age-related macular degeneration

Finding Better Ways to Image the Retina

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Every day, all around the world, eye care professionals are busy performing dilated eye exams. By looking through a patient’s widened pupil, they can view the retina—the postage stamp-sized tissue lining the back of the inner eye—and look for irregularities that may signal the development of vision loss.

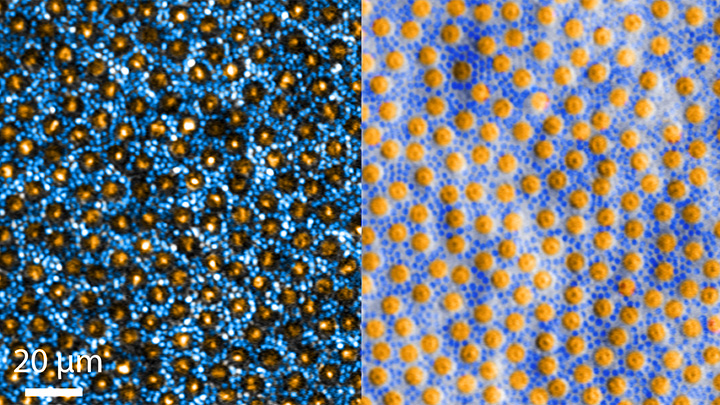

The great news is that, thanks to research, retinal imaging just keeps getting better and better. The images above, which show the same cells viewed with two different microscopic techniques, provide good examples of how tweaking existing approaches can significantly improve our ability to visualize the retina’s two types of light-sensitive neurons: rod and cone cells.

Specifically, these images show an area of the outer retina, which is the part of the tissue that’s observed during a dilated eye exam. Thanks to colorization and other techniques, a viewer can readily distinguish between the light-sensing, color-detecting cone cells (orange) and the much smaller, lowlight-sensing rod cells (blue).

These high-res images come from Johnny Tam, a researcher with NIH’s National Eye Institute. Working with Alfredo Dubra, Stanford University, Palo Alto, CA, Tam and his team figured out how to limit light distortion of the rod cells. The key was illuminating the eye using less light, provided as a halo instead of the usual solid, circular beam.

But the researchers’ solution hit a temporary snag when the halo reflected from the rods and cones created another undesirable ring of light. To block it out, Tam’s team introduced a tiny pinhole, called a sub-Airy disk. Along with use of adaptive optics technology [1] to correct for other distortions of light, the scientists were excited to see such a clear view of individual rods and cones. They published their findings recently in the journal Optica [2]

The resolution produced using these techniques is so much improved (33 percent better than with current methods) that it’s even possible to visualize the tiny inner segments of both rods and cones. In the cones, for example, these inner segments help direct light coming into the eye to other, photosensitive parts that absorb single photons of light. The light is then converted into electrical signals that stream to the brain’s visual centers in the occipital cortex, which makes it possible for us to experience vision.

Tam and team are currently working with physician-scientists in the NIH Clinical Center to image the retinas of people with a variety of retinal diseases, including age-related macular degeneration (AMD), a leading cause of vision loss in older adults. These research studies are ongoing, but offer hopeful possibilities for safe and non-intrusive monitoring of individual rods and cones over time, as well as across disease types. That’s obviously good news for patients. Plus it will help scientists understand how a rod or cone cell stops working, as well as more precisely test the effects of gene therapy and other experimental treatments aimed at restoring vision.

References:

[1] Noninvasive imaging of the human rod photoreceptor mosaic using a confocal adaptive optics scanning ophthalmoscope. Dubra A, Sulai Y, Norris JL, Cooper RF, Dubis AM, Williams DR, Carroll J. Biomed Opt Express. 2011 Jul 1;2(7):1864-76.

[1] In-vivo sub-diffraction adaptive optics imaging of photoreceptors in the human eye with annular pupil illumination and sub-Airy detection. Rongwen L, Aguilera N, Liu T, Liu J, Giannini JP, Li J, Bower AJ, Dubra A, Tam J. Optica 2021 8, 333-343. https://doi.org/10.1364/OPTICA.414206

Links:

Get a Dilated Eye Exam (National Eye Institute/NIH)

How the Eyes Work (NEI)

Eye Health Data and Statistics (NEI)

Tam Lab (NEI)

Dubra Lab (Stanford University, Palo Alto, CA)

NIH Support: National Eye Institute

Share this:

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Telegram (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window)

- Click to print (Opens in new window)

Posted In: Snapshots of Life

Tags: adaptive optics techology, age-related macular degeneration, AMD, cone cells, cones, confocal adaptive optics scanning, dilated eye exam, eye, imaging, neurons, occipital cortex, photoreceptor cells, retina, retinal diseases, retinal imaging, rod cell, rods, sub-Airy disk, vision, vision loss, visual cortex

Moving Closer to a Stem Cell-Based Treatment for AMD

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

In recent years, researchers have figured out how to take a person’s skin or blood cells and turn them into induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) that offer tremendous potential for regenerative medicine. Still, it’s been a challenge to devise safe and effective ways to move this discovery from the lab into the clinic. That’s why I’m pleased to highlight progress toward using iPSC technology to treat a major cause of vision loss: age-related macular degeneration (AMD).

In the new work, researchers from NIH’s National Eye Institute developed iPSCs from blood-forming stem cells isolated from blood donated by people with advanced AMD [1]. Next, these iPSCs were exposed to a variety of growth factors and placed on supportive scaffold that encouraged them to develop into healthy retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) tissue, which nurtures the light-sensing cells in the eye’s retina. The researchers went on to show that their lab-grown RPE patch could be transplanted safely into animal models of AMD, preventing blindness in the animals.

This preclinical work will now serve as the foundation for a safety trial of iPSC-derived RPE transplants in 12 human volunteers who have already suffered vision loss due to the more common “dry” form of AMD, for which there is currently no approved treatment. If all goes well, the NIH-led trial may begin enrolling patients as soon as this year.

Risk factors for AMD include a combination of genetic and environmental factors, including age and smoking. Currently, more than 2 million Americans have vision-threatening AMD, with millions more having early signs of the disease [2].

AMD involves progressive damage to the macula, an area of the retina about the size of a pinhead, made up of millions of light-sensing cells that generate our sharp, central vision. Though the exact causes of AMD are unknown, RPE cells early on become inflamed and lose their ability to clear away debris from the retina. This leads to more inflammation and progressive cell death.

As RPE cells are lost during the “dry” phase of the disease, light-sensing cells in the macula also start to die and reduce central vision. In some people, abnormal, leaky blood vessels will form near the macula, called “wet” AMD, spilling fluid and blood under the retina and causing significant vision loss. “Wet” AMD has approved treatments. “Dry” AMD does not.

But, advances in iPSC technology have brought hope that it might one day be possible to shore up degenerating RPE in those with dry AMD, halting the death of light-sensing cells and vision loss. In fact, preliminary studies conducted in Japan explored ways to deliver replacement RPE to the retina [3]. Though progress was made, those studies highlighted the need for more reliable ways to produce replacement RPE from a patient’s own cells. The Japanese program also raised concerns that iPSCs derived from people with AMD might be prone to cancer-causing genomic changes.

With these challenges in mind, the NEI team led by Kapil Bharti and Ruchi Sharma have designed a more robust process to produce RPE tissue suitable for testing in people. As described in Science Translational Medicine, they’ve come up with a three-step process.

Rather than using fibroblast cells from skin as others had done, Bharti and Sharma’s team started with blood-forming stem cells from three AMD patients. They reprogrammed those cells into “banks” of iPSCs containing multiple different clones, carefully screening them to ensure that they were free of potentially cancer-causing changes.

Next, those iPSCs were exposed to a special blend of growth factors to transform them into RPE tissue. That recipe has been pursued by other groups for a while, but needed to be particularly precise for this human application. In order for the tissue to function properly in the retina, the cells must assemble into a uniform sheet, just one-cell thick, and align facing in the same direction.

So, the researchers developed a specially designed scaffold made of biodegradable polymer nanofibers. That scaffold helps to ensure that the cells orient themselves correctly, while also lending strength for surgical transplantation. By spreading a single layer of iPSC-derived RPE progenitors onto their scaffolds and treating it with just the right growth factors, the researchers showed they could produce an RPE patch ready for the clinic in about 10 weeks.

To test the viability of the RPE patch, the researchers first transplanted a tiny version (containing about 2,500 RPE cells) into the eyes of a rat with a compromised immune system, which enables human cells to survive. By 10 weeks after surgery, the human replacement tissue had integrated into the animals’ retinas with no signs of toxicity.

Next, the researchers tested a larger RPE patch (containing 70,000 cells) in pigs with an AMD-like condition. This patch is the same size the researchers ultimately would expect to use in people. Ten weeks after surgery, the RPE patch had integrated into the animals’ eyes, where it protected the light-sensing cells that are so critical for vision, preventing blindness.

These results provide encouraging evidence that the iPSC approach to treating dry AMD should be both safe and effective. But only a well-designed human clinical trial, with all the appropriate prior oversights to be sure the benefits justify the risks, will prove whether or not this bold approach might be the solution to blindness faced by millions of people in the future.

As the U.S. population ages, the number of people with advanced AMD is expected to rise. With continued progress in treatment and prevention, including iPSC technology and many other promising approaches, the hope is that more people with AMD will retain healthy vision for a lifetime.

References:

[1] Clinical-grade stem cell-derived retinal pigment epithelium patch rescues retinal degeneration in rodents and pigs. Sharma R, Khristov V, Rising A, Jha BS, Dejene R, Hotaling N, Li Y, Stoddard J, Stankewicz C, Wan Q, Zhang C, Campos MM, Miyagishima KJ, McGaughey D, Villasmil R, Mattapallil M, Stanzel B, Qian H, Wong W, Chase L, Charles S, McGill T, Miller S, Maminishkis A, Amaral J, Bharti K. Sci Transl Med. 2019 Jan 16;11(475).

[2] Age-Related Macular Degeneration, National Eye Institute.

[3] Autologous Induced Stem-Cell-Derived Retinal Cells for Macular Degeneration. Mandai M, Watanabe A, Kurimoto Y, Hirami Y, Takasu N, Ogawa S, Yamanaka S, Takahashi M, et al. N Engl J Med. 2017 Mar 16;376(11):1038-1046.

Links:

Facts About Age-Related Macular Degeneration (National Eye Institute/NIH)

Stem Cell-Based Treatment Used to Prevent Blindness in Animal Models of Retinal Degeneration (National Eye Institute/NIH)

Kapil Bharti (NEI)

NIH Support: National Eye Institute; Common Fund

Share this:

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Telegram (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window)

- Click to print (Opens in new window)

Posted In: News

Tags: age-related macular degeneration, aging, AMD, blindness, central vision, dry AMD, eyes, eyesight, induced Pluripotent Stem cells, iPSCs, macular degeneration, ophthalmology, retina, retinal pigment epithelial cells, RPE, RPE patch, stem cell therapy, stem cells, tissue engineering, vision, vision loss

Regenerative Medicine: The Promise and Peril

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Caption: Scanning electron micrograph of iPSC-derived retinal pigment epithelial cells growing on a nanofiber scaffold (blue).

Credit: Sheldon Miller, Arvydas Maminishkis, Robert Fariss, and Kapil Bharti, National Eye Institute/NIH

Stem cells derived from a person’s own body have the potential to replace tissue damaged by a wide array of diseases. Now, two reports published in the New England Journal of Medicine highlight the promise—and the peril—of this rapidly advancing area of regenerative medicine. Both groups took aim at the same disorder: age-related macular degeneration (AMD), a common, progressive form of vision loss. Unfortunately for several patients, the results couldn’t have been more different.

In the first case, researchers in Japan took cells from the skin of a female volunteer with AMD and used them to create induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) in the lab. Those iPSCs were coaxed into differentiating into cells that closely resemble those found near the macula, a tiny area in the center of the eye’s retina that is damaged in AMD. The lab-grown tissue, made of retinal pigment epithelial cells, was then transplanted into one of the woman’s eyes. While there was hope that there might be actual visual improvement, the main goal of this first in human clinical research project was to assess safety. The patient’s vision remained stable in the treated eye, no adverse events occurred, and the transplanted cells remained viable for more than a year.

Exciting stuff, but, as the second report shows, it is imperative that all human tests of regenerative approaches be designed and carried out with the utmost care and scientific rigor. In that instance, three elderly women with AMD each paid $5,000 to a Florida clinic to be injected in both eyes with a slurry of cells, including stem cells isolated from their own abdominal fat. The sad result? All of the women suffered severe and irreversible vision loss that left them legally or, in one case, completely blind.

Share this:

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Telegram (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window)

- Click to print (Opens in new window)

Posted In: Ethics, Health, Science

Tags: age-related macular degeneration, AMD, blindness, central vision, clinical research, dry AMD, eye disease, fat, fat cells, fovea, induced Pluripotent Stem cells, iPSCs, macula, macular degeneration, Nobel Prize, regenerative medicine, replacement tissue, retina, retinal pigment epithelial cells, RPE, stem cells, transplantation, vision, vision loss, wet AMD

Creative Minds: Reverse Engineering Vision

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

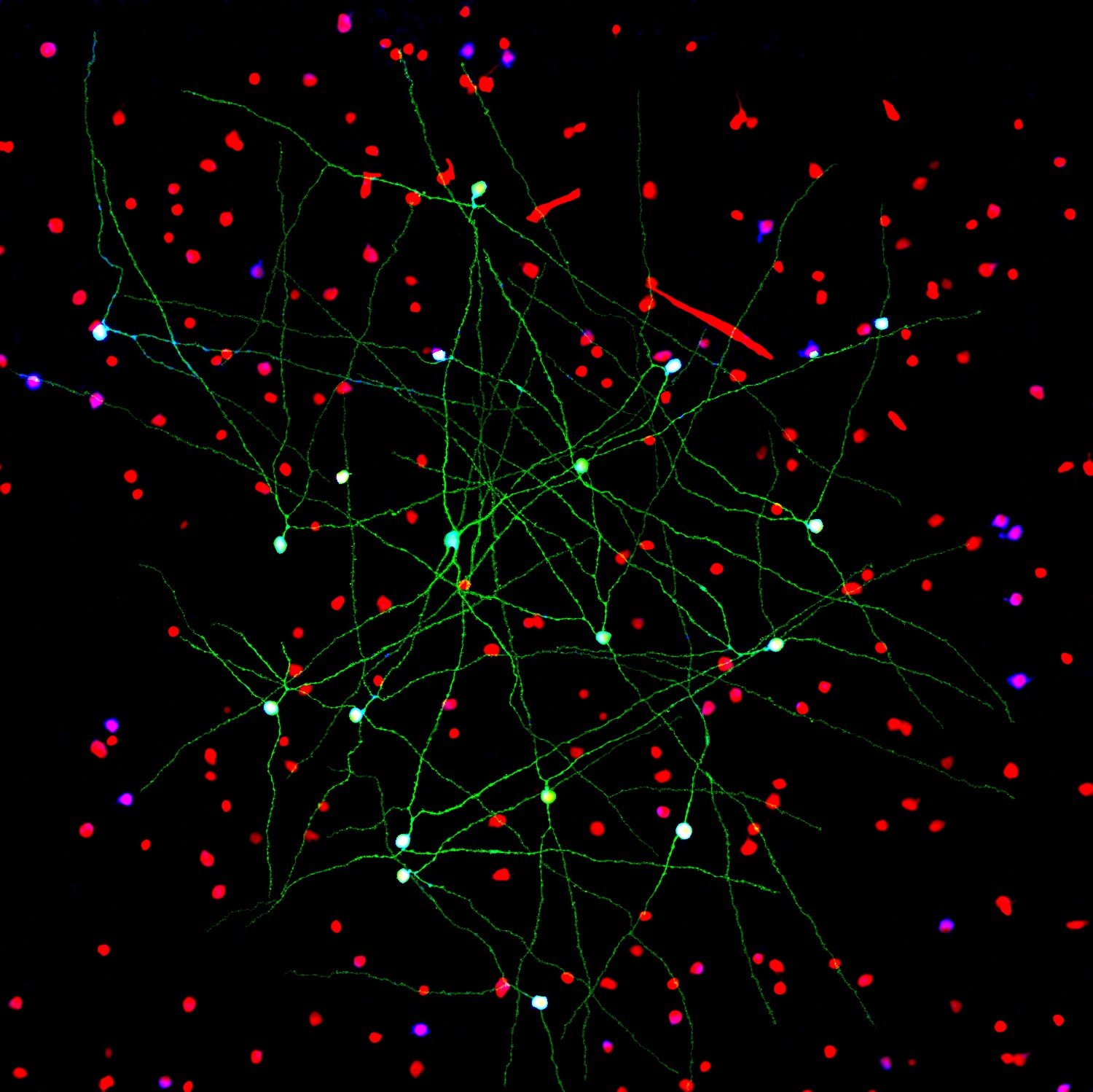

Caption: Networks of neurons in the mouse retina. Green cells form a special electrically coupled network; red cells express a distinctive fluorescent marker to distinguish them from other cells; blue cells are tagged with an antibody against an enzyme that makes nitric oxide, important in retinal signaling. Such images help to identify retinal cell types, their signaling molecules, and their patterns of connectivity.

Credit: Jason Jacoby and Gregory Schwartz, Northwestern University

For Gregory Schwartz, working in total darkness has its benefits. Only in the pitch black can Schwartz isolate resting neurons from the eye’s retina and stimulate them with their natural input—light—to get them to fire electrical signals. Such signals not only provide a readout of the intrinsic properties of each neuron, but information that enables the vision researcher to deduce how it functions and forges connections with other neurons.

The retina is the light-sensitive neural tissue that lines the back of the eye. Although only about the size of a postage stamp, each of our retinas contains an estimated 130 million cells and more than 100 distinct cell types. These cells are organized into multiple information-processing layers that work together to absorb light and translate it into electrical signals that stream via the optic nerve to the appropriate visual center in the brain. Like other parts of the eye, the retina can break down, and retinal diseases, including age-related macular degeneration, retinitis pigmentosa, and diabetic retinopathy, continue to be leading causes of vision loss and blindness worldwide.

In his lab at Northwestern University’s Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago, Schwartz performs basic research that is part of a much larger effort among vision researchers to assemble a parts list that accounts for all of the cell types needed to make a retina. Once Schwartz and others get closer to wrapping up this list, the next step will be to work out the details of the internal wiring of the retina to understand better how it generates visual signals. It’s the kind of information that holds the key for detecting retinal diseases earlier and more precisely, fixing miswired circuits that affect vision, and perhaps even one day creating an improved prosthetic retina.

Share this:

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Telegram (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window)

- Click to print (Opens in new window)

Tags: 2015 NIH Director’s New Innovator Award, age-related macular degeneration, brain, BRAIN Initiative, cerebral cortex, computational biology, computational neuroscience, connectivity matrix, diabetic retinopathy, eye, ganglion cells, macula, neurons, neuroscience, retina, retinal diseases, retinitis pigmentosa, reverse engineering, vision, vision loss, visual orientation

Snapshots of Life: Behold the Beauty of the Eye

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

The eye is a complex marvel of nature. In fact, there are some 70 to 80 kinds of cells in the mammalian retina. This image beautifully illuminates the eye’s complexity, on a cellular level—showing how these cells are arranged and wired together to facilitate sight.

“Reading” the image from left to right, we first find the muscle cells, in peach, that move the eye in its socket. The green layer, next, is the sclera—the white part of the eye. The spongy-looking layers that follow provide blood to the retina. The thin layer of yellow is the retinal pigment epithelium. The photoreceptors, in shades of pink, detect photons and transmit the information to the next layer down: the bipolar and horizontal cells (purple). From the bipolar cells, information flows to the amacrine and ganglion cells (blue, green, and turquoise) and then out of the retina via the optic nerve (the white plume that seems to billow out across the upper-right side of the eye), which transmits data to the brain for processing.

Share this:

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Telegram (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window)

- Click to print (Opens in new window)