skin cancer

Immune Resilience is Key to a Long and Healthy Life

Posted on by Lawrence Tabak, D.D.S., Ph.D.

Do you feel as if you or perhaps your family members are constantly coming down with illnesses that drag on longer than they should? Or, maybe you’re one of those lucky people who rarely becomes ill and, if you do, recovers faster than others.

It’s clear that some people generally are more susceptible to infectious illnesses, while others manage to stay healthier or bounce back more quickly, sometimes even into old age. Why is this? A new study from an NIH-supported team has an intriguing answer [1]. The difference, they suggest, may be explained in part by a new measure of immunity they call immune resilience—the ability of the immune system to rapidly launch attacks that defend effectively against infectious invaders and respond appropriately to other types of inflammatory stressors, including aging or other health conditions, and then quickly recover, while keeping potentially damaging inflammation under wraps.

The findings in the journal Nature Communications come from an international team led by Sunil Ahuja, University of Texas Health Science Center and the Department of Veterans Affairs Center for Personalized Medicine, both in San Antonio. To understand the role of immune resilience and its effect on longevity and health outcomes, the researchers looked at multiple other studies including healthy individuals and those with a range of health conditions that challenged their immune systems.

By looking at multiple studies in varied infectious and other contexts, they hoped to find clues as to why some people remain healthier even in the face of varied inflammatory stressors, ranging from mild to more severe. But to understand how immune resilience influences health outcomes, they first needed a way to measure or grade this immune attribute.

The researchers developed two methods for measuring immune resilience. The first metric, a laboratory test called immune health grades (IHGs), is a four-tier grading system that calculates the balance between infection-fighting CD8+ and CD4+ T-cells. IHG-I denotes the best balance tracking the highest level of resilience, and IHG-IV denotes the worst balance tracking the lowest level of immune resilience. An imbalance between the levels of these T cell types is observed in many people as they age, when they get sick, and in people with autoimmune diseases and other conditions.

The researchers also developed a second metric that looks for two patterns of expression of a select set of genes. One pattern associated with survival and the other with death. The survival-associated pattern is primarily related to immune competence, or the immune system’s ability to function swiftly and restore activities that encourage disease resistance. The mortality-associated genes are closely related to inflammation, a process through which the immune system eliminates pathogens and begins the healing process but that also underlies many disease states.

Their studies have shown that high expression of the survival-associated genes and lower expression of mortality-associated genes indicate optimal immune resilience, correlating with a longer lifespan. The opposite pattern indicates poor resilience and a greater risk of premature death. When both sets of genes are either low or high at the same time, immune resilience and mortality risks are more moderate.

In the newly reported study initiated in 2014, Ahuja and his colleagues set out to assess immune resilience in a collection of about 48,500 people, with or without various acute, repetitive, or chronic challenges to their immune systems. In an earlier study, the researchers showed that this novel way to measure immune status and resilience predicted hospitalization and mortality during acute COVID-19 across a wide age spectrum [2].

The investigators have analyzed stored blood samples and publicly available data representing people, many of whom were healthy volunteers, who had enrolled in different studies conducted in Africa, Europe, and North America. Volunteers ranged in age from 9 to 103 years. They also evaluated participants in the Framingham Heart Study, a long-term effort to identify common factors and characteristics that contribute to cardiovascular disease.

To examine people with a wide range of health challenges and associated stresses on their immune systems, the team also included participants who had influenza or COVID-19, and people living with HIV. They also included kidney transplant recipients, people with lifestyle factors that put them at high risk for sexually transmitted infections, and people who’d had sepsis, a condition in which the body has an extreme and life-threatening response following an infection.

The question in all these contexts was the same: How well did the two metrics of immune resilience predict an individual’s health outcomes and lifespan? The short answer is that immune resilience, longevity, and better health outcomes tracked together well. Those with metrics indicating optimal immune resilience generally had better health outcomes and lived longer than those who had lower scores on the immunity grading scale. Indeed, those with optimal immune resilience were more likely to:

- Live longer,

- Resist HIV infection or the progression from HIV to AIDS,

- Resist symptomatic influenza,

- Resist a recurrence of skin cancer after a kidney transplant,

- Survive COVID-19, and

- Survive sepsis.

The study also revealed other interesting findings. While immune resilience generally declines with age, some people maintain higher levels of immune resilience as they get older for reasons that aren’t yet known, according to the researchers. Some people also maintain higher levels of immune resilience despite the presence of inflammatory stress to their immune systems such as during HIV infection or acute COVID-19. People of all ages can show high or low immune resilience. The study also found that higher immune resilience is more common in females than it is in males.

The findings suggest that there is a lot more to learn about why people differ in their ability to preserve optimal immune resilience. With further research, it may be possible to develop treatments or other methods to encourage or restore immune resilience as a way of improving general health, according to the study team.

The researchers suggest it’s possible that one day checkups of a person’s immune resilience could help us to understand and predict an individual’s health status and risk for a wide range of health conditions. It could also help to identify those individuals who may be at a higher risk of poor outcomes when they do get sick and may need more aggressive treatment. Researchers may also consider immune resilience when designing vaccine clinical trials.

A more thorough understanding of immune resilience and discovery of ways to improve it may help to address important health disparities linked to differences in race, ethnicity, geography, and other factors. We know that healthy eating, exercising, and taking precautions to avoid getting sick foster good health and longevity; in the future, perhaps we’ll also consider how our immune resilience measures up and take steps to achieve or maintain a healthier, more balanced, immunity status.

References:

[1] Immune resilience despite inflammatory stress promotes longevity and favorable health outcomes including resistance to infection. Ahuja SK, Manoharan MS, Lee GC, McKinnon LR, Meunier JA, Steri M, Harper N, Fiorillo E, Smith AM, Restrepo MI, Branum AP, Bottomley MJ, Orrù V, Jimenez F, Carrillo A, Pandranki L, Winter CA, Winter LA, Gaitan AA, Moreira AG, Walter EA, Silvestri G, King CL, Zheng YT, Zheng HY, Kimani J, Blake Ball T, Plummer FA, Fowke KR, Harden PN, Wood KJ, Ferris MT, Lund JM, Heise MT, Garrett N, Canady KR, Abdool Karim SS, Little SJ, Gianella S, Smith DM, Letendre S, Richman DD, Cucca F, Trinh H, Sanchez-Reilly S, Hecht JM, Cadena Zuluaga JA, Anzueto A, Pugh JA; South Texas Veterans Health Care System COVID-19 team; Agan BK, Root-Bernstein R, Clark RA, Okulicz JF, He W. Nat Commun. 2023 Jun 13;14(1):3286. doi: 10.1038/s41467-023-38238-6. PMID: 37311745.

[2] Immunologic resilience and COVID-19 survival advantage. Lee GC, Restrepo MI, Harper N, Manoharan MS, Smith AM, Meunier JA, Sanchez-Reilly S, Ehsan A, Branum AP, Winter C, Winter L, Jimenez F, Pandranki L, Carrillo A, Perez GL, Anzueto A, Trinh H, Lee M, Hecht JM, Martinez-Vargas C, Sehgal RT, Cadena J, Walter EA, Oakman K, Benavides R, Pugh JA; South Texas Veterans Health Care System COVID-19 Team; Letendre S, Steri M, Orrù V, Fiorillo E, Cucca F, Moreira AG, Zhang N, Leadbetter E, Agan BK, Richman DD, He W, Clark RA, Okulicz JF, Ahuja SK. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2021 Nov;148(5):1176-1191. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2021.08.021. Epub 2021 Sep 8. PMID: 34508765; PMCID: PMC8425719.

Links:

COVID-19 Research (NIH)

HIV Info (NIH)

Sepsis (National Institute of General Medical Sciences/NIH)

Sunil Ahuja (University of Texas Health Science Center, San Antonio)

Framingham Heart Study (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute/NIH)

“A Secret to Health and Long Life? Immune Resilience, NIAID Grantees Report,” NIAID Now Blog, June 13, 2023

NIH Support: National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases; National Institute on Aging; National Institute of Mental Health; National Institute of General Medical Sciences; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute

A Global Look at Cancer Genomes

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Cancer is a disease of the genome. It can be driven by many different types of DNA misspellings and rearrangements, which can cause cells to grow uncontrollably. While the first oncogenes with the potential to cause cancer were discovered more than 35 years ago, it’s been a long slog to catalog the universe of these potential DNA contributors to malignancy, let alone explore how they might inform diagnosis and treatment. So, I’m thrilled that an international team has completed the most comprehensive study to date of the entire genomes—the complete sets of DNA—of 38 different types of cancer.

Among the team’s most important discoveries is that the vast majority of tumors—about 95 percent—contained at least one identifiable spelling change in their genomes that appeared to drive the cancer [1]. That’s significantly higher than the level of “driver mutations” found in past studies that analyzed only a tumor’s exome, the small fraction of the genome that codes for proteins. Because many cancer drugs are designed to target specific proteins affected by driver mutations, the new findings indicate it may be worthwhile, perhaps even life-saving in many cases, to sequence the entire tumor genomes of a great many more people with cancer.

The latest findings, detailed in an impressive collection of 23 papers published in Nature and its affiliated journals, come from the international Pan-Cancer Analysis of Whole Genomes (PCAWG) Consortium. Also known as the Pan-Cancer Project for short, it builds on earlier efforts to characterize the genomes of many cancer types, including NIH’s The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) and the International Cancer Genome Consortium (ICGC).

In these latest studies, a team including more than 1,300 researchers from around the world analyzed the complete genomes of more than 2,600 cancer samples. Those samples included tumors of the brain, skin, esophagus, liver, and more, along with matched healthy cells taken from the same individuals.

In each of the resulting new studies, teams of researchers dug deep into various aspects of the cancer DNA findings to make a series of important inferences and discoveries. Here are a few intriguing highlights:

• The average cancer genome was found to contain not just one driver mutation, but four or five.

• About 13 percent of those driver mutations were found in so-called non-coding DNA, portions of the genome that don’t code for proteins [2].

• The mutations arose within about 100 different molecular processes, as indicated by their unique patterns or “mutational signatures.” [3,4].

• Some of those signatures are associated with known cancer causes, including aberrant DNA repair and exposure to known carcinogens, such as tobacco smoke or UV light. Interestingly, many others are as-yet unexplained, suggesting there’s more to learn with potentially important implications for cancer prevention and drug development.

• A comprehensive analysis of 47 million genetic changes pieced together the chronology of cancer-causing mutations. This work revealed that many driver mutations occur years, if not decades, prior to a cancer’s diagnosis, a discovery with potentially important implications for early cancer detection [5].

The findings represent a big step toward cataloging all the major cancer-causing mutations with important implications for the future of precision cancer care. And yet, the fact that the drivers in 5 percent of cancers continue to remain mysterious (though they do have RNA abnormalities) comes as a reminder that there’s still a lot more work to do. The challenging next steps include connecting the cancer genome data to treatments and building meaningful predictors of patient outcomes.

To help in these endeavors, the Pan-Cancer Project has made all of its data and analytic tools available to the research community. As researchers at NIH and around the world continue to detail the diverse genetic drivers of cancer and the molecular processes that contribute to them, there is hope that these findings and others will ultimately vanquish, or at least rein in, this Emperor of All Maladies.

References:

[1] Pan-Cancer analysis of whole genomes. ICGC/TCGA Pan-Cancer Analysis of Whole Genomes Consortium. Nature. 2020 Feb;578(7793):82-93.

[2] Analyses of non-coding somatic drivers in 2,658 cancer whole genomes. Rheinbay E et al; PCAWG Consortium. Nature. 2020 Feb;578(7793):102-111.

[3] The repertoire of mutational signatures in human cancer. Alexandrov LB et al; PCAWG Consortium. Nature. 2020 Feb;578(7793):94-101.

[4] Patterns of somatic structural variation in human cancer genomes. Li Y et al; PCAWG Consortium. Nature. 2020 Feb;578(7793):112-121.

[5] The evolutionary history of 2,658 cancers. Gerstung M, Jolly C, Leshchiner I, Dentro SC et al; PCAWG Consortium. Nature. 2020 Feb;578(7793):122-128.

Links:

The Genetics of Cancer (National Cancer Institute/NIH)

Precision Medicine in Cancer Treatment (NCI)

The Cancer Genome Atlas Program (NIH)

NCI and the Precision Medicine Initiative (NCI)

NIH Support: National Cancer Institute, National Human Genome Research Institute

Creative Minds: Applying CRISPR Technology to Cancer Drug Resistance

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Patrick Hsu

As a child, Patrick Hsu once settled a disagreement with his mother over antibacterial wipes by testing them in controlled experiments in the kitchen. When the family moved to Palo Alto, CA, instead of trying out for the football team or asking to borrow the family car like other high school kids might have done, Hsu went knocking on doors of scientists at Stanford University. He found his way into a neuroscience lab, where he gained experience with the fundamental tools of biology and a fascination for understanding how the brain works. But Hsu would soon become impatient with the tools that were available to ask some of the big questions he wanted to study.

As a Salk Helmsley Fellow and principal investigator at the Salk Institute for Biological Studies, La Jolla, CA, Hsu now works at the intersection of bioengineering, genomics, and neuroscience with a DNA editing tool called CRISPR/Cas9 that is revolutionizing the way scientists can ask and answer those big questions. (This blog has previously featured several examples of how this technology is revolutionizing biomedical research.) Hsu has received a 2015 NIH Director’s Early Independence award to adapt CRISPR/Cas9 technology so its use can be extended to that other critically important information-containing nucleic acid—RNA.Specifically, Hsu aims to develop ways to use this new tool to examine the role of a certain type of RNA in cancer drug resistance.

Precision Oncology: Creating a Genomic Guide for Melanoma Therapy

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Caption: Human malignant melanoma cell viewed through a fluorescent, laser-scanning confocal microscope. Invasive structures involved in metastasis appear as greenish-yellow dots, while actin (green) and vinculin (red) are components of the cell’s cytoskeleton.

Credit: Vira V. Artym, National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, NIH

It’s still the case in most medical care systems that cancers are classified mainly by the type of tissue or part of the body in which they arose—lung, brain, breast, colon, pancreas, and so on. But a radical change is underway. Thanks to advances in scientific knowledge and DNA sequencing technology, researchers are identifying the molecular fingerprints of various cancers and using them to divide cancer’s once-broad categories into far more precise types and subtypes. They are also discovering that cancers that arise in totally different parts of the body can sometimes have a lot in common. Not only can molecular analysis refine diagnosis and provide new insights into what’s driving the growth of a specific tumor, it may also point to the treatment strategy with the greatest chance of helping a particular patient.

The latest cancer to undergo such rigorous, comprehensive molecular analysis is malignant melanoma. While melanoma can rarely arise in the eye and a few other parts of the body, this report focused on the more familiar “cutaneous melanoma,” a deadly and increasingly common form of skin cancer [1]. Reporting in the journal Cell [2], The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) Network says it has identified four distinct molecular subtypes of melanoma. In addition, the NIH-funded network identified an immune signature that spans all four subtypes. Together, these achievements establish a much-needed framework that may guide decisions about which targeted drug, immunotherapy, or combination of therapies to try in an individual with melanoma.

Knocking Out Melanoma: Does This Triple Combo Have What It Takes?

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

It would be great if we could knock out cancer with a single punch. But the more we learn about cancer’s molecular complexities and the immune system’s response to tumors, the more it appears that we may need a precise combination of blows to defeat a patient’s cancer permanently, with no need for a later rematch. One cancer that provides us with a ringside seat on the powerful potential—and tough challenges—of targeted combination therapy is melanoma, especially the approximately 50% of advanced tumors with a specific “driver” mutation in the BRAF gene [1].

Drugs that target cells carrying BRAF mutations initially provided great hope for melanoma, with many reports of dramatic shrinkage of tumors in patients with advanced disease. But almost invariably, the disease recurred and was no longer responsive to those same drugs. A few years ago, researchers thought they’d come up with a solid combination to fight BRAF-mutant melanoma: a one-two punch that paired a BRAF-inhibiting drug with an agent that sensitized the immune system [2]. However, when that combo was tested in humans, the clinical trial had to be stopped early because of serious liver toxicity [3]. Now, in a mouse study published in Science Translational Medicine, NIH-funded researchers at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) provide renewed hope for a safe, effective combination therapy for melanoma—with a strategy that adds a third drug to the mix [4].

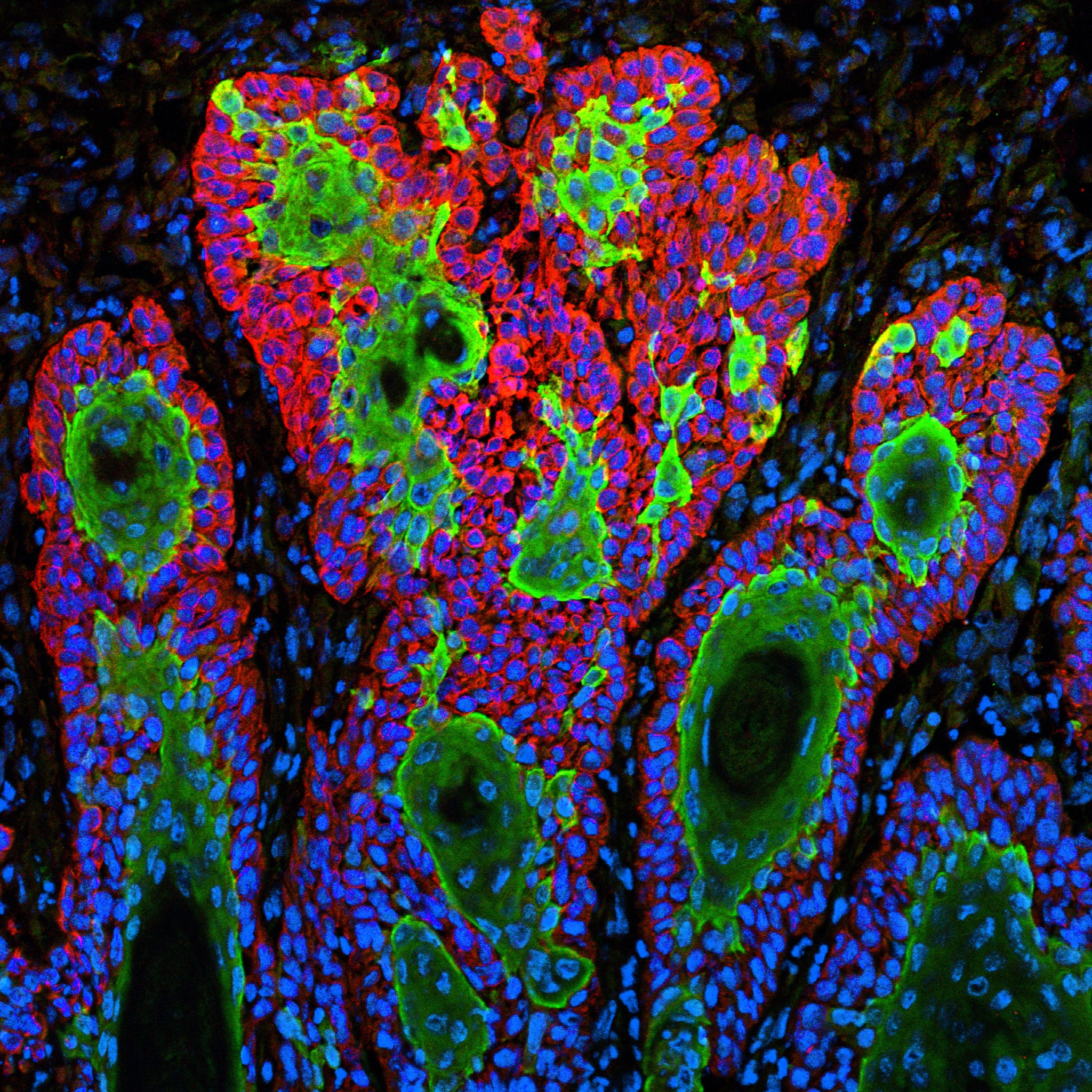

Snapshots of Life: Portrait of Skin Cancer

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Caption: This image shows the uncontrolled growth of cells in squamous cell carcinoma.

Credit: Markus Schober and Elaine Fuchs, The Rockefeller University, New York

For Markus Schober, science is more inspiring when the images are beautiful, even when the subject is not. So, when this biologist was at The Rockefeller University in New York and peered through his microscope at squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), both the diabolical complexity—and the beauty—of this common form of skin cancer caught his eye.

Schober wasn’t the only one who found the image compelling. A panel of judges from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences and the American Society for Cell Biology chose to feature it in their Life: Magnified exhibit, which recently opened at the Washington Dulles International Airport.

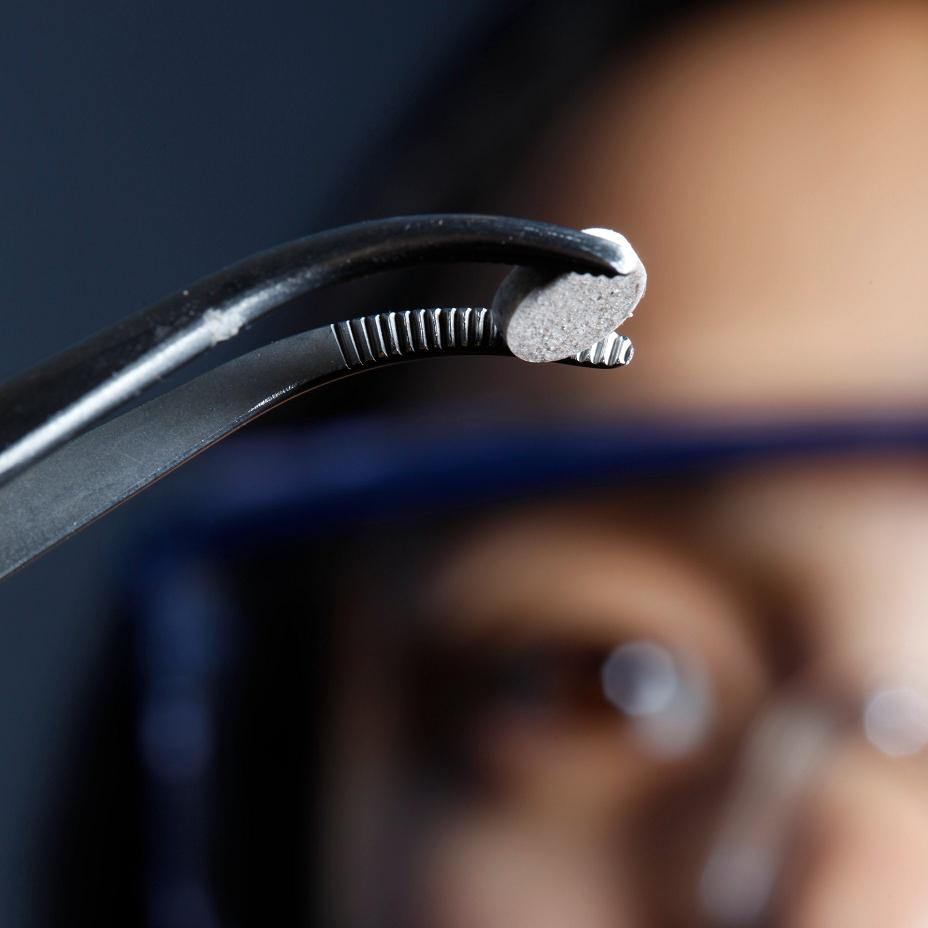

Personalized Cancer Vaccine Enters Human Trials

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Caption: The new melanoma vaccine, which is implanted beneath the skin, is now being tested in human trials.

Credit: Wyss Institute and Amos Chan

This aspirin-sized disk is the first therapeutic cancer vaccine implanted beneath the skin [1]. We know it can eradicate melanoma in mice—the deadliest form of skin cancer—with impressive efficacy [2]. Now, it’s being tested in human trials.

Why Redheads Are More Susceptible to Melanoma

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

We’ve long known that redheads are 10 to 100 times more vulnerable than people with other hair colors to melanoma, a particularly dangerous form of skin cancer. What we haven’t known is why. Why would the hue of your hair have anything to do with your cancer risk? When you consider that melanoma is our most deadly form of skin cancer— expected to cause some 77,000 cases and 9,400 deaths this year alone—it’s important to figure out the connection. A new study [1], led by NIH-funded researchers in Boston, has identified a couple of key links.

We’ve long known that redheads are 10 to 100 times more vulnerable than people with other hair colors to melanoma, a particularly dangerous form of skin cancer. What we haven’t known is why. Why would the hue of your hair have anything to do with your cancer risk? When you consider that melanoma is our most deadly form of skin cancer— expected to cause some 77,000 cases and 9,400 deaths this year alone—it’s important to figure out the connection. A new study [1], led by NIH-funded researchers in Boston, has identified a couple of key links.