Danio rerio

First Day in the Life of Nine Amazing Creatures

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Credit: Tessa Montague, Harvard University, and Zuzka Vavrušová, University of California, San Francisco

Each summer for the last 125 years, students from around the country have traveled to the Marine Biological Laboratory (MBL), Woods Hole, MA, for an intensive course in embryology. While visiting this peaceful and scenic village on Cape Cod, they’re exposed to a dizzying array of organisms and state-of-the-art techniques to study their development.

Finding Brain Circuits Tied to Alertness

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Everybody knows that it’s important to stay alert behind the wheel or while out walking on the bike path. But our ability to react appropriately to sudden dangers is influenced by whether we feel momentarily tired, distracted, or anxious. How is it that the brain can transition through such different states of consciousness while performing the same routine task, even as its basic structure and internal wiring remain unchanged?

A team of NIH-funded researchers may have found an important clue in zebrafish, a popular organism for studying how the brain works. Using a powerful new method that allowed them to find and track brain circuits tied to alertness, the researchers discovered that this mental state doesn’t work like an on/off switch. Rather, alertness involves several distinct brain circuits working together to bring the brain to attention. As shown in the video above that was taken at cellular resolution, different types of neurons (green) secrete different kinds of chemical messengers across the zebrafish brain to affect the transition to alertness. The messengers shown are: serotonin (red), acetylcholine (blue-green), and dopamine and norepinephrine (yellow).

What’s also fascinating is the researchers found that many of the same neuronal cell types and brain circuits are essential to alertness in zebrafish and mice, despite the two organisms being only distantly related. That suggests these circuits are conserved through evolution as an early fight-or-flight survival behavior essential to life, and they are therefore likely to be important for controlling alertness in people too. If correct, it would tell us where to look in the brain to learn about alertness not only while doing routine stuff but possibly for understanding dysfunctional brain states, ranging from depression to post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

Snapshots of Life: Coming Face to Face with Development

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Credit: Oscar Ruiz and George Eisenhoffer, University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston

Zebrafish (Danio rerio) is a favorite model for studying development, in part because its transparent embryos make it possible to produce an ever-growing array of amazingly informative images. For one recent example, check out this Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology’s 2016 BioArt winner, which shows the developing face of a 6-day-old zebrafish larva.

Yes, those downturned “lips” are indeed cells that will go on to become the fish’s mouth. But all is not quite what it appears: the two dark circles that look like eyes are actually developing nostrils. Both the nostrils and mouth express high levels of F-actin (green), a structural protein that helps orchestrate cell movement. Meanwhile, the two bulging areas on either side of the fish’s head, which are destined to become eyes and skin, express keratin (red).

Oscar Ruiz, who works in the lab of George Eisenhoffer at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, used a confocal microscope to create this image. What was most innovative about his work was not the microscope itself, but how he prepared the sample for imaging. With traditional methods, researchers can only image the faces of zebrafish larvae from the side or the bottom. However, the Eisenhoffer lab has devised a new method of preparing fish larvae that makes it possible to image their faces head-on. This has enabled the team to visualize facial development at much higher resolution than was previously possible.

Regenerative Medicine: New Clue from Fish about Healing Spinal Cord Injuries

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

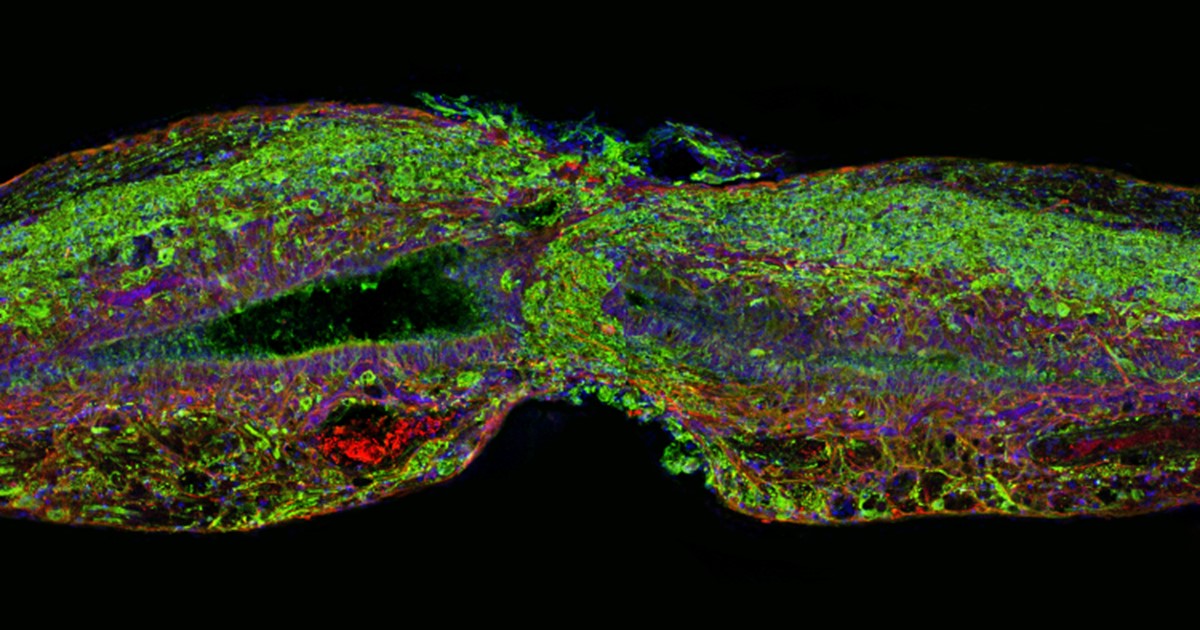

Caption: Tissue section of zebrafish spinal cord regenerating after injury. Glial cells (red) cross the gap between the severed ends first. Neuronal cells (green) soon follow. Cell nuclei are stained blue and purple.

Credit: Mayssa Mokalled and Kenneth Poss, Duke University, Durham, NC

Certain organisms have remarkable abilities to achieve self-healing, and a fascinating example is the zebrafish (Danio rerio), a species of tropical freshwater fish that’s an increasingly popular model organism for biological research. When the fish’s spinal cord is severed, something remarkable happens that doesn’t occur in humans: supportive cells in the nervous system bridge the gap, allowing new nerve tissue to restore the spinal cord to full function within weeks.

Pretty incredible, but how does this occur? NIH-funded researchers have just found an important clue. They’ve discovered that the zebrafish’s damaged cells secrete a molecule known as connective tissue growth factor a (CTGFa) that is essential in regenerating its severed spinal cord. What’s particularly encouraging to those looking for ways to help the 12,000 Americans who suffer spinal cord injuries each year is that humans also produce a form of CTGF. In fact, the researchers found that applying human CTGF near the injured site even accelerated the regenerative process in zebrafish. While this growth factor by itself is unlikely to produce significant spinal cord regeneration in human patients, the findings do offer a promising lead for researchers pursuing the next generation of regenerative therapies.