collagen

Tackling Fibrosis with Synthetic Materials

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

When injury strikes a limb or an organ, our bodies usually heal quickly and correctly. But for some people, the healing process doesn’t shut down properly, leading to excess fibrous tissue, scarring, and potentially life-threatening organ damage.

This permanent scarring, known as fibrosis, can occur in almost every tissue of the body, including the heart and lungs. With support from a 2019 NIH Director’s New Innovator Award, April Kloxin is applying her expertise in materials science and bioengineering to build sophisticated fibrosis-in-a-dish models for unraveling this complex process in her lab at the University of Delaware, Newark.

Though Kloxin is interested in all forms of fibrosis, she’s focusing first on the incurable and often-fatal lung condition called idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF). This condition, characterized by largely unexplained thickening and stiffening of lung tissue, is diagnosed in about 50,000 people each year in the United States.

IPF remains poorly understood, in part because it often is diagnosed when the disease is already well advanced. Kloxin hopes to turn back the clock and start to understand the disease at an earlier stage, when interventions might be more successful. The key is to develop a model that better recapitulates the complexity and irreversibility of the disease process in people.

Building that better model starts with simulating the meshwork of collagen and other proteins in the extracellular matrix (ECM) that undergird every tissue and organ in the body. The ECM’s interactions with our cells are essential in wound healing and, when things go wrong, also in causing fibrosis.

Kloxin will build three-dimensional hydrogels, crosslinked sponge-like networks of polymers, peptides, and proteins, with structures that more accurately capture the biological complexities of human tissues, including the ECMs within fibrous collagen-rich microenvironments. Her synthetic matrices can be triggered with light to lock in place and stiffen. The matrices also will make it possible to culture the lung’s epithelium, or outermost layer of cells, and connective tissue that surrounds it, to study cellular responses as the model shifts from a healthy and flexible to a stiffened, disease-like state.

Kloxin and her team will also integrate into their model system lung cells that have been engineered to fluoresce or light up under a microscope when the wound-healing program activates. Such fluorescent reporters will allow her team to watch for the first time how different cells and their nearby microenvironment respond as the composition of the ECM changes and stiffens. With this system, she’ll also be able to search for small molecules with the ability to turn off excessive wound healing.

The hope is that what’s learned with her New Innovator Award will lead to fresh insights and ultimately new treatments for this mysterious, hard-to-treat condition. But the benefits could be even more wide-ranging. Kloxin thinks that her findings will have implications for the prevention and treatment of other fibrotic diseases as well.

Links:

Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute/NIH)

April Kloxin Group (University of Delaware, Newark)

Kloxin Project Information (NIH RePORTER)

NIH Director’s New Innovator Award (Common Fund)

NIH Support: Common Fund; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute

3D Printing a Human Heart Valve

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

It is now possible to pull up the design of a guitar on a computer screen and print out its parts on a 3D printer equipped with special metal or plastic “inks.” The same technological ingenuity is also now being applied with bioinks—printable gels containing supportive biomaterials and/or cells—to print out tissue, bone, blood vessels, and, even perhaps one day, viable organs.

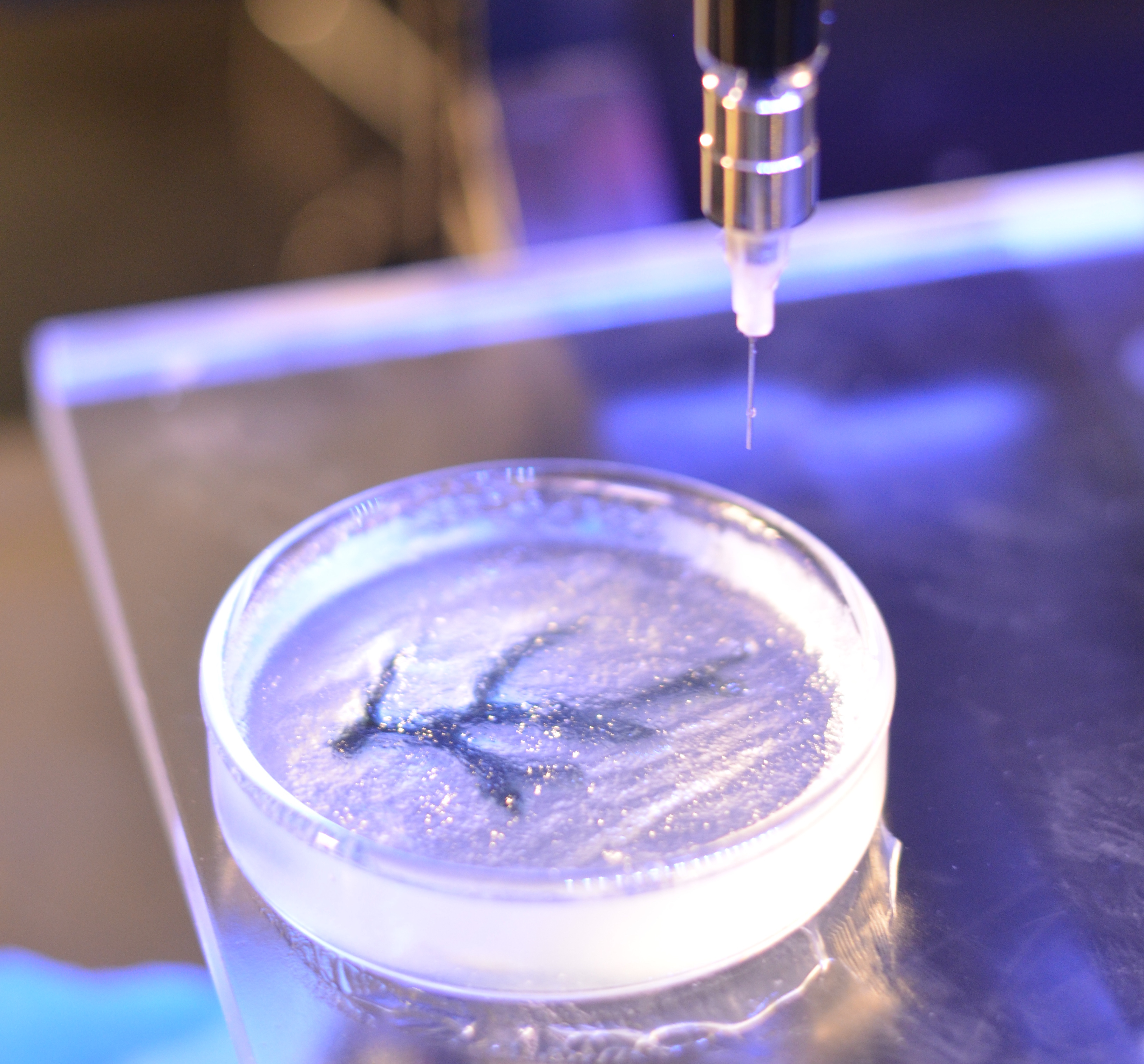

While there’s a long way to go until then, a team of researchers has reached an important milestone in bioprinting collagen and other extracellular matrix proteins that undergird every tissue and organ in the body. The researchers have become so adept at it that they now can print biomaterials that mimic the structural, mechanical, and biological properties of real human tissues.

Take a look at the video. It shows a life-size human heart valve that’s been printed with their improved collagen bioink. As fluid passes through the aortic valve in a lab test, its three leaf-like flaps open and close like the real thing. All the while, the soft, flexible valve withstands the intense fluid pressure, which mimics that of blood flowing in and out of a beating heart.

The researchers, led by NIH grantee Adam Feinberg, Carnegie Mellon University, Pittsburgh, PA, did it with their latest version of a 3D bioprinting technique featured on the blog a few years ago. It’s called: Freeform Reversible Embedding of Suspended Hydrogels v.2.0. Or, just FRESH v2.0.

The FRESH system uses a bioink that consists of collagen (or other soft biomaterials) embedded in a thick slurry of gelatin microparticles and water. While a number of technical improvements have been made to FRESH v. 2.0, the big one was getting better at bioprinting collagen.

The secret is to dissolve the collagen bioink in an acid solution. When extruded into a neutral support bath, the change in pH drives the rapid assembly of collagen. The ability to extrude miniscule amounts and move the needle anywhere in 3D space enables them to produce amazingly complex, high-resolution structures, layer by layer. The porous microstructure of the printed collagen also helps for incorporating human cells. When printing is complete, the support bath easily melts away by heating to body temperature.

As described in Science, in addition to the working heart valve, the researchers have printed a small model of a heart ventricle. By combining collagen with cardiac muscle cells, they found they could actually control the organization of muscle tissue within the model heart chamber. The 3D-printed ventricles also showed synchronized muscle contractions, just like you’d expect in a living, beating human heart!

That’s not all. Using MRI images of an adult human heart as a template, the researchers created a complete organ structure including internal valves, large veins, and arteries. Based on the vessels they could see in the MRI, they printed even tinier microvessels and showed that the structure could support blood-like fluid flow.

While the researchers have focused the potential of FRESH v.2.0 printing on a human heart, in principle the technology could be used for many other organ systems. But there are still many challenges to overcome. A major one is the need to generate and incorporate billions of human cells, as would be needed to produce a transplantable human heart or other organ.

Feinberg reports more immediate applications of the technology on the horizon, however. His team is working to apply FRESH v.2.0 for producing child-sized replacement tracheas and precisely printed scaffolds for healing wounded muscle tissue.

Meanwhile, the Feinberg lab generously shares its designs with the scientific community via the NIH 3D Print Exchange. This innovative program is helping to bring more 3D scientific models online and advance the field of bioprinting. So we can expect to read about many more exciting milestones like this one from the Feinberg lab.

Reference:

[1] 3D bioprinting of collagen to rebuild components of the human heart. Lee A, Hudson AR, Shiwarski DJ, Tashman JW, Hinton TJ, Yerneni S, Bliley JM, Campbell PG, Feinberg AW. Science. 2019 Aug 2;365(6452):482-487.

Links:

Tissue Engineering and Regenerative Medicine (National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering/NIH)

Regenerative Biomaterials and Therapeutics Group (Carnegie Mellon University, Pittsburgh, PA)

FluidForm (Acton, MA)

3D Bioprinting Open Source Workshops (Carnegie Mellon)

Video: Adam Feinberg on Tissue Engineering to Treat Human Disease (YouTube)

NIH Support: National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development; Common Fund

Snapshots of Life: An Elegant Design

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Credit: David Sleboda and Thomas Roberts, Brown University, Providence, RI

Over the past few years, my blog has highlighted winners from the annual BioArt contest sponsored by the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology (FASEB). So, let’s keep a good thing going with one of the amazing scientific images that captured top honors in FASEB’s latest competition: a scanning electron micrograph of the hamstring muscle of a bullfrog.

That’s right, a bullfrog, For decades, researchers have used the American bullfrog, Rana catesbeiana, as a model for studying the physiology and biomechanics of skeletal muscles. My own early work with electron microscopy, as a student at Yale in the 1970s, was devoted to producing images from this very tissue. Thanks to its disproportionately large skeletal muscles, this common amphibian has played a critical role in helping to build the knowledge base for understanding how these muscles work in other organisms, including humans.

Revealed in this picture is the intricate matrix of connective tissue that holds together the frog’s hamstring muscle, with the muscle fibers themselves having been digested away with chemicals. And running diagonally, from lower left to upper right, you can see a band of fibrils made up of a key structural protein called collagen.