gastrointestinal tract

The Hidden Beauty of Intestinal Villi

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

The human small intestine, though modest in diameter and folded compactly to fit into the abdomen, is anything but small. It measures on average about 20 feet from end to end and plays a big role in the gastrointestinal tract, breaking down food and drink from the stomach to absorb the water and nutrients.

Also anything but small is the total surface area of the organ’s inner lining, where millions of U-shaped folds in the mucosal tissue triple the available space to absorb the water and nutrients that keep our bodies nourished. If these folds, packed with finger-like absorptive cells called villi, were flattened out, they would be the size of a tennis court!

That’s what makes this this microscopic image so interesting. It shows in cross section the symmetrical pattern of the villi (its cells outlined by yellow) that pack these folds. Each cell’s nucleus contains DNA (teal), and the villi themselves are fringed by thousands of tiny bristles, called microvilli (magenta), which are too small to see individually here. Collectively, microvilli make up an absorptive surface, called the brush border, where digested nutrients in the fluid passing through the intestine can enter cells via transport channels.

Amy Engevik, a researcher at the Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, took this snapshot to show what a healthy intestinal cellular landscape looks like in a young mouse. The Engevik lab studies the dynamic movement of ions, water, and proteins in the intestine—a process that goes wrong in humans born with a rare disorder called microvillus inclusion disease (MVID).

MVID causes chronic gastrointestinal problems in newborn babies, due to defects in a protein that transports various cellular components. Because they cannot properly absorb nutrition from food, these tiny patients require intravenous feeding almost immediately, which carries a high risk for sepsis and intestinal injury.

Engevik and her team study this disease using a mouse model that replicates many of the characteristics of the disorder in humans [1]. Interestingly, when Engevik gets together with her family, she isn’t the only one talking about MVID and villi. Her two sisters, Mindy and Kristen, also study the basic science of gastrointestinal disorders! Instead of sibling rivalry, though, this close alliance has strengthened the quality of her research, says Amy, who is the middle child.

Beyond advancing science and nurturing sisterhood in science, Engevik’s work also captured the fancy of the judges for the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology’s annual BioArt Scientific Image and Video Competition. Her image was one of 10 winners announced in December 2020.

Because multiple models are useful for understanding fundamentals of diseases like MVID, Engevik has also developed a large-animal model (pig) that has many features of the human disease [2]. She hopes that her efforts will help to improve our understanding of MVID and other digestive diseases, as well as lead to new, potentially life-saving treatments for babies suffering from MVID.

References:

[1] Loss of MYO5B Leads to reductions in Na+ absorption with maintenance of CFTR-dependent Cl- secretion in enterocytes. Engevik AC, Kaji I, Engevik MA, Meyer AR, Weis VG, Goldstein A, Hess MW, Müller T, Koepsell H, Dudeja PK, Tyska M, Huber LA, Shub MD, Ameen N, Goldenring JR. Gastroenterology. 2018 Dec;155(6):1883-1897.e10.

[2] Editing myosin VB gene to create porcine model of microvillus inclusion disease, with microvillus-lined inclusions and alterations in sodium transporters. Engevik AC, Coutts AW, Kaji I, Rodriguez P, Ongaratto F, Saqui-Salces M, Medida RL, Meyer AR, Kolobova E, Engevik MA, Williams JA, Shub MD, Carlson DF, Melkamu T, Goldenring JR. Gastroenterology. 2020 Jun;158(8):2236-2249.e9.

Links:

Microvillus inclusion disease (Genetic and Rare Diseases Center/NIH)

Digestive Diseases (National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases/NIH)

Amy Engevik (Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston)

Podcast: A Tale of Three Sisters featuring Drs. Mindy, Amy, and Kristen Engevik (The Immunology Podcast, April 29, 2021)

BioArt Scientific Image and Video Competition (Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology, Bethesda, MD)

NIH Support: National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases

Could A Gut-Brain Connection Help Explain Autism?

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

You might think nutrient-sensing cells in the human gastrointestinal (GI) tract would have no connection whatsoever to autism spectrum disorder (ASD). But if Diego Bohórquez’s “big idea” is correct, these GI cells, called neuropods, could one day help to provide a direct link into understanding and treating some aspects of autism and other brain disorders.

Bohórquez, a researcher at Duke University, Durham, NC, recently discovered that cells in the intestine, previously known for their hormone-releasing ability, form extensions similar to neurons. He also found that those extensions connect to nerve fibers in the gut, which relay signals to the vagus nerve and onward to the brain. In fact, he found that those signals reach the brain in milliseconds [1].

Bohórquez has dedicated his lab to studying this direct, high-speed hookup between gut and brain and its impact on nutrient sensing, eating, and other essential behaviors. Now, with support from a 2019 NIH Director’s New Innovator Award, he will also explore the potential for treating autism and other brain disorders with drugs that act on the gut.

Bohórquez became interested in autism and its possible link to the gut-brain connection after a chance encounter with Geraldine Dawson, director of the Duke Center for Autism and Brain Development. Dawson mentioned that autism typically affects multiple organ systems.

With further reading, he discovered that kids with autism frequently cope with GI issues, including bowel inflammation, abdominal pain, constipation, and/or diarrhea [2]. They often also show unusual food-related behaviors, such as being extremely picky eaters. But his curiosity was especially piqued by evidence that certain gut microbes can influence abnormal behaviors in mice that model autism.

With his New Innovator Award, Bohórquez will study neuropods and the gut-brain connection in a mouse model of autism. Using the tools of optogenetics, which make it possible to activate cells with light, he’ll also see whether autism-like symptoms in mice can be altered or alleviated by controlling neuropods in the gut. Those symptoms include anxiety, repetitive behaviors, and lack of interest in interacting with other mice. He’ll also explore changes in the animals’ eating habits.

In another line of study, he will take advantage of intestinal tissue samples collected from people with autism. He’ll use those tissues to grow and then examine miniature intestinal “organoids,” looking for possible evidence that those from people with autism are different from others.

For the millions of people now living with autism, no truly effective drug therapies are available to help to manage the condition and its many behavioral and bodily symptoms. Bohórquez hopes one day to change that with drugs that act safely on the gut. In the meantime, he and his fellow “GASTRONAUTS” look forward to making some important and fascinating discoveries in the relatively uncharted territory where the gut meets the brain.

References:

[1] A gut-brain neural circuit for nutrient sensory transduction. Kaelberer MM, Buchanan KL, Klein ME, Barth BB, Montoya MM, Shen X, Bohórquez DV. Science. 2018 Sep 21;361(6408).

[2] Association of maternal report of infant and toddler gastrointestinal symptoms with autism: evidence from a prospective birth cohort. Bresnahan M, Hornig M, Schultz AF, Gunnes N, Hirtz D, Lie KK, Magnus P, Reichborn-Kjennerud T, Roth C, Schjølberg S, Stoltenberg C, Surén P, Susser E, Lipkin WI. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015 May;72(5):466-474.

Links:

Autism Spectrum Disorder (National Institute of Mental Health/NIH)

Bohórquez Lab (Duke University, Durham, NC)

Bohórquez Project Information (NIH RePORTER)

NIH Director’s New Innovator Award (Common Fund)

NIH Support: Common Fund; National Institute of Mental Health

How Mucus Tames Microbes

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Most of us think of mucus as little more than slimy and somewhat yucky stuff that’s easily ignored until you come down with a cold like the one I just had. But, when it comes to our health, there’s much more to mucus than you might think.

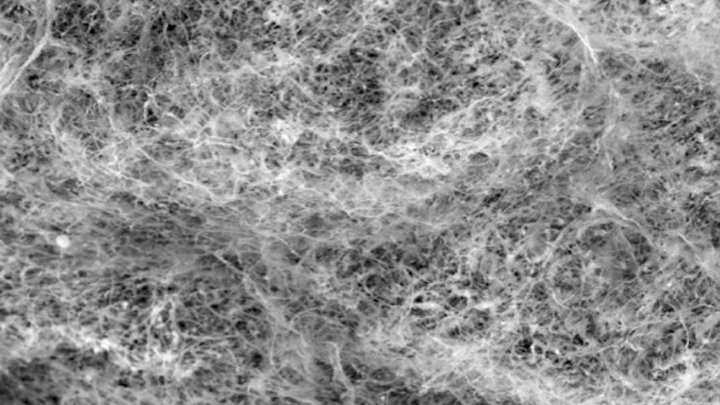

Mucus covers the moist surfaces of the human body, including the eyes, nostrils, lungs, and gastrointestinal tract. In fact, the average person makes more than a liter of mucus each day! It houses trillions of microbes and serves as a first line of defense against the subset of those microorganisms that cause infections. For these reasons, NIH-funded researchers, led by Katharina Ribbeck, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, are out to gain a greater understanding of the biology of healthy mucus—and then possibly use that knowledge to develop new therapeutics.

Ribbeck’s team used a scanning electron microscope to take the image of mucus you see above. You’ll notice right away that mucus doesn’t look like simple slime at all. In fact, if you could zoom into this complex web, you’d discover it’s made up of mucin proteins and glycans, which are sugar molecules that resemble bottle brushes.

Ribbeck and her colleagues recently discovered that the glycans in healthy mucus play a long-overlooked role in “taming” bacteria that might make us ill [1]. This work builds on their previous findings that mucus interferes with bacterial behavior, preventing these bugs from attaching to surfaces and communicating with each other [2].

In their new study, published in Nature Microbiology, Ribbeck, lead author Kelsey Wheeler, and their colleagues studied mucus and its interactions with Pseudomonas aeruginosa. This bacterium is a common cause of serious lung infections in people with cystic fibrosis or compromised immune systems.

The researchers found that in the presence of glycans, P. aeruginosa was rendered less harmful and infectious. The bacteria also produced fewer toxins. The findings show that it isn’t just that microbes get trapped in a tangled web within mucus, but rather that glycans have a special ability to moderate the bugs’ behavior. The researchers also have evidence of similar interactions between mucus and other microorganisms, such as those responsible for yeast infections.

The new study highlights an intriguing strategy to tame, rather than kill, bacteria to manage infections. In fact, Ribbeck views mucus and its glycans as a therapeutic gold mine. She hopes to apply what she’s learned to develop artificial mucus as an anti-microbial therapeutic for use inside and outside the body. Not bad for a substance that you might have thought was nothing more than slimy stuff.

References:

[1] Mucin glycans attenuate the virulence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in infection. Wheeler KM, Cárcamo-Oyarce G, Turner BS, Dellos-Nolan S, Co JY, Lehoux S, Cummings RD, Wozniak DJ, Ribbeck K. Nat Microbiol. 2019 Oct 14.

[2] Mucins trigger dispersal of Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms. Co JY, Cárcamo-Oyarce, Billings N, Wheeler KM, Grindy SC, Holten-Andersen N, Ribbeck K. NPJ Biofilms Microbiomes. 2018 Oct 10;4:23.

Links:

Cystic Fibrosis (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute/NIH)

Video: Chemistry in Action—Katharina Ribbeck (YouTube)

Katharina Ribbeck (Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge)

NIH Support: National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering; National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences; National Institute of General Medical Sciences; National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases

Creative Minds: Giving Bacteria Needles to Fight Intestinal Disease

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

For Salmonella and many other disease-causing bacteria that find their way into our bodies, infection begins with a poke. That’s because these bad bugs are equipped with a needle-like protein filament that punctures the outer membrane of human cells and then, like a syringe, injects dozens of toxic proteins that help them replicate.

Cammie Lesser at Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Cambridge, and her colleagues are now on a mission to bioengineer strains of bacteria that don’t cause disease to make these same syringes, called type III secretion systems. The goal is to use such “good” bacteria to deliver therapeutic molecules, rather than toxins, to human cells. Their first target is the gastrointestinal tract, where they hope to knock out hard-to-beat bacterial infections or to relieve the chronic inflammation that comes with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).

Creative Minds: The Human Gut Microbiome’s Top 100 Hits

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Michael Fishbach

Microbes that live in dirt often engage in their own deadly turf wars, producing a toxic mix of chemical compounds (also called “small molecules”) that can be a source of new antibiotics. When he started out in science more than a decade ago, Michael Fischbach studied these soil-dwelling microbes to look for genes involved in making these compounds.

Eventually, Fischbach, who is now at the University of California, San Francisco, came to a career-altering realization: maybe he didn’t need to dig in dirt! He hypothesized an even better way to improve human health might be found in the genes of the trillions of microorganisms that dwell in and on our bodies, known collectively as the human microbiome.

Creative Minds: Making a Miniature Colon in the Lab

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Caption: Top down view of gut tissue monolayer grown on an engineered scaffold, which guides the cells into organized crypts structures similar to the conformation of crypts in the human colon. Areas between the circles represent the flat lumenal surface.

Credit: Nancy Allbritton, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill

When Nancy Allbritton was a child in Marksville, LA, she designed and built her own rabbit hutches. She also once took apart an old TV set to investigate the cathode ray tube inside before turning the wooden frame that housed the TV into a bookcase, which, by the way, she still has. Allbritton’s natural curiosity for how things work later inspired her to earn advanced degrees in medicine, medical engineering, and medical physics, while also honing her skills in cell biology and analytical chemistry.

Now, Allbritton applies her wide-ranging research background to design cutting-edge technologies in her lab at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill. In one of her boldest challenges yet, supported by a 2015 NIH Director’s Transformative Research Award, Allbritton and a multidisciplinary team of collaborators have set out to engineer a functional model of a large intestine, or colon, on a microfabricated chip about the size of a dime.

Nanojuice: Getting a Real-Time View of GI Motility

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

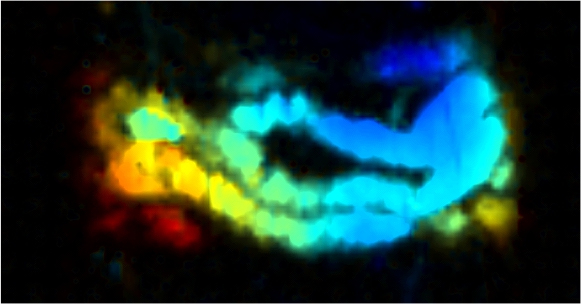

Caption: A real-time image of nanojuice as it passes through a mouse’s small intestine. A laser causes particles in the nanojuice to vibrate, creating vibrations picked up by an ultrasound detector that are then used to generate a black-and-white image. Rainbow colors are added afterward to reflect the depth of the intestine within the mouse’s abdomen: blue is closest to the surface and red is deepest.

Credit: Jonathan Lovell, University at Buffalo

For those of you who love to try new juices, you’ve probably checked out acai, goji berry, and maybe even cold-pressed kale. But have you heard of nanojuice? While it’s not a new kind of health food, this scientific invention may someday help to improve human health through its power to visualize the action of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract in real-time.

It’s true that doctors already have many imaging tools at their disposal to examine various parts of the GI tract—all the way from throat to colon. These include invasive techniques, such as upper endoscopy and colonoscopy; as well as non-invasive approaches, such as ultrasound, magnetic resonance imaging, and X-ray procedures that may or may not involve swallowing a chalky liquid containing barium or other materials that are radio-opaque. There’s even a wireless capsule that can shoot videos as it travels all the way through the GI tract. None of these techniques, however, provides a non-invasive, real-time view of the wave-like muscle contractions that move food through the gut—a crucial process called peristalsis.