regenerative medicine

Understanding Neuronal Diversity in the Spinal Cord

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

The spinal cord, as a key part of our body’s central nervous system, contains millions of neurons that actively convey sensory and motor (movement) information to and from the brain. Scientists have long sorted these spinal neurons into what they call “cardinal” classes, a classification system based primarily on the developmental origin of each nerve cell. Now, by taking advantage of the power of single-cell genetic analysis, they’re finding that spinal neurons are more diverse than once thought.

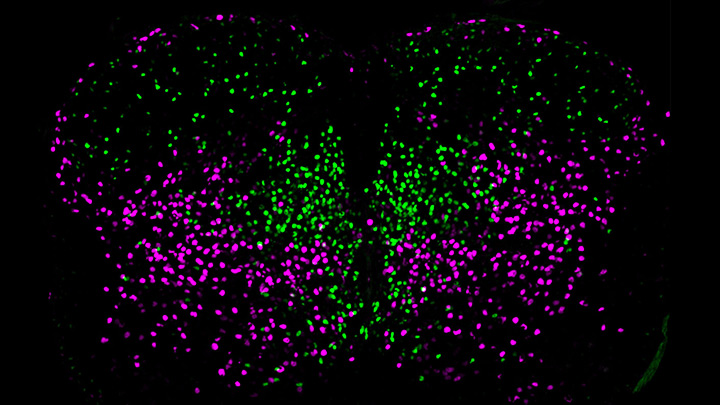

This image helps to visualize the story. Each dot represents the nucleus of a spinal neuron in a mouse; humans have a very similar arrangement. Most of these neurons are involved in the regulation of motor control, but they also differ in important ways. Some are involved in local connections (green), such as those that signal outward to a limb and prompt us to pull away reflexively when we touch painful stimuli, such as a hot frying pan. Others are involved in long-range connections (magenta), relaying commands across spinal segments and even upward to the brain. These enable us, for example, to swing our arms while running to help maintain balance.

It turns out that these two types of spinal neurons also have distinctive genetic signatures. That’s why researchers could label them here in different colors and tell them apart. Being able to distinguish more precisely among spinal neurons will prove useful in identifying precisely which ones are affected by a spinal cord injury or neurodegenerative disease, key information in learning to engineer new tissue to heal the damage.

This image comes from a study, published recently in the journal Science, conducted by an NIH-supported team led by Samuel Pfaff, Salk Institute for Biological Studies, La Jolla, CA. Pfaff and his colleagues, including Peter Osseward and Marito Hayashi, realized that the various classes and subtypes of neurons in our spines arose over the course of evolutionary time. They reasoned that the most-primitive original neurons would have gradually evolved subtypes with more specialized and diverse capabilities. They thought they could infer this evolutionary history by looking for conserved and then distinct, specialized gene-expression signatures in the different neural subtypes.

The researchers turned to single-cell RNA sequencing technologies to look for important similarities and differences in the genes expressed in nearly 7,000 mouse spinal neurons. They then used this vast collection of genomic data to group the neurons into closely related clusters, in much the same way that scientists might group related organisms into an evolutionary family tree based on careful study of their DNA.

The first major gene expression pattern they saw divided the spinal neurons into two types: sensory-related and motor-related. This suggested to them that one of the first steps in spinal cord evolution may have been a division of labor of spinal neurons into those two fundamentally important roles.

Further analyses divided the sensory-related neurons into excitatory neurons, which make neurons more likely to fire; and inhibitory neurons, which dampen neural firing. Then, the researchers zoomed in on motor-related neurons and found something unexpected. They discovered the cells fell into two distinct molecular groups based on whether they had long-range or short-range connections in the body. Researches were even more surprised when further study showed that those distinct connectivity signatures were shared across cardinal classes.

All of this means that, while previously scientists had to use many different genetic tags to narrow in on a particular type of neuron, they can now do it with just two: a previously known tag for cardinal class and the newly discovered genetic tag for long-range vs. short-range connections.

Not only is this newfound ability a great boon to basic neuroscientists, it also could prove useful for translational and clinical researchers trying to determine which specific neurons are affected by a spinal injury or disease. Eventually, it may even point the way to strategies for regrowing just the right set of neurons to repair serious neurologic problems. It’s a vivid reminder that fundamental discoveries, such as this one, often can lead to unexpected and important breakthroughs with potential to make a real difference in people’s lives.

Reference:

[1] Conserved genetic signatures parcellate cardinal spinal neuron classes into local and projection subsets. Osseward PJ 2nd, Amin ND, Moore JD, Temple BA, Barriga BK, Bachmann LC, Beltran F Jr, Gullo M, Clark RC, Driscoll SP, Pfaff SL, Hayashi M. Science. 2021 Apr 23;372(6540):385-393.

Links:

What Are the Parts of the Nervous System? (Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development/NIH)

Spinal Cord Injury (National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke/NIH)

Samuel Pfaff (Salk Institute, La Jolla, CA)

NIH Support: National Institute of Mental Health; National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke; Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development

Replenishing the Liver’s Immune Protections

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

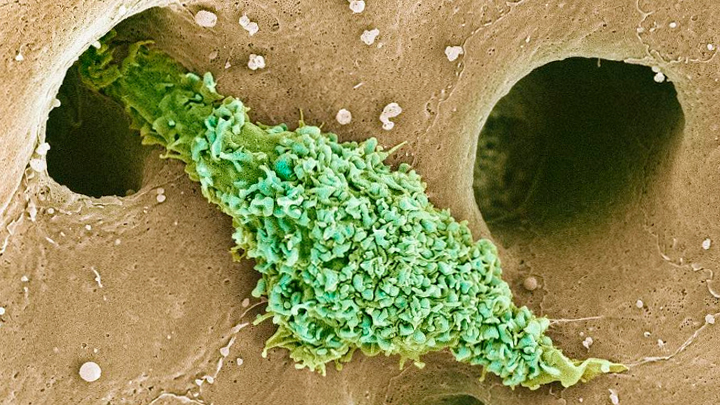

Most of our immune cells circulate throughout the bloodstream to serve as a roving security force against infection. But some immune cells don’t travel much at all and instead safeguard a specific organ or tissue. That’s what you are seeing in this electron micrograph of a type of scavenging macrophage, called a Kupffer cell (green), which resides exclusively in the liver (brown).

Normally, Kupffer cells appear in the liver during the early stages of mammalian development and stay put throughout life to protect liver cells, clean up old red blood cells, and regulate iron levels. But in their experimental system, Christopher Glass and his colleagues from University of California, San Diego, removed all original Kupffer cells from a young mouse to see if this would allow signals from the liver that encourage the development of new Kupffer cells.

The NIH-funded researchers succeeded in setting up the right conditions to spur a heavy influx of circulating precursor immune cells, called monocytes, into the liver, and then prompted those monocytes to turn into the replacement Kupffer cells. In a recent study in the journal Immunity, the team details the specific genomic changes required for the monocytes to differentiate into Kupffer cells [1]. This information will help advance the study of Kupffer cells and their role in many liver diseases, including nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), which affects an estimated 3 to 12 percent of U.S. adults [2].

The new work also has broad implications for immunology research because it provides additional evidence that circulating monocytes contain genomic instructions that, when activated in the right way by nearby cells or other factors, can prompt the monocytes to develop into various, specialized types of scavenging macrophages. For example, in the mouse system, Glass’s team found that the endothelial cells lining the liver’s blood vessels, which is where Kupffer cells hang out, emit biochemical distress signals when their immune neighbors disappear.

While more details need to be worked out, this study is another excellent example of how basic research, including the ability to query single cells about their gene expression programs, is generating fundamental knowledge about the nature and behavior of living systems. Such knowledge is opening new possibilities to more precise ways of treating and preventing diseases all throughout the body, including those involving Kupffer cells and the liver.

References:

[1] Liver-Derived Signals Sequentially Reprogram Myeloid Enhancers to Initiate and Maintain Kupffer Cell Identity. Sakai M, Troutman TD, Seidman JS, Ouyang Z, Spann NJ, Abe Y, Ego KM, Bruni CM, Deng Z, Schlachetzki JCM, Nott A, Bennett H, Chang J, Vu BT, Pasillas MP, Link VM, Texari L, Heinz S, Thompson BM, McDonald JG, Geissmann F3, Glass CK. Immunity. 2019 Oct 15;51(4):655-670.

[2] Recommendations for diagnosis, referral for liver biopsy, and treatment of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Spengler EK, Loomba R. Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 2015;90(9):1233–1246.

Links:

Liver Disease (National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases/NIH)

Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease & NASH (NIDDK)

Glass Laboratory (University of California, San Diego)

NIH Support: National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; National Institute of General Medical Sciences; National Cancer Institute

3D Printing a Human Heart Valve

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

It is now possible to pull up the design of a guitar on a computer screen and print out its parts on a 3D printer equipped with special metal or plastic “inks.” The same technological ingenuity is also now being applied with bioinks—printable gels containing supportive biomaterials and/or cells—to print out tissue, bone, blood vessels, and, even perhaps one day, viable organs.

While there’s a long way to go until then, a team of researchers has reached an important milestone in bioprinting collagen and other extracellular matrix proteins that undergird every tissue and organ in the body. The researchers have become so adept at it that they now can print biomaterials that mimic the structural, mechanical, and biological properties of real human tissues.

Take a look at the video. It shows a life-size human heart valve that’s been printed with their improved collagen bioink. As fluid passes through the aortic valve in a lab test, its three leaf-like flaps open and close like the real thing. All the while, the soft, flexible valve withstands the intense fluid pressure, which mimics that of blood flowing in and out of a beating heart.

The researchers, led by NIH grantee Adam Feinberg, Carnegie Mellon University, Pittsburgh, PA, did it with their latest version of a 3D bioprinting technique featured on the blog a few years ago. It’s called: Freeform Reversible Embedding of Suspended Hydrogels v.2.0. Or, just FRESH v2.0.

The FRESH system uses a bioink that consists of collagen (or other soft biomaterials) embedded in a thick slurry of gelatin microparticles and water. While a number of technical improvements have been made to FRESH v. 2.0, the big one was getting better at bioprinting collagen.

The secret is to dissolve the collagen bioink in an acid solution. When extruded into a neutral support bath, the change in pH drives the rapid assembly of collagen. The ability to extrude miniscule amounts and move the needle anywhere in 3D space enables them to produce amazingly complex, high-resolution structures, layer by layer. The porous microstructure of the printed collagen also helps for incorporating human cells. When printing is complete, the support bath easily melts away by heating to body temperature.

As described in Science, in addition to the working heart valve, the researchers have printed a small model of a heart ventricle. By combining collagen with cardiac muscle cells, they found they could actually control the organization of muscle tissue within the model heart chamber. The 3D-printed ventricles also showed synchronized muscle contractions, just like you’d expect in a living, beating human heart!

That’s not all. Using MRI images of an adult human heart as a template, the researchers created a complete organ structure including internal valves, large veins, and arteries. Based on the vessels they could see in the MRI, they printed even tinier microvessels and showed that the structure could support blood-like fluid flow.

While the researchers have focused the potential of FRESH v.2.0 printing on a human heart, in principle the technology could be used for many other organ systems. But there are still many challenges to overcome. A major one is the need to generate and incorporate billions of human cells, as would be needed to produce a transplantable human heart or other organ.

Feinberg reports more immediate applications of the technology on the horizon, however. His team is working to apply FRESH v.2.0 for producing child-sized replacement tracheas and precisely printed scaffolds for healing wounded muscle tissue.

Meanwhile, the Feinberg lab generously shares its designs with the scientific community via the NIH 3D Print Exchange. This innovative program is helping to bring more 3D scientific models online and advance the field of bioprinting. So we can expect to read about many more exciting milestones like this one from the Feinberg lab.

Reference:

[1] 3D bioprinting of collagen to rebuild components of the human heart. Lee A, Hudson AR, Shiwarski DJ, Tashman JW, Hinton TJ, Yerneni S, Bliley JM, Campbell PG, Feinberg AW. Science. 2019 Aug 2;365(6452):482-487.

Links:

Tissue Engineering and Regenerative Medicine (National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering/NIH)

Regenerative Biomaterials and Therapeutics Group (Carnegie Mellon University, Pittsburgh, PA)

FluidForm (Acton, MA)

3D Bioprinting Open Source Workshops (Carnegie Mellon)

Video: Adam Feinberg on Tissue Engineering to Treat Human Disease (YouTube)

NIH Support: National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development; Common Fund

Skin Cells Can Be Reprogrammed In Vivo

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Thousands of Americans are rushed to the hospital each day with traumatic injuries. Daniel Gallego-Perez hopes that small chips similar to the one that he’s touching with a metal stylus in this photo will one day be a part of their recovery process.

The chip, about one square centimeter in size, includes an array of tiny channels with the potential to regenerate damaged tissue in people. Gallego-Perez, a researcher at The Ohio State University Colleges of Medicine and Engineering, Columbus, has received a 2018 NIH Director’s New Innovator Award to develop the chip to reprogram skin and other cells to become other types of tissue needed for healing. The reprogrammed cells then could regenerate and restore injured neural or vascular tissue right where it’s needed.

Gallego-Perez and his Ohio State colleagues wondered if it was possible to engineer a device placed on the skin that’s capable of delivering reprogramming factors directly into cells, eliminating the need for the viral delivery vectors now used in such work. While such a goal might sound futuristic, Gallego-Perez and colleagues offered proof-of-principle last year in Nature Nanotechnology that such a chip can reprogram skin cells in mice. [1]

Here’s how it works: First, the chip’s channels are loaded with specific reprogramming factors, including DNA or proteins, and then the chip is placed on the skin. A small electrical current zaps the chip’s channels, driving reprogramming factors through cell membranes and into cells. The process, called tissue nanotransfection (TNT), is finished in milliseconds.

To see if the chips could help heal injuries, researchers used them to reprogram skin cells into vascular cells in mice. Not only did the technology regenerate blood vessels and restore blood flow to injured legs, the animals regained use of those limbs within two weeks of treatment.

The researchers then went on to show that they could use the chips to reprogram mouse skin cells into neural tissue. When proteins secreted by those reprogrammed skin cells were injected into mice with brain injuries, it helped them recover.

In the newly funded work, Gallego-Perez wants to take the approach one step further. His team will use the chip to reprogram harder-to-reach tissues within the body, including peripheral nerves and the brain. The hope is that the device will reprogram cells surrounding an injury, even including scar tissue, and “repurpose” them to encourage nerve repair and regeneration. Such an approach may help people who’ve suffered a stroke or traumatic nerve injury.

If all goes well, this TNT method could one day fill an important niche in emergency medicine. Gallego-Perez’s work is also a fine example of just one of the many amazing ideas now being pursued in the emerging field of regenerative medicine.

Reference:

[1] Topical tissue nano-transfection mediates non-viral stroma reprogramming and rescue. Gallego-Perez D, Pal D, Ghatak S, Malkoc V, Higuita-Castro N, Gnyawali S, Chang L, Liao WC, Shi J, Sinha M, Singh K, Steen E, Sunyecz A, Stewart R, Moore J, Ziebro T, Northcutt RG, Homsy M, Bertani P, Lu W, Roy S, Khanna S, Rink C, Sundaresan VB, Otero JJ, Lee LJ, Sen CK. Nat Nanotechnol. 2017 Oct;12(10):974-979.

Links:

Stroke Information (National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke/NIH)

Burns and Traumatic Injury (NIH)

Peripheral Neuropathy (National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke/NIH)

Video: Breakthrough Device Heals Organs with a Single Touch (YouTube)

Gallego-Perez Lab (The Ohio State University College of Medicine, Columbus)

Gallego-Perez Project Information (NIH RePORTER)

NIH Support: Common Fund; National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke

Regenerative Medicine: Making Blood Stem Cells in the Lab

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Caption: Arrow in first panel points to an endothelial cell induced to become hematopoietic stem cell (HSC). Second and third panels show the expansion of HSCs over time.

Credit: Raphael Lis, Weill Cornell Medicine, New York, NY

Bone marrow transplants offer a way to cure leukemia, sickle cell disease, and a variety of other life-threatening blood disorders.There are two major problems, however: One is many patients don’t have a well-matched donor to provide the marrow needed to reconstitute their blood with healthy cells. Another is even with a well-matched donor, rejection or graft versus host disease can occur, and lifelong immunosuppression may be needed.

A much more powerful option would be to develop a means for every patient to serve as their own bone marrow donor. To address this challenge, researchers have been trying to develop reliable, lab-based methods for making the vital, blood-producing component of bone marrow: hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs).

Two new studies by NIH-funded research teams bring us closer to achieving this feat. In the first study, researchers developed a biochemical “recipe” to produce HSC-like cells from human induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), which were derived from mature skin cells. In the second, researchers employed another approach to convert mature mouse endothelial cells, which line the inside of blood vessels, directly into self-renewing HSCs. When these HSCs were transplanted into mice, they fully reconstituted the animals’ blood systems with healthy red and white blood cells.

Snapshots of Life: Healing Spinal Cord Injuries

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

When someone suffers a fully severed spinal cord, it’s considered highly unlikely the injury will heal on its own. That’s because the spinal cord’s neural tissue is notorious for its inability to bridge large gaps and reconnect in ways that restore vital functions. But the image above is a hopeful sight that one day that could change.

Here, a mouse neural stem cell (blue and green) sits in a lab dish, atop a special gel containing a mat of synthetic nanofibers (purple). The cell is growing and sending out spindly appendages, called axons (green), in an attempt to re-establish connections with other nearby nerve cells.

Snapshots of Life: Wired for Nerve Regeneration

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

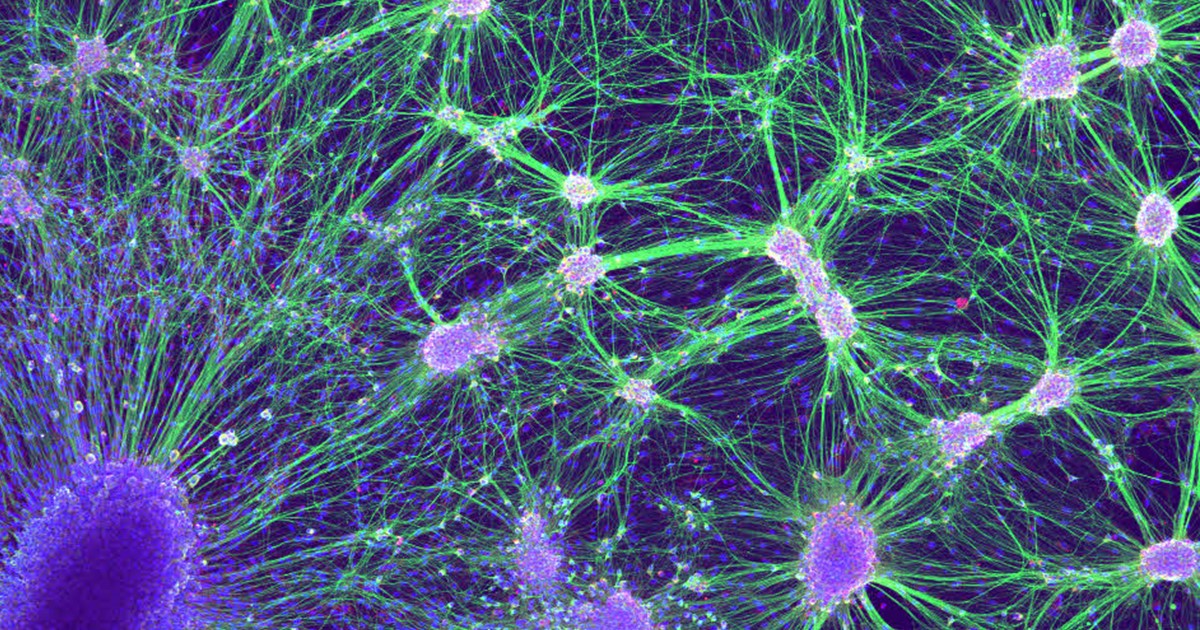

Credit: Laura Struzyna, Cullen Laboratory, Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia

Getting nerve cells to grow in the lab can be a challenge. But when it works, the result can be a thing of beauty for both science and art. What you see growing in the Petri dish shown above are nerve cells from an embryonic rat. On the bottom left is a dorsal root ganglion (dark purple), which is a cluster of sensory nerve bodies normally found just outside the spinal cord. To the right are the nuclei (light purple) and axons (green) of motor neurons, which are the nerve cells involved in forming key signaling networks.

Laura Struzyna, a graduate student in the lab of NIH grantee D. Kacy Cullen at the University of Pennsylvania’s Perelman School of Medicine, Philadelphia, is using laboratory-grown nerve cells in her efforts to learn how to bioengineer nerve grafts. The hope is this work will one day lead to grafts that can be used to treat people whose nerves have been damaged by car accidents or other traumatic injuries.

Regenerative Medicine: New Clue from Fish about Healing Spinal Cord Injuries

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

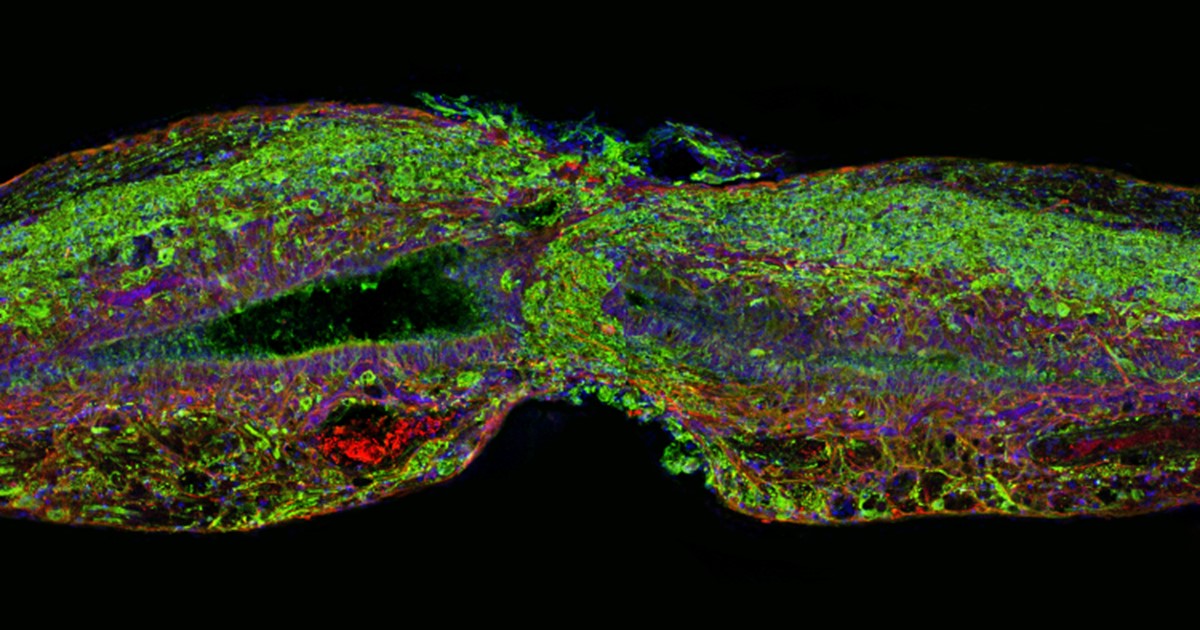

Caption: Tissue section of zebrafish spinal cord regenerating after injury. Glial cells (red) cross the gap between the severed ends first. Neuronal cells (green) soon follow. Cell nuclei are stained blue and purple.

Credit: Mayssa Mokalled and Kenneth Poss, Duke University, Durham, NC

Certain organisms have remarkable abilities to achieve self-healing, and a fascinating example is the zebrafish (Danio rerio), a species of tropical freshwater fish that’s an increasingly popular model organism for biological research. When the fish’s spinal cord is severed, something remarkable happens that doesn’t occur in humans: supportive cells in the nervous system bridge the gap, allowing new nerve tissue to restore the spinal cord to full function within weeks.

Pretty incredible, but how does this occur? NIH-funded researchers have just found an important clue. They’ve discovered that the zebrafish’s damaged cells secrete a molecule known as connective tissue growth factor a (CTGFa) that is essential in regenerating its severed spinal cord. What’s particularly encouraging to those looking for ways to help the 12,000 Americans who suffer spinal cord injuries each year is that humans also produce a form of CTGF. In fact, the researchers found that applying human CTGF near the injured site even accelerated the regenerative process in zebrafish. While this growth factor by itself is unlikely to produce significant spinal cord regeneration in human patients, the findings do offer a promising lead for researchers pursuing the next generation of regenerative therapies.

Creative Minds: Making a Miniature Colon in the Lab

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Caption: Top down view of gut tissue monolayer grown on an engineered scaffold, which guides the cells into organized crypts structures similar to the conformation of crypts in the human colon. Areas between the circles represent the flat lumenal surface.

Credit: Nancy Allbritton, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill

When Nancy Allbritton was a child in Marksville, LA, she designed and built her own rabbit hutches. She also once took apart an old TV set to investigate the cathode ray tube inside before turning the wooden frame that housed the TV into a bookcase, which, by the way, she still has. Allbritton’s natural curiosity for how things work later inspired her to earn advanced degrees in medicine, medical engineering, and medical physics, while also honing her skills in cell biology and analytical chemistry.

Now, Allbritton applies her wide-ranging research background to design cutting-edge technologies in her lab at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill. In one of her boldest challenges yet, supported by a 2015 NIH Director’s Transformative Research Award, Allbritton and a multidisciplinary team of collaborators have set out to engineer a functional model of a large intestine, or colon, on a microfabricated chip about the size of a dime.

Next Page