transcription factor

Gene Therapy Shows Promise Repairing Brain Tissue Damaged by Stroke

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

It’s a race against time when someone suffers a stroke caused by a blockage of a blood vessel supplying the brain. Unless clot-busting treatment is given within a few hours after symptoms appear, vast numbers of the brain’s neurons die, often leading to paralysis or other disabilities. It would be great to have a way to replace those lost neurons. Thanks to gene therapy, some encouraging strides are now being made.

In a recent study in Molecular Therapy, researchers reported that, in their mouse and rat models of ischemic stroke, gene therapy could actually convert the brain’s support cells into new, fully functional neurons [1]. Even better, after gaining the new neurons, the animals had improved motor and memory skills.

For the team led by Gong Chen, Penn State, University Park, the quest to replace lost neurons in the brain began about a decade ago. While searching for the right approach, Chen noticed other groups had learned to reprogram fibroblasts into stem cells and make replacement neural cells.

As innovative as this work was at the time, it was performed mostly in lab Petri dishes. Chen and his colleagues thought, why not reprogram cells already in the brain?

They turned their attention to the brain’s billions of supportive glial cells. Unlike neurons, glial cells divide and replicate. They also are known to survive and activate following a brain injury, remaining at the wound and ultimately forming a scar. This same process had also been observed in the brain following many types of injury, including stroke and neurodegenerative conditions such as Alzheimer’s disease.

To Chen’s NIH-supported team, it looked like glial cells might be a perfect target for gene therapies to replace lost neurons. As reported about five years ago, the researchers were on the right track [2].

The Chen team showed it was possible to reprogram glial cells in the brain into functional neurons. They succeeded using a genetically engineered retrovirus that delivered a single protein called NeuroD1. It’s a neural transcription factor that switches genes on and off in neural cells and helps to determine their cell fate. The newly generated neurons were also capable of integrating into brain circuits to repair damaged tissue.

There was one major hitch: the NeuroD1 retroviral vector only reprogrammed actively dividing glial cells. That suggested their strategy likely couldn’t generate the large numbers of new cells needed to repair damaged brain tissue following a stroke.

Fast-forward a couple of years, and improved adeno-associated viral vectors (AAV) have emerged as a major alternative to retroviruses for gene therapy applications. This was exactly the breakthrough that the Chen team needed. The AAVs can reprogram glial cells whether they are dividing or not.

In the new study, Chen’s team, led by post-doc Yu-Chen Chen, put this new gene therapy system to work, and the results are quite remarkable. In a mouse model of ischemic stroke, the researchers showed the treatment could regenerate about a third of the total lost neurons by preferentially targeting reactive, scar-forming glial cells. The conversion of those reactive glial cells into neurons also protected another third of the neurons from injury.

Studies in brain slices showed that the replacement neurons were fully functional and appeared to have made the needed neural connections in the brain. Importantly, their studies also showed that the NeuroD1 gene therapy led to marked improvements in the functional recovery of the mice after a stroke.

In fact, several tests of their ability to make fine movements with their forelimbs showed about a 60 percent improvement within 20 to 60 days of receiving the NeuroD1 therapy. Together with study collaborator and NIH grantee Gregory Quirk, University of Puerto Rico, San Juan, they went on to show similar improvements in the ability of rats to recover from stroke-related deficits in memory.

While further study is needed, the findings in rodents offer encouraging evidence that treatments to repair the brain after a stroke or other injury may be on the horizon. In the meantime, the best strategy for limiting the number of neurons lost due to stroke is to recognize the signs and get to a well-equipped hospital or call 911 right away if you or a loved one experience them. Those signs include: sudden numbness or weakness of one side of the body; confusion; difficulty speaking, seeing, or walking; and a sudden, severe headache with unknown causes. Getting treatment for this kind of “brain attack” within four hours of the onset of symptoms can make all the difference in recovery.

References:

[1] A NeuroD1 AAV-Based gene therapy for functional brain repair after ischemic injury through in vivo astrocyte-to-neuron conversion. Chen Y-C et al. Molecular Therapy. Published online September 6, 2019.

[2] In vivo direct reprogramming of reactive glial cells into functional neurons after brain injury and in an Alzheimer’s disease model. Guo Z, Zhang L, Wu Z, Chen Y, Wang F, Chen G. Cell Stem Cell. 2014 Feb 6;14(2):188-202.

Links:

Stroke (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute/NIH)

Gene Therapy (National Human Genome Research Institute/NIH)

Chen Lab (Penn State, University Park)

NIH Support: National Institute on Aging; National Institute of Mental Health

Creative Minds: Using Machine Learning to Understand Genome Function

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Science has always fascinated Anshul Kundaje, whether it was biology, physics, or chemistry. When he left his home country of India to pursue graduate studies in electrical engineering at Columbia University, New York, his plan was to focus on telecommunications and computer networks. But a course in computational genomics during his first semester showed him he could follow his interest in computing without giving up his love for biology.

Now an assistant professor of genetics and computer science at Stanford University, Palo Alto, CA, Kundaje has received a 2016 NIH Director’s New Innovator Award to explore not just how the human genome sequence encodes function, but also why it functions in the way that it does. Kundaje even envisions a time when it might be possible to use sophisticated computational approaches to predict the genomic basis of many human diseases.

Creative Minds: Mapping the Biocircuitry of Schizophrenia and Bipolar Disorder

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

As a graduate student in the 1980s, Bruce Yankner wondered what if cancer-causing genes switched on in non-dividing neurons of the brain. Rather than form a tumor, would those genes cause neurons to degenerate? To explore such what-ifs, Yankner spent his days tinkering with neural cells, using viruses to insert various mutant genes and study their effects. In a stroke of luck, one of Yankner’s insertions encoded a precursor to a protein called amyloid. Those experiments and later ones from Yankner’s own lab showed definitively that high concentrations of amyloid, as found in the brains of people with Alzheimer’s disease, are toxic to neural cells [1].

The discovery set Yankner on a career path to study normal changes in the aging human brain and their connection to neurodegenerative diseases. At Harvard Medical School, Boston, Yankner and his colleague George Church are now recipients of an NIH Director’s 2016 Transformative Research Award to apply what they’ve learned about the aging brain to study changes in the brains of younger people with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, two poorly understood psychiatric disorders.

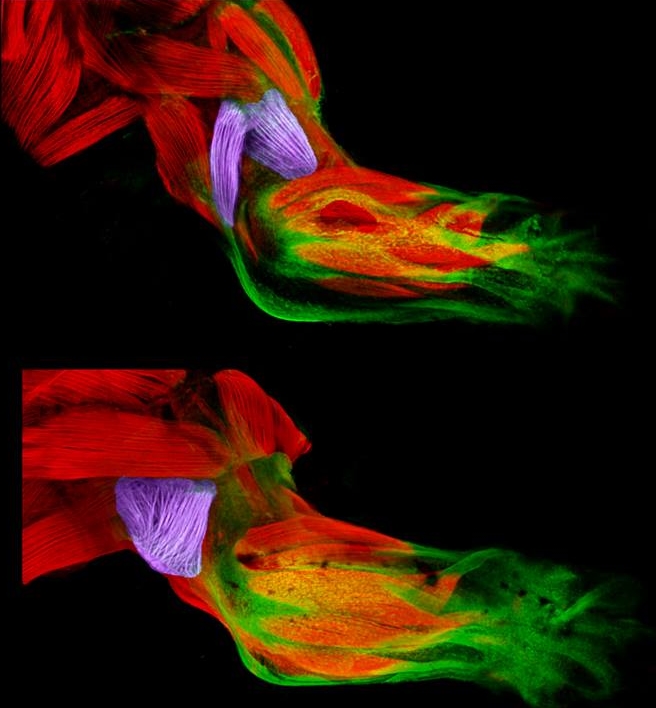

Snapshots of Life: Muscling in on Development

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Twice a week, I do an hour of weight training to maintain muscle strength and tone. Millions of Americans do the same, and there’s always a lot of attention paid to those upper arm muscles—the biceps and triceps. Less appreciated is another arm muscle that pumps right along during workouts: the brachialis. This muscle—located under the biceps—helps your elbow flex when you are doing all kinds of things, whether curling a 50-pound barbell or just grabbing a bag of groceries or your luggage out of the car.

Now, scientific studies of the triceps and brachialis are providing important clues about how the body’s 40 different types of limb muscles assume their distinct identities during development [1]. In these images from the NIH-supported lab of Gabrielle Kardon at the University of Utah, Salt Lake City, you see the developing forelimb of a healthy mouse strain (top) compared to that of a mutant mouse strain with a stiff, abnormal gait (bottom).

Molecular Answers Found for a Mysterious Rare Immune Disorder

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Caption: Helping to solve a medical mystery. Top left, University of Utah’s Harry Hill; Bottom, CVID patient Roma Jean Ockler; Right, Ockler showing the medication that helps to control her CVID.

Credit: Jeffrey Allred, Deseret News

When most of us come down with a bacterial infection, we generally bounce back with appropriate treatment in a matter of days. But that’s often not the case for people who suffer from common variable immunodeficiency (CVID), a group of rare disorders that increase the risk of life-threatening bacterial infections of the lungs, sinuses, and intestines. CVID symptoms typically arise in adulthood and often take many years to diagnose and treat, in part because its exact molecular causes are unknown in most individuals.

Now, by combining the latest in genomic technology with some good, old-fashioned medical detective work, NIH-funded researchers have pinpointed the genetic mutation responsible for an inherited subtype of CVID characterized by the loss of immune cells essential to the normal production of antibodies [1]. This discovery, reported recently in The New England Journal of Medicine, makes it possible at long last to provide a definitive diagnosis for people with this CVID subtype, paving the way for them to receive more precise medical treatment and care. More broadly, the new study demonstrates the power of precision medicine approaches to help the estimated 25 to 30 million Americans who live with rare diseases [2].

A New Tool in the Toolbox: New Method Traces Free-Floating DNA Back to Its Source

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Caption: DNA (blue) loops around nucleosomes (gray) and is bound by transcription factors (red), proteins that switch genes on and off and act in a tissue-specific manner. When cells die, enzymes (scissors) chop up areas between the nucleosomes and transcription factors, releasing DNA fragments in unique patterns. By gathering the released DNA fragments in blood, researchers can tell which types of cells produced them.

Credit: Shendure Lab/University of Washington

When cells die, scissor-like enzymes snip their DNA into tiny fragments that leak into the bloodstream and other bodily fluids. Researchers have been busy in recent years working on ways to collect these free-floating bits of DNA and explore their potential use in clinical care.

These approaches, sometimes referred to as “liquid biopsies,” hinge on the ability to distinguish specific DNA fragments from the body’s normal background of “cell-free” DNA, most of which comes from dying white blood cells. Seeking other sources for cell-free DNA in particular situations is beginning to bear fruit, however. Current applications include: 1) a test in maternal blood to look for DNA from the fetus (actually from the fetal component of the placenta), which provides a means of detecting a possible genetic abnormality; 2) a test in a cancer patient’s blood to look for cancer-specific mutations, as a way of assessing response to treatment or early signs of relapse; and 3) a test in an organ transplant recipient, where increasing abundance of DNA fragments from the donor can be an early sign of rejection.

But recent proposals have been floated about looking for cell-free DNA in healthy individuals, as an early sign of some health problems. Suppose something was found—how could you know the source? Now a team of NIH-funded researchers has devised a new method that uses distinctive features of DNA packaging to provide an additional layer of information about the origins of free-floating DNA, vastly expanding the potential uses for such tests [1].

Snapshots of Life: The Dance of Development

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

| Credit: Amanda L. Zacharias and John I. Murray, Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania |

This video may look like an aerial shot of a folk dance: first a lone dancer, then two, then four, until finally dozens upon dozens of twirling orbs pack the space in a frenzy of motion. But what you’re actually viewing is an action shot of one of biology’s most valuable models for studying development: the round worm, Caenorhabditis elegans (C. elegans).

Taking advantage of time-lapse technology, this video packs into 38 seconds the first 13 hours of this tiny worm’s life, showing its development from a single cell into the larval, or juvenile stage, with 558 cells. (If you are wondering why C. elegans doesn’t look very worm-like at the end of this video, it’s because the organism develops curled up inside a transparent shell—and after it breaks out of that shell, it squirms quickly away.)