monocyte

Working to Improve Immunotherapy for Lung Cancer

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

For those who track cancer statistics, this year started off on a positive note with word that lung cancer deaths continue to decline in the United States [1]. While there’s plenty of credit to go around for that encouraging news—and continued reduction in smoking is a big factor—some of this progress likely can be ascribed to a type of immunotherapy, called PD-1 inhibitors. This revolutionary approach has dramatically changed the treatment landscape for the most common type of lung cancer, non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC).

PD-1 inhibitors, which have only been available for about five years, prime one component of a patient’s own immune system, called T cells, to seek and destroy malignant cells in the lungs. Unfortunately, however, only about 20 percent of people with NSCLC respond to PD-1 inhibitors. So, many researchers, including the team of A. McGarry Houghton, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, are working hard to extend the benefits of immunotherapy to more cancer patients.

The team’s latest paper, published in JCI Insight [2], reveals that one culprit behind a poor response to immunotherapy may be the immune system’s own first responders: neutrophils. Billions of neutrophils circulate throughout the body to track down abnormalities, such as harmful bacteria and malignant cells. They also contact other parts of the immune system, including T cells, if help is needed to eliminate the health threat.

In their study, the Houghton team, led by Julia Kargl, combined several lab techniques to take a rigorous, unbiased look at the immune cell profiles of tumor samples from dozens of NSCLC patients who received PD-1 inhibitors as a frontline treatment. The micrographs above show tumor samples from two of these patients.

In the image on the left, large swaths of T cells (light blue) have infiltrated the cancer cells (white specks). Interestingly, other immune cells, including neutrophils (magenta), are sparse.

In contrast, in the image on the right, T cells (light blue) are sparse. Instead, the tumor teems with other types of immune cells, including macrophages (red), two types of monocytes (yellow, green), and, most significantly, lots of neutrophils (magenta). These cells arise from myeloid progenitor cells in the bone marrow, while T cells arise from the marrow’s lymphoid progenitor cell.

Though the immune profiles of some tumor samples were tough to classify, the researchers found that most fit neatly into two subgroups: tumors showing active levels of T cell infiltration (like the image on the left) or those with large numbers of myeloid immune cells, especially neutrophils (like the image on the right). This dichotomy then served as a reliable predictor of treatment outcome. In the tumor samples with majority T cells, the PD-1 inhibitor worked to varying degrees. But in the tumor samples with predominantly neutrophil infiltration, the treatment failed.

Houghton’s team has previously found that many cancers, including NSCLC, actively recruit neutrophils, turning them into zombie-like helpers that falsely signal other immune cells, like T cells, to stay away. Based on this information, Houghton and colleagues used a mouse model of lung cancer to explore a possible way to increase the success rate of PD-1 immunotherapy.

In their mouse experiments, the researchers found that when PD-1 was combined with an existing drug that inhibits neutrophils, lung tumors infiltrated with neutrophils were converted into tumors infiltrated by T cells. The tumors treated with the combination treatment also expressed genes associated with an active immunotherapy response.

This year, January brought encouraging news about decreasing deaths from lung cancer. But with ongoing basic research, like this study, to tease out the mechanisms underlying the success and failure of immunotherapy, future months may bring even better news.

References:

[1] Cancer statistics, 2020. Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. CA Cancer J Clin. 2020 Jan;70(1):7-30.

[2] Neutrophil content predicts lymphocyte depletion and anti-PD1 treatment failure in NSCLC. Kargl J, Zhu X, Zhang H, Yang GHY, Friesen TJ, Shipley M, Maeda DY, Zebala JA, McKay-Fleisch J, Meredith G, Mashadi-Hossein A, Baik C, Pierce RH, Redman MW, Thompson JC, Albelda SM, Bolouri H, Houghton AM. JCI Insight. 2019 Dec 19;4(24).

[3] Neutrophils dominate the immune cell composition in non-small cell lung cancer. Kargl J, Busch SE, Yang GH, Kim KH, Hanke ML, Metz HE, Hubbard JJ, Lee SM, Madtes DK, McIntosh MW, Houghton AM. Nat Commun. 2017 Feb 1;8:14381.

Links:

Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Treatment (PDQ®)–Patient Version (National Cancer Institute/NIH)

Spotlight on McGarry Houghton (Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle)

Houghton Lab (Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center)

NIH Support: National Cancer Institute

Replenishing the Liver’s Immune Protections

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

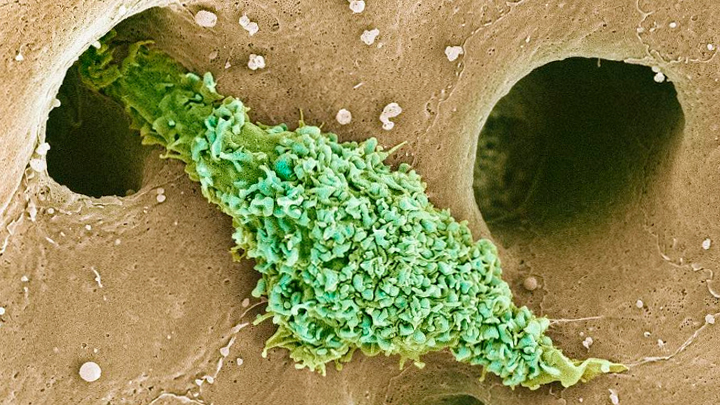

Most of our immune cells circulate throughout the bloodstream to serve as a roving security force against infection. But some immune cells don’t travel much at all and instead safeguard a specific organ or tissue. That’s what you are seeing in this electron micrograph of a type of scavenging macrophage, called a Kupffer cell (green), which resides exclusively in the liver (brown).

Normally, Kupffer cells appear in the liver during the early stages of mammalian development and stay put throughout life to protect liver cells, clean up old red blood cells, and regulate iron levels. But in their experimental system, Christopher Glass and his colleagues from University of California, San Diego, removed all original Kupffer cells from a young mouse to see if this would allow signals from the liver that encourage the development of new Kupffer cells.

The NIH-funded researchers succeeded in setting up the right conditions to spur a heavy influx of circulating precursor immune cells, called monocytes, into the liver, and then prompted those monocytes to turn into the replacement Kupffer cells. In a recent study in the journal Immunity, the team details the specific genomic changes required for the monocytes to differentiate into Kupffer cells [1]. This information will help advance the study of Kupffer cells and their role in many liver diseases, including nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), which affects an estimated 3 to 12 percent of U.S. adults [2].

The new work also has broad implications for immunology research because it provides additional evidence that circulating monocytes contain genomic instructions that, when activated in the right way by nearby cells or other factors, can prompt the monocytes to develop into various, specialized types of scavenging macrophages. For example, in the mouse system, Glass’s team found that the endothelial cells lining the liver’s blood vessels, which is where Kupffer cells hang out, emit biochemical distress signals when their immune neighbors disappear.

While more details need to be worked out, this study is another excellent example of how basic research, including the ability to query single cells about their gene expression programs, is generating fundamental knowledge about the nature and behavior of living systems. Such knowledge is opening new possibilities to more precise ways of treating and preventing diseases all throughout the body, including those involving Kupffer cells and the liver.

References:

[1] Liver-Derived Signals Sequentially Reprogram Myeloid Enhancers to Initiate and Maintain Kupffer Cell Identity. Sakai M, Troutman TD, Seidman JS, Ouyang Z, Spann NJ, Abe Y, Ego KM, Bruni CM, Deng Z, Schlachetzki JCM, Nott A, Bennett H, Chang J, Vu BT, Pasillas MP, Link VM, Texari L, Heinz S, Thompson BM, McDonald JG, Geissmann F3, Glass CK. Immunity. 2019 Oct 15;51(4):655-670.

[2] Recommendations for diagnosis, referral for liver biopsy, and treatment of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Spengler EK, Loomba R. Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 2015;90(9):1233–1246.

Links:

Liver Disease (National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases/NIH)

Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease & NASH (NIDDK)

Glass Laboratory (University of California, San Diego)

NIH Support: National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; National Institute of General Medical Sciences; National Cancer Institute