spinal cord injuries

The Amazing Brain: Motor Neurons of the Cervical Spine

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Today, you may have opened a jar, done an upper body workout, played a guitar or a piano, texted a friend, or maybe even jotted down a grocery list longhand. All of these “skilled” arm, wrist, and hand movements are made possible by the bundled nerves, or circuits, running through a part of the central nervous system in the neck area called the cervical spine.

This video, which combines sophisticated imaging and computation with animation, shows the density of three types of nerve cells in the mouse cervical spine. There are the V1 interneurons (red), which sit between sensory and motor neurons; motor neurons associated with controlling the movement of the bicep (blue); and motor neurons associated with controlling the tricep (green).

At 4 seconds, the 3D animation morphs to show all the colors and cells intermixed as they are naturally in the cervical spine. At 8 seconds, the animation highlights the density of these three cells types. Notice in the bottom left corner, a light icon appears indicating the different imaging perspectives. What’s unique here is the frontal, or rostral, view of the cervical spine. The cervical spine is typically imaged from a lateral, or side, perspective.

Starting at 16 seconds, the animation highlights the location and density of each of the individual neurons. For the grand finale, viewers zoom off on a brief fly-through of the cervical spine and a flurry of reds, blues, and greens.

The video comes from Jamie Anne Mortel, a research assistant in the lab of Samuel Pfaff, Salk Institute, La Jolla, CA. Mortel is part of a team supported by the NIH-led Brain Research through Advancing Innovative Neurotechnologies® (BRAIN) Initiative that’s developing a comprehensive atlas of the circuitry within the cervical spine that controls how mice control their forelimb movements, such as reaching and grasping.

This basic research will provide a better understanding of how the mammalian brain and spinal cord work together to produce movement. More than that, this research may provide valuable clues into better treating paralysis to arms, wrists, and/or hands caused by neurological diseases and spinal cord injuries.

As a part of this project, the Pfaff lab has been busy developing a software tool to take their imaging data from different parts of the cervical spine and present it in 3D. Mortel, who likes to make cute cartoon animations in her spare time, noticed that the software lacked animation capability. So she took the initiative and spent the next three weeks working after hours to produce this video—her first attempt at scientific animation. No doubt she must have been using a lot of wrist and hand movements!

With a positive response from her Salk labmates, Mortel decided to enter her scientific animation debut in the 2021 Show Us BRAINs! Photo and Video Contest. To her great surprise and delight, Mortel won third place in the video competition. Congratulations, and continued success for you and the team in producing this much-needed atlas to define the circuitry underlying skilled arm, wrist, and hand movements.

Links:

Brain Research through Advancing Innovative Neurotechnologies® (BRAIN) Initiative (NIH)

Spinal Cord Injury Information Page (National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke/NIH)

Samuel Pfaff (Salk Institute, La Jolla, CA)

Show Us Your BRAINs! Photo and Video Contest (Brain Initiative/NIH)

NIH Support: National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke

Understanding Neuronal Diversity in the Spinal Cord

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

The spinal cord, as a key part of our body’s central nervous system, contains millions of neurons that actively convey sensory and motor (movement) information to and from the brain. Scientists have long sorted these spinal neurons into what they call “cardinal” classes, a classification system based primarily on the developmental origin of each nerve cell. Now, by taking advantage of the power of single-cell genetic analysis, they’re finding that spinal neurons are more diverse than once thought.

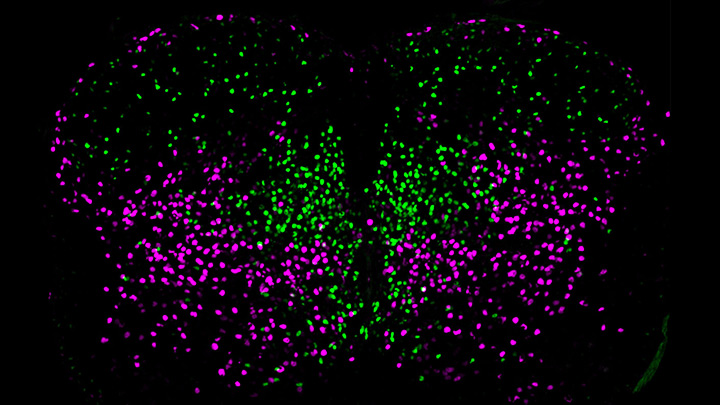

This image helps to visualize the story. Each dot represents the nucleus of a spinal neuron in a mouse; humans have a very similar arrangement. Most of these neurons are involved in the regulation of motor control, but they also differ in important ways. Some are involved in local connections (green), such as those that signal outward to a limb and prompt us to pull away reflexively when we touch painful stimuli, such as a hot frying pan. Others are involved in long-range connections (magenta), relaying commands across spinal segments and even upward to the brain. These enable us, for example, to swing our arms while running to help maintain balance.

It turns out that these two types of spinal neurons also have distinctive genetic signatures. That’s why researchers could label them here in different colors and tell them apart. Being able to distinguish more precisely among spinal neurons will prove useful in identifying precisely which ones are affected by a spinal cord injury or neurodegenerative disease, key information in learning to engineer new tissue to heal the damage.

This image comes from a study, published recently in the journal Science, conducted by an NIH-supported team led by Samuel Pfaff, Salk Institute for Biological Studies, La Jolla, CA. Pfaff and his colleagues, including Peter Osseward and Marito Hayashi, realized that the various classes and subtypes of neurons in our spines arose over the course of evolutionary time. They reasoned that the most-primitive original neurons would have gradually evolved subtypes with more specialized and diverse capabilities. They thought they could infer this evolutionary history by looking for conserved and then distinct, specialized gene-expression signatures in the different neural subtypes.

The researchers turned to single-cell RNA sequencing technologies to look for important similarities and differences in the genes expressed in nearly 7,000 mouse spinal neurons. They then used this vast collection of genomic data to group the neurons into closely related clusters, in much the same way that scientists might group related organisms into an evolutionary family tree based on careful study of their DNA.

The first major gene expression pattern they saw divided the spinal neurons into two types: sensory-related and motor-related. This suggested to them that one of the first steps in spinal cord evolution may have been a division of labor of spinal neurons into those two fundamentally important roles.

Further analyses divided the sensory-related neurons into excitatory neurons, which make neurons more likely to fire; and inhibitory neurons, which dampen neural firing. Then, the researchers zoomed in on motor-related neurons and found something unexpected. They discovered the cells fell into two distinct molecular groups based on whether they had long-range or short-range connections in the body. Researches were even more surprised when further study showed that those distinct connectivity signatures were shared across cardinal classes.

All of this means that, while previously scientists had to use many different genetic tags to narrow in on a particular type of neuron, they can now do it with just two: a previously known tag for cardinal class and the newly discovered genetic tag for long-range vs. short-range connections.

Not only is this newfound ability a great boon to basic neuroscientists, it also could prove useful for translational and clinical researchers trying to determine which specific neurons are affected by a spinal injury or disease. Eventually, it may even point the way to strategies for regrowing just the right set of neurons to repair serious neurologic problems. It’s a vivid reminder that fundamental discoveries, such as this one, often can lead to unexpected and important breakthroughs with potential to make a real difference in people’s lives.

Reference:

[1] Conserved genetic signatures parcellate cardinal spinal neuron classes into local and projection subsets. Osseward PJ 2nd, Amin ND, Moore JD, Temple BA, Barriga BK, Bachmann LC, Beltran F Jr, Gullo M, Clark RC, Driscoll SP, Pfaff SL, Hayashi M. Science. 2021 Apr 23;372(6540):385-393.

Links:

What Are the Parts of the Nervous System? (Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development/NIH)

Spinal Cord Injury (National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke/NIH)

Samuel Pfaff (Salk Institute, La Jolla, CA)

NIH Support: National Institute of Mental Health; National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke; Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development

Snapshots of Life: Healing Spinal Cord Injuries

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

When someone suffers a fully severed spinal cord, it’s considered highly unlikely the injury will heal on its own. That’s because the spinal cord’s neural tissue is notorious for its inability to bridge large gaps and reconnect in ways that restore vital functions. But the image above is a hopeful sight that one day that could change.

Here, a mouse neural stem cell (blue and green) sits in a lab dish, atop a special gel containing a mat of synthetic nanofibers (purple). The cell is growing and sending out spindly appendages, called axons (green), in an attempt to re-establish connections with other nearby nerve cells.

Regenerative Medicine: New Clue from Fish about Healing Spinal Cord Injuries

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

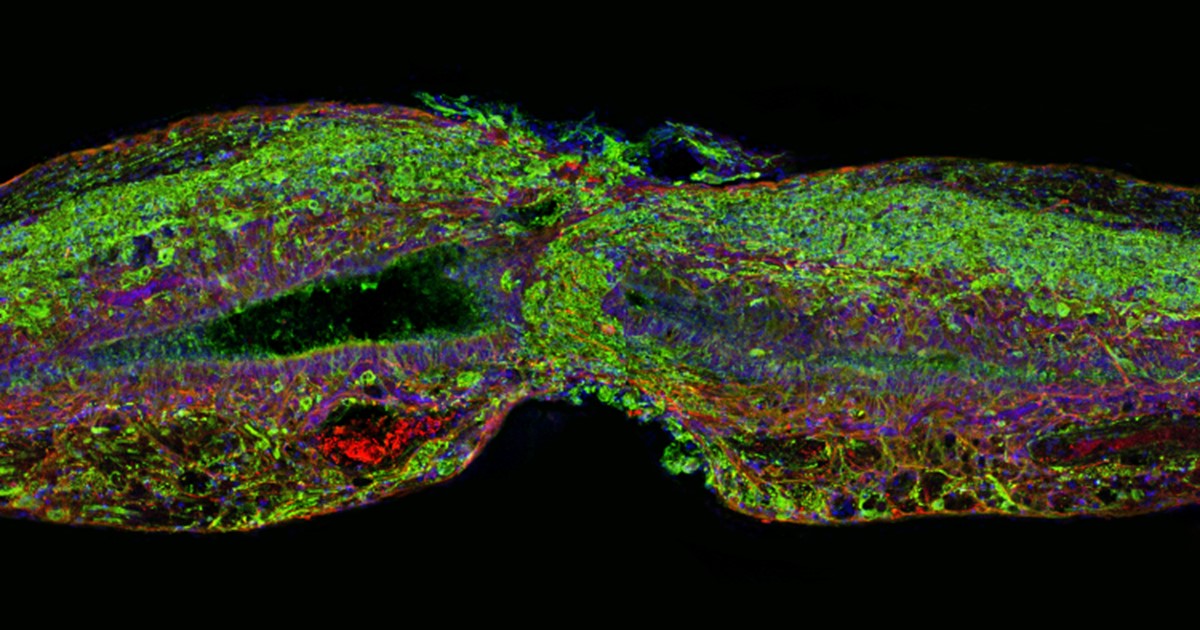

Caption: Tissue section of zebrafish spinal cord regenerating after injury. Glial cells (red) cross the gap between the severed ends first. Neuronal cells (green) soon follow. Cell nuclei are stained blue and purple.

Credit: Mayssa Mokalled and Kenneth Poss, Duke University, Durham, NC

Certain organisms have remarkable abilities to achieve self-healing, and a fascinating example is the zebrafish (Danio rerio), a species of tropical freshwater fish that’s an increasingly popular model organism for biological research. When the fish’s spinal cord is severed, something remarkable happens that doesn’t occur in humans: supportive cells in the nervous system bridge the gap, allowing new nerve tissue to restore the spinal cord to full function within weeks.

Pretty incredible, but how does this occur? NIH-funded researchers have just found an important clue. They’ve discovered that the zebrafish’s damaged cells secrete a molecule known as connective tissue growth factor a (CTGFa) that is essential in regenerating its severed spinal cord. What’s particularly encouraging to those looking for ways to help the 12,000 Americans who suffer spinal cord injuries each year is that humans also produce a form of CTGF. In fact, the researchers found that applying human CTGF near the injured site even accelerated the regenerative process in zebrafish. While this growth factor by itself is unlikely to produce significant spinal cord regeneration in human patients, the findings do offer a promising lead for researchers pursuing the next generation of regenerative therapies.