retina

Human Brain Compresses Working Memories into Low-Res ‘Summaries’

Posted on by Lawrence Tabak, D.D.S., Ph.D.

You have probably done it already a few times today. Paused to remember a password, a shopping list, a phone number, or maybe the score to last night’s ballgame. The ability to store and recall needed information, called working memory, is essential for most of the human brain’s higher cognitive processes.

Researchers are still just beginning to piece together how working memory functions. But recently, NIH-funded researchers added an intriguing new piece to this neurobiological puzzle: how visual working memories are “formatted” and stored in the brain.

The findings, published in the journal Neuron, show that the visual cortex—the brain’s primary region for receiving, integrating, and processing visual information from the eye’s retina—acts more like a blackboard than a camera. That is, the visual cortex doesn’t photograph all the complex details of a visual image, such as the color of paper on which your password is written or the precise series of lines that make up the letters. Instead, it recodes visual information into something more like simple chalkboard sketches.

The discovery suggests that those pared down, low-res representations serve as a kind of abstract summary, capturing the relevant information while discarding features that aren’t relevant to the task at hand. It also shows that different visual inputs, such as spatial orientation and motion, may be stored in virtually identical, shared memory formats.

The new study, from Clayton Curtis and Yuna Kwak, New York University, New York, builds upon a known fundamental aspect of working memory. Many years ago, it was determined that the human brain tends to recode visual information. For instance, if passed a 10-digit phone number on a card, the visual information gets recoded and stored in the brain as the sounds of the numbers being read aloud.

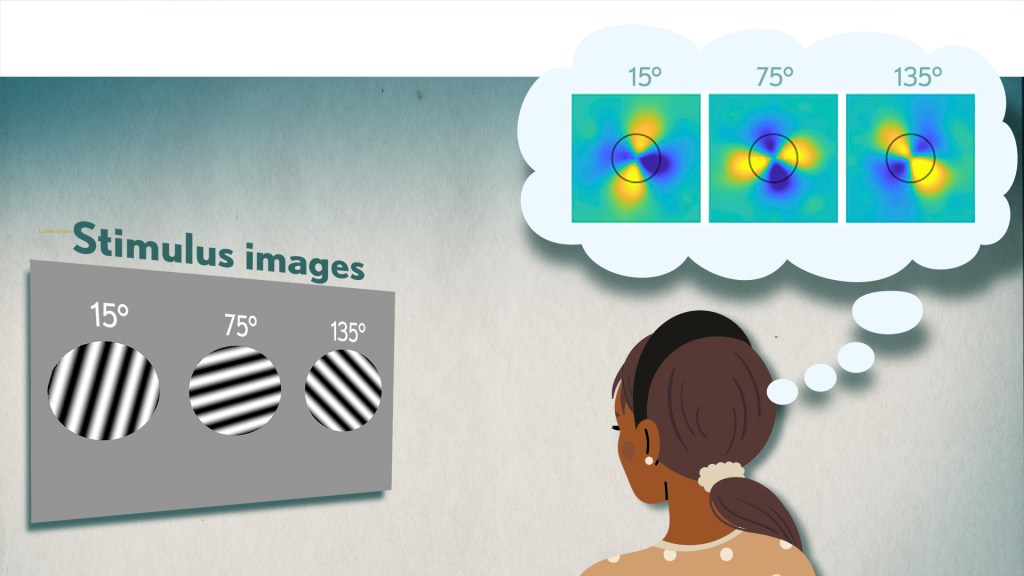

Curtis and Kwak wanted to learn more about how the brain formats representations of working memory in patterns of brain activity. To find out, they measured brain activity with functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) while participants used their visual working memory.

In each test, study participants were asked to remember a visual stimulus presented to them for 12 seconds and then make a memory-based judgment on what they’d just seen. In some trials, as shown in the image above, participants were shown a tilted grating, a series of black and white lines oriented at a particular angle. In others, they observed a cloud of dots, all moving in a direction to represent those same angles. After a short break, participants were asked to recall and precisely indicate the angle of the grating’s tilt or the dot cloud’s motion as accurately as possible.

It turned out that either visual stimulus—the grating or moving dots—resulted in the same patterns of neural activity in the visual cortex and parietal cortex. The parietal cortex is a part of the brain used in memory processing and storage.

These two distinct visual memories carrying the same relevant information seemed to have been recoded into a shared abstract memory format. As a result, the pattern of brain activity trained to recall motion direction was indistinguishable from that trained to recall the grating orientation.

This result indicated that only the task-relevant features of the visual stimuli had been extracted and recoded into a shared memory format. But Curtis and Kwak wondered whether there might be more to this finding.

To take a closer look, they used a sophisticated model that allowed them to project the three-dimensional patterns of brain activity into a more-informative, two-dimensional representation of visual space. And, indeed, their analysis of the data revealed a line-like pattern, similar to a chalkboard sketch that’s oriented at the relevant angles.

The findings suggest that participants weren’t actually remembering the grating or a complex cloud of moving dots at all. Instead, they’d compressed the images into a line representing the angle that they’d been asked to remember.

Many questions remain about how remembering a simple angle, a relatively straightforward memory formation, will translate to the more-complex sets of information stored in our working memory. On a technical level, though, the findings show that working memory can now be accessed and captured in ways that hadn’t been possible before. This will help to delineate the commonalities in working memory formation and the possible differences, whether it’s remembering a password, a shopping list, or the score of your team’s big victory last night.

Reference:

[1] Unveiling the abstract format of mnemonic representations. Kwak Y, Curtis CE. Neuron. 2022, April 7; 110(1-7).

Links:

Working Memory (National Institute of Mental Health/NIH)

The Curtis Lab (New York University, New York)

NIH Support: National Eye Institute

Artificial Intelligence Getting Smarter! Innovations from the Vision Field

Posted on by Michael F. Chiang, M.D., National Eye Institute

One of many health risks premature infants face is retinopathy of prematurity (ROP), a leading cause of childhood blindness worldwide. ROP causes abnormal blood vessel growth in the light-sensing eye tissue called the retina. Left untreated, ROP can lead to lead to scarring, retinal detachment, and blindness. It’s the disease that caused singer and songwriter Stevie Wonder to lose his vision.

Now, effective treatments are available—if the disease is diagnosed early and accurately. Advancements in neonatal care have led to the survival of extremely premature infants, who are at highest risk for severe ROP. Despite major advancements in diagnosis and treatment, tragically, about 600 infants in the U.S. still go blind each year from ROP. This disease is difficult to diagnose and manage, even for the most experienced ophthalmologists. And the challenges are much worse in remote corners of the world that have limited access to ophthalmic and neonatal care.

Artificial intelligence (AI) is helping bridge these gaps. Prior to my tenure as National Eye Institute (NEI) director, I helped develop a system called i-ROP Deep Learning (i-ROP DL), which automates the identification of ROP. In essence, we trained a computer to identify subtle abnormalities in retinal blood vessels from thousands of images of premature infant retinas. Strikingly, the i-ROP DL artificial intelligence system outperformed even international ROP experts [1]. This has enormous potential to improve the quality and delivery of eye care to premature infants worldwide.

Of course, the promise of medical artificial intelligence extends far beyond ROP. In 2018, the FDA approved the first autonomous AI-based diagnostic tool in any field of medicine [2]. Called IDx-DR, the system streamlines screening for diabetic retinopathy (DR), and its results require no interpretation by a doctor. DR occurs when blood vessels in the retina grow irregularly, bleed, and potentially cause blindness. About 34 million people in the U.S. have diabetes, and each is at risk for DR.

As with ROP, early diagnosis and intervention is crucial to preventing vision loss to DR. The American Diabetes Association recommends people with diabetes see an eye care provider annually to have their retinas examined for signs of DR. Yet fewer than 50 percent of Americans with diabetes receive these annual eye exams.

The IDx-DR system was conceived by Michael Abramoff, an ophthalmologist and AI expert at the University of Iowa, Iowa City. With NEI funding, Abramoff used deep learning to design a system for use in a primary-care medical setting. A technician with minimal ophthalmology training can use the IDx-DR system to scan a patient’s retinas and get results indicating whether a patient should be sent to an eye specialist for follow-up evaluation or to return for another scan in 12 months.

Many other methodological innovations in AI have occurred in ophthalmology. That’s because imaging is so crucial to disease diagnosis and clinical outcome data are so readily available. As a result, AI-based diagnostic systems are in development for many other eye diseases, including cataract, age-related macular degeneration (AMD), and glaucoma.

Rapid advances in AI are occurring in other medical fields, such as radiology, cardiology, and dermatology. But disease diagnosis is just one of many applications for AI. Neurobiologists are using AI to answer questions about retinal and brain circuitry, disease modeling, microsurgical devices, and drug discovery.

If it sounds too good to be true, it may be. There’s a lot of work that remains to be done. Significant challenges to AI utilization in science and medicine persist. For example, researchers from the University of Washington, Seattle, last year tested seven AI-based screening algorithms that were designed to detect DR. They found under real-world conditions that only one outperformed human screeners [3]. A key problem is these AI algorithms need to be trained with more diverse images and data, including a wider range of races, ethnicities, and populations—as well as different types of cameras.

How do we address these gaps in knowledge? We’ll need larger datasets, a collaborative culture of sharing data and software libraries, broader validation studies, and algorithms to address health inequities and to avoid bias. The NIH Common Fund’s Bridge to Artificial Intelligence (Bridge2AI) project and NIH’s Artificial Intelligence/Machine Learning Consortium to Advance Health Equity and Researcher Diversity (AIM-AHEAD) Program project will be major steps toward addressing those gaps.

So, yes—AI is getting smarter. But harnessing its full power will rely on scientists and clinicians getting smarter, too.

References:

[1] Automated diagnosis of plus disease in retinopathy of prematurity using deep convolutional neural networks. Brown JM, Campbell JP, Beers A, Chang K, Ostmo S, Chan RVP, Dy J, Erdogmus D, Ioannidis S, Kalpathy-Cramer J, Chiang MF; Imaging and Informatics in Retinopathy of Prematurity (i-ROP) Research Consortium. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2018 Jul 1;136(7):803-810.

[2] FDA permits marketing of artificial intelligence-based device to detect certain diabetes-related eye problems. Food and Drug Administration. April 11, 2018.

[3] Multicenter, head-to-head, real-world validation study of seven automated artificial intelligence diabetic retinopathy screening systems. Lee AY, Yanagihara RT, Lee CS, Blazes M, Jung HC, Chee YE, Gencarella MD, Gee H, Maa AY, Cockerham GC, Lynch M, Boyko EJ. Diabetes Care. 2021 May;44(5):1168-1175.

Links:

Retinopathy of Prematurity (National Eye Institute/NIH)

Diabetic Eye Disease (NEI)

Michael Abramoff (University of Iowa, Iowa City)

Bridge to Artificial Intelligence (Common Fund/NIH)

[Note: Acting NIH Director Lawrence Tabak has asked the heads of NIH’s institutes and centers to contribute occasional guest posts to the blog as a way to highlight some of the cool science that they support and conduct. This is the second in the series of NIH institute and center guest posts that will run until a new permanent NIH director is in place.]

Nano-Sized Solution for Efficient and Versatile CRISPR Gene Editing

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

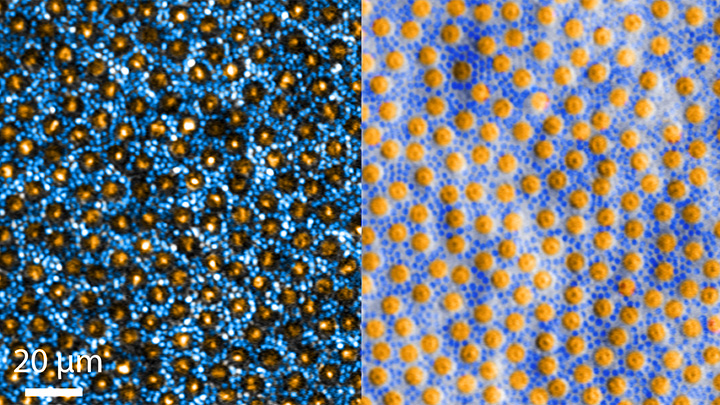

Credit: Guojun Chen and Amr Abdeen, University of Wisconsin-Madison

If used to make non-heritable genetic changes, CRISPR gene-editing technology holds tremendous promise for treating or curing a wide range of devastating disorders, including sickle cell disease, vision loss, and muscular dystrophy. Early efforts to deliver CRISPR-based therapies to affected tissues in a patient’s body typically have involved packing the gene-editing tools into viral vectors, which may cause unwanted immune reactions and other adverse effects.

Now, NIH-supported researchers have developed an alternative CRISPR delivery system: nanocapsules. Not only do these tiny, synthetic capsules appear to pose a lower risk of side effects, they can be precisely customized to deliver their gene-editing payloads to many different types of cells or tissues in the body, which can be extremely tough to do with a virus. Another advantage of these gene-editing nanocapsules is that they can be freeze-dried into a powder that’s easier than viral systems to transport, store, and administer at different doses.

In findings published in Nature Nanotechnology [1], researchers, led by Shaoqin Gong and Krishanu Saha, University of Wisconsin-Madison, developed the nanocapsules with specific design criteria in mind. They would need to be extremely small, about the size of a small virus, for easy entry into cells. Their surface would need to be adaptable for targeting different cell types. They also had to be highly stable in the bloodstream and yet easily degraded to release their contents once inside a cell.

After much hard work in the lab, they created their prototype. It features a thin polymer shell that’s easily decorated with peptides or other ingredients to target the nanocapsule to a predetermined cell type.

At just 25 nanometers in diameter, each nanocapsule still has room to carry cargo. That cargo includes a single CRISPR/Cas9 scissor-like enzyme for snipping DNA and a guide RNA that directs it to the right spot in the genome for editing.

In the bloodstream, the nanocapsules remain fully intact. But, once inside a cell, their polymer shells quickly disintegrate and release the gene-editing payload. How is this possible? The crosslinking molecules that hold the polymer together immediately degrade in the presence of another molecule, called glutathione, which is found at high levels inside cells.

The studies showed that human cells grown in the lab readily engulf and take the gene-editing nanocapsules into bubble-like endosomes. Their gene-editing contents are then released into the cytoplasm where they can begin making their way to a cell’s nucleus within a few hours.

Further study in lab dishes showed that nanocapsule delivery of CRISPR led to precise gene editing of up to about 80 percent of human cells with little sign of toxicity. The gene-editing nanocapsules also retained their potency even after they were freeze-dried and reconstituted.

But would the nanocapsules work in a living system? To find out, the researchers turned to mice, targeting their nanocapsules to skeletal muscle and tissue in the retina at the back of eye. Their studies showed that nanocapsules injected into muscle or the tight subretinal space led to efficient gene editing. In the eye, the nanocapsules worked especially well in editing retinal cells when they were decorated with a chemical ingredient known to bind an important retinal protein.

Based on their initial results, the researchers anticipate that their delivery system could reach most cells and tissues for virtually any gene-editing application. In fact, they are now exploring the potential of their nanocapsules for editing genes within brain tissue.

I’m also pleased to note that Gong and Saha’s team is part of a nationwide consortium on genome editing supported by NIH’s recently launched Somatic Cell Genome Editing program. This program is dedicated to translating breakthroughs in gene editing into treatments for as many genetic diseases as possible. So, we can all look forward to many more advances like this one.

Reference:

[1] A biodegradable nanocapsule delivers a Cas9 ribonucleoprotein complex for in vivo genome editing. Chen G, Abdeen AA, Wang Y, Shahi PK, Robertson S, Xie R, Suzuki M, Pattnaik BR, Saha K, Gong S. Nat Nanotechnol. 2019 Sep 9.

Links:

Somatic Cell Genome Editing (NIH)

Saha Lab (University of Wisconsin-Madison)

Shaoqin (Sarah) Gong (University of Wisconsin-Madison)

NIH Support: National Eye Institute; National Institute of General Medical Sciences; National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; Common Fund

The Amazing Brain: Making Up for Lost Vision

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Recently, I’ve highlighted just a few of the many amazing advances coming out of the NIH-led Brain Research through Advancing Innovative Neurotechnologies® (BRAIN) Initiative. And for our grand finale, I’d like to share a cool video that reveals how this revolutionary effort to map the human brain is opening up potential plans to help people with disabilities, such as vision loss, that were once unimaginable.

This video, produced by Jordi Chanovas and narrated by Stephen Macknik, State University of New York Downstate Health Sciences University, Brooklyn, outlines a new strategy aimed at restoring loss of central vision in people with age-related macular degeneration (AMD), a leading cause of vision loss among people age 50 and older. The researchers’ ultimate goal is to give such people the ability to see the faces of their loved ones or possibly even read again.

In the innovative approach you see here, neuroscientists aren’t even trying to repair the part of the eye destroyed by AMD: the light-sensitive retina. Instead, they are attempting to recreate the light-recording function of the retina within the brain itself.

How is that possible? Normally, the retina streams visual information continuously to the brain’s primary visual cortex, which receives the information and processes it into the vision that allows you to read these words. In folks with AMD-related vision loss, even though many cells in the center of the retina have stopped streaming, the primary visual cortex remains fully functional to receive and process visual information.

About five years ago, Macknik and his collaborator Susana Martinez-Conde, also at Downstate, wondered whether it might be possible to circumvent the eyes and stream an alternative source of visual information to the brain’s primary visual cortex, thereby restoring vision in people with AMD. They sketched out some possibilities and settled on an innovative system that they call OBServ.

Among the vital components of this experimental system are tiny, implantable neuro-prosthetic recording devices. Created in the Macknik and Martinez-Conde labs, this 1-centimeter device is powered by induction coils similar to those in the cochlear implants used to help people with profound hearing loss. The researchers propose to surgically implant two of these devices in the rear of the brain, where they will orchestrate the visual process.

For technical reasons, the restoration of central vision will likely be partial, with the window of vision spanning only about the size of one-third of an adult thumbnail held at arm’s length. But researchers think that would be enough central vision for people with AMD to regain some of their lost independence.

As demonstrated in this video from the BRAIN Initiative’s “Show Us Your Brain!” contest, here’s how researchers envision the system would ultimately work:

• A person with vision loss puts on a specially designed set of glasses. Each lens contains two cameras: one to record visual information in the person’s field of vision; the other to track that person’s eye movements enabled by residual peripheral vision.

• The eyeglass cameras wirelessly stream the visual information they have recorded to two neuro-prosthetic devices implanted in the rear of the brain.

• The neuro-prosthetic devices process and project this information onto a specific set of excitatory neurons in the brain’s hard-wired visual pathway. Researchers have previously used genetic engineering to turn these neurons into surrogate photoreceptor cells, which function much like those in the eye’s retina.

• The surrogate photoreceptor cells in the brain relay visual information to the primary visual cortex for processing.

• All the while, the neuro-prosthetic devices perform quality control of the visual signals, calibrating them to optimize their contrast and clarity.

While this might sound like the stuff of science-fiction (and this actual application still lies several years in the future), the OBServ project is now actually conceivable thanks to decades of advances in the fields of neuroscience, vision, bioengineering, and bioinformatics research. All this hard work has made the primary visual cortex, with its switchboard-like wiring system, among the brain’s best-understood regions.

OBServ also has implications that extend far beyond vision loss. This project provides hope that once other parts of the brain are fully mapped, it may be possible to design equally innovative systems to help make life easier for people with other disabilities and conditions.

Links:

Age-Related Macular Degeneration (National Eye Institute/NIH)

Macknik Lab (SUNY Downstate Health Sciences University, Brooklyn)

Martinez-Conde Laboratory (SUNY Downstate Health Sciences University)

Show Us Your Brain! (BRAIN Initiative/NIH)

Brain Research through Advancing Innovative Neurotechnologies® (BRAIN) Initiative (NIH)

NIH Support: BRAIN Initiative

‘Nanoantennae’ Make Infrared Vision Possible

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Credit: Ma et al. Cell, 2019

Infrared vision often brings to mind night-vision goggles that allow soldiers to see in the dark, like you might have seen in the movie Zero Dark Thirty. But those bulky goggles may not be needed one day to scope out enemy territory or just the usual things that go bump in the night. In a dramatic advance that brings together material science and the mammalian vision system, researchers have just shown that specialized lab-made nanoparticles applied to the retina, the thin tissue lining the back of the eye, can extend natural vision to see in infrared light.

The researchers showed in mouse studies that their specially crafted nanoparticles bind to the retina’s light-sensing cells, where they act like “nanoantennae” for the animals to see and recognize shapes in infrared—day or night—for at least 10 weeks. Even better, the mice maintained their normal vision the whole time and showed no adverse health effects. In fact, some of the mice are still alive and well in the lab, although their ability to see in infrared may have worn off.

When light enters the eyes of mice, humans, or any mammal, light-sensing cells in the retina absorb wavelengths within the range of visible light. (That’s roughly from 400 to 700 nanometers.) While visible light includes all the colors of the rainbow, it actually accounts for only a fraction of the full electromagnetic spectrum. Left out are the longer wavelengths of infrared light. That makes infrared light invisible to the naked eye.

In the study reported in the journal Cell, an international research team including Gang Han, University of Massachusetts Medical School, Worcester, wanted to find a way for mammalian light-sensing cells to absorb and respond to the longer wavelengths of infrared [1]. It turns out Han’s team had just the thing to do it.

His NIH-funded team was already working on the nanoparticles now under study for application in a field called optogenetics—the use of light to control living brain cells [2]. Optogenetics normally involves the stimulation of genetically modified brain cells with blue light. The trouble is that blue light doesn’t penetrate brain tissue well.

That’s where Han’s so-called upconversion nanoparticles (UCNPs) came in. They attempt to get around the normal limitations of optogenetic tools by incorporating certain rare earth metals. Those metals have a natural ability to absorb lower energy infrared light and convert it into higher energy visible light (hence the term upconversion).

But could those UCNPs also serve as miniature antennae in the eye, receiving infrared light and emitting readily detected visible light? To find out in mouse studies, the researchers injected a dilute solution containing UCNPs into the back of eye. Such sub-retinal injections are used routinely by ophthalmologists to treat people with various eye problems.

These UCNPs were modified with a protein that allowed them to stick to light-sensing cells. Because of the way that UCNPs absorb and emit wavelengths of light energy, they should to stick to the light-sensing cells and make otherwise invisible infrared light visible as green light.

Their hunch proved correct, as mice treated with the UCNP solution began seeing in infrared! How could the researchers tell? First, they shined infrared light into the eyes of the mice. Their pupils constricted in response just as they would with visible light. Then the treated mice aced a series of maneuvers in the dark that their untreated counterparts couldn’t manage. The treated animals also could rely on infrared signals to make out shapes.

The research is not only fascinating, but its findings may also have a wide range of intriguing applications. One could imagine taking advantage of the technology for use in hiding encrypted messages in infrared or enabling people to acquire a temporary, built-in ability to see in complete darkness.

With some tweaks and continued research to confirm the safety of these nanoparticles, the system might also find use in medicine. For instance, the nanoparticles could potentially improve vision in those who can’t see certain colors. While such infrared vision technologies will take time to become more widely available, it’s a great example of how one area of science can cross-fertilize another.

References:

[1] Mammalian Near-Infrared Image Vision through Injectable and Self-Powered Retinal Nanoantennae. Ma Y, Bao J, Zhang Y, Li Z, Zhou X, Wan C, Huang L, Zhao Y, Han G, Xue T. Cell. 2019 Feb 27. [Epub ahead of print]

[2] Near-Infrared-Light Activatable Nanoparticles for Deep-Tissue-Penetrating Wireless Optogenetics. Yu N, Huang L, Zhou Y, Xue T, Chen Z, Han G. Adv Healthc Mater. 2019 Jan 11:e1801132.

Links:

Diagram of the Eye (National Eye Institute/NIH)

Infrared Waves (NASA)

Visible Light (NASA)

Han Lab (University of Massachusetts, Worcester)

NIH Support: National Institute of Mental Health; National Institute of General Medical Sciences

Studying Color Vision in a Dish

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Credit: Eldred et al., Science

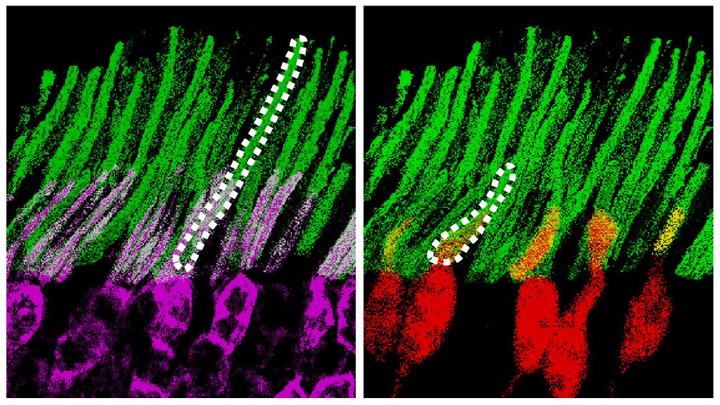

Researchers can now grow miniature versions of the human retina—the light-sensitive tissue at the back of the eye—right in a lab dish. While most “retina-in-a-dish” research is focused on finding cures for potentially blinding diseases, these organoids are also providing new insights into color vision.

Our ability to view the world in all of its rich and varied colors starts with the retina’s light-absorbing cone cells. In this image of a retinal organoid, you see cone cells (blue and green). Those labelled with blue produce a visual pigment that allows us to see the color blue, while those labelled green make visual pigments that let us see green or red. The cells that are labeled with red show the highly sensitive rod cells, which aren’t involved in color vision, but are very important for detecting motion and seeing at night.

A Ray of Molecular Beauty from Cryo-EM

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Credit: Subramaniam Lab, National Cancer Institute, NIH

Walk into a dark room, and it takes a minute to make out the objects, from the wallet on the table to the sleeping dog on the floor. But after a few seconds, our eyes are able to adjust and see in the near-dark, thanks to a protein called rhodopsin found at the surface of certain specialized cells in the retina, the thin, vision-initiating tissue that lines the back of the eye.

This illustration shows light-activating rhodopsin (orange). The light photons cause the activated form of rhodopsin to bind to its protein partner, transducin, made up of three subunits (green, yellow, and purple). The binding amplifies the visual signal, which then streams onward through the optic nerve for further processing in the brain—and the ability to avoid tripping over the dog.

Creative Minds: Reprogramming the Brain

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

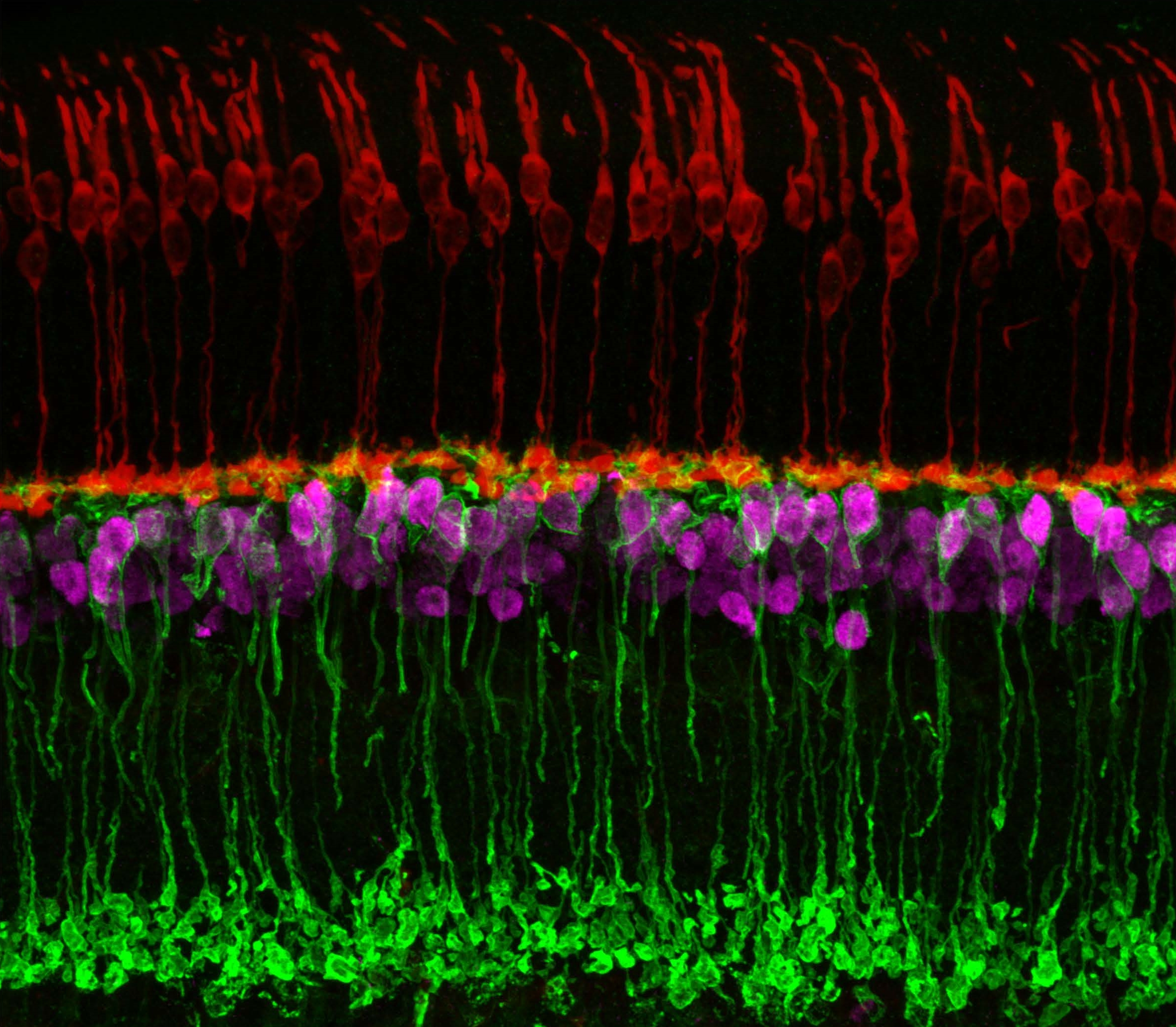

Caption: Neuronal circuits in the mouse retina. Cone photoreceptors (red) enable color vision; bipolar neurons (magenta) relay information further along the circuit; and a subtype of bipolar neuron (green) helps process signals sensed by other photoreceptors in dim light.

Credit: Brian Liu and Melanie Samuel, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston.

When most people think of reprogramming something, they probably think of writing code for a computer or typing commands into their smartphone. Melanie Samuel thinks of brain circuits, the networks of interconnected neurons that allow different parts of the brain to work together in processing information.

Samuel, a researcher at Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, wants to learn to reprogram the connections, or synapses, of brain circuits that function less well in aging and disease and limit our memory and ability to learn. She has received a 2016 NIH Director’s New Innovator Award to decipher the molecular cues that encourage the repair of damaged synapses or enable neurons to form new connections with other neurons. Because extensive synapse loss is central to most degenerative brain diseases, Samuel’s reprogramming efforts could help point the way to preventing or correcting wiring defects before they advance to serious and potentially irreversible cognitive problems.

Next Page