genetic variants

Seeking Consensus on the Use of Population Descriptors in Genomics

Posted on by Eric Green, M.D., Ph.D., National Human Genome Research Institute

Cataloging and characterizing the thousands of genomic variants—differences in DNA sequences among individuals—across human populations is a foundational component of genomics. Scientists from various disciplinary fields compare the variation that occurs within and between the genomes of individuals and groups. Such efforts include attributing descriptors to population groups, which have historically included the use of social constructs such as race, ethnicity, ancestry, and political geographic location. Like any descriptors, these words do not fully account for the scope and diversity of the human species.

The use of race, ethnicity, and ancestry as descriptors of population groups in biomedical and genomics research has been a topic of consistent and rigorous debate within the scientific community. Human health, disease, and ancestry are all tied to how we define and explain human diversity. For centuries, scientists have incorrectly inferred that people of different races reflect discrete biological groups, which has led to deep-rooted health inequities and reinforced scientific racism.

In recent decades, genomics research has revealed the complexity of human genomic variation and the limitations of these socially derived population descriptors. The scientific community has long worked to move beyond the use of the social construct of race as a population descriptor and provide guidance about agreed-upon descriptors of human populations. Such a need has escalated with the growing numbers of large population-scale genomics studies being launched around the world, including in the United States.

To answer this call, NIH is sponsoring a National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM) study that aims to develop best practices in the use of race, ethnicity, and genetic ancestry in genomics research. The NASEM study is sponsored by 14 NIH institutes, centers, offices, and programs, and the resulting report will be released in February 2023.

Experts from various fields—including genomics, medicine, and social sciences—are conducting the study. Much of the effort will revolve around reviewing and assessing existing methodologies, benefits, and challenges in the use of race and ethnicity and other population descriptors in genomics research. The ad hoc committee will host three public meetings to obtain input. Look for more information regarding the committee’s next public session planned for April 2022 on the NASEM “Race, Ethnicity, and Ancestry as Population Descriptors in Genomics Research” website.

To further underscore the need for the NASEM study, an NIH study published in December 2021 revealed that the descriptors for human populations used in the genetics literature have evolved over the last 70 years [1]. For example, the use of the word “race” has substantially decreased, while the uses of “ancestry” and “ethnicity” have increased. The study provided additional evidence that population descriptors often reflect fluid, social constructs whose intention is to describe groups with common genetic ancestry. These findings reinforce the timeliness of the NASEM study, with the clear need for experts to provide guidance for establishing more stable and meaningful population descriptors for use in future genomics studies.

The full promise of genomics, including its application to medicine, depends on improving how we explain human genomic variation. The words that we use to describe participants in research studies and populations must be transparent, thoughtful, and consistent—in addition to avoiding the perpetuation of structural racism. The best and most fruitful genomics research demands a better approach.

Reference:

[1] Evolving use of ancestry, ethnicity, and race in genetics research—A survey spanning seven decades. Byeon YJJ, Islamaj R, Yeganova L, Wilbur WJ, Lu Z, Brody LC, Bonham VL. Am J Hum Genet. 2021 Dec 2;108(12):2215-2223.

Links:

Use of Race, Ethnicity, and Ancestry as Population Descriptors in Genomics Research (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine)

“Language used by researchers to describe human populations has evolved over the last 70 years.” (National Human Genome Research Institute/NIH)

Genomic Variation Program (NHGRI)

[Note: Acting NIH Director Lawrence Tabak has asked the heads of NIH’s institutes and centers to contribute occasional guest posts to the blog as a way to highlight some of the cool science that they support and conduct. This is the third in the series of NIH institute and center guest posts that will run until a new permanent NIH director is in place.]

Gene-Editing Advance Puts More Gene-Based Cures Within Reach

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

There’s been tremendous excitement recently about the potential of CRISPR and related gene-editing technologies for treating or even curing sickle cell disease (SCD), muscular dystrophy, HIV, and a wide range of other devastating conditions. Now comes word of another remarkable advance—called “prime editing”—that may bring us even closer to reaching that goal.

As groundbreaking as CRISPR/Cas9 has been for editing specific genes, the system has its limitations. The initial version is best suited for making a double-stranded break in DNA, followed by error-prone repair. The outcome is generally to knock out the target. That’s great if eliminating the target is the desired goal. But what if the goal is to fix a mutation by editing it back to the normal sequence?

The new prime editing system, which was described recently by NIH-funded researchers in the journal Nature, is revolutionary because it offers much greater control for making a wide range of precisely targeted edits to the DNA code, which consists of the four “letters” (actually chemical bases) A, C, G, and T [1].

Already, in tests involving human cells grown in the lab, the researchers have used prime editing to correct genetic mutations that cause two inherited diseases: SCD, a painful, life-threatening blood disorder, and Tay-Sachs disease, a fatal neurological disorder. What’s more, they say the versatility of their new gene-editing system means it can, in principle, correct about 89 percent of the more than 75,000 known genetic variants associated with human diseases.

In standard CRISPR, a scissor-like enzyme called Cas9 is used to cut all the way through both strands of the DNA molecule’s double helix. That usually results in the cell’s DNA repair apparatus inserting or deleting DNA letters at the site. As a result, CRISPR is extremely useful for disrupting genes and inserting or removing large DNA segments. However, it is difficult to use this system to make more subtle corrections to DNA, such as swapping a letter T for an A.

To expand the gene-editing toolbox, a research team led by David R. Liu, Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard, Cambridge, MA, previously developed a class of editing agents called base editors [2,3]. Instead of cutting DNA, base editors directly convert one DNA letter to another. However, base editing has limitations, too. It works well for correcting four of the most common single letter mutations in DNA. But at least so far, base editors haven’t been able to make eight other single letter changes, or fix extra or missing DNA letters.

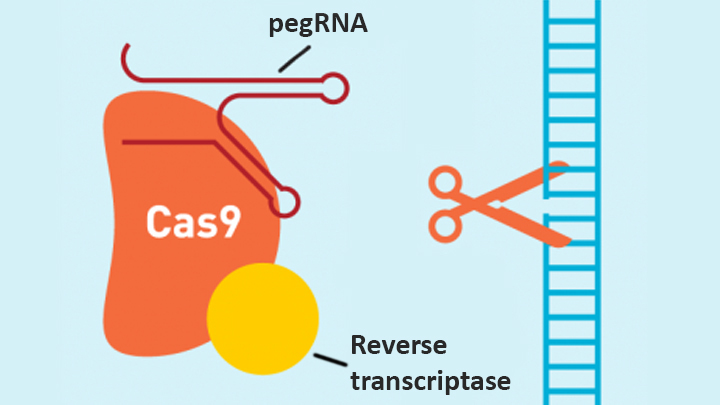

In contrast, the new prime editing system can precisely and efficiently swap any single letter of DNA for any other, and can make both deletions and insertions, at least up to a certain size. The system consists of a modified version of the Cas9 enzyme fused with another enzyme, called reverse transcriptase, and a specially engineered guide RNA, called pegRNA. The latter contains the desired gene edit and steers the needed editing apparatus to a specific site in a cell’s DNA.

Once at the site, the Cas9 nicks one strand of the double helix. Then, reverse transcriptase uses one DNA strand to “prime,” or initiate, the letter-by-letter transfer of new genetic information encoded in the pegRNA into the nicked spot, much like the search-and-replace function of word processing software. The process is then wrapped up when the prime editing system prompts the cell to remake the other DNA strand to match the new genetic information.

So far, in tests involving human cells grown in a lab dish, Liu and his colleagues have used prime editing to correct the most common mutation that causes SCD, converting a T to an A. They were also able to remove four DNA letters to correct the most common mutation underlying Tay-Sachs disease, a devastating condition that typically produces symptoms in children within the first year and leads to death by age four. The researchers also used their new system to insert new DNA segments up to 44 letters long and to remove segments at least 80 letters long.

Prime editing does have certain limitations. For example, 11 percent of known disease-causing variants result from changes in the number of gene copies, and it’s unclear if prime editing can insert or remove DNA that’s the size of full-length genes—which may contain up to 2.4 million letters.

It’s also worth noting that now-standard CRISPR editing and base editors have been tested far more thoroughly than prime editing in many different kinds of cells and animal models. These earlier editing technologies also may be more efficient for some purposes, so they will likely continue to play unique and useful roles in biomedicine.

As for prime editing, additional research is needed before we can consider launching human clinical trials. Among the areas that must be explored are this technology’s safety and efficacy in a wide range of cell types, and its potential for precisely and safely editing genes in targeted tissues within living animals and people.

Meanwhile, building on all these bold advances, efforts are already underway to accelerate the development of affordable, accessible gene-based cures for SCD and HIV on a global scale. Just last month, NIH and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation announced a collaboration that will invest at least $200 million over the next four years toward this goal. Last week, I had the chance to present this plan and discuss it with global health experts at the Grand Challenges meeting Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. The project is an unprecedented partnership designed to meet an unprecedented opportunity to address health conditions that once seemed out of reach but—as this new work helps to show—may now be within our grasp.

References:

[1] Search-and-replace genome editing without double-strand breaks or donor DNA. Anzalone AV, Randolph PB, Davis JR, Sousa AA, Koblan LW, Levy JM, Chen PJ, Wilson C, Newby GA, Raguram A, Liu DR. Nature. Online 2019 October 21. [Epub ahead of print]

[2] Programmable editing of a target base in genomic DNA without double-stranded DNA cleavage. Komor AC, Kim YB, Packer MS, Zuris JA, Liu DR. Nature. 2016 May 19;533(7603):420-424.

[3] Programmable base editing of A•T to G•C in genomic DNA without DNA cleavage. Gaudelli NM, Komor AC, Rees HA, Packer MS, Badran AH, Bryson DI, Liu DR. Nature. 2017 Nov 23;551(7681):464-471.

Links:

Tay-Sachs Disease (Genetics Home Reference/National Library of Medicine/NIH)

Sickle Cell Disease (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute/NIH)

Cure Sickle Cell Initiative (NHLBI)

What are Genome Editing and CRISPR-Cas9? (National Library of Medicine/NIH)

Somatic Cell Genome Editing Program (Common Fund/NIH)

David R. Liu (Harvard, Cambridge, MA)

NIH Support: National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases; National Human Genome Research Institute; National Institute for General Medical Sciences; National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering; National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences

A New Piece of the Alzheimer’s Puzzle

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Credit: National Institute on Aging, NIH

For the past few decades, researchers have been busy uncovering genetic variants associated with an increased risk of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) [1]. But there’s still a lot to learn about the many biological mechanisms that underlie this devastating neurological condition that affects as many as 5 million Americans [2].

As an example, an NIH-funded research team recently found that AD susceptibility may hinge not only upon which gene variants are present in a person’s DNA, but also how RNA messages encoded by the affected genes are altered to produce proteins [3]. After studying brain tissue from more than 450 deceased older people, the researchers found that samples from those with AD contained many more unusual RNA messages than those without AD.

Big Data Study Reveals Possible Subtypes of Type 2 Diabetes

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Caption: Computational model showing study participants with type 2 diabetes grouped into three subtypes, based on similarities in data contained in their electronic health records. Such information included age, gender (red/orange/yellow indicates females; blue/green, males), health history, and a range of routine laboratory and medical tests.

Credit: Dudley Lab, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York

In recent years, there’s been a lot of talk about how “Big Data” stands to revolutionize biomedical research. Indeed, we’ve already gained many new insights into health and disease thanks to the power of new technologies to generate astonishing amounts of molecular data—DNA sequences, epigenetic marks, and metabolic signatures, to name a few. But what’s often overlooked is the value of combining all that with a more mundane type of Big Data: the vast trove of clinical information contained in electronic health records (EHRs).

In a recent study in Science Translational Medicine [1], NIH-funded researchers demonstrated the tremendous potential of using EHRs, combined with genome-wide analysis, to learn more about a common, chronic disease—type 2 diabetes. Sifting through the EHR and genomic data of more than 11,000 volunteers, the researchers uncovered what appear to be three distinct subtypes of type 2 diabetes. Not only does this work have implications for efforts to reduce this leading cause of death and disability, it provides a sneak peek at the kind of discoveries that will be made possible by the new Precision Medicine Initiative’s national research cohort, which will enroll 1 million or more volunteers who agree to share their EHRs and genomic information.

Precision Medicine: Who Benefits from Aspirin to Prevent Colorectal Cancer?

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

In recent years, scientific evidence has begun to accumulate that indicates taking aspirin or other non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) on a daily basis may lower the risk of developing colorectal cancer. Now, a new study provides more precise information on who might benefit from this particular prevention strategy, as well as who might not.

In recent years, scientific evidence has begun to accumulate that indicates taking aspirin or other non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) on a daily basis may lower the risk of developing colorectal cancer. Now, a new study provides more precise information on who might benefit from this particular prevention strategy, as well as who might not.

Published in the journal JAMA, the latest work shows that, for the majority of people studied, regular use of aspirin or NSAIDs was associated with about a one-third lower risk of developing colorectal cancer. But the international research team, partly funded by NIH, also found that not all regular users of aspirin/NSAIDs reaped such benefits—about 9 percent experienced no reduction in colorectal cancer risk and 4 percent actually appeared to have an increased risk [1]. Was this just coincidence, or might there be a biological explanation?

Autism Architecture: Unrolling the Genetic Blueprint

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

We know that a combination of genetic and environmental factors influence a child’s risk of autism spectrum disorder (ASD), which is a diverse group of developmental brain conditions that disrupt language, communication, and social interaction. Still, there remain a great many unknowns, including the crucial issues of what proportion of ASD risk is due to genes and what sorts of genes are involved. Answering such questions may hold the key to expanding our understanding of the disorder—and thereby to devising better ways to help the millions of Americans whose lives are touched by ASD [1].

We know that a combination of genetic and environmental factors influence a child’s risk of autism spectrum disorder (ASD), which is a diverse group of developmental brain conditions that disrupt language, communication, and social interaction. Still, there remain a great many unknowns, including the crucial issues of what proportion of ASD risk is due to genes and what sorts of genes are involved. Answering such questions may hold the key to expanding our understanding of the disorder—and thereby to devising better ways to help the millions of Americans whose lives are touched by ASD [1].

Last year, I shared how NIH-funded researchers had identified rare, spontaneous genetic mutations that appear to play a role in causing ASD. Now, there’s additional news to report. In the largest study of its kind to date, an international team supported by NIH recently discovered that common, inherited genetic variants, acting in tandem with each other or with rarer variants, can also set the stage for ASD—accounting for nearly half of the risk for what’s called “strictly defined autism,” the full-blown manifestation of the disorder. And, when the effects of both rare and common genetic variants are tallied up, we can now trace about 50 to 60 percent of the risk of strictly defined autism to genetic factors.