synapse

Celebrating the Power of Connection This Holiday Season

Posted on by Lawrence Tabak, D.D.S., Ph.D.

Happy holidays to one and all! This short science video brings to mind all those twinkling lights now brightening the night, as we mark the beginning of winter and shortest day of the year. This video also helps to remind us about the power of connection this holiday season.

It shows a motor neuron in a mouse’s primary motor cortex. In this portion of the brain, which controls voluntary movement, heavily branched neural projections interconnect, sending and receiving signals to and from distant parts of the body. A single motor neuron can receive thousands of inputs at a time from other branching sensory cells, depicted in the video as an array of blinking lights. It’s only through these connections—through open communication and cooperation—that voluntary movements are possible to navigate and enjoy our world in all its wonder. One neuron, like one person, can’t do it all alone.

This power of connection, captured in this award-winning video from the 2022 Show Us Your Brains Photo and Video contest, comes from Forrest Collman, Allen Institute for Brain Science, Seattle. The contest is part of NIH’s Brain Research Through Advancing Innovative Neurotechnologies® (BRAIN) Initiative.

In the version above, we’ve taken some liberties with the original video to enhance the twinkling lights from the synaptic connections. But creating the original was quite a task. Collman sifted through reams of data from high-resolution electron microscopy imaging of the motor cortex to masterfully reconstruct this individual motor neuron and its connections.

Those data came from The Machine Intelligence from Cortical Networks (MICrONS) program, supported by the Intelligence Advanced Research Projects Activity (IARPA). It’s part of the Office of the Director of National Intelligence, one of NIH’s governmental collaborators in the BRAIN Initiative.

The MICrONS program aims to better understand the brain’s internal wiring. With this increased knowledge, researchers will develop more sophisticated machine learning algorithms for artificial intelligence applications, which will in turn advance fundamental basic science discoveries and the practice of life-saving medicine. For instance, these applications may help in the future to detect and evaluate a broad range of neural conditions, including those that affect the primary motor cortex.

Pretty cool stuff. So, as you spend this holiday season with friends and family, let this video and its twinkling lights remind you that there’s much more to the season than eating, drinking, and watching football games.

The holidays are very much about the power of connection for people of all faiths, beliefs, and traditions. It’s about taking time out from the everyday to join together to share memories of days gone by as we build new memories and stronger bonds of cooperation for the years to come. With this in mind, happy holidays to one and all.

Links:

“NIH BRAIN Initiative Unveils Detailed Atlas of the Mammalian Primary Motor Cortex,” NIH News Release, October 6, 2021

Forrest Collman (Allen Institute for Brain Science, Seattle)

Brain Research Through Advancing Innovative Neurotechnologies® (BRAIN) Initiative (NIH)

Show Us Your Brains Photo and Video Contest (BRAIN Initiative)

Multiplex Rainbow Technology Offers New View of the Brain

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

The NIH-led Brain Research through Advancing Innovative Neurotechnologies® (BRAIN) Initiative is revolutionizing our understanding of how the brain works through its creation of new imaging tools. One of the latest advances—used to produce this rainbow of images—makes it possible to view dozens of proteins in rapid succession in a single tissue sample containing thousands of neural connections, or synapses.

Apart from their colors, most of these images look nearly identical at first glance. But, upon closer inspection, you’ll see some subtle differences among them in both intensity and pattern. That’s because the images capture different proteins within the complex network of synapses—and those proteins may be present in that network in different amounts and locations. Such findings may shed light on key differences among synapses, as well as provide new clues into the roles that synaptic proteins may play in schizophrenia and various other neurological disorders.

Synapses contain hundreds of proteins that regulate the release of chemicals called neurotransmitters, which allow neurons to communicate. Each synaptic protein has its own specific job in the process. But there have been longstanding technical difficulties in observing synaptic proteins at work. Conventional fluorescence microscopy can visualize at most four proteins in a synapse.

As described in Nature Communications [1], researchers led by Mark Bathe, Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), Cambridge, and Jeffrey Cottrell, Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard, Cambridge, have just upped this number considerably while delivering high quality images. They did it by adapting an existing imaging method called DNA PAINT [2]. The researchers call their adapted method PRISM. It is short for: Probe-based Imaging for Sequential Multiplexing.

Here’s how it works: First, researchers label proteins or other molecules of interest using antibodies that recognize those proteins. Those antibodies include a unique DNA probe that helps with the next important step: making the proteins visible under a microscope.

To do it, they deliver short snippets of complementary fluorescent DNA, which bind the DNA-antibody probes. While each protein of interest is imaged separately, researchers can easily wash the probes from a sample to allow a series of images to be generated, each capturing a different protein of interest.

In the original DNA PAINT, the DNA strands bind and unbind periodically to create a blinking fluorescence that can be captured using super-resolution microscopy. But that makes the process slow, requiring about half an hour for each protein.

To speed things up with PRISM, Bathe and his colleagues altered the fluorescent DNA probes. They used synthetic DNA that’s specially designed to bind more tightly or “lock” to the DNA-antibody. This gives a much brighter signal without the blinking effect. As a result, the imaging can be done faster, though at slightly lower resolution.

Though the team now captures images of 12 proteins within a sample in about an hour, this is just a start. As more DNA-antibody probes are developed for synaptic proteins, the team can readily ramp up this number to 30 protein targets.

Thanks to the BRAIN Initiative, researchers now possess a powerful new tool to study neurons. PRISM will help them learn more mechanistically about the inner workings of synapses and how they contribute to a range of neurological conditions.

References:

[1] Multiplexed and high-throughput neuronal fluorescence imaging with diffusible probes. Guo SM, Veneziano R, Gordonov S, Li L, Danielson E, Perez de Arce K, Park D, Kulesa AB, Wamhoff EC, Blainey PC, Boyden ES, Cottrell JR, Bathe M. Nat Commun. 2019 Sep 26;10(1):4377.

[2] Super-resolution microscopy with DNA-PAINT. Schnitzbauer J, Strauss MT, Schlichthaerle T, Schueder F, Jungmann R. Nat Protoc. 2017 Jun;12(6):1198-1228.

Links:

Schizophrenia (National Institute of Mental Health)

Mark Bathe (Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge)

Jeffrey Cottrell (Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard, Cambridge)

Brain Research through Advancing Innovative Neurotechnologies® (BRAIN) Initiative (NIH)

NIH Support: National Institute of Mental Health; National Human Genome Research Institute; National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke; National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences

Studies of Dogs, Mice, and People Provide Clues to OCD

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Thinkstock/wildpixel

Chances are you know someone with obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD). It’s estimated that more than 2 million Americans struggle with this mental health condition, characterized by unwanted recurring thoughts and/or repetitive behaviors, such as excessive hand washing or constant counting of objects. While we know that OCD tends to run in families, it’s been frustratingly difficult to identify specific genes that influence OCD risk.

Now, an international research team, partly funded by NIH, has made progress thanks to an innovative genomic approach involving dogs, mice, and people. The strategy allowed them to uncover four genes involved in OCD that turn out to play a role in synapses, where nerve impulses are transmitted between neurons in the brain. While more research is needed to confirm the findings and better understand the molecular mechanisms of OCD, these findings offer important new leads that could point the way to more effective treatments.

Creative Minds: Reprogramming the Brain

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

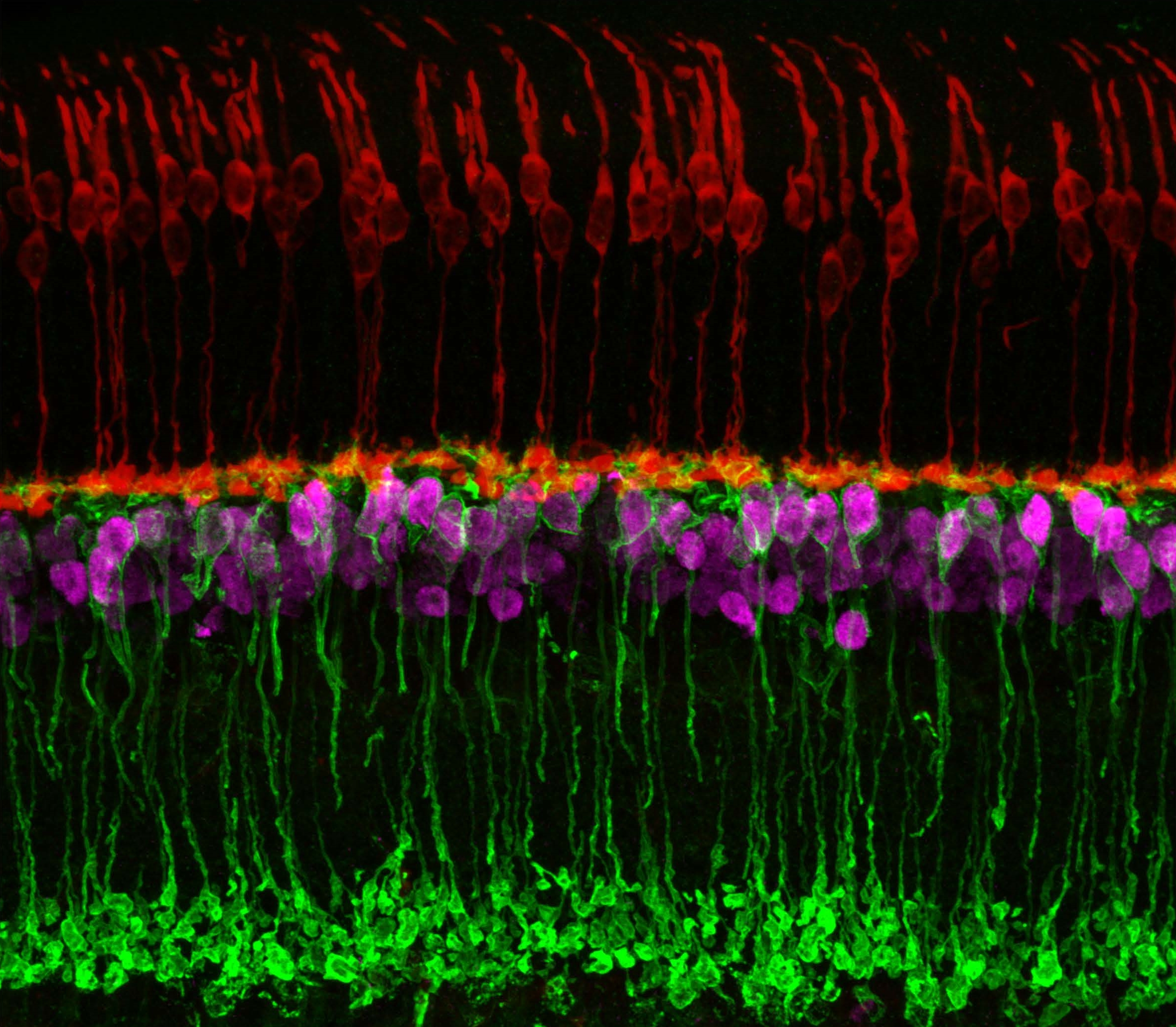

Caption: Neuronal circuits in the mouse retina. Cone photoreceptors (red) enable color vision; bipolar neurons (magenta) relay information further along the circuit; and a subtype of bipolar neuron (green) helps process signals sensed by other photoreceptors in dim light.

Credit: Brian Liu and Melanie Samuel, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston.

When most people think of reprogramming something, they probably think of writing code for a computer or typing commands into their smartphone. Melanie Samuel thinks of brain circuits, the networks of interconnected neurons that allow different parts of the brain to work together in processing information.

Samuel, a researcher at Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, wants to learn to reprogram the connections, or synapses, of brain circuits that function less well in aging and disease and limit our memory and ability to learn. She has received a 2016 NIH Director’s New Innovator Award to decipher the molecular cues that encourage the repair of damaged synapses or enable neurons to form new connections with other neurons. Because extensive synapse loss is central to most degenerative brain diseases, Samuel’s reprogramming efforts could help point the way to preventing or correcting wiring defects before they advance to serious and potentially irreversible cognitive problems.

How Sleep Resets the Brain

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Caption: Colorized 3D reconstruction of dendrites. Neurons receive input from other neurons through synapses, most of which are located along the dendrites on tiny projections called spines.

Credit: The Center for Sleep and Consciousness, University of Wisconsin-Madison School of Medicine

People spend about a third of their lives asleep. When we get too little shut-eye, it takes a toll on attention, learning and memory, not to mention our physical health. Virtually all animals with complex brains seem to have this same need for sleep. But exactly what is it about sleep that’s so essential?

Two NIH-funded studies in mice now offer a possible answer. The two research teams used entirely different approaches to reach the same conclusion: the brain’s neural connections grow stronger during waking hours, but scale back during snooze time. This sleep-related phenomenon apparently keeps neural circuits from overloading, ensuring that mice (and, quite likely humans) awaken with brains that are refreshed and ready to tackle new challenges.

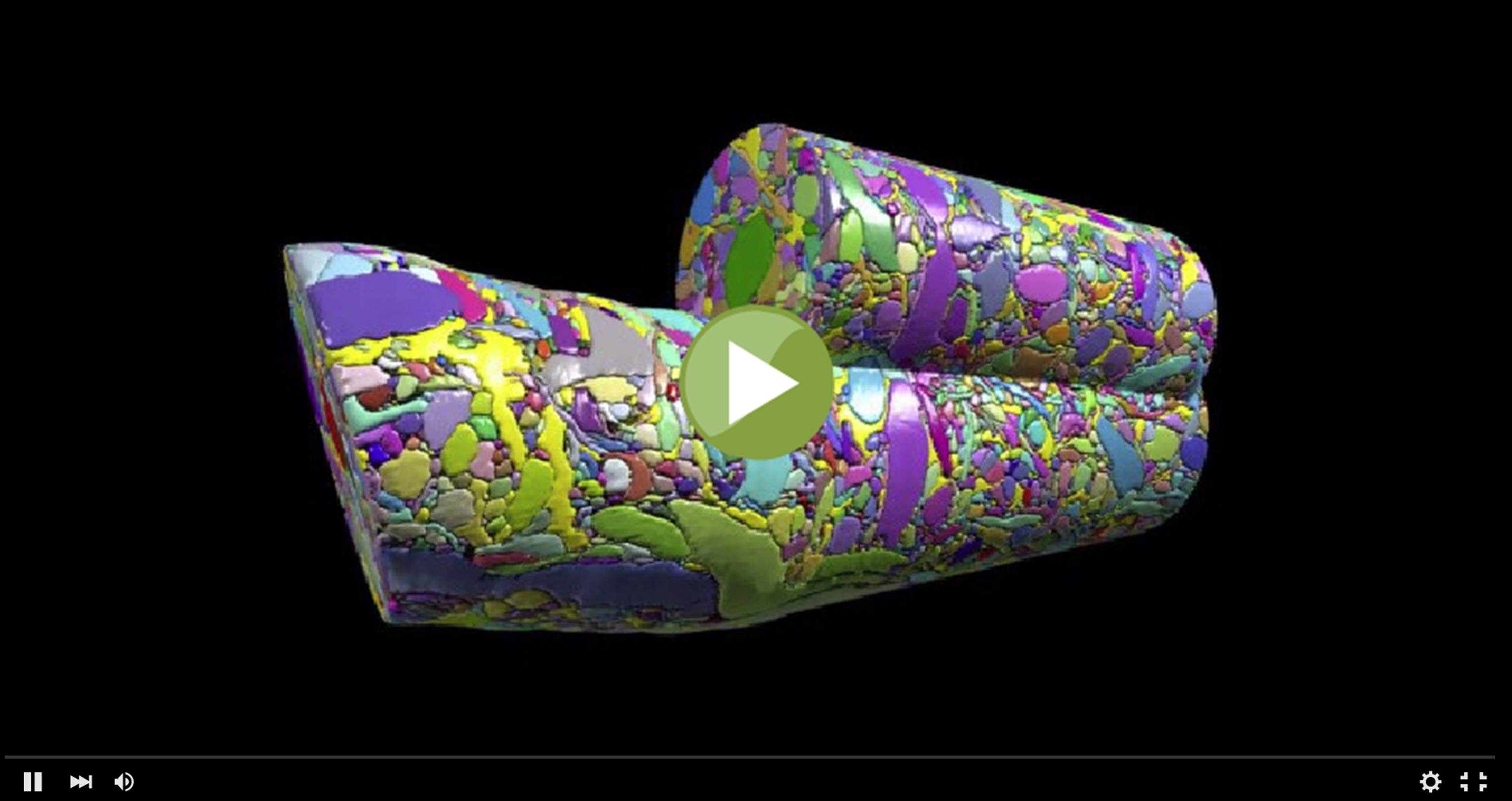

Cool Videos: Reconstructing the Cerebral Cortex

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

This colorful cylinder could pass for some sort of modern art sculpture, but it actually represents a sneak peak at some of the remarkable science that we can look forward to seeing from the Brain Research through Advancing Innovative Neurotechnologies (BRAIN) Initiative. In a recent study in the journal Cell [1], NIH grantee Jeff Lichtman of Harvard University, Cambridge, MA and his colleagues unveiled the first digitized reconstruction of tissue from the mammalian cerebral cortex—the outermost part of the brain, responsible for complex behaviors.

Specifically, Lichtman’s group mapped in exquisite detail a very small cube of a mouse’s cerebral cortex. In fact, the cube is so tiny (smaller than a grain of sand!) that it contained no whole cells, just a profoundly complex tangle of finger-like nerve cell extensions called axons and dendrites. And what you see in this video is just one cylindrical portion of that tissue sample, in which Licthtman and colleagues went full force to identify and label every single cellular and intracellular element. The message-sending axons are delineated in an array of pastel colors, while more vivid hues of red, green, and purple mark the message-receiving dendrites and bright yellow indicates the nerve-insulating glia. In total, the cylinder contains parts of about 600 axons, 40 different dendrites, and 500 synapses, where nerve impulses are transmitted between cells.