gene therapy

Celebrating NIH Science, Blogs, and Blog Readers!

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Happy holidays to one and all! As you may have heard, this is my last holiday season as the Director of the National Institutes of Health (NIH)—a post that I’ve held for the past 12 years and four months under three U.S. Presidents. And, wow, it really does seem like only yesterday that I started this blog!

At the blog’s outset, I said my goal was to “highlight new discoveries in biology and medicine that I think are game changers, noteworthy, or just plain cool.” More than 1,100 posts, 10 million unique visitors, and 13.7 million views later, I hope you’ll agree that goal has been achieved. I’ve also found blogging to be a whole lot of fun, as well as a great way to expand my own horizons and share a little of what I’ve learned about biomedical advances with people all across the nation and around the world.

So, as I sign off as NIH Director and return to my lab at NIH’s National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI), I want to thank everyone who’s ever visited this Blog—from high school students to people with health concerns, from biomedical researchers to policymakers. I hope that the evidence-based information that I’ve provided has helped and informed my readers in some small way.

In this my final post, I’m sharing a short video (see above) that highlights just a few of the blog’s many spectacular images, many of them produced by NIH-funded scientists during the course of their research. In the video, you’ll see a somewhat quirky collection of entries, but hopefully you will sense my enthusiasm for the potential of biomedical research to fight human disease and improve human health—from innovative immunotherapies for treating cancer to the gift of mRNA vaccines to combat a pandemic.

Over the years, I’ve blogged about many of the bold, new frontiers of biomedicine that are now being explored by research teams supported by NIH. Who would have imagined that, within the span of a dozen years, precision medicine would go from being an interesting idea to a driving force behind the largest-ever NIH cohort seeking to individualize the prevention and treatment of common disease? Or that today we’d be deep into investigations of precisely how the human brain works, as well as how human health may benefit from some of the trillions of microbes that call our bodies home?

My posts also delved into some of the amazing technological advances that are enabling breakthroughs across a wide range of scientific fields. These innovative technologies include powerful new ways of mapping the atomic structures of proteins, editing genetic material, and designing improved gene therapies.

So, what’s next for NIH? Let me assure you that NIH is in very steady hands as it heads into a bright horizon brimming with exceptional opportunities for biomedical research. Like you, I look forward to discoveries that will lead us even closer to the life-saving answers that we all want and need.

While we wait for the President to identify a new NIH director, Lawrence Tabak, who has been NIH’s Principal Deputy Director and my right arm for the last decade, will serve as Acting NIH Director. So, keep an eye out for his first post in early January!

As for me, I’ll probably take a little time to catch up on some much-needed sleep, do some reading and writing, and hopefully get out for a few more rides on my Harley with my wife Diane. But there’s plenty of work to do in my lab, where the focus is on type 2 diabetes and a rare disease of premature aging called Hutchinson-Gilford Progeria Syndrome. I’m excited to pursue those research opportunities and see where they lead.

In closing, I’d like to extend my sincere thanks to each of you for your interest in hearing from the NIH Director—and supporting NIH research—over the past 12 years. It’s been an incredible honor to serve you at the helm of this great agency that’s often called the National Institutes of Hope. And now, for one last time, Diane and I take great pleasure in sending you and your loved ones our most heartfelt wishes for Happy Holidays and a Healthy New Year!

Encouraging News on Gene Therapy for Hemophilia A

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

About 20,000 people in the U.S. live with hemophilia A. It’s a rare X-linked genetic disorder that affects predominantly males and causes their blood to clot poorly when healing wounds. For some, routine daily activities can turn into painful medical emergencies to stop internal bleeding, all because of changes in a single gene that disables an essential clotting protein.

Now, results of an early-stage clinical trial, published recently in the New England Journal of Medicine, demonstrate that gene therapy is within reach to produce the essential clotting factor in people with hemophilia A. The results show that, in most of the 18 adult participants, a refined gene therapy strategy produced lasting expression of factor VIII (FVIII), the missing clotting factor in hemophilia A [1]. In fact, gene therapy helped most participants reduce—or, in some cases, completely eliminate—bleeding events.

Currently, the most-common treatment option for males with hemophilia A is intravenous infusion of FVIII concentrate. Though infused FVIII becomes immediately available in the bloodstream, these treatments aren’t a cure and must be repeated, often weekly or every other day, to prevent or control bleeding.

Gene therapy, however, represents a possible cure for hemophilia A. Earlier clinical trials reported some success using benign adeno-associated viruses (AAVs) as the vector to deliver the therapeutic FVIII gene to cells in the liver, where the clotting protein is made. But after a year, those trial participants had a marked decline in FVIII expression. Follow-up studies then found that the decline continued over time, thought to be at least in part because of an immune response to the AAV vector.

In the new study, an NIH-funded team led by Lindsey George and Katherine High of the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia and the University of Pennsylvania, tested their refined delivery system. High is also currently with Asklepios BioPharmaceutical, Inc., Chapel Hill, NC. (Back in the 1970s, she and I were medical students in the same class at the University of North Carolina.) The study was also supported by Spark Therapeutics, Philadelphia.

Trial participants received a single infusion of the novel recombinant AAV-based gene therapy called SPK-8011. It is specifically designed to produce FVIII expression in the liver. In this phase 1/2 clinical trial, which evaluates the safety and initial efficacy of a treatment, participants received one of four different doses of SPK-8011. Most also received steroids to prevent or treat the presumed counterproductive immune response to the therapy.

The researchers followed participants for a year after the experimental treatment, and all enrolled in a follow-up trial for continued observation. During this time, researchers detected no major safety concerns, though several patients had increases in blood levels of a liver enzyme.

The great news is all participants produced the missing FVIII after gene therapy. Twelve of the 16 participants were followed for more than two years and had no apparent decrease in clotting factor activity. This is especially noteworthy because it offers the first demonstration of multiyear stable and durable FVIII expression in individuals with hemophilia A following gene transfer.

Even more encouraging, the men in the trial had more than a 92 percent reduction in bleeding episodes on average. Before treatment, most of the men had 8.5 bleeding episodes per year. After treatment, those events dropped to an average of less than one per year. However, two study participants lost FVIII expression within a year of treatment, presumably due to an immune response to the therapeutic AAV. This finding shows that, while steroids help, they don’t always prevent loss of a therapeutic gene’s expression.

Overall, the findings suggest that AAV-based gene therapy can lead to the durable production of FVIII over several years and significantly reduce bleeding events. The researchers are now exploring possibly more effective ways to control the immune response to AAV in expansion of this phase 1/2 investigation before pursuing a larger phase 3 trial. They’re continuing to monitor participants closely to establish safety and efficacy in the months and years to come.

On a related note, the recently announced Bespoke Gene Therapy Consortium (BGTC), a partnership between NIH and industry, will expand the refined gene therapy approach demonstrated here to more rare and ultrarare diseases. That should make these latest findings extremely encouraging news for the millions of people born with other rare genetic conditions caused by known alterations to a single gene.

Reference:

[1] Multiyear Factor VIII expression after AAV Gene transfer for Hemophilia A. George LA, Monahan PE, Eyster ME, Sullivan SK, Ragni MV, Croteau SE, Rasko JEJ, Recht M, Samelson-Jones BJ, MacDougall A, Jaworski K, Noble R, Curran M, Kuranda K, Mingozzi F, Chang T, Reape KZ, Anguela XM, High KA. N Engl J Med. 2021 Nov 18;385(21):1961-1973.

Links:

Hemophilia A (National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences/NIH)

FAQ About Rare Diseases (National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences/NIH)

Bespoke Gene Therapy Consortium (BGTC) (NIH)

Accelerating Medicines Partnership® (AMP®) (NIH)

Lindsey George (University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia)

Katherine High (University of Pennsylvania)

NIH Support: National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute

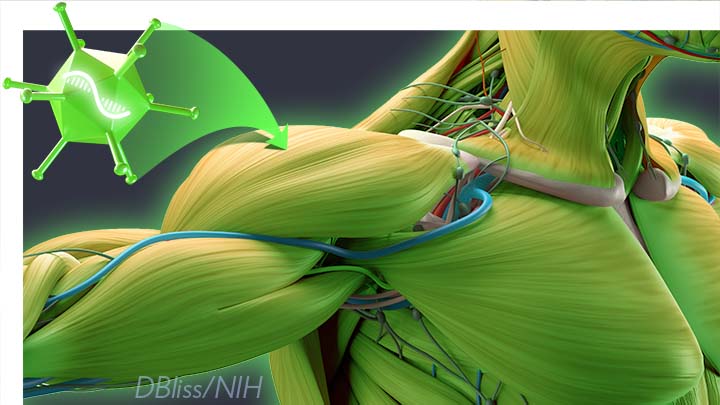

Engineering a Better Way to Deliver Therapeutic Genes to Muscles

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Amid all the progress toward ending the COVID-19 pandemic, it’s worth remembering that researchers here and around the world continue to make important advances in tackling many other serious health conditions. As an inspiring NIH-supported example, I’d like to share an advance on the use of gene therapy for treating genetic diseases that progressively degenerate muscle, such as Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD).

As published recently in the journal Cell, researchers have developed a promising approach to deliver therapeutic genes and gene editing tools to muscle more efficiently, thus requiring lower doses [1]. In animal studies, the new approach has targeted muscle far more effectively than existing strategies. It offers an exciting way forward to reduce unwanted side effects from off-target delivery, which has hampered the development of gene therapy for many conditions.

In boys born with DMD (it’s an X-linked disease and therefore affects males), skeletal and heart muscles progressively weaken due to mutations in a gene encoding a critical muscle protein called dystrophin. By age 10, most boys require a wheelchair. Sadly, their life expectancy remains less than 30 years.

The hope is gene therapies will one day treat or even cure DMD and allow people with the disease to live longer, high-quality lives. Unfortunately, the benign adeno-associated viruses (AAVs) traditionally used to deliver the healthy intact dystrophin gene into cells mostly end up in the liver—not in muscles. It’s also the case for gene therapy of many other muscle-wasting genetic diseases.

The heavy dose of viral vector to the liver is not without concern. Recently and tragically, there have been deaths in a high-dose AAV gene therapy trial for X-linked myotubular myopathy (XLMTM), a different disorder of skeletal muscle in which there may already be underlying liver disease, potentially increasing susceptibility to toxicity.

To correct this concerning routing error, researchers led by Mohammadsharif Tabebordbar in the lab of Pardis Sabeti, Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard and Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, have now assembled an optimized collection of AAVs. They have been refined to be about 10 times better at reaching muscle fibers than those now used in laboratory studies and clinical trials. In fact, researchers call them myotube AAVs, or MyoAAVs.

MyoAAVs can deliver therapeutic genes to muscle at much lower doses—up to 250 times lower than what’s needed with traditional AAVs. While this approach hasn’t yet been tried in people, animal studies show that MyoAAVs also largely avoid the liver, raising the prospect for more effective gene therapies without the risk of liver damage and other serious side effects.

In the Cell paper, the researchers demonstrate how they generated MyoAAVs, starting out with the commonly used AAV9. Their goal was to modify the outer protein shell, or capsid, to create an AAV that would be much better at specifically targeting muscle. To do so, they turned to their capsid engineering platform known as, appropriately enough, DELIVER. It’s short for Directed Evolution of AAV capsids Leveraging In Vivo Expression of transgene RNA.

Here’s how DELIVER works. The researchers generate millions of different AAV capsids by adding random strings of amino acids to the portion of the AAV9 capsid that binds to cells. They inject those modified AAVs into mice and then sequence the RNA from cells in muscle tissue throughout the body. The researchers want to identify AAVs that not only enter muscle cells but that also successfully deliver therapeutic genes into the nucleus to compensate for the damaged version of the gene.

This search delivered not just one AAV—it produced several related ones, all bearing a unique surface structure that enabled them specifically to target muscle cells. Then, in collaboration with Amy Wagers, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, the team tested their MyoAAV toolset in animal studies.

The first cargo, however, wasn’t a gene. It was the gene-editing system CRISPR-Cas9. The team found the MyoAAVs correctly delivered the gene-editing system to muscle cells and also repaired dysfunctional copies of the dystrophin gene better than the CRISPR cargo carried by conventional AAVs. Importantly, the muscles of MyoAAV-treated animals also showed greater strength and function.

Next, the researchers teamed up with Alan Beggs, Boston Children’s Hospital, and found that MyoAAV was effective in treating mouse models of XLMTM. This is the very condition mentioned above, in which very high dose gene therapy with a current AAV vector has led to tragic outcomes. XLMTM mice normally die in 10 weeks. But, after receiving MyoAAV carrying a corrective gene, all six mice had a normal lifespan. By comparison, mice treated in the same way with traditional AAV lived only up to 21 weeks of age. What’s more, the researchers used MyoAAV at a dose 100 times lower than that currently used in clinical trials.

While further study is needed before this approach can be tested in people, MyoAAV was also used to successfully introduce therapeutic genes into human cells in the lab. This suggests that the early success in animals might hold up in people. The approach also has promise for developing AAVs with potential for targeting other organs, thereby possibly providing treatment for a wide range of genetic conditions.

The new findings are the result of a decade of work from Tabebordbar, the study’s first author. His tireless work is also personal. His father has a rare genetic muscle disease that has put him in a wheelchair. With this latest advance, the hope is that the next generation of promising gene therapies might soon make its way to the clinic to help Tabebordbar’s father and so many other people.

Reference:

[1] Directed evolution of a family of AAV capsid variants enabling potent muscle-directed gene delivery across species. Tabebordbar M, Lagerborg KA, Stanton A, King EM, Ye S, Tellez L, Krunnfusz A, Tavakoli S, Widrick JJ, Messemer KA, Troiano EC, Moghadaszadeh B, Peacker BL, Leacock KA, Horwitz N, Beggs AH, Wagers AJ, Sabeti PC. Cell. 2021 Sep 4:S0092-8674(21)01002-3.

Links:

Muscular Dystrophy Information Page (National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke/NIH)

X-linked myotubular myopathy (Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center/National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences/NIH)

Somatic Cell Genome Editing (Common Fund/NIH)

Mohammadsharif Tabebordbar (Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard and Harvard University, Cambridge, MA)

Sabeti Lab (Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard and Harvard University)

NIH Support: Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development; Common Fund

Hope on the Hill

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Gene Therapy Shows Promise Repairing Brain Tissue Damaged by Stroke

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

It’s a race against time when someone suffers a stroke caused by a blockage of a blood vessel supplying the brain. Unless clot-busting treatment is given within a few hours after symptoms appear, vast numbers of the brain’s neurons die, often leading to paralysis or other disabilities. It would be great to have a way to replace those lost neurons. Thanks to gene therapy, some encouraging strides are now being made.

In a recent study in Molecular Therapy, researchers reported that, in their mouse and rat models of ischemic stroke, gene therapy could actually convert the brain’s support cells into new, fully functional neurons [1]. Even better, after gaining the new neurons, the animals had improved motor and memory skills.

For the team led by Gong Chen, Penn State, University Park, the quest to replace lost neurons in the brain began about a decade ago. While searching for the right approach, Chen noticed other groups had learned to reprogram fibroblasts into stem cells and make replacement neural cells.

As innovative as this work was at the time, it was performed mostly in lab Petri dishes. Chen and his colleagues thought, why not reprogram cells already in the brain?

They turned their attention to the brain’s billions of supportive glial cells. Unlike neurons, glial cells divide and replicate. They also are known to survive and activate following a brain injury, remaining at the wound and ultimately forming a scar. This same process had also been observed in the brain following many types of injury, including stroke and neurodegenerative conditions such as Alzheimer’s disease.

To Chen’s NIH-supported team, it looked like glial cells might be a perfect target for gene therapies to replace lost neurons. As reported about five years ago, the researchers were on the right track [2].

The Chen team showed it was possible to reprogram glial cells in the brain into functional neurons. They succeeded using a genetically engineered retrovirus that delivered a single protein called NeuroD1. It’s a neural transcription factor that switches genes on and off in neural cells and helps to determine their cell fate. The newly generated neurons were also capable of integrating into brain circuits to repair damaged tissue.

There was one major hitch: the NeuroD1 retroviral vector only reprogrammed actively dividing glial cells. That suggested their strategy likely couldn’t generate the large numbers of new cells needed to repair damaged brain tissue following a stroke.

Fast-forward a couple of years, and improved adeno-associated viral vectors (AAV) have emerged as a major alternative to retroviruses for gene therapy applications. This was exactly the breakthrough that the Chen team needed. The AAVs can reprogram glial cells whether they are dividing or not.

In the new study, Chen’s team, led by post-doc Yu-Chen Chen, put this new gene therapy system to work, and the results are quite remarkable. In a mouse model of ischemic stroke, the researchers showed the treatment could regenerate about a third of the total lost neurons by preferentially targeting reactive, scar-forming glial cells. The conversion of those reactive glial cells into neurons also protected another third of the neurons from injury.

Studies in brain slices showed that the replacement neurons were fully functional and appeared to have made the needed neural connections in the brain. Importantly, their studies also showed that the NeuroD1 gene therapy led to marked improvements in the functional recovery of the mice after a stroke.

In fact, several tests of their ability to make fine movements with their forelimbs showed about a 60 percent improvement within 20 to 60 days of receiving the NeuroD1 therapy. Together with study collaborator and NIH grantee Gregory Quirk, University of Puerto Rico, San Juan, they went on to show similar improvements in the ability of rats to recover from stroke-related deficits in memory.

While further study is needed, the findings in rodents offer encouraging evidence that treatments to repair the brain after a stroke or other injury may be on the horizon. In the meantime, the best strategy for limiting the number of neurons lost due to stroke is to recognize the signs and get to a well-equipped hospital or call 911 right away if you or a loved one experience them. Those signs include: sudden numbness or weakness of one side of the body; confusion; difficulty speaking, seeing, or walking; and a sudden, severe headache with unknown causes. Getting treatment for this kind of “brain attack” within four hours of the onset of symptoms can make all the difference in recovery.

References:

[1] A NeuroD1 AAV-Based gene therapy for functional brain repair after ischemic injury through in vivo astrocyte-to-neuron conversion. Chen Y-C et al. Molecular Therapy. Published online September 6, 2019.

[2] In vivo direct reprogramming of reactive glial cells into functional neurons after brain injury and in an Alzheimer’s disease model. Guo Z, Zhang L, Wu Z, Chen Y, Wang F, Chen G. Cell Stem Cell. 2014 Feb 6;14(2):188-202.

Links:

Stroke (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute/NIH)

Gene Therapy (National Human Genome Research Institute/NIH)

Chen Lab (Penn State, University Park)

NIH Support: National Institute on Aging; National Institute of Mental Health

The Amazing Brain: Making Up for Lost Vision

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Recently, I’ve highlighted just a few of the many amazing advances coming out of the NIH-led Brain Research through Advancing Innovative Neurotechnologies® (BRAIN) Initiative. And for our grand finale, I’d like to share a cool video that reveals how this revolutionary effort to map the human brain is opening up potential plans to help people with disabilities, such as vision loss, that were once unimaginable.

This video, produced by Jordi Chanovas and narrated by Stephen Macknik, State University of New York Downstate Health Sciences University, Brooklyn, outlines a new strategy aimed at restoring loss of central vision in people with age-related macular degeneration (AMD), a leading cause of vision loss among people age 50 and older. The researchers’ ultimate goal is to give such people the ability to see the faces of their loved ones or possibly even read again.

In the innovative approach you see here, neuroscientists aren’t even trying to repair the part of the eye destroyed by AMD: the light-sensitive retina. Instead, they are attempting to recreate the light-recording function of the retina within the brain itself.

How is that possible? Normally, the retina streams visual information continuously to the brain’s primary visual cortex, which receives the information and processes it into the vision that allows you to read these words. In folks with AMD-related vision loss, even though many cells in the center of the retina have stopped streaming, the primary visual cortex remains fully functional to receive and process visual information.

About five years ago, Macknik and his collaborator Susana Martinez-Conde, also at Downstate, wondered whether it might be possible to circumvent the eyes and stream an alternative source of visual information to the brain’s primary visual cortex, thereby restoring vision in people with AMD. They sketched out some possibilities and settled on an innovative system that they call OBServ.

Among the vital components of this experimental system are tiny, implantable neuro-prosthetic recording devices. Created in the Macknik and Martinez-Conde labs, this 1-centimeter device is powered by induction coils similar to those in the cochlear implants used to help people with profound hearing loss. The researchers propose to surgically implant two of these devices in the rear of the brain, where they will orchestrate the visual process.

For technical reasons, the restoration of central vision will likely be partial, with the window of vision spanning only about the size of one-third of an adult thumbnail held at arm’s length. But researchers think that would be enough central vision for people with AMD to regain some of their lost independence.

As demonstrated in this video from the BRAIN Initiative’s “Show Us Your Brain!” contest, here’s how researchers envision the system would ultimately work:

• A person with vision loss puts on a specially designed set of glasses. Each lens contains two cameras: one to record visual information in the person’s field of vision; the other to track that person’s eye movements enabled by residual peripheral vision.

• The eyeglass cameras wirelessly stream the visual information they have recorded to two neuro-prosthetic devices implanted in the rear of the brain.

• The neuro-prosthetic devices process and project this information onto a specific set of excitatory neurons in the brain’s hard-wired visual pathway. Researchers have previously used genetic engineering to turn these neurons into surrogate photoreceptor cells, which function much like those in the eye’s retina.

• The surrogate photoreceptor cells in the brain relay visual information to the primary visual cortex for processing.

• All the while, the neuro-prosthetic devices perform quality control of the visual signals, calibrating them to optimize their contrast and clarity.

While this might sound like the stuff of science-fiction (and this actual application still lies several years in the future), the OBServ project is now actually conceivable thanks to decades of advances in the fields of neuroscience, vision, bioengineering, and bioinformatics research. All this hard work has made the primary visual cortex, with its switchboard-like wiring system, among the brain’s best-understood regions.

OBServ also has implications that extend far beyond vision loss. This project provides hope that once other parts of the brain are fully mapped, it may be possible to design equally innovative systems to help make life easier for people with other disabilities and conditions.

Links:

Age-Related Macular Degeneration (National Eye Institute/NIH)

Macknik Lab (SUNY Downstate Health Sciences University, Brooklyn)

Martinez-Conde Laboratory (SUNY Downstate Health Sciences University)

Show Us Your Brain! (BRAIN Initiative/NIH)

Brain Research through Advancing Innovative Neurotechnologies® (BRAIN) Initiative (NIH)

NIH Support: BRAIN Initiative

A CRISPR Approach to Treating Sickle Cell

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Recently, CBS’s “60 Minutes” highlighted the story of Jennelle Stephenson, a brave young woman with sickle cell disease (SCD). Jennelle now appears potentially cured of this devastating condition, thanks to an experimental gene therapy being tested at the NIH Clinical Center in Bethesda, MD. As groundbreaking as this research may be, it’s among a variety of innovative strategies now being tried to cure SCD and other genetic diseases that have long seemed out of reach.

One particularly exciting approach involves using gene editing to increase levels of fetal hemoglobin (HbF) in the red blood cells of people with SCD. Shortly after birth, babies usually stop producing HbF, and switch over to the adult form of hemoglobin. But rare individuals continue to make high levels of HbF throughout their lives. This is referred to as hereditary persistence of fetal hemoglobin (HPFH). (My own postdoctoral research in the early 1980s discovered some of the naturally occurring DNA mutations that lead to this condition.)

Individuals with HPFH are entirely healthy. Strikingly, rare individuals with SCD who also have HPFH have an extremely mild version of sickle cell disease—essentially the presence of significant quantities of HbF provides protection against sickling. So, researchers have been exploring ways to boost HbF in everyone with SCD—and gene editing may provide an effective, long-lasting way to do this.

Clinical trials of this approach are already underway. And new findings reported in Nature Medicine show it may be possible to make the desired edits even more efficiently, raising the possibility that a single infusion of gene-edited cells might be able to cure SCD [1].

Sickle cell disease is caused by a specific point mutation in a gene that codes for the beta chain of hemoglobin. People with just one copy of this mutation have sickle cell trait and are generally healthy. But those who inherit two mutant copies of this gene suffer lifelong consequences of the presence of this abnormal protein. Their red blood cells—normally flexible and donut-shaped—assume the sickled shape that gives SCD its name. The sickled cells clump together and stick in small blood vessels, resulting in severe pain, anemia, stroke, pulmonary hypertension, organ failure, and far too often, early death.

Eleven years ago, a team led by Vijay Sankaran and Stuart Orkin at Boston Children’s Hospital and the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute discovered that a protein called BCL11A seemed to determine HbF levels [2]. Subsequent work showed the protein actually works as a master mediator of the switch from fetal to adult hemoglobin, which normally occurs shortly after birth.

Five years ago, Orkin and Daniel Bauer identified a specific enhancer of BCL11A expression that could be an attractive target for gene editing [3]. They could knock out the enhancer in the bone marrow, and BCL11A would not be produced, allowing HbF to stay switched on.

Because the BCL11A protein is required to turn off production of HbF in red cells. the researchers had another idea. They thought it might be possible to keep HbF on permanently by disrupting BCL11A in blood-forming hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs). The hope was that such a treatment might offer people with SCD a permanent supply of healthy red blood cells.

Fast-forward to the present, and researchers are now testing the ability of gene editing tools to cure the disease. A favorite editing system is CRISPR, which I’ve highlighted on my blog.

CRISPR is a highly precise gene-editing tool that relies on guide RNA molecules to direct a scissor-like Cas9 enzyme to just the right spot in the genome to correct the misspelling. The gene-editing treatment involves removing bone marrow from a patient, modifying the HSCs outside the body using CRISPR gene-editing tools, and then returning them back to the patient. Preclinical studies had shown that CRISPR can be effective in editing BCL11A to boost HbF production.

But questions lingered about the editing efficiency in HSCs versus more common, shorter-lived progenitor cells found in bone marrow samples. The efficiency greatly influences how long the edited cells might benefit patients. Bauer’s team saw room for improvement and, as the new study shows, they were right.

To produce lasting HbF production, it’s important to edit as many HSCs as possible. But it turns out that HSCs are more resistant to editing than other types of cells in bone marrow. With a series of adjustments to the gene-editing protocol, including use of an optimized version of the Cas9 protein, the researchers showed they could push the number of edited genes from about 80 percent to about 95 percent.

Their studies show that the most frequent Cas9 edits in HSCs are tiny insertions of a single DNA “letter.” With that slight edit to the BCL11A gene, HSCs reprogram themselves in a way that ensures long-term HbF production.

As a first test of their CRISPR-edited human HSCs, the researchers carried out the editing on HSCs derived from patients with SCD. Then they transferred the editing cells into immune-compromised mice. Four months later, the mice continued to produce red blood cells that produced high levels of HbF and resisted sickling. Bauer says they’re already taking steps to begin testing cells edited with their optimized protocol in a clinical trial.

What’s truly exciting is that the first U.S. human clinical trials of such a gene-editing approach for SCD are already underway, led by CRISPR Therapeutics/Vertex Pharmaceuticals and Sangamo Therapeutics/Sanofi. In January, CRISPR Therapeutics/Vertex Pharmaceuticals announced that the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) had granted Fast Track Designation for their CRISPR-based treatment called CTX001 [4].

In that recent “60 Minutes” segment, I dared to suggest that we now have what looks like a cure for SCD. As shown by this new work and the clinical trials underway, we in fact may soon have multiple different strategies to provide cures for this devastating disease. And if this can work for sickle cell, a similar strategy might work for other genetic conditions that currently lack any effective treatment.

References:

[1] Highly efficient therapeutic gene editing of human hematopoietic stem cells. Wu Y, Zeng J, Roscoe BP, Liu P, Yao Q, Lazzarotto CR, Clement K, Cole MA, Luk K, Baricordi C, Shen AH, Ren C, Esrick EB, Manis JP, Dorfman DM, Williams DA, Biffi A, Brugnara C, Biasco L, Brendel C, Pinello L, Tsai SQ, Wolfe SA, Bauer DE. Nat Med. 2019 Mar 25.

[2] Human fetal hemoglobin expression is regulated by the developmental stage-specific repressor BCL11A. Sankaran VG, Menne TF, Xu J, Akie TE, Lettre G, Van Handel B, Mikkola HK, Hirschhorn JN, Cantor AB, Orkin SH.Science. 2008 Dec 19;322(5909):1839-1842.

[3] An erythroid enhancer of BCL11A subject to genetic variation determines fetal hemoglobin level. Bauer DE, Kamran SC, Lessard S, Xu J, Fujiwara Y, Lin C, Shao Z, Canver MC, Smith EC, Pinello L, Sabo PJ, Vierstra J, Voit RA, Yuan GC, Porteus MH, Stamatoyannopoulos JA, Lettre G, Orkin SH. Science. 2013 Oct 11;342(6155):253-257.

[4] CRISPR Therapeutics and Vertex Announce FDA Fast Track Designation for CTX001 for the Treatment of Sickle Cell Disease, CRISPR Therapeutics News Release, Jan. 4, 2019.

Links:

Sickle Cell Disease (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute/NIH)

Cure Sickle Cell Initiative (NHLBI)

What are Genome Editing and CRISPR-Cas9? (National Library of Medicine/NIH)

Could Gene Therapy Cure Sickle Cell Anemia? (CBS News)

Daniel Bauer (Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston)

Somatic Cell Genome Editing Program (Common Fund/NIH)

NIH Support: National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; National Institute of General Medical Sciences; National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases; National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases

Next Page