photoreceptor cells

The Amazing Brain: Making Up for Lost Vision

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Recently, I’ve highlighted just a few of the many amazing advances coming out of the NIH-led Brain Research through Advancing Innovative Neurotechnologies® (BRAIN) Initiative. And for our grand finale, I’d like to share a cool video that reveals how this revolutionary effort to map the human brain is opening up potential plans to help people with disabilities, such as vision loss, that were once unimaginable.

This video, produced by Jordi Chanovas and narrated by Stephen Macknik, State University of New York Downstate Health Sciences University, Brooklyn, outlines a new strategy aimed at restoring loss of central vision in people with age-related macular degeneration (AMD), a leading cause of vision loss among people age 50 and older. The researchers’ ultimate goal is to give such people the ability to see the faces of their loved ones or possibly even read again.

In the innovative approach you see here, neuroscientists aren’t even trying to repair the part of the eye destroyed by AMD: the light-sensitive retina. Instead, they are attempting to recreate the light-recording function of the retina within the brain itself.

How is that possible? Normally, the retina streams visual information continuously to the brain’s primary visual cortex, which receives the information and processes it into the vision that allows you to read these words. In folks with AMD-related vision loss, even though many cells in the center of the retina have stopped streaming, the primary visual cortex remains fully functional to receive and process visual information.

About five years ago, Macknik and his collaborator Susana Martinez-Conde, also at Downstate, wondered whether it might be possible to circumvent the eyes and stream an alternative source of visual information to the brain’s primary visual cortex, thereby restoring vision in people with AMD. They sketched out some possibilities and settled on an innovative system that they call OBServ.

Among the vital components of this experimental system are tiny, implantable neuro-prosthetic recording devices. Created in the Macknik and Martinez-Conde labs, this 1-centimeter device is powered by induction coils similar to those in the cochlear implants used to help people with profound hearing loss. The researchers propose to surgically implant two of these devices in the rear of the brain, where they will orchestrate the visual process.

For technical reasons, the restoration of central vision will likely be partial, with the window of vision spanning only about the size of one-third of an adult thumbnail held at arm’s length. But researchers think that would be enough central vision for people with AMD to regain some of their lost independence.

As demonstrated in this video from the BRAIN Initiative’s “Show Us Your Brain!” contest, here’s how researchers envision the system would ultimately work:

• A person with vision loss puts on a specially designed set of glasses. Each lens contains two cameras: one to record visual information in the person’s field of vision; the other to track that person’s eye movements enabled by residual peripheral vision.

• The eyeglass cameras wirelessly stream the visual information they have recorded to two neuro-prosthetic devices implanted in the rear of the brain.

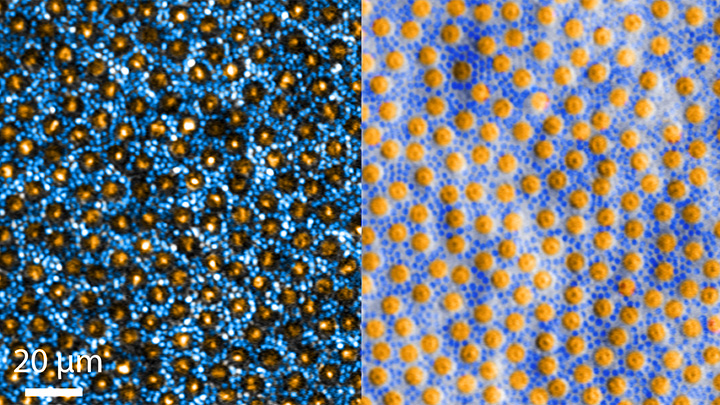

• The neuro-prosthetic devices process and project this information onto a specific set of excitatory neurons in the brain’s hard-wired visual pathway. Researchers have previously used genetic engineering to turn these neurons into surrogate photoreceptor cells, which function much like those in the eye’s retina.

• The surrogate photoreceptor cells in the brain relay visual information to the primary visual cortex for processing.

• All the while, the neuro-prosthetic devices perform quality control of the visual signals, calibrating them to optimize their contrast and clarity.

While this might sound like the stuff of science-fiction (and this actual application still lies several years in the future), the OBServ project is now actually conceivable thanks to decades of advances in the fields of neuroscience, vision, bioengineering, and bioinformatics research. All this hard work has made the primary visual cortex, with its switchboard-like wiring system, among the brain’s best-understood regions.

OBServ also has implications that extend far beyond vision loss. This project provides hope that once other parts of the brain are fully mapped, it may be possible to design equally innovative systems to help make life easier for people with other disabilities and conditions.

Links:

Age-Related Macular Degeneration (National Eye Institute/NIH)

Macknik Lab (SUNY Downstate Health Sciences University, Brooklyn)

Martinez-Conde Laboratory (SUNY Downstate Health Sciences University)

Show Us Your Brain! (BRAIN Initiative/NIH)

Brain Research through Advancing Innovative Neurotechnologies® (BRAIN) Initiative (NIH)

NIH Support: BRAIN Initiative

Glowing Proof of Gene Therapy Delivered to the Eye

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Caption: A cross section from the retina of a non-human primate shows evidence of the production of a glowing green protein, made from genes the virus delivered —proof that the genetic cargo entered all layers of the outer retina. Cell nuclei are labeled in blue and the laminin protein is labeled in red.

Credit: Leah Byrne, University of California, Berkeley

Scientists based at Berkeley have engineered a virus that can carry healthy genes through the jelly-like substance in the eye to reach the cells that make up the retina—the back of the eye that detects light.