wound healing

Can Bioprinted Skin Substitutes Replace Traditional Grafts for Treating Burn Injuries and Other Serious Skin Wounds?

Posted on by Lawrence Tabak, D.D.S., Ph.D.

Each year in the U.S., more than 500,000 people receive treatment for burn injuries and other serious skin wounds.1 To close the most severe wounds with less scarring, doctors often must surgically remove skin from one part of a person’s body and use it to patch the injured site. However, this is an intensive process, and some burn patients with extensive skin loss do not have sufficient skin available for grafting. Scientists have been exploring ways to repair these serious skin wounds without skin graft surgery.

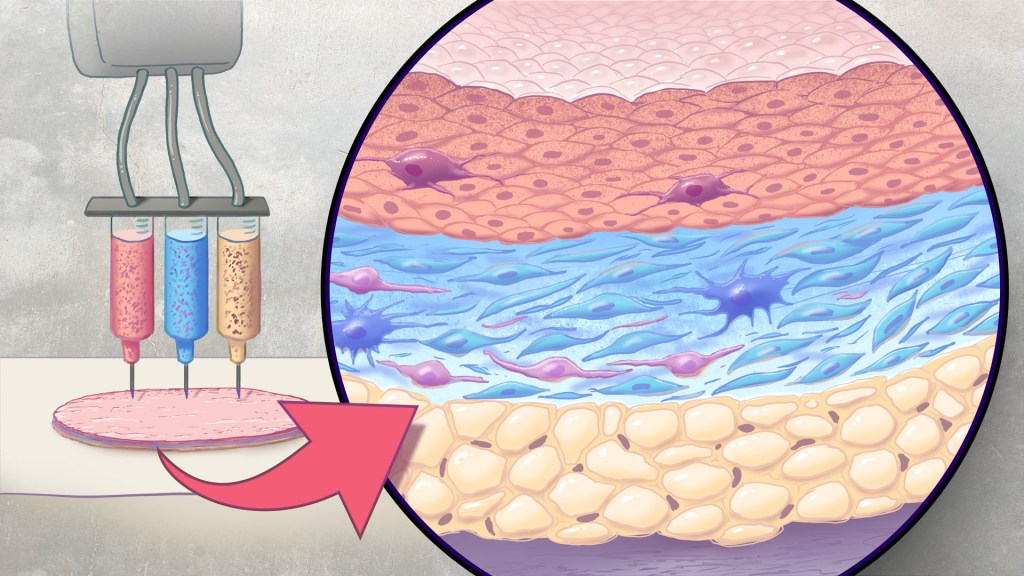

An NIH-funded team recently showed that bioprinted skin substitutes may serve as a promising alternative to traditional skin grafts in preclinical studies reported in Science Translational Medicine.2 The approach involves a portable skin bioprinter system that deposits multiple layers of skin directly into a wound. The recent findings add to evidence that bioprinting technology can successfully regenerate human-like skin to allow healing. While this approach has yet to be tested in people, it confirms that such technologies already can produce skin constructs with the complex structures and multiple cell types present in healthy human skin.

This latest work comes from a team led by Adam Jorgensen and Anthony Atala at Wake Forest School of Medicine’s Wake Forest Institute for Regenerative Medicine, Winston-Salem, NC. Members of the Atala lab and their colleagues had earlier shown it was possible to isolate two major skin cell types found in the skin’s outer (epidermis) and middle (dermis) layers from a small biopsy of healthy skin, expand the number of cells in the lab and then deliver the cells directly into an injury using a specially designed bioprinter.3 Using integrated imaging technology to scan a wound, computer software “prints” cells right into an injury, mimicking two of our skin’s three natural layers.

In the new study, Atala’s team has gone even further to construct skin substitutes that mimic the structure of human skin and that include six primary human skin cell types. They then used their bioprinter to produce skin constructs with all three layers found in healthy human skin: epidermis, dermis, and hypodermis.

To put their skin substitutes to the test, they first transplanted them into mice. Their studies showed that the bioprinted skin encouraged the rapid growth of new blood vessels and had other features of normal-looking, healthy skin. The researchers were able to confirm that their bioprinted skin implants successfully integrated into the animals’ regenerated skin to speed healing.

Studies in a pig model of wound healing added to evidence that such bioprinted implants can successfully repair full-thickness wounds, meaning those that extend through all three layers of skin. The bioprinted skin patches allowed for improved wound healing with less scarring. They also found that the bioprinted grafts encouraged activity in the skin from genes known to play important roles in wound healing.

It’s not yet clear if this approach will work as well in the clinic as it does in the lab. To make it feasible, the researchers note there’s a need for improved approaches to isolating and expanding the needed skin cell types. Nevertheless, these advances come as encouraging evidence that bioprinted skin substitutes could one day offer a promising alternative to traditional skin grafts with the capacity to help even more people with severe burns or other wounds.

References:

[1] Burn Incidence Fact Sheet. American Burn Association

[2] AM Jorgensen, et al. Multicellular bioprinted skin facilitates human-like skin architecture in vivo. Science Translational Medicine DOI: 10.1126/scitranslmed.adf7547 (2023).

[3] M Albanna, et al. In Situ Bioprinting of Autologous Skin Cells Accelerates Wound Healing of Extensive Excisional Full-Thickness Wounds. Scientific Reports DOI: 10.1038/s41598-018-38366-w (2019).

NIH Support: National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases

How to Heal Skin Without the Scars

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Most of us can point to a few unwanted scars on our bodies. Every scar tells a story, but people are spending billions of dollars each year trying to hide or get rid of them [1]. What if there was a way to get the wounds on our skin to heal without scarring in the first place?

In a recent paper in the journal Science, a team of NIH-supported researchers has taken an important step in this direction. Working with mice, the researchers deciphered some of the key chemical and physical signals that cause certain skin cells to form tough, fibrous scars while healing a wound [2]. They also discovered how to reprogram them with a topical treatment and respond to injuries more like fetal skin cells, which can patch up wounds in full, regrowing hair, glands, and accessory structures of the skin, and all without leaving a mark.

Of course, mice are not humans. Follow-up research is underway to replicate these findings in larger mammals with skin that’s tighter and more akin to ours. But if the preclinical data hold up, the researchers say they can test in future human clinical trials the anti-scarring drug used in the latest study, which has been commercially available for two decades to treat blood vessel disorders in the eye.

The work comes from Michael Longaker, Shamik Mascharak, and colleagues, Stanford Medicine, Palo Alto, CA. But, to be more precise, the work began with a research project that Longaker was given back in 1987, while a post doc in the lab of Michael Harrison, University of California, San Francisco.

Harrison, a surgeon then performing groundbreaking prenatal surgery, noticed that babies born after undergoing surgery in the womb healed from their surgeries without any scarring. He asked his postdoc to find out why, and Longaker has been trying to answer that question and understand scar formation ever since.

Longaker and his Stanford colleague Geoffrey Gurtner suspected that the difference between healing inside and outside the womb had something to do with tension. Inside the womb, the skin of the unborn is bathed in fluid and develops in a soft, tension-free state. Outside the womb, human skin is exposed to continuous environmental stresses and must continuously remodel and grow to remain viable, which creates a high level of skin tension.

Following up on Longaker and Gurtner’s suspicion, Mascharak found in a series of mouse experiments that a particular class of fibroblast, a type of cell in skin and other connective tissues, activates a gene called Engrailed-1 during scar formation [3]. To see if mechanical stress played a role in this process, Mascharak and team grew mouse fibroblast cells on either a soft, stress-free gel or on a stiff plastic dish that produced mechanical strain. Importantly, they also tried growing the fibroblasts on the same strain-inducing plastic, but in the presence of a chemical that blocked the mechanical-strain signal.

Their studies showed that fibroblasts grown on the tension-free gel didn’t activate the scar-associated genetic program, unlike fibroblasts growing on the stress-inducing plastic. With the chemical that blocked the cells’ ability to sense the mechanical strain, Engrailed-1 didn’t get switched on either.

They also showed the opposite. When tension was applied to healing surgical incisions in mice, it led to an increase in the number of those fibroblast cells expressing Engrailed-1 and thicker scars.

The researchers went on to make another critical finding. The mechanical stress of a fresh injury turns on a genetic program that leads to scar formation, and that program gets switched on through another protein called Yes-associated protein (YAP). When they blocked this protein with an existing eye drug called verteporfin, skin healed more slowly but without any hint of a scar.

It’s worth noting that scars aren’t just a cosmetic issue. Scars differ from unwounded skin in many ways. They lack hair follicles, glands that produce oil and sweat, and nerves for sensing pain or pressure. Because the fibers that make up scar tissue run parallel to each other instead of being more intricately interwoven, scars also lack the flexibility and strength of healthy skin.

These new findings therefore suggest it may one day be possible to allow wounds to heal without compromising the integrity of the skin. The findings also may have implications for many other medical afflictions that involve scarring, such as liver and lung fibrosis, burns, scleroderma, and scarring of heart tissue after a heart attack. That’s also quite a testament to sticking with a good postdoc project, wherever it may lead. One day, it may even improve public health!

References:

[1] Human skin wounds: A major and snowballing threat to public health and the economy. Sen CK, Gordillo GM, Roy S, Kirsner R, Lambert L, Hunt TK, Gottrup F, Gurtner GC, Longaker MT. Wound Repair Regen. 2009 Nov-Dec;17(6):763-771.

[2] Preventing Engrailed-1 activation in fibroblasts yields wound regeneration without scarring.

Mascharak S, desJardins-Park HE, Davitt MF, Griffin M, Borrelli MR, Moore AL, Chen K, Duoto B, Chinta M, Foster DS, Shen AH, Januszyk M, Kwon SH, Wernig G, Wan DC, Lorenz HP, Gurtner GC, Longaker MT. Science. 2021 Apr 23;372(6540):eaba2374.

[3] Skin fibrosis. Identification and isolation of a dermal lineage with intrinsic fibrogenic potential. Rinkevich Y, Walmsley GG, Hu MS, Maan ZN, Newman AM, Drukker M, Januszyk M, Krampitz GW, Gurtner GC, Lorenz HP, Weissman IL, Longaker MT. Science. 2015 Apr 17;348(6232):aaa2151.

Links:

Skin Health (National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases/NIH)

Scleroderma (NIAMS)

Michael Longaker (Stanford Medicine, Palo Alto, CA)

Geoffrey Gurtner (Stanford Medicine)

NIH Support: National Institute of General Medical Sciences; National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research

Tackling Fibrosis with Synthetic Materials

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

When injury strikes a limb or an organ, our bodies usually heal quickly and correctly. But for some people, the healing process doesn’t shut down properly, leading to excess fibrous tissue, scarring, and potentially life-threatening organ damage.

This permanent scarring, known as fibrosis, can occur in almost every tissue of the body, including the heart and lungs. With support from a 2019 NIH Director’s New Innovator Award, April Kloxin is applying her expertise in materials science and bioengineering to build sophisticated fibrosis-in-a-dish models for unraveling this complex process in her lab at the University of Delaware, Newark.

Though Kloxin is interested in all forms of fibrosis, she’s focusing first on the incurable and often-fatal lung condition called idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF). This condition, characterized by largely unexplained thickening and stiffening of lung tissue, is diagnosed in about 50,000 people each year in the United States.

IPF remains poorly understood, in part because it often is diagnosed when the disease is already well advanced. Kloxin hopes to turn back the clock and start to understand the disease at an earlier stage, when interventions might be more successful. The key is to develop a model that better recapitulates the complexity and irreversibility of the disease process in people.

Building that better model starts with simulating the meshwork of collagen and other proteins in the extracellular matrix (ECM) that undergird every tissue and organ in the body. The ECM’s interactions with our cells are essential in wound healing and, when things go wrong, also in causing fibrosis.

Kloxin will build three-dimensional hydrogels, crosslinked sponge-like networks of polymers, peptides, and proteins, with structures that more accurately capture the biological complexities of human tissues, including the ECMs within fibrous collagen-rich microenvironments. Her synthetic matrices can be triggered with light to lock in place and stiffen. The matrices also will make it possible to culture the lung’s epithelium, or outermost layer of cells, and connective tissue that surrounds it, to study cellular responses as the model shifts from a healthy and flexible to a stiffened, disease-like state.

Kloxin and her team will also integrate into their model system lung cells that have been engineered to fluoresce or light up under a microscope when the wound-healing program activates. Such fluorescent reporters will allow her team to watch for the first time how different cells and their nearby microenvironment respond as the composition of the ECM changes and stiffens. With this system, she’ll also be able to search for small molecules with the ability to turn off excessive wound healing.

The hope is that what’s learned with her New Innovator Award will lead to fresh insights and ultimately new treatments for this mysterious, hard-to-treat condition. But the benefits could be even more wide-ranging. Kloxin thinks that her findings will have implications for the prevention and treatment of other fibrotic diseases as well.

Links:

Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute/NIH)

April Kloxin Group (University of Delaware, Newark)

Kloxin Project Information (NIH RePORTER)

NIH Director’s New Innovator Award (Common Fund)

NIH Support: Common Fund; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute

3D Printing a Human Heart Valve

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

It is now possible to pull up the design of a guitar on a computer screen and print out its parts on a 3D printer equipped with special metal or plastic “inks.” The same technological ingenuity is also now being applied with bioinks—printable gels containing supportive biomaterials and/or cells—to print out tissue, bone, blood vessels, and, even perhaps one day, viable organs.

While there’s a long way to go until then, a team of researchers has reached an important milestone in bioprinting collagen and other extracellular matrix proteins that undergird every tissue and organ in the body. The researchers have become so adept at it that they now can print biomaterials that mimic the structural, mechanical, and biological properties of real human tissues.

Take a look at the video. It shows a life-size human heart valve that’s been printed with their improved collagen bioink. As fluid passes through the aortic valve in a lab test, its three leaf-like flaps open and close like the real thing. All the while, the soft, flexible valve withstands the intense fluid pressure, which mimics that of blood flowing in and out of a beating heart.

The researchers, led by NIH grantee Adam Feinberg, Carnegie Mellon University, Pittsburgh, PA, did it with their latest version of a 3D bioprinting technique featured on the blog a few years ago. It’s called: Freeform Reversible Embedding of Suspended Hydrogels v.2.0. Or, just FRESH v2.0.

The FRESH system uses a bioink that consists of collagen (or other soft biomaterials) embedded in a thick slurry of gelatin microparticles and water. While a number of technical improvements have been made to FRESH v. 2.0, the big one was getting better at bioprinting collagen.

The secret is to dissolve the collagen bioink in an acid solution. When extruded into a neutral support bath, the change in pH drives the rapid assembly of collagen. The ability to extrude miniscule amounts and move the needle anywhere in 3D space enables them to produce amazingly complex, high-resolution structures, layer by layer. The porous microstructure of the printed collagen also helps for incorporating human cells. When printing is complete, the support bath easily melts away by heating to body temperature.

As described in Science, in addition to the working heart valve, the researchers have printed a small model of a heart ventricle. By combining collagen with cardiac muscle cells, they found they could actually control the organization of muscle tissue within the model heart chamber. The 3D-printed ventricles also showed synchronized muscle contractions, just like you’d expect in a living, beating human heart!

That’s not all. Using MRI images of an adult human heart as a template, the researchers created a complete organ structure including internal valves, large veins, and arteries. Based on the vessels they could see in the MRI, they printed even tinier microvessels and showed that the structure could support blood-like fluid flow.

While the researchers have focused the potential of FRESH v.2.0 printing on a human heart, in principle the technology could be used for many other organ systems. But there are still many challenges to overcome. A major one is the need to generate and incorporate billions of human cells, as would be needed to produce a transplantable human heart or other organ.

Feinberg reports more immediate applications of the technology on the horizon, however. His team is working to apply FRESH v.2.0 for producing child-sized replacement tracheas and precisely printed scaffolds for healing wounded muscle tissue.

Meanwhile, the Feinberg lab generously shares its designs with the scientific community via the NIH 3D Print Exchange. This innovative program is helping to bring more 3D scientific models online and advance the field of bioprinting. So we can expect to read about many more exciting milestones like this one from the Feinberg lab.

Reference:

[1] 3D bioprinting of collagen to rebuild components of the human heart. Lee A, Hudson AR, Shiwarski DJ, Tashman JW, Hinton TJ, Yerneni S, Bliley JM, Campbell PG, Feinberg AW. Science. 2019 Aug 2;365(6452):482-487.

Links:

Tissue Engineering and Regenerative Medicine (National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering/NIH)

Regenerative Biomaterials and Therapeutics Group (Carnegie Mellon University, Pittsburgh, PA)

FluidForm (Acton, MA)

3D Bioprinting Open Source Workshops (Carnegie Mellon)

Video: Adam Feinberg on Tissue Engineering to Treat Human Disease (YouTube)

NIH Support: National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development; Common Fund

Building a Smarter Bandage

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Credit: Tufts University, Medford, MA

Smartphones, smartwatches, and smart electrocardiograms. How about a smart bandage?

This image features a prototype of a smart bandage equipped with temperature and pH sensors (lower right) printed directly onto the surface of a thin, flexible medical tape. You also see the “brains” of the operation: a microprocessor (upper left). When the sensors prompt the microprocessor, it heats up a hydrogel heating element in the bandage, releasing drugs and/or other healing substances on demand. It can also wirelessly transmit messages directly to a smartphone to keep patients and doctors updated.

While the smart bandage might help mend everyday cuts and scrapes, it was designed with the intent of helping people with hard-to-heal chronic wounds, such as leg and foot ulcers. Chronic wounds affect millions of Americans, including many seniors [1]. Such wounds are often treated at home and, if managed incorrectly, can lead to infections and potentially serious health problems.

Snapshots of Life: Healing Spinal Cord Injuries

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

When someone suffers a fully severed spinal cord, it’s considered highly unlikely the injury will heal on its own. That’s because the spinal cord’s neural tissue is notorious for its inability to bridge large gaps and reconnect in ways that restore vital functions. But the image above is a hopeful sight that one day that could change.

Here, a mouse neural stem cell (blue and green) sits in a lab dish, atop a special gel containing a mat of synthetic nanofibers (purple). The cell is growing and sending out spindly appendages, called axons (green), in an attempt to re-establish connections with other nearby nerve cells.

Regenerative Medicine: New Clue from Fish about Healing Spinal Cord Injuries

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

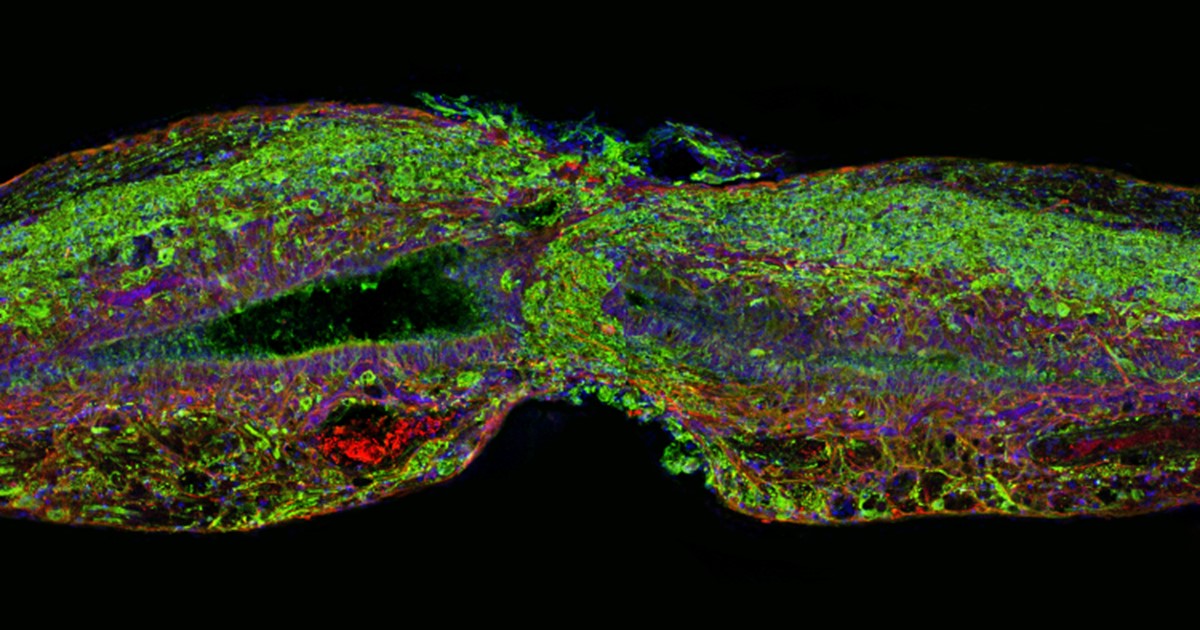

Caption: Tissue section of zebrafish spinal cord regenerating after injury. Glial cells (red) cross the gap between the severed ends first. Neuronal cells (green) soon follow. Cell nuclei are stained blue and purple.

Credit: Mayssa Mokalled and Kenneth Poss, Duke University, Durham, NC

Certain organisms have remarkable abilities to achieve self-healing, and a fascinating example is the zebrafish (Danio rerio), a species of tropical freshwater fish that’s an increasingly popular model organism for biological research. When the fish’s spinal cord is severed, something remarkable happens that doesn’t occur in humans: supportive cells in the nervous system bridge the gap, allowing new nerve tissue to restore the spinal cord to full function within weeks.

Pretty incredible, but how does this occur? NIH-funded researchers have just found an important clue. They’ve discovered that the zebrafish’s damaged cells secrete a molecule known as connective tissue growth factor a (CTGFa) that is essential in regenerating its severed spinal cord. What’s particularly encouraging to those looking for ways to help the 12,000 Americans who suffer spinal cord injuries each year is that humans also produce a form of CTGF. In fact, the researchers found that applying human CTGF near the injured site even accelerated the regenerative process in zebrafish. While this growth factor by itself is unlikely to produce significant spinal cord regeneration in human patients, the findings do offer a promising lead for researchers pursuing the next generation of regenerative therapies.

Creative Minds: Can Salamanders Show Us How to Regrow Limbs?

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Jessica Whited /Credit: LightChaser Photography

Jessica Whited enjoys spending time with her 6-year-old twin boys, reading them stories, and letting their imaginations roam. One thing Whited doesn’t need to feed their curiosity about, however, is salamanders—they hear about those from Mom almost every day. Whited already has about 1,000 rare axolotl salamanders in her lab at Harvard University and Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Cambridge, MA. But caring for the 9-inch amphibians, which originate from the lakes and canals underlying Mexico City, certainly isn’t child’s play. Axolotls are entirely aquatic–their name translates to “water monster”; they like to bite each other; and they take 9 months to reach adulthood.

Like many other species of salamander, the axolotl (Ambystoma mexicanum) possesses a remarkable, almost magical, ability to grow back lost or damaged limbs. Whited’s interest in this power of limb regeneration earned her a 2015 NIH Director’s New Innovator Award. Her goal is to discover how the limbs of these salamanders know exactly where they’ve been injured and start regrowing from precisely that point, while at the same time forging vital new nerve connections to the brain. Ultimately, she hopes her work will help develop strategies to explore the possibility of “awakening” this regenerative ability in humans with injured or severed limbs.

Snapshots of Life: Fish Awash in Color

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

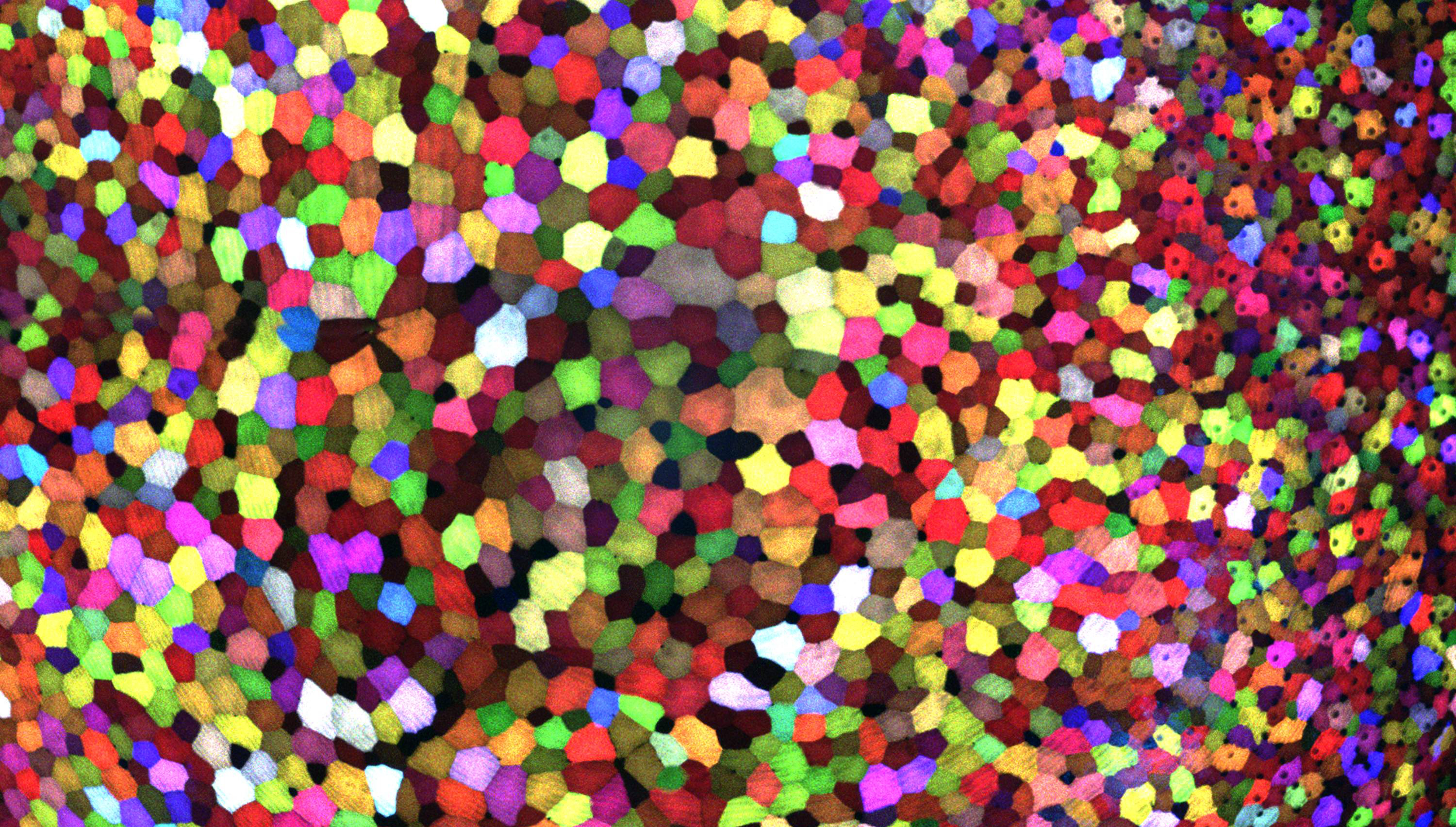

If this image makes you think of a modern art, you’re not alone. But what you’re actually seeing are hundreds of live cells from a tiny bit (0.0003348 square inches) of skin on the tail fin of a genetically engineered adult zebrafish. Zebrafish are normally found in tropical freshwater and are a favorite research model to study vertebrate development and tissue regeneration. The cells have been labeled with a cool, new fluorescent imaging tool called Skinbow. It uniquely color codes cells by getting them to express genes encoding red, green, and blue fluorescent proteins at levels that are randomly determined. The different ratios of these colorful proteins mix to give each cell a distinctive hue when imaged under a microscope. Here, you can see more than 70 detectable Skinbow colors that make individual cells as visually distinct from one another as jellybeans in a jar.

Skinbow is the creation of NIH-supported scientists Chen-Hui Chen and Kenneth Poss at Duke University, Durham, NC, with imaging computational help from collaborators Stefano Di Talia and Alberto Puliafito. As reported recently in the journal Developmental Cell [1], Skinbow’s distinctive spectrum of color occurs primarily in the outermost part of the skin in a layer of non-dividing epithelial cells. Using Skinbow, Poss and colleagues tracked these epithelial cells, individually and as a group, over their entire 2 to 3 week lifespans in the zebrafish. This gave them an unprecedented opportunity to track the cellular dynamics of wound healing or the regeneration of lost tissue over time. While Skinbow only works in zebrafish for now, in theory, it could be adapted to mice and maybe even humans to study skin and possibly other organs.

Next Page