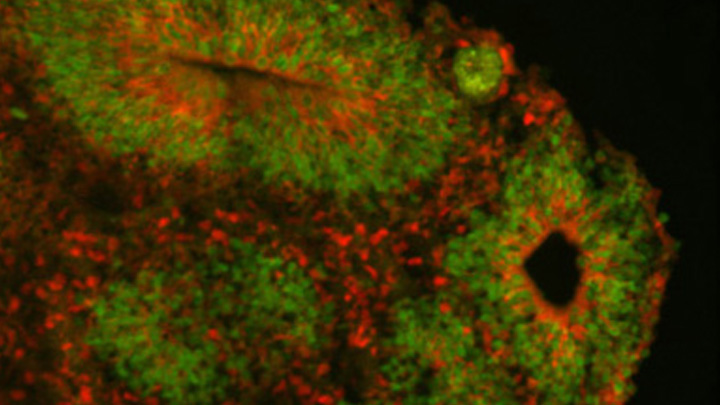

Caption: Cortical organoid, showing radial glial stem cells (green) and cortical neurons (red).

Credit: Sofie Salama, University of California, Santa Cruz

In seeking the biological answer to the question of what it means to be human, the brain’s cerebral cortex is a good place to start. This densely folded, outer layer of grey matter, which is vastly larger in Homo sapiens than in other primates, plays an essential role in human consciousness, language, and reasoning.

Now, an NIH-funded team has pinpointed a key set of genes—found only in humans—that may help explain why our species possesses such a large cerebral cortex. Experimental evidence shows these genes prolong the development of stem cells that generate neurons in the cerebral cortex, which in turn enables the human brain to produce more mature cortical neurons and, thus, build a bigger cerebral cortex than our fellow primates.

That sounds like a great advantage for humans! But there’s a downside. Researchers found the same genomic changes that facilitated the expansion of the human cortex may also render our species more susceptible to certain rare neurodevelopmental disorders.

Wearable Scanner Tracks Brain Activity While Body Moves

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Credit: Wellcome Centre for Human Neuroimaging, University College London.

In recent years, researchers fueled by the BRAIN Initiative and many other NIH-supported efforts have made remarkable progress in mapping the human brain in all its amazing complexity. Now, a powerful new imaging technology promises to further transform our understanding [1]. This wearable scanner, for the first time, enables researchers to track neural activity in people in real-time as they do ordinary things—be it drinking tea, typing on a keyboard, talking to a friend, or even playing paddle ball.

This new so-called magnetoencephalography (MEG) brain scanner, which looks like a futuristic cross between a helmet and a hockey mask, is equipped with specialized “quantum” sensors. When placed directly on the scalp surface, these new MEG scanners can detect weak magnetic fields generated by electrical activity in the brain. While current brain scanners weigh in at nearly 1,000 pounds and require people to come to a special facility and remain absolutely still, the new system weighs less than 2 pounds and is capable of generating 3D images even when a person is making motions.

Studies of Dogs, Mice, and People Provide Clues to OCD

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Thinkstock/wildpixel

Chances are you know someone with obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD). It’s estimated that more than 2 million Americans struggle with this mental health condition, characterized by unwanted recurring thoughts and/or repetitive behaviors, such as excessive hand washing or constant counting of objects. While we know that OCD tends to run in families, it’s been frustratingly difficult to identify specific genes that influence OCD risk.

Now, an international research team, partly funded by NIH, has made progress thanks to an innovative genomic approach involving dogs, mice, and people. The strategy allowed them to uncover four genes involved in OCD that turn out to play a role in synapses, where nerve impulses are transmitted between neurons in the brain. While more research is needed to confirm the findings and better understand the molecular mechanisms of OCD, these findings offer important new leads that could point the way to more effective treatments.

Autism Spectrum Disorder: Progress Toward Earlier Diagnosis

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Stockbyte

Research shows that the roots of autism spectrum disorder (ASD) generally start early—most likely in the womb. That’s one more reason, on top of a large number of epidemiological studies, why current claims about the role of vaccines in causing autism can’t be right. But how early is ASD detectable? It’s a critical question, since early intervention has been shown to help limit the effects of autism. The problem is there’s currently no reliable way to detect ASD until around 18–24 months, when the social deficits and repetitive behaviors associated with the condition begin to appear.

Several months ago, an NIH-funded team offered promising evidence that it may be possible to detect ASD in high-risk 1-year-olds by shifting attention from how kids act to how their brains have grown [1]. Now, new evidence from that same team suggests that neurological signs of ASD might be detectable even earlier.

Next Page