drug resistance

Caught on Video: Cancer Cells in Act of Cannibalism

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Tumors rely on a variety of tricks to grow, spread, and resist our best attempts to destroy them. Now comes word of yet another of cancer’s surprising stunts: when chemotherapy treatment hits hard, some cancer cells survive by cannibalizing other cancer cells.

Researchers recently caught this ghoulish behavior on video. In what, during this Halloween season, might look a little bit like The Blob, you can see a down-for-the-count breast cancer cell (green), treated earlier with the chemotherapy drug doxorubicin, gobbling up a neighboring cancer cell (red). The surviving cell delivers its meal to internal compartments called lysosomes, which digest it in a last-ditch effort to get some nourishment and keep going despite what should have been a lethal dose of a cancer drug.

Crystal Tonnessen-Murray, a postdoctoral researcher in the lab of James Jackson, Tulane University School of Medicine, New Orleans, captured these dramatic interactions using time-lapse and confocal microscopy. When Tonnessen-Murray saw the action, she almost couldn’t believe her eyes. Tumor cells eating tumor cells wasn’t something that she’d learned about in school.

As the NIH-funded team described in the Journal of Cell Biology, these chemotherapy-treated breast cancer cells were not only cannibalizing their neighbors, they were doing it with remarkable frequency [1]. But why?

A possible explanation is that some cancer cells resist chemotherapy by going dormant and not dividing. The new study suggests that while in this dormant state, cannibalism is one way that tumor cells can keep going.

The study also found that these acts of cancer cell cannibalism depend on genetic programs closely resembling those of immune cells called macrophages. These scavenging cells perform their important protective roles by gobbling up invading bacteria, viruses, and other infectious microbes. Drug-resistant breast cancer cells have apparently co-opted similar programs in response to chemotherapy but, in this case, to eat their own neighbors.

Tonnessen-Murray’s team confirmed that cannibalizing cancer cells have a survival advantage. The findings suggest that treatments designed to block the cells’ cannibalistic tendencies might hold promise as a new way to treat otherwise hard-to-treat cancers. That’s a possibility the researchers are now exploring, although they report that stopping the cells from this dramatic survival act remains difficult.

Reference:

[1] Chemotherapy-induced senescent cancer cells engulf other cells to enhance their survival. Tonnessen-Murray CA, Frey WD, Rao SG, Shahbandi A, Ungerleider NA, Olayiwola JO, Murray LB, Vinson BT, Chrisey DB, Lord CJ, Jackson JG. J Cell Biol. 2019 Sep 17.

Links:

Breast Cancer (National Cancer Institute/NIH)

James Jackson (Tulane University School of Medicine, New Orleans)

NIH Support: National Institute of General Medical Sciences

Tagging Essential Malaria Genes to Advance Drug Development

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

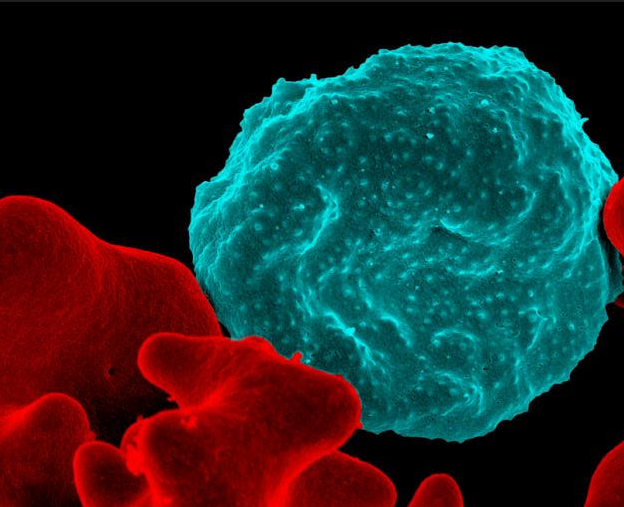

Caption: Colorized scanning electron micrograph of a blood cell infected with malaria parasites (blue with dots) surrounded by uninfected cells (red).

Credit: National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, NIH

As a volunteer physician in a small hospital in Nigeria 30 years ago, I was bitten by lots of mosquitoes and soon came down with headache, chills, fever, and muscle aches. It was malaria. Fortunately, the drug available to me then was effective, but I was pretty sick for a few days. Since that time, malarial drug resistance has become steadily more widespread. In fact, the treatment that cured me would be of little use today. Combination drug therapies including artemisinin have been introduced to take the place of the older drugs [1], but experts are concerned the mosquito-borne parasites that cause malaria are showing signs of drug resistance again.

So, researchers have been searching the genome of Plasmodium falciparum, the most-lethal species of the malaria parasite, for potentially better targets for drug or vaccine development. You wouldn’t think such work would be too tough because the genome of P. falciparum was sequenced more than 15 years ago [2]. Yet it’s proven to be a major challenge because the genetic blueprint of this protozoan parasite has an unusual bias towards two nucleotides (adenine and thymine), which makes it difficult to use standard research tools to study the functions of its genes.

Now, using a creative new spin on an old technique, an NIH-funded research team has solved this difficult problem and, for the first time, completely characterized the genes in the P. falciparum genome [3]. Their work identified 2,680 genes essential to P. falciparum’s growth and survival in red blood cells, where it does the most damage in humans. This gene list will serve as an important guide in the years ahead as researchers seek to identify the equivalent of a malarial Achilles heel, and use that to develop new and better ways to fight this deadly tropical disease.

Creative Minds: Rapid Testing for Antibiotic Resistance

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Ahmad (Mo) Khalil

The term “freeze-dried” may bring to mind those handy MREs (Meals Ready to Eat) consumed by legions of soldiers, astronauts, and outdoor adventurers. But if one young innovator has his way, a test that features freeze-dried biosensors may soon be a key ally in our nation’s ongoing campaign against the very serious threat of antibiotic-resistant bacterial infections.

Each year, antibiotic-resistant infections account for more than 23,000 deaths in the United States. To help tackle this challenge, Ahmad (Mo) Khalil, a researcher at Boston University, recently received an NIH Director’s New Innovator Award to develop a system that can more quickly determine whether a patient’s bacterial infection will respond best to antibiotic X or antibiotic Y—or, if the infection is actually viral rather than bacterial, no antibiotics are needed at all.

Creative Minds: Applying CRISPR Technology to Cancer Drug Resistance

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Patrick Hsu

As a child, Patrick Hsu once settled a disagreement with his mother over antibacterial wipes by testing them in controlled experiments in the kitchen. When the family moved to Palo Alto, CA, instead of trying out for the football team or asking to borrow the family car like other high school kids might have done, Hsu went knocking on doors of scientists at Stanford University. He found his way into a neuroscience lab, where he gained experience with the fundamental tools of biology and a fascination for understanding how the brain works. But Hsu would soon become impatient with the tools that were available to ask some of the big questions he wanted to study.

As a Salk Helmsley Fellow and principal investigator at the Salk Institute for Biological Studies, La Jolla, CA, Hsu now works at the intersection of bioengineering, genomics, and neuroscience with a DNA editing tool called CRISPR/Cas9 that is revolutionizing the way scientists can ask and answer those big questions. (This blog has previously featured several examples of how this technology is revolutionizing biomedical research.) Hsu has received a 2015 NIH Director’s Early Independence award to adapt CRISPR/Cas9 technology so its use can be extended to that other critically important information-containing nucleic acid—RNA.Specifically, Hsu aims to develop ways to use this new tool to examine the role of a certain type of RNA in cancer drug resistance.

LabTV: Curious About Drug Resistance of Hepatitis C Virus

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

As long as she can remember, Ashley Matthew wanted to be a medical doctor. She took every opportunity to pursue her dream, including shadowing physicians to learn more about what a career in health care is really like. But, as Matthew explains in today’s LabTV video, she also became attracted to the idea of doing research because of her affinity for solving problems and “figuring things out.”

So, Matthew decided to give biomedical research a try, landing a spot in an undergraduate summer program sponsored by the University of Massachusetts. Ten weeks later, she was convinced that her future in medicine just had to include a research component. That’s why Matthew is now well on her way as an M.D./Ph.D. student at the University of Massachusetts Medical School, Worcester, where she works in the lab of Celia Schiffer.

Knocking Out Melanoma: Does This Triple Combo Have What It Takes?

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

It would be great if we could knock out cancer with a single punch. But the more we learn about cancer’s molecular complexities and the immune system’s response to tumors, the more it appears that we may need a precise combination of blows to defeat a patient’s cancer permanently, with no need for a later rematch. One cancer that provides us with a ringside seat on the powerful potential—and tough challenges—of targeted combination therapy is melanoma, especially the approximately 50% of advanced tumors with a specific “driver” mutation in the BRAF gene [1].

Drugs that target cells carrying BRAF mutations initially provided great hope for melanoma, with many reports of dramatic shrinkage of tumors in patients with advanced disease. But almost invariably, the disease recurred and was no longer responsive to those same drugs. A few years ago, researchers thought they’d come up with a solid combination to fight BRAF-mutant melanoma: a one-two punch that paired a BRAF-inhibiting drug with an agent that sensitized the immune system [2]. However, when that combo was tested in humans, the clinical trial had to be stopped early because of serious liver toxicity [3]. Now, in a mouse study published in Science Translational Medicine, NIH-funded researchers at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) provide renewed hope for a safe, effective combination therapy for melanoma—with a strategy that adds a third drug to the mix [4].