rare diseases

Engineering a Better Way to Deliver Therapeutic Genes to Muscles

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Amid all the progress toward ending the COVID-19 pandemic, it’s worth remembering that researchers here and around the world continue to make important advances in tackling many other serious health conditions. As an inspiring NIH-supported example, I’d like to share an advance on the use of gene therapy for treating genetic diseases that progressively degenerate muscle, such as Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD).

As published recently in the journal Cell, researchers have developed a promising approach to deliver therapeutic genes and gene editing tools to muscle more efficiently, thus requiring lower doses [1]. In animal studies, the new approach has targeted muscle far more effectively than existing strategies. It offers an exciting way forward to reduce unwanted side effects from off-target delivery, which has hampered the development of gene therapy for many conditions.

In boys born with DMD (it’s an X-linked disease and therefore affects males), skeletal and heart muscles progressively weaken due to mutations in a gene encoding a critical muscle protein called dystrophin. By age 10, most boys require a wheelchair. Sadly, their life expectancy remains less than 30 years.

The hope is gene therapies will one day treat or even cure DMD and allow people with the disease to live longer, high-quality lives. Unfortunately, the benign adeno-associated viruses (AAVs) traditionally used to deliver the healthy intact dystrophin gene into cells mostly end up in the liver—not in muscles. It’s also the case for gene therapy of many other muscle-wasting genetic diseases.

The heavy dose of viral vector to the liver is not without concern. Recently and tragically, there have been deaths in a high-dose AAV gene therapy trial for X-linked myotubular myopathy (XLMTM), a different disorder of skeletal muscle in which there may already be underlying liver disease, potentially increasing susceptibility to toxicity.

To correct this concerning routing error, researchers led by Mohammadsharif Tabebordbar in the lab of Pardis Sabeti, Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard and Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, have now assembled an optimized collection of AAVs. They have been refined to be about 10 times better at reaching muscle fibers than those now used in laboratory studies and clinical trials. In fact, researchers call them myotube AAVs, or MyoAAVs.

MyoAAVs can deliver therapeutic genes to muscle at much lower doses—up to 250 times lower than what’s needed with traditional AAVs. While this approach hasn’t yet been tried in people, animal studies show that MyoAAVs also largely avoid the liver, raising the prospect for more effective gene therapies without the risk of liver damage and other serious side effects.

In the Cell paper, the researchers demonstrate how they generated MyoAAVs, starting out with the commonly used AAV9. Their goal was to modify the outer protein shell, or capsid, to create an AAV that would be much better at specifically targeting muscle. To do so, they turned to their capsid engineering platform known as, appropriately enough, DELIVER. It’s short for Directed Evolution of AAV capsids Leveraging In Vivo Expression of transgene RNA.

Here’s how DELIVER works. The researchers generate millions of different AAV capsids by adding random strings of amino acids to the portion of the AAV9 capsid that binds to cells. They inject those modified AAVs into mice and then sequence the RNA from cells in muscle tissue throughout the body. The researchers want to identify AAVs that not only enter muscle cells but that also successfully deliver therapeutic genes into the nucleus to compensate for the damaged version of the gene.

This search delivered not just one AAV—it produced several related ones, all bearing a unique surface structure that enabled them specifically to target muscle cells. Then, in collaboration with Amy Wagers, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, the team tested their MyoAAV toolset in animal studies.

The first cargo, however, wasn’t a gene. It was the gene-editing system CRISPR-Cas9. The team found the MyoAAVs correctly delivered the gene-editing system to muscle cells and also repaired dysfunctional copies of the dystrophin gene better than the CRISPR cargo carried by conventional AAVs. Importantly, the muscles of MyoAAV-treated animals also showed greater strength and function.

Next, the researchers teamed up with Alan Beggs, Boston Children’s Hospital, and found that MyoAAV was effective in treating mouse models of XLMTM. This is the very condition mentioned above, in which very high dose gene therapy with a current AAV vector has led to tragic outcomes. XLMTM mice normally die in 10 weeks. But, after receiving MyoAAV carrying a corrective gene, all six mice had a normal lifespan. By comparison, mice treated in the same way with traditional AAV lived only up to 21 weeks of age. What’s more, the researchers used MyoAAV at a dose 100 times lower than that currently used in clinical trials.

While further study is needed before this approach can be tested in people, MyoAAV was also used to successfully introduce therapeutic genes into human cells in the lab. This suggests that the early success in animals might hold up in people. The approach also has promise for developing AAVs with potential for targeting other organs, thereby possibly providing treatment for a wide range of genetic conditions.

The new findings are the result of a decade of work from Tabebordbar, the study’s first author. His tireless work is also personal. His father has a rare genetic muscle disease that has put him in a wheelchair. With this latest advance, the hope is that the next generation of promising gene therapies might soon make its way to the clinic to help Tabebordbar’s father and so many other people.

Reference:

[1] Directed evolution of a family of AAV capsid variants enabling potent muscle-directed gene delivery across species. Tabebordbar M, Lagerborg KA, Stanton A, King EM, Ye S, Tellez L, Krunnfusz A, Tavakoli S, Widrick JJ, Messemer KA, Troiano EC, Moghadaszadeh B, Peacker BL, Leacock KA, Horwitz N, Beggs AH, Wagers AJ, Sabeti PC. Cell. 2021 Sep 4:S0092-8674(21)01002-3.

Links:

Muscular Dystrophy Information Page (National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke/NIH)

X-linked myotubular myopathy (Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center/National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences/NIH)

Somatic Cell Genome Editing (Common Fund/NIH)

Mohammadsharif Tabebordbar (Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard and Harvard University, Cambridge, MA)

Sabeti Lab (Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard and Harvard University)

NIH Support: Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development; Common Fund

Seeing the Cytoskeleton in a Whole New Light

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

It’s been 25 years since researchers coaxed a bacterium to synthesize an unusual jellyfish protein that fluoresced bright green when irradiated with blue light. Within months, another group had also fused this small green fluorescent protein (GFP) to larger proteins to make their whereabouts inside the cell come to light—like never before.

To mark the anniversary of this Nobel Prize-winning work and show off the rainbow of color that is now being used to illuminate the inner workings of the cell, the American Society for Cell Biology (ASCB) recently held its Green Fluorescent Protein Image and Video Contest. Over the next few months, my blog will feature some of the most eye-catching entries—starting with this video that will remind those who grew up in the 1980s of those plasma balls that, when touched, light up with a simulated bolt of colorful lightning.

This video, which took third place in the ASCB contest, shows the cytoskeleton of a frequently studied human breast cancer cell line. The cytoskeleton is made from protein structures called microtubules, made visible by fluorescently tagging a protein called doublecortin (orange). Filaments of another protein called actin (purple) are seen here as the fine meshwork in the cell periphery.

The cytoskeleton plays an important role in giving cells shape and structure. But it also allows a cell to move and divide. Indeed, the motion in this video shows that the complex network of cytoskeletal components is constantly being organized and reorganized in ways that researchers are still working hard to understand.

Jeffrey van Haren, Erasmus University Medical Center, Rotterdam, the Netherlands, shot this video using the tools of fluorescence microscopy when he was a postdoctoral researcher in the NIH-funded lab of Torsten Wittman, University of California, San Francisco.

All good movies have unusual plot twists, and that’s truly the case here. Though the researchers are using a breast cancer cell line, their primary interest is in the doublecortin protein, which is normally found in association with microtubules in the developing brain. In fact, in people with mutations in the gene that encodes this protein, neurons fail to migrate properly during development. The resulting condition, called lissencephaly, leads to epilepsy, cognitive disability, and other neurological problems.

Cancer cells don’t usually express doublecortin. But, in some of their initial studies, the Wittman team thought it would be much easier to visualize and study doublecortin in the cancer cells. And so, the researchers tagged doublecortin with an orange fluorescent protein, engineered its expression in the breast cancer cells, and van Haren started taking pictures.

This movie and others helped lead to the intriguing discovery that doublecortin binds to microtubules in some places and not others [1]. It appears to do so based on the ability to recognize and bind to certain microtubule geometries. The researchers have since moved on to studies in cultured neurons.

This video is certainly a good example of the illuminating power of fluorescent proteins: enabling us to see cells and their cytoskeletons as incredibly dynamic, constantly moving entities. And, if you’d like to see much more where this came from, consider visiting van Haren’s Twitter gallery of microtubule videos here:

Reference:

[1] Doublecortin is excluded from growing microtubule ends and recognizes the GDP-microtubule lattice. Ettinger A, van Haren J, Ribeiro SA, Wittmann T. Curr Biol. 2016 Jun 20;26(12):1549-1555.

Links:

Lissencephaly Information Page (National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke/NIH)

Wittman Lab (University of California, San Francisco)

Green Fluorescent Protein Image and Video Contest (American Society for Cell Biology, Bethesda, MD)

NIH Support: National Institute of General Medical Sciences

Whole-Genome Sequencing Plus AI Yields Same-Day Genetic Diagnoses

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Back in April 2003, when the international Human Genome Project successfully completed the first reference sequence of the human DNA blueprint, we were thrilled to have achieved that feat in just 13 years. Sure, the U.S. contribution to that first human reference sequence cost an estimated $400 million, but we knew (or at least we hoped) that the costs would come down quickly, and the speed would accelerate. How far we’ve come since then! A new study shows that whole genome sequencing—combined with artificial intelligence (AI)—can now be used to diagnose genetic diseases in seriously ill babies in less than 24 hours.

Take a moment to absorb this. I would submit that there is no other technology in the history of planet Earth that has experienced this degree of progress in speed and affordability. And, at the same time, DNA sequence technology has achieved spectacularly high levels of accuracy. The time-honored adage that you can only get two out of three for “faster, better, and cheaper” has been broken—all three have been dramatically enhanced by the advances of the last 16 years.

Rapid diagnosis is critical for infants born with mysterious conditions because it enables them to receive potentially life-saving interventions as soon as possible after birth. In a study in Science Translational Medicine, NIH-funded researchers describe development of a highly automated, genome-sequencing pipeline that’s capable of routinely delivering a diagnosis to anxious parents and health-care professionals dramatically earlier than typically has been possible [1].

While the cost of rapid DNA sequencing continues to fall, challenges remain in utilizing this valuable tool to make quick diagnostic decisions. In most clinical settings, the wait for whole-genome sequencing results still runs more than two weeks. Attempts to obtain faster results also have been labor intensive, requiring dedicated teams of experts to sift through the data, one sample at a time.

In the new study, a research team led by Stephen Kingsmore, Rady Children’s Institute for Genomic Medicine, San Diego, CA, describes a streamlined approach that accelerates every step in the process, making it possible to obtain whole-genome test results in a median time of about 20 hours and with much less manual labor. They propose that the system could deliver answers for 30 patients per week using a single genome sequencing instrument.

Here’s how it works: Instead of manually preparing blood samples, his team used special microbeads to isolate DNA much more rapidly with very little labor. The approach reduced the time for sample preparation from 10 hours to less than three. Then, using a state-of-the-art DNA sequencer, they sequence those samples to obtain good quality whole genome data in just 15.5 hours.

The next potentially time-consuming challenge is making sense of all that data. To speed up the analysis, Kingsmore’s team took advantage of a machine-learning system called MOON. The automated platform sifts through all the data using artificial intelligence to search for potentially disease-causing variants.

The researchers paired MOON with a clinical language processing system, which allowed them to extract relevant information from the child’s electronic health records within seconds. Teaming that patient-specific information with data on more than 13,000 known genetic diseases in the scientific literature, the machine-learning system could pick out a likely disease-causing mutation out of 4.5 million potential variants in an impressive 5 minutes or less!

To put the system to the test, the researchers first evaluated its ability to reach a correct diagnosis in a sample of 101 children with 105 previously diagnosed genetic diseases. In nearly every case, the automated diagnosis matched the opinions reached previously via the more lengthy and laborious manual interpretation of experts.

Next, the researchers tested the automated system in assisting diagnosis of seven seriously ill infants in the intensive care unit, and three previously diagnosed infants. They showed that their automated system could reach a diagnosis in less than 20 hours. That’s compared to the fastest manual approach, which typically took about 48 hours. The automated system also required about 90 percent less manpower.

The system nailed a rapid diagnosis for 3 of 7 infants without returning any false-positive results. Those diagnoses were made with an average time savings of more than 22 hours. In each case, the early diagnosis immediately influenced the treatment those children received. That’s key given that, for young children suffering from serious and unexplained symptoms such as seizures, metabolic abnormalities, or immunodeficiencies, time is of the essence.

Of course, artificial intelligence may never replace doctors and other healthcare providers. Kingsmore notes that 106 years after the invention of the autopilot, two pilots are still required to fly a commercial aircraft. Likewise, health care decisions based on genome interpretation also will continue to require the expertise of skilled physicians.

Still, such a rapid automated system will prove incredibly useful. For instance, this system can provide immediate provisional diagnosis, allowing the experts to focus their attention on more difficult unsolved cases or other needs. It may also prove useful in re-evaluating the evidence in the many cases in which manual interpretation by experts fails to provide an answer.

The automated system may also be useful for periodically reanalyzing data in the many cases that remain unsolved. Keeping up with such reanalysis is a particular challenge considering that researchers continue to discover hundreds of disease-associated genes and thousands of variants each and every year. The hope is that in the years ahead, the combination of whole genome sequencing, artificial intelligence, and expert care will make all the difference in the lives of many more seriously ill babies and their families.

Reference:

[1] Diagnosis of genetic diseases in seriously ill children by rapid whole-genome sequencing and automated phenotyping and interpretation. Clark MM, Hildreth A, Batalov S, Ding Y, Chowdhury S, Watkins K, Ellsworth K, Camp B, Kint CI, Yacoubian C, Farnaes L, Bainbridge MN, Beebe C, Braun JJA, Bray M, Carroll J, Cakici JA, Caylor SA, Clarke C, Creed MP, Friedman J, Frith A, Gain R, Gaughran M, George S, Gilmer S, Gleeson J, Gore J, Grunenwald H, Hovey RL, Janes ML, Lin K, McDonagh PD, McBride K, Mulrooney P, Nahas S, Oh D, Oriol A, Puckett L, Rady Z, Reese MG, Ryu J, Salz L, Sanford E, Stewart L, Sweeney N, Tokita M, Van Der Kraan L, White S, Wigby K, Williams B, Wong T, Wright MS, Yamada C, Schols P, Reynders J, Hall K, Dimmock D, Veeraraghavan N, Defay T, Kingsmore SF. Sci Transl Med. 2019 Apr 24;11(489).

Links:

DNA Sequencing Fact Sheet (National Human Genome Research Institute/NIH)

Genomics and Medicine (NHGRI/NIH)

Genetic and Rare Disease Information Center (National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences/NIH)

Stephen Kingsmore (Rady Children’s Institute for Genomic Medicine, San Diego, CA)

NIH Support: National Institute of Child Health and Human Development; National Human Genome Research Institute; National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences

Accelerating Cures in the Genomic Age: The Sickle Cell Example

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Forty-five years ago, when I was a first-year medical student, a lecturer introduced me to a young man with sickle cell disease (SCD). Sickle cell disease is the first “molecular disease”, with its cause having been identified decades ago. That helped me see the connection between the abstract concepts of molecular genetics and their real-world human consequences in a way no textbook could. In fact, it inspired some of my earliest research on human hemoglobin disorders, which I conducted as a postdoctoral fellow.

Today, I’m heartened to report that, thanks to decades of biomedical advances, we stand on the verge of a cure for SCD. While at the American Society of Hematology meeting in San Diego last week, I was excited to be part of a discussion about how the tools and technologies arising from the Human Genome Project are accelerating the quest for cures.

The good news at the meeting included some promising, early results from human clinical trials of SCD gene therapies, including new data from the NIH Clinical Center. Researchers also presented very encouraging pre-clinical work on how gene-editing technologies, such as CRISPR, can be used in ways that may open the door to curing everyone with SCD. In fact, just days before the meeting, the first clinical trial for a CRISPR approach to SCD opened.

One important note: the gene editing research aimed at curing SCD is being done in non-reproductive (somatic) cells. The NIH does not support the use of gene editing technologies in human embryos (germline). I recently reiterated our opposition to germline gene editing, in response to an unethical experiment by a researcher in China who claims to have used CRISPR editing on embryos to produce twin girls resistant to HIV.

SCD affects approximately 100,000 people in the United States, and another 20 million worldwide, mostly in developing nations. This inherited, potentially life-threatening disorder is caused by a specific point mutation in a gene that codes for the beta chain of hemoglobin, a molecule found in red blood cells that deliver oxygen throughout the body. In people with SCD, the mutant hemoglobin forms insoluble aggregates when de-oxygenated. As a result the red cells assume a sickle shape, rather than the usual donut shape. These sickled cells clump together and stick in small blood vessels, resulting in severe pain, blood cell destruction, anemia, stroke, pulmonary hypertension, organ failure, and much too often, early death.

The need for a widespread cure for SCD is great. Since 1998, doctors have used a drug called hydroxyurea to reduce symptoms, but it can cause serious side effects and increase the risk of certain cancers. Blood transfusions can also ease symptoms in certain instances, but they too come with risks and complications. At the present time, the only way to cure SCD is a bone marrow transplant. However, transplants are not an option for many patients due to lack of matched marrow donors.

The good news is that novel genetic approaches have raised hopes of a widespread cure for SCD, possibly even within five to 10 years. So, in September, NIH’s National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute launched the Cure Sickle Cell Initiative to accelerate development of the most promising of these next generation of therapies

At the ASH meeting, that first wave of this progress was evident. A team led by NHLBI’s John Tisdale, in collaboration with Bluebird bio, Cambridge, MA, was among the groups that presented impressive early results from human clinical trials testing novel gene replacement therapies for SCD. In the NIH trial, researchers removed blood precursor cells, called hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs), from a patient’s own bone marrow or bloodstream and used a harmless virus to insert a sickle-resistant hemoglobin gene. Then, after a chemotherapy infusion to condition the patient’s existing bone marrow, they returned the corrected cells to the patient.

So far, nine SCD patients have received the most advanced form of the experimental gene therapy, and Tisdale presented data on those who were farthest out from treatment [1,2]. His team found that in the four patients who were at least six months out, levels of gene therapy-derived hemoglobin were found to equal or exceed their levels of SCD hemoglobin.

Very cool science, but what does this mean for SCD patients’ health and well-being? Well, none of the gene therapy trial participants have required a blood transfusion during the follow-up period. In addition, improvements were seen in their hemoglobin levels and key markers of blood-cell destruction (total bilirubin concentration, lactate dehydrogenase, and reticulocyte counts) compared to baseline. Most importantly, in the years leading up to the clinical trial, all of the participants had experienced frequent painful sickle crises, in which sickled cells blocked their blood vessels. No such episodes were reported among the participants in the months after they received the gene therapy.

Researchers did report that one patient receiving this form of gene therapy developed myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS), a serious condition in which the blood-forming cells in the bone marrow become abnormal. However, there is no indication that the gene replacement technology itself caused the problem, and MDS has previously been linked to the chemotherapy drugs used in conditioning regimens before bone marrow transplants.

The NIH trial is just one of several clinical trials for SCD that are using viral vectors to deliver a variety of genes with therapeutic potential. Other trials actively recruiting are led by researchers at Boston Children’s Hospital, Cincinnati Children’s Hospital, and the University of California, Los Angeles.

While it’s hoped that genes inserted by viral vectors will provide long-lasting or curative treatment, other researchers are betting that new gene-editing technologies, such as CRISPR, will offer the best chance for developing a widespread cure for SCD. One strategy being eyed by these “gene editors” is to correct the SCD mutation, replacing it with a normal gene. Another strategy involves knocking out certain DNA sequences to reactivate production of fetal hemoglobin (HbF).

The HbF protein is produced in the developing fetus to give it better access to oxygen from the mother’s bloodstream. But shortly after birth, the production of fetal hemoglobin shuts down, and the adult form kicks in. Adults normally have very low levels of fetal hemoglobin, which makes sense. However, from genome-wide association studies of human genetic variation, we know that that actual levels of HbF are under genetic control.

A major factor has been mapped to the BCL11A gene, which has subsequently been found to be a master mediator for the fetal to adult hemoglobin switch. Specifically, variations in a red cell specific enhancer of BCL11A affect an adult’s level of HbF— levels of BCL11A protein lead to higher amounts of fetal hemoglobin. Furthermore, it’s been known for some time that rare individuals keep on producing relatively high levels of hemoglobin into adulthood. If people with SCD happen to have a rare mutation that keeps fetal hemoglobin production active in adulthood (the first of these was found as part of my postdoctoral research), their SCD symptoms are much less severe.

Currently, two groups—CRISPR Therapeutics/Vertex Pharmaceuticals and Sangamo Therapeutics/Bioverativ—are gearing up to begin the first U.S. human clinical trials of gene-editing for SCD within the next few months. While they employ different technologies, both approaches involve removing a patient’s HSCs, using gene editing to knock out the BCL11A red cell enhancer, and then returning the gene-edited cells to the patient. The hope is that the gene-edited cells will greatly boost fetal hemoglobin production, thereby offsetting the effects of SCD.

All of this is exciting news for the 100,000 people living in the United States who have SCD. But what about the 300,000 babies born with SCD every year in other parts of the world, mostly in low- and middle-income countries?

The complicated, high-tech procedures that I just described may not be practical for a very long time in places like sub-Saharan Africa. That’s one reason why NIH recently launched a new effort to speed the development of safe, effective genome-editing approaches that could be delivered directly into a patient’s body (in vivo), perhaps by infusion of the CRISPR gene editing apparatus. Recent preclinical experiments demonstrating the promise of in vivo gene editing for Duchenne muscular dystrophy make me optimistic that NIH’s Somatic Cell Genome Editing Program, which is hosting its first gathering of investigators this week, will be able to develop similar approaches for SCD and many other conditions.

While moving forward in this fast-paced field, it is important that we remain ethical, but also remain bold on behalf of the millions of patients with genetic diseases who are still waiting for a cure. We must continue to assess and address the very serious ethical concerns raised by germline gene editing of human embryos, which will irreversibly alter the DNA instruction book of future children and affect future generations. I continue to argue that we are not ready to undertake such experiments.

But the use of gene editing to treat, perhaps even to cure, children and adults with genetic diseases, by correcting the mutation in their relevant tissues (so-called somatic cell gene editing), without risk of passing those changes on to a future generation, holds enormous promise. Somatic cell gene editing is associated with ethical issues that are much more in line with decades of deep thinking about benefits and risks of therapeutic trials.

Finally, we must recognize that somatic cell gene editing is a profoundly promising approach not only for people with SCD, but for all who are struggling with the thousands of diseases that still have no treatments or cures. Real hope for cures has never been greater.

References:

[1] NIH researcher presents encouraging results for gene therapy for severe sickle cell disease. NIH News Release. December 4, 2018

[2] Bluebird bio presents new data for LentiGlobin gene therapy in sickle cell disease at 60th annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology. Bluebird bio. December 3, 2018

Links:

Sickle Cell Disease (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute/NIH)

Cure Sickle Cell Initiative (NHLBI)

John Tisdale (NHLBI)

Somatic Cell Genome Editing Program (Common Fund/NIH)

What are genome editing and CRISPR-Cas9? (National Library of Medicine/NIH)

ClinicalTrials.gov (NIH)

NIH Support: National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; Common Fund

How to Make Biopharmaceuticals Quickly in Small Batches

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Caption: InSCyT system. Image shows (1) production module, (2) purification module, and (3) formulation module.

Credit: Felice Frankel Daniloff, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge

Today, vaccines and other protein-based biologic drugs are typically made in large, dedicated manufacturing facilities. But that doesn’t always fit the need, and it could one day change. A team of researchers has engineered a miniaturized biopharmaceutical “factory” that could fit on a dining room table and produce hundreds to thousands of doses of a needed treatment in about three days.

As published recently in the journal Nature Biotechnology, this on-demand manufacturing system is called Integrated Scalable Cyto-Technology (InSCyT). It is fully automated and can be readily reconfigured to produce virtually any approved or experimental vaccine, hormone, replacement enzyme, antibody, or other biopharmaceutical. With further improvements and testing, InSCyT promises to give researchers and health care providers easy access to specialty biologics needed to treat rare diseases, as well as treatments for combating infectious disease outbreaks in remote towns or villages around the globe.

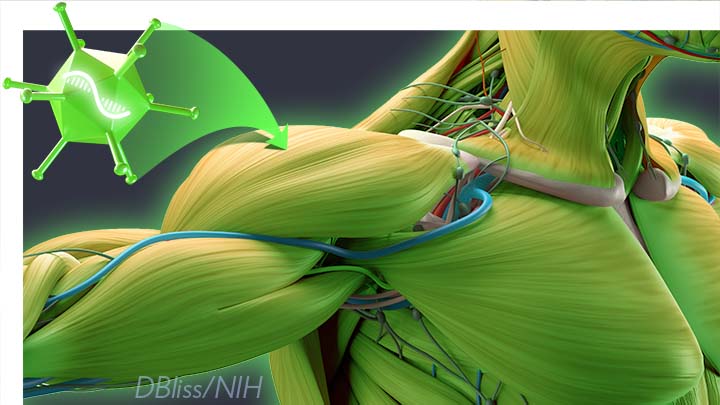

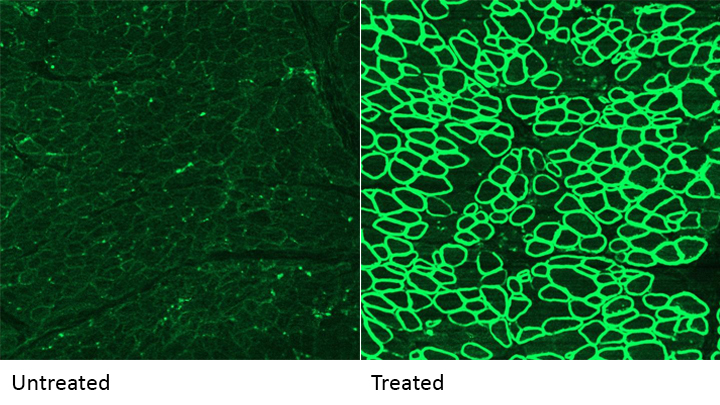

Gene Editing in Dogs Boosts Hope for Kids with Muscular Dystrophy

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Caption: A CRISPR/cas9 gene editing-based treatment restored production of dystrophin proteins (green) in the diaphragm muscles of dogs with Duchenne muscular dystrophy.

Credit: UT Southwestern

CRISPR and other gene editing tools hold great promise for curing a wide range of devastating conditions caused by misspellings in DNA. Among the many looking to gene editing with hope are kids with Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD), an uncommon and tragically fatal genetic disease in which their muscles—including skeletal muscles, the heart, and the main muscle used for breathing—gradually become too weak to function. Such hopes were recently buoyed by a new study that showed infusion of the CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing system could halt disease progression in a dog model of DMD.

As seen in the micrographs above, NIH-funded researchers were able to use the CRISPR/Cas9 editing system to restore production of a critical protein, called dystrophin, by up to 92 percent in the muscle tissue of affected dogs. While more study is needed before clinical trials could begin in humans, this is very exciting news, especially when one considers that boosting dystrophin levels by as little as 15 percent may be enough to provide significant benefit for kids with DMD.

Gene Editing: Gold Nanoparticle Delivery Shows Promise

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

About a month ago, I had the pleasure of welcoming the Juip (pronounced “Yipe”) family from Michigan to NIH. Although you’d never guess it from this photo, two of the Juip’s five children—9-year-old Claire and 11-year-old Jake (both to my left)—have a rare genetic disease called Friedreich’s ataxia (FA). This inherited condition causes progressive damage to their nervous systems and their hearts. No treatment currently exists for kids like Claire and Jake, yet this remarkable family has turned this serious health challenge into an opportunity to raise awareness about the need for biomedical research.

About a month ago, I had the pleasure of welcoming the Juip (pronounced “Yipe”) family from Michigan to NIH. Although you’d never guess it from this photo, two of the Juip’s five children—9-year-old Claire and 11-year-old Jake (both to my left)—have a rare genetic disease called Friedreich’s ataxia (FA). This inherited condition causes progressive damage to their nervous systems and their hearts. No treatment currently exists for kids like Claire and Jake, yet this remarkable family has turned this serious health challenge into an opportunity to raise awareness about the need for biomedical research.

One thing that helps keep the Juips optimistic is the therapeutic potential of CRISPR/Cas9, an innovative gene editing system that may someday make it possible to correct the genetic mutations responsible for FA and many other conditions. So, I’m sure the Juips were among those encouraged by the recent news that NIH-funded researchers have developed a highly versatile approach to CRISPR/Cas9-based therapies. Instead of relying on viruses to carry the gene-editing system into cells, the new approach uses tiny particles of gold as the delivery system!

Next Page