adeno-associated virus

Encouraging News on Gene Therapy for Hemophilia A

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

About 20,000 people in the U.S. live with hemophilia A. It’s a rare X-linked genetic disorder that affects predominantly males and causes their blood to clot poorly when healing wounds. For some, routine daily activities can turn into painful medical emergencies to stop internal bleeding, all because of changes in a single gene that disables an essential clotting protein.

Now, results of an early-stage clinical trial, published recently in the New England Journal of Medicine, demonstrate that gene therapy is within reach to produce the essential clotting factor in people with hemophilia A. The results show that, in most of the 18 adult participants, a refined gene therapy strategy produced lasting expression of factor VIII (FVIII), the missing clotting factor in hemophilia A [1]. In fact, gene therapy helped most participants reduce—or, in some cases, completely eliminate—bleeding events.

Currently, the most-common treatment option for males with hemophilia A is intravenous infusion of FVIII concentrate. Though infused FVIII becomes immediately available in the bloodstream, these treatments aren’t a cure and must be repeated, often weekly or every other day, to prevent or control bleeding.

Gene therapy, however, represents a possible cure for hemophilia A. Earlier clinical trials reported some success using benign adeno-associated viruses (AAVs) as the vector to deliver the therapeutic FVIII gene to cells in the liver, where the clotting protein is made. But after a year, those trial participants had a marked decline in FVIII expression. Follow-up studies then found that the decline continued over time, thought to be at least in part because of an immune response to the AAV vector.

In the new study, an NIH-funded team led by Lindsey George and Katherine High of the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia and the University of Pennsylvania, tested their refined delivery system. High is also currently with Asklepios BioPharmaceutical, Inc., Chapel Hill, NC. (Back in the 1970s, she and I were medical students in the same class at the University of North Carolina.) The study was also supported by Spark Therapeutics, Philadelphia.

Trial participants received a single infusion of the novel recombinant AAV-based gene therapy called SPK-8011. It is specifically designed to produce FVIII expression in the liver. In this phase 1/2 clinical trial, which evaluates the safety and initial efficacy of a treatment, participants received one of four different doses of SPK-8011. Most also received steroids to prevent or treat the presumed counterproductive immune response to the therapy.

The researchers followed participants for a year after the experimental treatment, and all enrolled in a follow-up trial for continued observation. During this time, researchers detected no major safety concerns, though several patients had increases in blood levels of a liver enzyme.

The great news is all participants produced the missing FVIII after gene therapy. Twelve of the 16 participants were followed for more than two years and had no apparent decrease in clotting factor activity. This is especially noteworthy because it offers the first demonstration of multiyear stable and durable FVIII expression in individuals with hemophilia A following gene transfer.

Even more encouraging, the men in the trial had more than a 92 percent reduction in bleeding episodes on average. Before treatment, most of the men had 8.5 bleeding episodes per year. After treatment, those events dropped to an average of less than one per year. However, two study participants lost FVIII expression within a year of treatment, presumably due to an immune response to the therapeutic AAV. This finding shows that, while steroids help, they don’t always prevent loss of a therapeutic gene’s expression.

Overall, the findings suggest that AAV-based gene therapy can lead to the durable production of FVIII over several years and significantly reduce bleeding events. The researchers are now exploring possibly more effective ways to control the immune response to AAV in expansion of this phase 1/2 investigation before pursuing a larger phase 3 trial. They’re continuing to monitor participants closely to establish safety and efficacy in the months and years to come.

On a related note, the recently announced Bespoke Gene Therapy Consortium (BGTC), a partnership between NIH and industry, will expand the refined gene therapy approach demonstrated here to more rare and ultrarare diseases. That should make these latest findings extremely encouraging news for the millions of people born with other rare genetic conditions caused by known alterations to a single gene.

Reference:

[1] Multiyear Factor VIII expression after AAV Gene transfer for Hemophilia A. George LA, Monahan PE, Eyster ME, Sullivan SK, Ragni MV, Croteau SE, Rasko JEJ, Recht M, Samelson-Jones BJ, MacDougall A, Jaworski K, Noble R, Curran M, Kuranda K, Mingozzi F, Chang T, Reape KZ, Anguela XM, High KA. N Engl J Med. 2021 Nov 18;385(21):1961-1973.

Links:

Hemophilia A (National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences/NIH)

FAQ About Rare Diseases (National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences/NIH)

Bespoke Gene Therapy Consortium (BGTC) (NIH)

Accelerating Medicines Partnership® (AMP®) (NIH)

Lindsey George (University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia)

Katherine High (University of Pennsylvania)

NIH Support: National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute

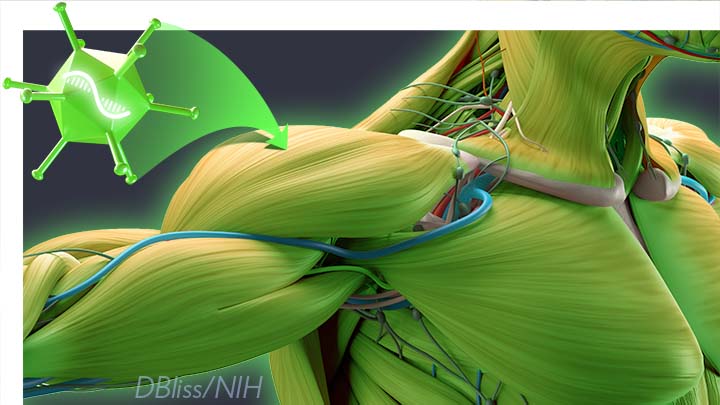

Engineering a Better Way to Deliver Therapeutic Genes to Muscles

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Amid all the progress toward ending the COVID-19 pandemic, it’s worth remembering that researchers here and around the world continue to make important advances in tackling many other serious health conditions. As an inspiring NIH-supported example, I’d like to share an advance on the use of gene therapy for treating genetic diseases that progressively degenerate muscle, such as Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD).

As published recently in the journal Cell, researchers have developed a promising approach to deliver therapeutic genes and gene editing tools to muscle more efficiently, thus requiring lower doses [1]. In animal studies, the new approach has targeted muscle far more effectively than existing strategies. It offers an exciting way forward to reduce unwanted side effects from off-target delivery, which has hampered the development of gene therapy for many conditions.

In boys born with DMD (it’s an X-linked disease and therefore affects males), skeletal and heart muscles progressively weaken due to mutations in a gene encoding a critical muscle protein called dystrophin. By age 10, most boys require a wheelchair. Sadly, their life expectancy remains less than 30 years.

The hope is gene therapies will one day treat or even cure DMD and allow people with the disease to live longer, high-quality lives. Unfortunately, the benign adeno-associated viruses (AAVs) traditionally used to deliver the healthy intact dystrophin gene into cells mostly end up in the liver—not in muscles. It’s also the case for gene therapy of many other muscle-wasting genetic diseases.

The heavy dose of viral vector to the liver is not without concern. Recently and tragically, there have been deaths in a high-dose AAV gene therapy trial for X-linked myotubular myopathy (XLMTM), a different disorder of skeletal muscle in which there may already be underlying liver disease, potentially increasing susceptibility to toxicity.

To correct this concerning routing error, researchers led by Mohammadsharif Tabebordbar in the lab of Pardis Sabeti, Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard and Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, have now assembled an optimized collection of AAVs. They have been refined to be about 10 times better at reaching muscle fibers than those now used in laboratory studies and clinical trials. In fact, researchers call them myotube AAVs, or MyoAAVs.

MyoAAVs can deliver therapeutic genes to muscle at much lower doses—up to 250 times lower than what’s needed with traditional AAVs. While this approach hasn’t yet been tried in people, animal studies show that MyoAAVs also largely avoid the liver, raising the prospect for more effective gene therapies without the risk of liver damage and other serious side effects.

In the Cell paper, the researchers demonstrate how they generated MyoAAVs, starting out with the commonly used AAV9. Their goal was to modify the outer protein shell, or capsid, to create an AAV that would be much better at specifically targeting muscle. To do so, they turned to their capsid engineering platform known as, appropriately enough, DELIVER. It’s short for Directed Evolution of AAV capsids Leveraging In Vivo Expression of transgene RNA.

Here’s how DELIVER works. The researchers generate millions of different AAV capsids by adding random strings of amino acids to the portion of the AAV9 capsid that binds to cells. They inject those modified AAVs into mice and then sequence the RNA from cells in muscle tissue throughout the body. The researchers want to identify AAVs that not only enter muscle cells but that also successfully deliver therapeutic genes into the nucleus to compensate for the damaged version of the gene.

This search delivered not just one AAV—it produced several related ones, all bearing a unique surface structure that enabled them specifically to target muscle cells. Then, in collaboration with Amy Wagers, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, the team tested their MyoAAV toolset in animal studies.

The first cargo, however, wasn’t a gene. It was the gene-editing system CRISPR-Cas9. The team found the MyoAAVs correctly delivered the gene-editing system to muscle cells and also repaired dysfunctional copies of the dystrophin gene better than the CRISPR cargo carried by conventional AAVs. Importantly, the muscles of MyoAAV-treated animals also showed greater strength and function.

Next, the researchers teamed up with Alan Beggs, Boston Children’s Hospital, and found that MyoAAV was effective in treating mouse models of XLMTM. This is the very condition mentioned above, in which very high dose gene therapy with a current AAV vector has led to tragic outcomes. XLMTM mice normally die in 10 weeks. But, after receiving MyoAAV carrying a corrective gene, all six mice had a normal lifespan. By comparison, mice treated in the same way with traditional AAV lived only up to 21 weeks of age. What’s more, the researchers used MyoAAV at a dose 100 times lower than that currently used in clinical trials.

While further study is needed before this approach can be tested in people, MyoAAV was also used to successfully introduce therapeutic genes into human cells in the lab. This suggests that the early success in animals might hold up in people. The approach also has promise for developing AAVs with potential for targeting other organs, thereby possibly providing treatment for a wide range of genetic conditions.

The new findings are the result of a decade of work from Tabebordbar, the study’s first author. His tireless work is also personal. His father has a rare genetic muscle disease that has put him in a wheelchair. With this latest advance, the hope is that the next generation of promising gene therapies might soon make its way to the clinic to help Tabebordbar’s father and so many other people.

Reference:

[1] Directed evolution of a family of AAV capsid variants enabling potent muscle-directed gene delivery across species. Tabebordbar M, Lagerborg KA, Stanton A, King EM, Ye S, Tellez L, Krunnfusz A, Tavakoli S, Widrick JJ, Messemer KA, Troiano EC, Moghadaszadeh B, Peacker BL, Leacock KA, Horwitz N, Beggs AH, Wagers AJ, Sabeti PC. Cell. 2021 Sep 4:S0092-8674(21)01002-3.

Links:

Muscular Dystrophy Information Page (National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke/NIH)

X-linked myotubular myopathy (Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center/National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences/NIH)

Somatic Cell Genome Editing (Common Fund/NIH)

Mohammadsharif Tabebordbar (Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard and Harvard University, Cambridge, MA)

Sabeti Lab (Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard and Harvard University)

NIH Support: Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development; Common Fund

Gene Therapy Shows Promise Repairing Brain Tissue Damaged by Stroke

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

It’s a race against time when someone suffers a stroke caused by a blockage of a blood vessel supplying the brain. Unless clot-busting treatment is given within a few hours after symptoms appear, vast numbers of the brain’s neurons die, often leading to paralysis or other disabilities. It would be great to have a way to replace those lost neurons. Thanks to gene therapy, some encouraging strides are now being made.

In a recent study in Molecular Therapy, researchers reported that, in their mouse and rat models of ischemic stroke, gene therapy could actually convert the brain’s support cells into new, fully functional neurons [1]. Even better, after gaining the new neurons, the animals had improved motor and memory skills.

For the team led by Gong Chen, Penn State, University Park, the quest to replace lost neurons in the brain began about a decade ago. While searching for the right approach, Chen noticed other groups had learned to reprogram fibroblasts into stem cells and make replacement neural cells.

As innovative as this work was at the time, it was performed mostly in lab Petri dishes. Chen and his colleagues thought, why not reprogram cells already in the brain?

They turned their attention to the brain’s billions of supportive glial cells. Unlike neurons, glial cells divide and replicate. They also are known to survive and activate following a brain injury, remaining at the wound and ultimately forming a scar. This same process had also been observed in the brain following many types of injury, including stroke and neurodegenerative conditions such as Alzheimer’s disease.

To Chen’s NIH-supported team, it looked like glial cells might be a perfect target for gene therapies to replace lost neurons. As reported about five years ago, the researchers were on the right track [2].

The Chen team showed it was possible to reprogram glial cells in the brain into functional neurons. They succeeded using a genetically engineered retrovirus that delivered a single protein called NeuroD1. It’s a neural transcription factor that switches genes on and off in neural cells and helps to determine their cell fate. The newly generated neurons were also capable of integrating into brain circuits to repair damaged tissue.

There was one major hitch: the NeuroD1 retroviral vector only reprogrammed actively dividing glial cells. That suggested their strategy likely couldn’t generate the large numbers of new cells needed to repair damaged brain tissue following a stroke.

Fast-forward a couple of years, and improved adeno-associated viral vectors (AAV) have emerged as a major alternative to retroviruses for gene therapy applications. This was exactly the breakthrough that the Chen team needed. The AAVs can reprogram glial cells whether they are dividing or not.

In the new study, Chen’s team, led by post-doc Yu-Chen Chen, put this new gene therapy system to work, and the results are quite remarkable. In a mouse model of ischemic stroke, the researchers showed the treatment could regenerate about a third of the total lost neurons by preferentially targeting reactive, scar-forming glial cells. The conversion of those reactive glial cells into neurons also protected another third of the neurons from injury.

Studies in brain slices showed that the replacement neurons were fully functional and appeared to have made the needed neural connections in the brain. Importantly, their studies also showed that the NeuroD1 gene therapy led to marked improvements in the functional recovery of the mice after a stroke.

In fact, several tests of their ability to make fine movements with their forelimbs showed about a 60 percent improvement within 20 to 60 days of receiving the NeuroD1 therapy. Together with study collaborator and NIH grantee Gregory Quirk, University of Puerto Rico, San Juan, they went on to show similar improvements in the ability of rats to recover from stroke-related deficits in memory.

While further study is needed, the findings in rodents offer encouraging evidence that treatments to repair the brain after a stroke or other injury may be on the horizon. In the meantime, the best strategy for limiting the number of neurons lost due to stroke is to recognize the signs and get to a well-equipped hospital or call 911 right away if you or a loved one experience them. Those signs include: sudden numbness or weakness of one side of the body; confusion; difficulty speaking, seeing, or walking; and a sudden, severe headache with unknown causes. Getting treatment for this kind of “brain attack” within four hours of the onset of symptoms can make all the difference in recovery.

References:

[1] A NeuroD1 AAV-Based gene therapy for functional brain repair after ischemic injury through in vivo astrocyte-to-neuron conversion. Chen Y-C et al. Molecular Therapy. Published online September 6, 2019.

[2] In vivo direct reprogramming of reactive glial cells into functional neurons after brain injury and in an Alzheimer’s disease model. Guo Z, Zhang L, Wu Z, Chen Y, Wang F, Chen G. Cell Stem Cell. 2014 Feb 6;14(2):188-202.

Links:

Stroke (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute/NIH)

Gene Therapy (National Human Genome Research Institute/NIH)

Chen Lab (Penn State, University Park)

NIH Support: National Institute on Aging; National Institute of Mental Health

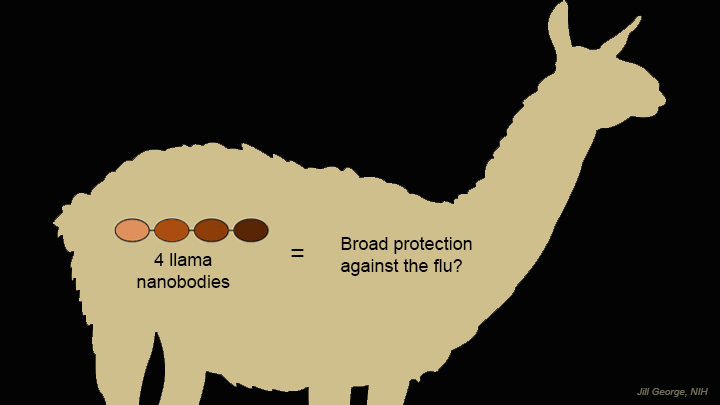

Looking to Llamas for New Ways to Fight the Flu

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Researchers are making tremendous strides toward developing better ways to reduce our risk of getting the flu. And one of the latest ideas for foiling the flu—a “gene mist” that could be sprayed into the nose—comes from a most surprising source: llamas.

Researchers are making tremendous strides toward developing better ways to reduce our risk of getting the flu. And one of the latest ideas for foiling the flu—a “gene mist” that could be sprayed into the nose—comes from a most surprising source: llamas.

Like humans and many other creatures, these fuzzy South American relatives of the camel produce immune molecules, called antibodies, in their blood when exposed to viruses and other foreign substances. Researchers speculated that because the llama’s antibodies are so much smaller than human antibodies, they might be easier to use therapeutically in fending off a wide range of flu viruses. This idea is now being leveraged to design a new type of gene therapy that may someday provide humans with broader protection against the flu [1].